The American Airlines Bankruptcy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Outreach

Truckee Tahoe Airport District COMMUNITY OUTREACH Neighborhood Meetings October 2016 Draft Acknowledgements We wish to thank our supportive community who provided their insight and thoughtful feedback. TRUCKEE TAHOE AIRPORT DISTRICT BOARD AIRPORT COMMUNITY ADVISORY TEAM Lisa Wallace, President Kathryn Rohlf, Community Member/Chair James W. Morrison, Vice President Joe Polverari, Pilot Member/Vice Chair Mary Hetherington Christopher Gage, Pilot Member John B. Jones, Jr. Leigh Golden, Pilot Member J. Thomas Van Berkem Kent Hoopingarner, Community Member/Treasurer Lisa Krueger, Community Member AIRPORT STAFF Kevin Smith, General Manager BRIDGENET INTERNATIONAL Hardy Bullock, Director of Aviation Cindy Gibbs, Airspace Study Project Manager and Community Services Marc R. Lamb, Aviation and FRESHTRACKS COMMUNICATIONS Community Services Manager Seana Doherty, Owner/Founder Michael Cooke, Aviation and Phebe Bell, Facilitator Community Services Manager Amanda Wiebush, Associate Jill McClendon, Aviation and Community Greyson Howard,Mead &Associate Hunt, Inc. M & H Architecture, Inc. Services Program Coordinator 133 Aviation Boulevard, Suite 100 Lauren C. Tapia, District Clerk MEAD & HUNT,Santa INC. Rosa, California 95403 Mitchell Hooper,707-526-5010 West Coast Aviation meadhunt.com Planning Manager Brad Musinski, Aviation Planner Maranda Thompson, Aviation Planner TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND PROGRAM DESIGN .............................................. 1 2 NEIGHBORHOOD FEEDBACK ..................................................................... 5 APPENDICES A. Meeting Materials B. Public Comments C. Advertising and Marketing Efforts Introduction and ProgramMead & Hunt, Inc. Design M & H Architecture, Inc. 133 Aviation Boulevard, Suite 100 Santa Rosa, California 95403 707-526-5010 meadhunt.com INTRODUCTION Purpose The Truckee Tahoe Airport District (TTAD) understands that community input is incredibly valuable in developing good policies and making sound decisions about Truckee Tahoe Airport (TRK). -

AMR Corporation

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For fiscal year ended December 31, 2004. o Transition Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Commission file number 1-8400. AMR Corporation (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 75-1825172 (State or other jurisdiction (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) of incorporation or organization) 4333 Amon Carter Blvd. Fort Worth, Texas 76155 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code (817) 963-1234 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of exchange on which registered Common stock, $1 par value per share New York Stock Exchange 9.00% Debentures due 2016 New York Stock Exchange 7.875% Public Income Notes due 2039 New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: NONE (Title of Class) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes No o. Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K (§ 229.405 of this chapter) is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of the registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. -

United States Court of Appeals for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

USCA Case #11-1018 Document #1351383 Filed: 01/06/2012 Page 1 of 12 United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT Argued November 8, 2011 Decided January 6, 2012 No. 11-1018 REPUBLIC AIRLINE INC., PETITIONER v. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, RESPONDENT On Petition for Review of an Order of the Department of Transportation Christopher T. Handman argued the cause for the petitioner. Robert E. Cohn, Patrick R. Rizzi and Dominic F. Perella were on brief. Timothy H. Goodman, Senior Trial Attorney, United States Department of Transportation, argued the cause for the respondent. Robert B. Nicholson and Finnuala K. Tessier, Attorneys, United States Department of Justice, Paul M. Geier, Assistant General Counsel for Litigation, and Peter J. Plocki, Deputy Assistant General Counsel for Litigation, were on brief. Joy Park, Trial Attorney, United States Department of Transportation, entered an appearance. USCA Case #11-1018 Document #1351383 Filed: 01/06/2012 Page 2 of 12 2 Before: HENDERSON, Circuit Judge, and WILLIAMS and RANDOLPH, Senior Circuit Judges. Opinion for the Court filed by Circuit Judge HENDERSON. KAREN LECRAFT HENDERSON, Circuit Judge: Republic Airline Inc. (Republic) challenges an order of the Department of Transportation (DOT) withdrawing two Republic “slot exemptions” at Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (Reagan National) and reallocating those exemptions to Sun Country Airlines (Sun Country). In both an informal letter to Republic dated November 25, 2009 and its final order, DOT held that Republic’s parent company, Republic Airways Holdings, Inc. (Republic Holdings), engaged in an impermissible slot-exemption transfer with Midwest Airlines, Inc. (Midwest). -

July/August 2000 Volume 26, No

Irfc/I0 vfa£ /1 \ 4* Limited Edition Collectables/Role Model Calendars at home or in the office - these photo montages make a statement about who we are and what we can be... 2000 1999 Cmdr. Patricia L. Beckman Willa Brown Marcia Buckingham Jerrie Cobb Lt. Col. Eileen M. Collins Amelia Earhart Wally Funk julie Mikula Maj. lacquelyn S. Parker Harriet Quimby Bobbi Trout Captain Emily Howell Warner Lt. Col. Betty Jane Williams, Ret. 2000 Barbara McConnell Barrett Colonel Eileen M. Collins Jacqueline "lackie" Cochran Vicky Doering Anne Morrow Lindbergh Elizabeth Matarese Col. Sally D. Woolfolk Murphy Terry London Rinehart Jacqueline L. “lacque" Smith Patty Wagstaff Florene Miller Watson Fay Cillis Wells While They Last! Ship to: QUANTITY Name _ Women in Aviation 1999 ($12.50 each) ___________ Address Women in Aviation 2000 $12.50 each) ___________ Tax (CA Residents add 8.25%) ___________ Shipping/Handling ($4 each) ___________ City ________________________________________________ T O TA L ___________ S ta te ___________________________________________ Zip Make Checks Payable to: Aviation Archives Phone _______________________________Email_______ 2464 El Camino Real, #99, Santa Clara, CA 95051 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS (ISSN 0273-608X) 99 NEWS INTERNATIONAL Published by THE NINETV-NINES* INC. International Organization of Women Pilots A Delaware Nonprofit Corporation Organized November 2, 1929 WOMEN PILOTS INTERNATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Box 965, 7100 Terminal Drive OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OFTHE NINETY-NINES® INC. Oklahoma City, -

Adaptive Connected.Xlsx

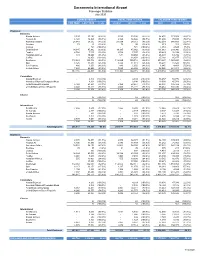

Sacramento International Airport Passenger Statistics July 2020 CURRENT MONTH FISCAL YEAR TO DATE CALENDAR YEAR TO DATE THIS YEAR LAST YEAR % +/(-) 2020/21 2019/20 % +/(-) 2020 2019 % +/(-) Enplaned Domestic Alaska Airlines 3,593 33,186 (89.2%) 3,593 33,186 (89.2%) 54,432 173,858 (68.7%) Horizon Air 6,120 14,826 (58.7%) 6,120 14,826 (58.7%) 31,298 75,723 (58.7%) American Airlines 28,089 54,512 (48.5%) 28,089 54,512 (48.5%) 162,319 348,689 (53.4%) Boutique 79 95 (16.8%) 79 95 (16.8%) 613 201 205.0% Contour - 721 (100.0%) - 721 (100.0%) 4,461 2,528 76.5% Delta Airlines 14,185 45,962 (69.1%) 14,185 45,962 (69.1%) 111,063 233,946 (52.5%) Frontier 4,768 7,107 (32.9%) 4,768 7,107 (32.9%) 25,423 38,194 (33.4%) Hawaiian Airlines 531 10,660 (95.0%) 531 10,660 (95.0%) 26,393 64,786 (59.3%) Jet Blue - 16,858 (100.0%) - 16,858 (100.0%) 25,168 85,877 (70.7%) Southwest 112,869 300,716 (62.5%) 112,869 300,716 (62.5%) 899,647 1,963,253 (54.2%) Spirit 8,425 11,318 (25.6%) 8,425 11,318 (25.6%) 38,294 15,526 146.6% Sun Country 886 1,650 (46.3%) 886 1,650 (46.3%) 1,945 4,401 (55.8%) United Airlines 7,620 46,405 (83.6%) 7,620 46,405 (83.6%) 98,028 281,911 (65.2%) 187,165 544,016 (65.6%) 187,165 544,016 (65.6%) 1,479,084 3,288,893 (55.0%) Commuters Alaska/Skywest - 4,304 (100.0%) - 4,304 (100.0%) 36,457 50,776 (28.2%) American/Skywest/Compass/Mesa - 8,198 (100.0%) - 8,198 (100.0%) 18,030 45,781 (60.6%) Delta/Skywest/Compass 5,168 23,651 (78.1%) 5,168 23,651 (78.1%) 62,894 146,422 (57.0%) United/Skywest/GoJet/Republic 4,040 16,221 (75.1%) 4,040 16,221 (75.1%) -

(KCM) As It Has Moved to a Permanent Program of the TSA

We are very surprised at the company’s announcement that they may be considering to opt out of Known Crewmember (KCM) as it has moved to a permanent program of the TSA. The idea behind KCM is not simply to expedite security screening for known assets, such as pilots, but to alleviate additional TSA security resources in order to have more effect at passenger screening portals. This makes our entire U.S. travel system safer and protects us from additional threats. In a message to the crew force, the company writes, “The KCM program was halted abruptly as a trial offering and has suddenly become an ongoing commercial program with considerable fees attached to it. Given the extremely short notice we were given and the extensive fees, we are only now able to begin to assess the details and determine our options, and how we might reach a reasonable ongoing arrangement with the KCM program administrators.” Last year, KCM began issuing barcodes to expedite screening, if your airline paid for it. However, FedEx chose not to subscribe to the optional barcodes. Airlines for America (A4A) was notified of KCM moving to a permanent program months ago. There was nothing abrupt about the halting of the test program as the date was solidified and reported long ago. Not only has this now become a permanent program and industry best practice, FedEx and UPS are the only two carriers reported thus far to have “carved themselves out” of the 43 total US airlines participating. As we all know, another successful terror act against aviation will not “carve” FedEx out, but affect all airlines with disastrous operational and financial impacts equally. -

Air Travel Consumer Report

Air Travel Consumer Report A Product Of THE OFFICE OF AVIATION CONSUMER PROTECTION Issued: August 2021 Flight Delays1 June 2021 January - June 2021 Mishandled Baggage, Wheelchairs, and Scooters 1 June 2021 January -June 2021 Oversales1 2nd Quarter 2021 Consumer Complaints2 June 2021 (Includes Disability and January - June 2021 Discrimination Complaints) Airline Animal Incident Reports4 June 2021 Customer Service Reports to 3 the Dept. of Homeland Security June 2021 1 Data collected by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Website: http://www.bts.gov 2 Data compiled by the Office of Aviation Consumer Protection. Website: http://www.transportation.gov/airconsumer 3 Data provided by the Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration 4 Data collected by the Office of Aviation Consumer Protection. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page Section Page Flight Delays Flight Delays (continued) Introduction 3 Table 8 35 Explanation 4 List of Regularly Scheduled Domestic Flights with Tarmac Delays Over 3 Hours, By Marketing/Operating Carrier Branded Codeshare Partners 5 Table 8A Table 1 6 List of Regularly Scheduled International Flights with 36 Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Tarmac Delays Over 4 Hours, By Marketing/Operating Carrier Operations Arriving On-Time, by Reporting Marketing Carrier Appendix 37 Table 1A 7 Mishandled Baggage Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Ranking- by Marketing Carrier (Monthly) 39 Operations Arriving On-Time, by Reporting Operating Carrier Ranking- by Marketing Carrier (YTD) 40 Table 1B 8 -

Poverty Pay and Food Stamps at American Airlines Survey of Passenger Service Agents at American-Owned Envoy Air Reveals Reliance on Public Assistance Programs

Poverty Pay and Food Stamps at American Airlines Survey of passenger service agents at American-owned Envoy Air reveals reliance on public assistance programs Poverty Pay and Food Stamps at American Airlines Survey of passenger service agents at American-owned Envoy Air reveals reliance on public assistance programs Executive summary Envoy Air is a wholly-owned subsidiary of American Airlines, the largest passenger airline in the United States. Envoy employs more than 3,800 passenger service agents whose responsibilities range from guiding planes on the tarmac to de-escalating tense situations among customers. Envoy agents work at some of the nation’s biggest and busiest airports as well as smaller regional airports that connect flyers to travel destinations around the country. Wages for Envoy agents are among the lowest in the airline industry and start as low as $9.48 an hour. Many agents say they must rely on public assistance programs because of the low pay. This report explores the use of public assistance and the effects of low wages among Envoy passenger service agents, drawing on data from a survey of 900 employees across the country, as well as first-hand accounts of their experiences. The online survey was conducted by the agents’ union, the Communications Workers of America (CWA). Approximately one quarter of all Envoy agents participated. The survey’s major findings include: » Twenty-seven percent of survey participants reported relying on public assistance to meet the needs of their household » Food stamps were reported as the most commonly- used type of public assistance (20 percent of all survey participants) The Communications Workers of America (CWA) represents 700,000 » Among agents not receiving public assistance, 82 percent workers in private and public sector of respondents said they rely on help from family and employment in the United States, friends, often in the form of financial assistance, childcare Canada and Puerto Rico. -

Lit 2017 Cafr.Pdf

COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT BILL AND HILLARY CLINTON NATIONAL AIRPORT A COMPONENT UNIT OF THE CITY OF LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS FOR THE FISCAL YEARS ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2017 AND 2016 Prepared by: Bill and Hillary Clinton National Airport Finance Department TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT INTRODUCTORY SECTION 5 INTRODUCTORY SECTION INTRODUCTORY SECTION CONTENTS: State Airport Locations and LIT Service Area Little Rock Municipal Airport Commission Organizational Structure Airport Executive Leadership Letter of Transmittal to the Airport Commission Certificate of Achievement for Excellence in Financial Reporting 6 COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT INTRODUCTORY SECTION STATE AIRPORT LOCATIONS AND LIT SERVICE AREA XNA Rogers HRO LIT Secondary Springdale Catchment Area Fayetteville JBO LIT Primary Catchment Area Memphis FSM Conway Little Rock North Little Rock LIT HOT Pine Bluff Texarkana TEX ELD Greenville COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 7 INTRODUCTORY SECTION INTENTIONALLY BLANK 8 COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT INTRODUCTORY SECTION LITTLE ROCK MUNICIPAL AIRPORT COMMISSION STACY HURST JESSE MASON GUS VRATSINAS Chairwoman Vice Chair/Treasurer Secretary JOHN RUTLEDGE MEREDITH CATLETT JILL FLOYD MARK CAMP Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 9 COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 9 INTRODUCTORY SECTION ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DEPUTY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DIRECTOR PUBLIC -

US and Plaintiff States V. US Airways Group, Inc. and AMR Corporation

Case 1:13-cv-01236-CKK Document 170 Filed 04/25/14 Page 1 of 28 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al. Plaintiffs, v. Case No. 1:13-cv-01236 (CKK) US AIRWAYS GROUP, INC. and AMR CORPORATION Defendants. FINAL JUDGMENT WHEREAS, Plaintiffs United States of America ("United States") and the States of Arizona, Florida, Tennessee and Michigan, the Commonwealths of Pennsylvania and Virginia, and the District of Columbia ("Plaintiff States") filed their Complaint against Defendants US Airways Group, Inc. ("US Airways") and AMR Corporation ("American") on August 13, 2013, as amended on September 5, 2013; AND WHEREAS, the United States and the Plaintiff States and Defendants, by their respective attorneys, have consented to the entry of this Final Judgment without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and without this Final Judgment constituting any evidence against or admission by any party regarding any issue of fact or law; AND WHEREAS, Defendants agree to be bound by the provisions of the Final Judgment pending its approval by the Court; 1 Case 1:13-cv-01236-CKK Document 170 Filed 04/25/14 Page 2 of 28 AND WHEREAS, the essence of this Final Judgment is the prompt and certain divestiture of certain rights or assets by the Defendants to assure that competition is not substantially lessened; AND WHEREAS, the Final Judgment requires Defendants to make certain divestitures for the purposes of remedying the loss of competition alleged in the Complaint; AND WHEREAS, Defendants have represented to the United States and the Plaintiff States that the divestitures required below can and will be made, and that the Defendants will later raise no claim of hardship or difficulty as grounds for asking the Court to modify any of the provisions below; NOW THEREFORE, before any testimony is taken, without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and upon consent of the parties, it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED, AND DECREED: I. -

Columbus Regional Airport Authority

COLUMBUS REGIONAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY - PORT COLUMBUS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TRAFFIC REPORT June 2014 7/22/2014 Airline Enplaned Passengers Deplaned Passengers Enplaned Air Mail Deplaned Air Mail Enplaned Air Freight Deplaned Air Freight Landings Landed Weight Air Canada Express - Regional 2,377 2,278 - - - - 81 2,745,900 Air Canada Express Totals 2,377 2,278 - - - - 81 2,745,900 AirTran 5,506 4,759 - - - - 59 6,136,000 AirTran Totals 5,506 4,759 - - - - 59 6,136,000 American 21,754 22,200 - - - 306 174 22,210,000 Envoy Air** 22,559 22,530 - - 2 ,027 2 ,873 527 27,043,010 American Totals 44,313 44,730 - - 2,027 3,179 701 49,253,010 Delta 38,216 36,970 29,594 34,196 25,984 36,845 278 38,899,500 Delta Connection - ExpressJet 2,888 2,292 - - - - 55 3,709,300 Delta Connection - Chautauqua 15,614 14,959 - - 640 - 374 15,913,326 Delta Connection - Endeavor 4 ,777 4,943 - - - - 96 5,776,500 Delta Connection - GoJet 874 748 - - 33 - 21 1,407,000 Delta Connection - Shuttle America 6,440 7,877 - - 367 - 143 10,536,277 Delta Connection - SkyWest 198 142 - - - - 4 188,000 Delta Totals 69,007 67,931 29,594 34,196 27,024 36,845 971 76,429,903 Southwest 97,554 96,784 218,777 315,938 830 103,146,000 Southwest Totals 97,554 96,784 - - 218,777 315,938 830 103,146,000 United 3 ,411 3,370 13,718 6 ,423 1 ,294 8 ,738 30 3,990,274 United Express - ExpressJet 13,185 13,319 - - - - 303 13,256,765 United Express - Mesa 27 32 - - - - 1 67,000 United Express - Republic 4,790 5,133 - - - - 88 5,456,000 United Express - Shuttle America 9,825 9,076 - - - - 151 10,919,112 -

FOOD SAFETY in AVIATION Presented by Brig Gen(Retd) Md Abdur Rab Miah

WELCOME TO CAA, BANGLADESH DECRALATION OF WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY In 1974, the 27th world health Assembly stressed, “ the need for each member state to shoulder the responsibilities for the Safety of food Wat e r , and proper handling of waste disposal in international traffic.” FOOD SAFETY IN AVIATION Presented by Brig Gen(Retd) Md Abdur Rab Miah CAPSCA Focal Person & Aviation Public Health Inspector and consultant Civil Aviation Authority, Bangladesh POINTS OF DISCUSSION Introduction Standards of Flight catering Premises Water Supply Storage of Food Food Handlers Food Preparation Staff Cloakroom Crew Meals Transportation of food to the aircraft Waste Disposal Flight Catering Laboratory Flight Catering Inspection , Conclusion INTRODUCTION Food safety in Aviation ensures hygiene, wholesomeness and soundness of food from its production to its final consumption by the passengers and crew. So, the air operators are to provide contaminants free ,hygienic , safe, attractive, palatable and high quality food to the consumers. Because the passengers assess an airline by the quality of the meals it serves on board. STANDARD OF FLT CAT PREMISES 1) Flight catering premises - spacious (2) Protection against rodents & insects 3) Lighting and ventilation (4) Located at or in the vicinity of airport 5) No projections or ledges on the wall (6) Floor- smooth but not slippery (7) Walls to be tiles fitted with min partition (8) or, Washable/Glossy paint PROTECTION AGAINST INSECTS & RODENTS All doors, windows and other openings should be insect-proof • Plastic insect-proof screening is recommended Kitchen entrances should have self-closing, double doors, opening outwards. EXCLUSION OF DOMESTIC ANIMALS Dogs, cats and other domestic animals should be excluded from all parts of the food premises.