"Blessing" of Atomic Energy in the Early Cold War Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is War Necessary for Economic Growth?

Historically Speaking-Issues (merged papers) 09/26/06 IS WAR NECESSARY FOR ECONOMIC GROWTH? VERNON W. RUTTAN UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA CLEMONS LECTURE SAINT JOHNS UNIVERSITY COLLEGEVILLE, MINNESOTA OCTOBER 9, 2006 1 OUTLINE PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION 4 SIX GENERAL PURPOSE TECHNOLOGIES 5 The Aircraft Industry 6 Nuclear Power 7 The Computer Industry 9 The Semiconductor Industry 11 The Internet 13 The Space Industries 15 TECHNOLOGICAL MATURITY 17 IS WAR NECESSARY? 20 Changes in Military Doctrine 20 Private Sector Entrepreneurship 23 Public Commercial Technology Development 24 ANTICIPATING TECHNOLOGICAL FUTURES 25 PERSPECTIVES 28 SELECTED REFERENCES 32 2 PREFACE In a book published in 2001, Technology, Growth and Development: An Induced Innovation Perspective, I discussed several examples but did not give particular attention to the role of military and defense related research, development and procurement as a source of commercial technology development. A major generalization from that work was that government had played an important role in the development of almost every general purpose technology in which the United States was internationally competitive. Preparation for several speaking engagements following the publication of the book led to a reexamination of what I had written. It became clear to me that defense and defense related institutions had played a predominant role in the development of many of the general purpose technologies that I had discussed. The role of military and defense related research, development and procurement was sitting there in plain sight. But I was unable or unwilling to recognize it! It was with considerable reluctance that I decided to undertake the preparation of the book I discuss in this paper, Is War Necessary for Economic Growth? Military Procurement and Technology Development. -

Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. Atoms

ATOMS PEACE WAR Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission Richard G. Hewlett and lack M. Roll With a Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall and an Essay on Sources by Roger M. Anders University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Published 1989 by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission; work made for hire. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewlett, Richard G. Atoms for peace and war, 1953-1961. (California studies in the history of science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Nuclear energy—United States—History. 2. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—History. 3. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890-1969. 4. United States—Politics and government-1953-1961. I. Holl, Jack M. II. Title. III. Series. QC792. 7. H48 1989 333.79'24'0973 88-29578 ISBN 0-520-06018-0 (alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of Figures and Tables ix Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall xi Preface xix Acknowledgements xxvii 1. A Secret Mission 1 2. The Eisenhower Imprint 17 3. The President and the Bomb 34 4. The Oppenheimer Case 73 5. The Political Arena 113 6. Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality 144 7. Nuclear Power for the Marketplace 183 8. Atoms for Peace: Building American Policy 209 9. Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom 238 10. The Seeds of Anxiety 271 11. Safeguards, EURATOM, and the International Agency 305 12. -

Compliance Investigation Report, Volume 1

70-820 UNC RECOVERY SYSTEMS COMPLIANCE INVESTIGATION REPORT VOLTIJE 1 - REPORT DETAILS Rvec'd wf ltr dtd 8J14/64 _/| 1 THEATTACHED FILES ARE OFFICIAL RECORDS OF THE INFORMATION & REPORTS MANAGEMENT BRANCH. THEY HAVE BEEN CHARGED TO YOU FOR A LIMITED TIME PERIOD AND c MUST BE RETURNED TO THE RE- CORDS & ARCHIVES SERVICES SEC- TION P1-22 WHITE FLINT. PLEASE DO NOT SEND DOCUMENTS CHARGED 5 OUT THROUGH THE MAIL. REMOVAL CD OF ANY PAGE(S) FROM DOCUMENT co FOR REPRODUCTION MUST BE RE- o FERRED TO FILE PERSONNEL. COMPLI.ANCE INVESTIGATION REPORT- o~is~nbf Compliae R~egion I ((3 S.ubject? UNITE-.D NUCLEAR CORPORATION4 Scrp_.eovery Facpi jo~olR ver'Junc pRhode Islaind Licen8e N~o.' SNH-777 Type ""casec CrttqjjcaSy Iictde~t: C5. teSo~IvsLaio tul : 25, .4t Auut7 1964 INN I ws-gt~nTa:WalteR~ ezi Ra04t~on Lot~i~ I p~~t'~'. wzmi 4pop ~~.; * t~41i Iny) goei-qU - I Vlue r RepQ0t Deal 7 - d~gk TABLE OF CONTENTS I Reason for Investigation 3 Criticality Investigation (Browne) ....................Page 1 Criticality Investigation (Crocker) ....................Page 27 1 (with attachments) Evaluation of Health Physics Program (Bresson) ........ Page 36 Decontamination Procedures (Lorenz)... ........ .. ....Page 59 Environmental Surveys (Brandkamp)..................... Page 65 Inquiry on Film Badge Evaluation (Knapp) .............. Page 76 Vehicle Survey (Knapp) ............................... Page 81 I Activities at Rhode Island Hospital (Resner) .......... Page 86 ' Activities in Exposure Evaluations (1kesner) ........... Page 103 I_ I.. l REASON FOR INVESTIGATION Initial telephone notification that there had been a criticality accident at a United Nuclear Corporation plant at about 6 p.m. was reportedly made by Mr. -

The Oratory of Dwight D. Eisenhower

The oratory of Dwight D. Eisenhower Book or Report Section Accepted Version Oliva, M. (2017) The oratory of Dwight D. Eisenhower. In: Crines, A. S. and Hatzisavvidou, S. (eds.) Republican orators from Eisenhower to Trump. Rhetoric, Politics and Society. Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 11-39. ISBN 9783319685441 doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68545-8 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/69178/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68545-8 Publisher: Palgrave MacMillan All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online THE ORATORY OF DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Dr Mara Oliva Department of History University of Reading [email protected] word count: 9255 (including referencing) 1 On November 4, 1952, Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower became the 34th President of the United States with a landslide, thus ending the Democratic Party twenty years occupancy of the White House. He also carried his Party to a narrow control of both the House of Representatives and the Senate. His success, not the Party’s, was repeated in 1956. Even more impressive than Eisenhower’s two landslide victories was his ability to protect and maintain his popularity among the American people throughout the eight years of his presidency. -

Timeline of the Cold War

Timeline of the Cold War 1945 Defeat of Germany and Japan February 4-11: Yalta Conference meeting of FDR, Churchill, Stalin - the 'Big Three' Soviet Union has control of Eastern Europe. The Cold War Begins May 8: VE Day - Victory in Europe. Germany surrenders to the Red Army in Berlin July: Potsdam Conference - Germany was officially partitioned into four zones of occupation. August 6: The United States drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima (20 kiloton bomb 'Little Boy' kills 80,000) August 8: Russia declares war on Japan August 9: The United States drops atomic bomb on Nagasaki (22 kiloton 'Fat Man' kills 70,000) August 14 : Japanese surrender End of World War II August 15: Emperor surrender broadcast - VJ Day 1946 February 9: Stalin hostile speech - communism & capitalism were incompatible March 5 : "Sinews of Peace" Iron Curtain Speech by Winston Churchill - "an "iron curtain" has descended on Europe" March 10: Truman demands Russia leave Iran July 1: Operation Crossroads with Test Able was the first public demonstration of America's atomic arsenal July 25: America's Test Baker - underwater explosion 1947 Containment March 12 : Truman Doctrine - Truman declares active role in Greek Civil War June : Marshall Plan is announced setting a precedent for helping countries combat poverty, disease and malnutrition September 2: Rio Pact - U.S. meet 19 Latin American countries and created a security zone around the hemisphere 1948 Containment February 25 : Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia March 2: Truman's Loyalty Program created to catch Cold War -

A Study Guide by Cheryl Jakab

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY CHERYL JAKAB http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-598-8 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Suitability: Highly recommended for science, arts and humanities Integrated study in Year 10 most Uranium has an atomic weight of 238. • We call it Uranium 238 and this U238 is the most commonly found Uranium on Earth. • In the world of atomic physics, these 238 protons and neutrons combine to make a huge nucleus. Running By contrast, the element Carbon usually has 12 time: protons and neutrons. This is why Uranium is often 3 x 51 mins described as a heavy element. approx • It’s this massive size of the nucleus at the centre of the Uranium atom that is the source of the strange energy first noticed by physicists at the turn of the 20th Century. We call it radiation. The great power that is • The central nucleus of the uranium atom struggles to hold itself together. We say it’s unstable. Uranium unleashed in ‘waking the spits out pieces of itself. Actual pieces, clumps of protons and neutrons and electrons and high energy dragon’ also involves great rays. This is radiation. risks. What are the costs and • When Uranium spits out this energy it changes it’s atomic weight. It goes from an atom with 238 the benefits of uranium? protons and neutrons at its centre, to an atom with a different number. » INTRODUCTION CONTENTS HYPERLINKS. CLICK ON ARROWS The year 2015 marks the seventieth anniversary of the most profound change in the history of human enterprise 3 The series at a glance on Earth: the unleashing of the elemental force within ura- nium, the explosion of an atomic bomb, the unleashing of 4 Overview of curriculum and education suitability the dragon. -

Eisenhower's Dilemma

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Eisenhower’s Dilemma How to Talk about Nuclear Weapons Paul Gregory Leahy 3/30/2009 Leahy 2 For Christopher & Michael, My Brothers Leahy 3 Table of Contents Introduction….6 Chapter 1: The General, 1945-1953….17 Chapter 2: The First Term, 1953-1957….43 Chapter 3: The Second Term, 1957-1961….103 Conclusion….137 Bibliography….144 Leahy 4 Acknowledgements I would to begin by taking a moment to thanks those individuals without whom this study would not be possible. Foremost among these individuals, I would like to thank Professor Jonathan Marwil, who had advised me throughout the writing of this thesis. Over countless hours he persistently pushed me to do better, work harder, and above all to write more consciously. His expert tutelage remains inestimable to me. I am gratified and humbled to have worked with him for these many months. I appreciate his patience and hope to have created something worth his efforts, as well as my own. I would like to thank the Department of History and the Honors Program for both enabling me to pursue my passion for history through their generous financial support, without which I could never have traveled to Abilene, Kansas. I would like to thank Kathy Evaldson for ensuring that the History Honors Thesis Program and the Department run smoothly. I also never could have joined the program were it not for Professor Kathleen Canning’s recommendation. She has my continued thanks. I would like to recognize and thank Professor Hussein Fancy for his contributions to my education. Similarly, I would like to recognize Professors Damon Salesa, Douglass Northrop, and Brian Porter-Szucs, who have all contributed to my education in meaningful and important ways. -

Environment and Natural Resources

A Guide To Historical Holdings in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library NATURAL RESOURCES AND THE ENVIRONMENT Compiled By DAVID J. HAIGHT August 1994 NATURAL RESOURCES AND THE ENVIROMENT A Guide to Historical Materials in the Eisenhower Library Introduction Most scholars do not consider the years of the Eisenhower Administration to be a period of environmental action. To many historians and environmentalists, the push for reform truly began with the publication in 1962 of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a critique of the use of pesticides, and the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964. The roots of this environmental activity, however, reach back to the 1950s and before, and it is therefore important to examine the documentary resources of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library. Following World War II, much of America experienced economic growth and prosperity. More Americans than ever before owned automobiles and labor saving household appliances. This increase in prosperity and mobility resulted in social changes which contain the beginnings of the modern environmental movement. With much more mobility and leisure time available more Americans began seeking recreation in the nation's forests, parks, rivers and wildlife refuges. The industrial expansion and increased travel, however, had its costs. The United States consumed great quantities of oil and became increasingly reliant on the Middle East and other parts of the world to supply the nation’s growing demand for fuel. Other sources of energy were sought and for some, atomic power appeared to be the answer to many of the nation’s energy needs. In the American West, much of which is arid, ambitious plans were made to bring prosperity to this part of the country through massive water storage and hydroelectric power projects. -

The Pre-History of Nuclear Development in Pakistan

Fevered with Dreams of the Future: The Coming of the Atomic Age to Pakistan* Zia Mian Too little attention has been paid to the part which an early exposure to American goods, skills, and American ways of doing things can play in forming the tastes and desires of newly emerging countries. President John F. Kennedy, 1963. On October 19, 1954, Pakistan’s prime minister met the president of the United States at the White House, in Washington. In Pakistan, this news was carried alongside the report that the Minister for Industries, Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan, had announced the establishment of an Atomic Energy Research Organization. These developments came a few months after Pakistan and the United States had signed an agreement on military cooperation and launched a new program to bring American economic advisers to Pakistan. Each of these initiatives expressed a particular relationship between Pakistan and the United States, a key moment in the coming into play of ways of thinking, the rise of institutions, and preparation of people, all of which have profoundly shaped contemporary Pakistan. This essay examines the period before and immediately after this critical year in which Pakistan’s leaders tied their national future to the United States. It focuses in particular on how elite aspirations and ideas of being modern, especially the role played by the prospect of an imminent ‘atomic age,’ shaped Pakistan’s search for U.S. military, economic and technical support to strengthen the new state. The essay begins by looking briefly at how the possibility of an ‘atomic age’ as an approaching, desirable global future took shape in the early decades of the twentieth century. -

Combined Film Catalog, 1972, United States Atomic Energy

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 067 273 SE 014 815 TITLE Combined FilmCatalog, 1972, United States Atomic Energy Commission.. INSTITUTION Atomic EnergyCommission, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 73p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Audiovisual Aids; Ecology; *Energy; *Environmental Education; Health Education; Instructional Materials; *Nuclear Physics; *Physical Sciences; Pollution; Radiation ABSTRACT A comprehensive listing of all current United States Atomic Energy Commission( USAEC) films, this catalog describes 232 films in two major film collections. Part One: Education-Information contains 17 subject categories and two series and describes 134 films with indicated understanding levels on each film for use by schools. The categories include such subjects as: Biology and Agriculture, Environment and Ecology, Industrial Applications, Medicine, Peaceful Uses, Power Reactors, and Research. Part Two: Technical-Professional lists 16 subject categories and describes 98 technical films for use primarily by professional audiences such as colleges and universities, industry, researchers, scientists, engineers and technologists. The subjects include: Engineering, Fuels, Medicine, Peaceful Nuclear Explosives, Physical Research, and Principles of Atomic Energy. All films are available from the five USAEC libraries listed. A section on "Advice To Borrowers" and request forms for ordering AEC films follow. (LK) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EOUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIG INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY RF °RESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OFEDU CATION POSITION OR POLICY 16 mm A A I I I University of Alaska Film Library NOTICE Atomic Energy Film Section Division of Public Service With theissuanceof this 1972 catalog, the USAEC 109 Eielson Building announces that allthe domestic film libraries (except College, Alaska 99701 Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico) have been consolidated Phone:907-479-7296 into one new library. -

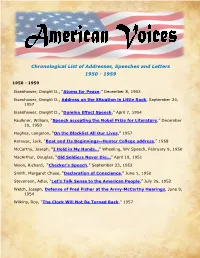

Chronological List of Addresses, Speeches and Letters 1950 - 1959

Chronological List of Addresses, Speeches and Letters 1950 - 1959 1950 - 1959 Eisenhower, Dwight D., “Atoms for Peace,” December 8, 1953 Eisenhower, Dwight D., Address on the Situation in Little Rock, September 24, 1957 Eisenhower, Dwight D., “Domino Effect Speech,” April 7, 1954 Faulkner, William, “Speech accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature,” December 10, 1950 Hughes, Langston, “On the Blacklist All Our Lives,” 1957 Kerouac, Jack, “Beat and Its Beginnings—Hunter College address,” 1958 McCarthy, Joseph, “I Hold in My Hands…” Wheeling, WV Speech, February 9, 1950 MacArthur, Douglas, “Old Soldiers Never Die…” April 19, 1951 Nixon, Richard, “Checker’s Speech,” September 23, 1952 Smith, Margaret Chase, “Declaration of Conscience,” June 1, 1950 Stevenson, Adlai, “Let’s Talk Sense to the American People,” July 26, 1952 Welch, Joseph, Defense of Fred Fisher at the Army-McCarthy Hearings, June 9, 1954 Wilkins, Roy, “The Clock Will Not Be Turned Back,” 1957 SOURCE: http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/dwightdeisenhoweratomsforpeace.html Eisenhower, Dwight D., Atoms for Peace, December 8, 1953 *Madam President and* Members of the General Assembly: When Secretary General Hammarskjold’s invitation to address this General Assembly reached me in Bermuda, I was just beginning a series of conferences with the Prime Ministers and Foreign Ministers of Great Britain and of France. Our subject was some of the problems that beset our world. During the remainder of the Bermuda Conference, I had constantly in mind that ahead of me lay a great honor. That honor is mine today, as I stand here, privileged to address the General Assembly of the United Nations. -

Atoms for Peace Organized by The

Atoms for Peace Organized by the International Atomic Energy Agency In cooperation with the OECD/Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) World Nuclear Association (WNA) The material in this book has been supplied by the authors and has not been edited. The views expressed remain the responsibility of the named authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the government of the designating Member State(s). The IAEA cannot be held responsible for any material reproduced in this book. International Symposium on Uranium Raw Material for the Nuclear Fuel Cycle: Exploration, Mining, Production, Supply and Demand, Economics and Environmental Issues (URAM-2009) ABSTRACTS Title Author (s) Page T0 - OPENING SESSION Address of Symposium President: The uranium world in F. J. Dahlkamp 1 9 transition from stagnancy to revival IAEA activities on uranium resources and production and C. Ganguly, J. Slezak 2 13 databases for the nuclear fuel cycle 3 A long-term view of uranium supply and demand R. Vance 15 T1 - URANIUM MARKETS & ECONOMICS ORAL PRESENTATIONS 4 Nuclear power has a bright outlook and information on G. Capus 19 uranium resources is our duty 5 Uranium Stewardship – the unifying foundation M. Roche 21 6 Safeguards obligations related to uranium/thorium mining A. Petoe 23 and processing 7 A review of uranium resources, production and exploration A. McKay, I. Lambert, L. Carson 25 in Australia 8 Paradigmatic shifts in exploration process: The role of J. Marlatt, K. Kyser 27 industry-academia collaborative research and development in discovering the next generation of uranium ore deposits 9 Uranium markets and economics: Uranium production cost D.