Culture, Cold War, Conservatism, and the End of the Atomic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons

VERSION: Charles P. Blair, “Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons,” in Gary Ackerman and Jeremy Tamsett, eds., Jihadists and Weapons of Mass Destruction: A Growing Threat (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2009), pp. 193-238. c h a p t e r 8 Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons Charles P. Blair CONTENTS Introduction 193 Improvised Nuclear Devices (INDs) 195 Fissile Materials 198 Weapons-Grade Uranium and Plutonium 199 Likely IND Construction 203 External Procurement of Intact Nuclear Weapons 204 State Acquisition of an Intact Nuclear Weapon 204 Nuclear Black Market 212 Incidents of Jihadist Interest in Nuclear Weapons and Weapons-Grade Nuclear Materials 213 Al-Qa‘ida 213 Russia’s Chechen-Led Jihadists 214 Nuclear-Related Threats and Attacks in India and Pakistan 215 Overall Likelihood of Jihadists Obtaining Nuclear Capability 215 Notes 216 Appendix: Toward a Nuclear Weapon: Principles of Nuclear Energy 232 Discovery of Radioactive Materials 232 Divisibility of the Atom 232 Atomic Nucleus 233 Discovery of Neutrons: A Pathway to the Nucleus 233 Fission 234 Chain Reactions 235 Notes 236 INTRODUCTION On December 1, 2001, CIA Director George Tenet made a hastily planned, clandestine trip to Pakistan. Tenet arrived in Islamabad deeply shaken by the news that less than three months earlier—just weeks before the attacks of September 11, 2001—al-Qa‘ida and Taliban leaders had met with two former Pakistani nuclear weapon scientists in a joint quest to acquire nuclear weapons. Captured documents the scientists abandoned as 193 AU6964.indb 193 12/16/08 5:44:39 PM 194 Charles P. Blair they fled Kabul from advancing anti-Taliban forces were evidence, in the minds of top U.S. -

Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I

Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I November 4 - 7, 2002 Richland, WA FINAL REPORT A Collaborative Workshop: United States Fish & Wildlife Service The Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN) Hanford Reach National Monument 1 Planning Workshop I, November 2002 A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group in collaboration with the United States Fish & Wildlife Service. CBSG. 2002. Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I. FINAL REPORT. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. 2 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I, November 2002 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I November 4-7, 2002 Richland, WA TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1. Executive Summary 1 A. Introduction and Workshop Process B. Draft Vision C. Draft Goals 2. Understanding the Past 11 A. Personal, Local and National Timelines B. Timeline Summary Reports 3. Focus on the Present 31 A. Prouds and Sorries 4. Exploring the Future 39 A. An Ideal Future for Hanford Reach National Monument B. Goals Appendix I: Plenary Notes 67 Appendix II: Participant Introduction questions 79 Appendix III: List of Participants 87 Appendix IV: Workshop Invitation and Invitation List 93 Appendix V: About CBSG 103 Hanford Reach National Monument 3 Planning Workshop I, November 2002 4 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I, November 2002 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I November 4-7, 2002 Richland, WA Section 1 Executive Summary Hanford Reach National Monument 5 Planning Workshop I, November 2002 6 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I, November 2002 Executive Summary A. Introduction and Workshop Process Introduction to Comprehensive Conservation Planning This workshop is the first of three designed to contribute to the Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) of Hanford Reach National Monument. -

Excerpt from the Yakima Nation/Cleanup of Hanford

DOE Indian Policy and Treaty Obligations Excerpt from The Yakama Nation and the Cleanup of Hanford: Contested Meanings of Environmental Remediation written by Daniel A. Bush (2014) http://nativecases.evergreen.edu/collection/cases/the-yakama-nation-and-the-cleanup- of-hanford-contested-meanings-of-environmental-remediation Map: Yakama Reservation and lands ceded by the Yakama in the 1855 treaty (Klickitat Library Images, 2014) According to the DOE’s Tribal Program, “the involvement [of] Native American Tribes at Hanford is guided by DOE's American Indian Policy [which] states that it is the trust responsibility of the United States to protect tribal sovereignty and self-determination, tribal lands, assets, resources, and treaty and other federal recognized and reserved rights” (Department of Energy (DOE) Tribal Program, 2014). Therefore, where Native Americans are concerned it would seem that the DOE has a legal obligation to restore the Hanford site to its pre-nuclear state. It could also be argued that Native tribes have their own trust responsibility for preservation of natural resources on both tribal lands and those areas of traditional use. Moreover, the web of responsibilities associated with the Hanford cleanup are complicated by potential liabilities, as Native peoples have a right to “damages for injuries which occur to natural resources as a result of hazardous waste release” (Bauer, 1994). Thus, Native Americans who traditionally used the affected area have also been involved in the cleanup of Hanford. CERCLA itself named Native tribes as having a vested interest in Superfund sites such as Hanford. The DOE agrees that the Nez Perce Tribe, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Indian Nation, and Wanapum native peoples be regularly consulted throughout the cleanup process and that all have rights to resources in the 1 Hanford region. -

Compliance Investigation Report, Volume 1

70-820 UNC RECOVERY SYSTEMS COMPLIANCE INVESTIGATION REPORT VOLTIJE 1 - REPORT DETAILS Rvec'd wf ltr dtd 8J14/64 _/| 1 THEATTACHED FILES ARE OFFICIAL RECORDS OF THE INFORMATION & REPORTS MANAGEMENT BRANCH. THEY HAVE BEEN CHARGED TO YOU FOR A LIMITED TIME PERIOD AND c MUST BE RETURNED TO THE RE- CORDS & ARCHIVES SERVICES SEC- TION P1-22 WHITE FLINT. PLEASE DO NOT SEND DOCUMENTS CHARGED 5 OUT THROUGH THE MAIL. REMOVAL CD OF ANY PAGE(S) FROM DOCUMENT co FOR REPRODUCTION MUST BE RE- o FERRED TO FILE PERSONNEL. COMPLI.ANCE INVESTIGATION REPORT- o~is~nbf Compliae R~egion I ((3 S.ubject? UNITE-.D NUCLEAR CORPORATION4 Scrp_.eovery Facpi jo~olR ver'Junc pRhode Islaind Licen8e N~o.' SNH-777 Type ""casec CrttqjjcaSy Iictde~t: C5. teSo~IvsLaio tul : 25, .4t Auut7 1964 INN I ws-gt~nTa:WalteR~ ezi Ra04t~on Lot~i~ I p~~t'~'. wzmi 4pop ~~.; * t~41i Iny) goei-qU - I Vlue r RepQ0t Deal 7 - d~gk TABLE OF CONTENTS I Reason for Investigation 3 Criticality Investigation (Browne) ....................Page 1 Criticality Investigation (Crocker) ....................Page 27 1 (with attachments) Evaluation of Health Physics Program (Bresson) ........ Page 36 Decontamination Procedures (Lorenz)... ........ .. ....Page 59 Environmental Surveys (Brandkamp)..................... Page 65 Inquiry on Film Badge Evaluation (Knapp) .............. Page 76 Vehicle Survey (Knapp) ............................... Page 81 I Activities at Rhode Island Hospital (Resner) .......... Page 86 ' Activities in Exposure Evaluations (1kesner) ........... Page 103 I_ I.. l REASON FOR INVESTIGATION Initial telephone notification that there had been a criticality accident at a United Nuclear Corporation plant at about 6 p.m. was reportedly made by Mr. -

The Atomic Energy Commission

The Atomic Energy Commission By Alice Buck July 1983 U.S. Department of Energy Office of Management Office of the Executive Secretariat Office of History and Heritage Resources Introduction Almost a year after World War II ended, Congress established the United States Atomic Energy Commission to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. Reflecting America's postwar optimism, Congress declared that atomic energy should be employed not only in the Nation's defense, but also to promote world peace, improve the public welfare, and strengthen free competition in private enterprise. After long months of intensive debate among politicians, military planners and atomic scientists, President Harry S. Truman confirmed the civilian control of atomic energy by signing the Atomic Energy Act on August 1, 1946.(1) The provisions of the new Act bore the imprint of the American plan for international control presented to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission two months earlier by U.S. Representative Bernard Baruch. Although the Baruch proposal for a multinational corporation to develop the peaceful uses of atomic energy failed to win the necessary Soviet support, the concept of combining development, production, and control in one agency found acceptance in the domestic legislation creating the United States Atomic Energy Commission.(2) Congress gave the new civilian Commission extraordinary power and independence to carry out its awesome responsibilities. Five Commissioners appointed by the President would exercise authority for the operation of the Commission, while a general manager, also appointed by the President, would serve as chief executive officer. To provide the Commission exceptional freedom in hiring scientists and professionals, Commission employees would be exempt from the Civil Service system. -

A Study Guide by Cheryl Jakab

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY CHERYL JAKAB http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-598-8 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Suitability: Highly recommended for science, arts and humanities Integrated study in Year 10 most Uranium has an atomic weight of 238. • We call it Uranium 238 and this U238 is the most commonly found Uranium on Earth. • In the world of atomic physics, these 238 protons and neutrons combine to make a huge nucleus. Running By contrast, the element Carbon usually has 12 time: protons and neutrons. This is why Uranium is often 3 x 51 mins described as a heavy element. approx • It’s this massive size of the nucleus at the centre of the Uranium atom that is the source of the strange energy first noticed by physicists at the turn of the 20th Century. We call it radiation. The great power that is • The central nucleus of the uranium atom struggles to hold itself together. We say it’s unstable. Uranium unleashed in ‘waking the spits out pieces of itself. Actual pieces, clumps of protons and neutrons and electrons and high energy dragon’ also involves great rays. This is radiation. risks. What are the costs and • When Uranium spits out this energy it changes it’s atomic weight. It goes from an atom with 238 the benefits of uranium? protons and neutrons at its centre, to an atom with a different number. » INTRODUCTION CONTENTS HYPERLINKS. CLICK ON ARROWS The year 2015 marks the seventieth anniversary of the most profound change in the history of human enterprise 3 The series at a glance on Earth: the unleashing of the elemental force within ura- nium, the explosion of an atomic bomb, the unleashing of 4 Overview of curriculum and education suitability the dragon. -

Dixy Lee Ray, Marine Biology, and the Public Understanding of Science in the United States (1930-1970)

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Erik Ellis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Science presented on November 21. 2005. Title: Dixy Lee Ray. Marine Biology, and the Public Understanding of Science in the United States (1930-1970) Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy This dissertation focuses on the life of Dixy Lee Ray as it examines important developments in marine biology and biological oceanography during the mid twentieth century. In addition, Ray's key involvement in the public understanding of science movement of the l950s and 1960s provides a larger social and cultural context for studying and analyzing scientists' motivations during the period of the early Cold War in the United States. The dissertation is informed throughout by the notion that science is a deeply embedded aspect of Western culture. To understand American science and society in the mid twentieth century it is instructive, then, to analyze individuals who were seen as influential and who reflected widely held cultural values at that time. Dixy Lee Ray was one of those individuals. Yet, instead of remaining a prominent and enduring figure in American history, she has disappeared rapidly from historical memory, and especially from the history of science. It is this very characteristic of reflecting her time, rather than possessing a timeless appeal, that makes Ray an effective historical guide into the recent past. Her career brings into focus some of the significant ways in which American science and society shifted over the course of the Cold War. Beginning with Ray's early life in West Coast society of the1920sandl930s, this study traces Ray's formal education, her entry into the professional ranks of marine biology and the crucial role she played in broadening the scope of biological oceanography in the early1960s.The dissertation then analyzes Ray's efforts in public science education, through educational television, at the science and technology themed Seattle World's Fair, and finally in her leadership of the Pacific Science Center. -

Charles Z. Smith Papers File://///Files/Shareddocs/Librarycollections/Manuscriptsarchives/Findaidsi

Charles Z. Smith papers file://///files/shareddocs/librarycollections/manuscriptsarchives/findaidsi... UNIVERSITY UBRARIES w UNIVERSITY of WASH INCTON Spe, ial Colle tions. Charles Z. Smith papers Inventory Accession No: 3306-001 Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Guide to the Charles Z. Smith Papers. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/SmithCharlesZUA3306/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search 1 of 1 8/19/2015 6:33 PM CHARLES Z. SMITH Accession No. 3306-83-5 INVENTORY Box Seri es Folders Dates BIOGRAPH I CAL FEATURES GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE A - Z 5 1973-80 Unsorted Correspondence l 966-79 American Jewish Committee 1974 American Judicature Society 1973-74 Atlantic Richfield Company 1977 First Baptist Church 1976-81 National College of Criminal Defense Lawyers and Public Defenders 1973-75 National College of the State Judiciary 1975-76 Seattle (correspondence with various offices) 1974-78 Seattle. Pol ice Department 1971-80 Seattle . Schools 1974-80 Seattle-King County Public Defender 1972-79 United States (correspondence with various governmental departments) 1974 U. S. Defense Department. Military Appeals Court 1979 U.S. Health, Education and Welfare Department 1974-79 University of Puget Sound. Law School 1973-77 Washington (correspondence with various governmental departments) 1974-78 Washington. Governor (Daniel J. Evans) 1966-76 Washington . Governor (Dixy Lee Ray) 1976-80 Washington. -

October 11, 1992 MEMORANDUM to the LEADER FROM: JOHN

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu October 11, 1992 MEMORANDUM TO THE LEADER FROM: JOHN DIAMANTAKIOU SUBJECT: POLITICAL BRIEFINGS Below is an outline of your briefing materials for your appearances throughout the month of October. Enclosed for your perusal are: 1. Campaign briefing: • overview of race • biographical materials • Bills introduced in 102nd Congress 2. National Republican Senatorial Briefing 3. City Stop/District race overview 4. Governor's race brief (WA, UT, MO) 5. Redistricting map/Congressional representation 6. NAFTA Brief 7. Republican National Committee Briefing 8. State Statistical Summary 9. State Committee/DFP supporter contact list 10 Clips (courtesy of the campaigns) 11. Political Media Recommendations (Clarkson/Walt have copy) Thank you. Page 1 of 72 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas 10-08-1992 08=49RM FROM CHANDLER 92http://dolearchives.ku.edu TO 12022243163 P.02 CHANDLER-~2 MEMORANDUM TO: John Diamantakiou FR: Kraig Naasz RE: Senator Dole's Visit DT: October 7, 1992 I On Rod's be9Flf, I want to thank you for all your help. I hope the followinj information and attachments are of assistance to you and Senator Doi 11e. · I 1!,! I Primary Election In Washington's open primary, Rod finished first ahead of Leo Thorsness and Tim Hill with 21% of the vote. Patty Murray, who had only one Democrat foe, finished with 29% of the vote. No independent candidate qualified for the general election ballot. A total of 541, 267 votes were cast for one of the three Republicans in the primary (48.6% of the vote). -

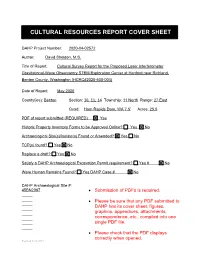

Cultural Resources Report Cover Sheet

CULTURAL RESOURCES REPORT COVER SHEET DAHP Project Number: 2020-04-02572 Author: David Sheldon, M.S. Title of Report: Cultural Survey Report for the Proposed Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory STEM Exploration Center at Hanford near Richland, Benton County, Washington (HCRC#2020-600-004) Date of Report: May 2020 County(ies): Benton Section: 10, 11, 14 Township: 11 North Range: 27 East Quad: Horn Rapids Dam, WA 7.5’ Acres: 25.5 PDF of report submitted (REQUIRED) Yes Historic Property Inventory Forms to be Approved Online? Yes No Archaeological Site(s)/Isolate(s) Found or Amended? Yes No TCP(s) found? Yes No Replace a draft? Yes No Satisfy a DAHP Archaeological Excavation Permit requirement? Yes # No Were Human Remains Found? Yes DAHP Case # No DAHP Archaeological Site #: 45BN2067 • Submission of PDFs is required. • Please be sure that any PDF submitted to DAHP has its cover sheet, figures, graphics, appendices, attachments, correspondence, etc., compiled into one single PDF file. • Please check that the PDF displays correctly when opened. Revised 9-26-2018 Proposed Laser Interferometer Gravitational- Wave Observatory STEM Exploration Center at Hanford near Richland, Benton County, Washington Cultural Survey Report HCRC#2020-600-004 Final May 7, 2020 Prepared for: National Science Foundation Document No. (JETT) Cultural Survey Report HCRC#2020-600-004 Executive Summary The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) is a national facility for gravitational- wave research. LIGO is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and operated by the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The interferometer in Hanford, Washington (LIGO Hanford) is located on land owned by the United States and administered by the U.S. -

Decaying in Storage: the Closures of Three Nuclear Reactors in the Pacific Northwest

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Celia Oney for the degree of Master of Arts in History and Philosophy of Science presented on June 7, 2021. Title: Decaying in Storage: The Closures of Three Nuclear Reactors in the Pacific Northwest Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Jacob Darwin Hamblin People involved in a nuclear activity, whether they are developing it, benefiting from it, or opposing it, see inherent connections between various aspects of nuclear science and technology. This thesis investigates three nuclear sites: a university research reactor, a dual-purpose reactor that produced plutonium for the U.S. military and electricity for civilian use, and a commercial power reactor, all located in the Pacific Northwest. It examines the decisions that led to the closure and disposal of these reactors and the ways these decisions were influenced by factors that were more directly related to other forms of nuclear science and technology. Each site had both obvious nuclearity as an example of nuclear reactor technology and hidden nuclearity that came from the ways people connected these reactors with other kinds of nuclear activities. Oregon State University attempted to give its AGN-201 research reactor to several other institutions, but each arrangement was complicated by one of the factors that made it desirable: the AEC’s involvement in both promoting and regulating nuclear reactors, the possible ties between research reactors and nuclear weapons development, and the reactor’s utility as a training tool for future nuclear power industry workers. The N Reactor at the Hanford site closed down due to the nearly simultaneous occurrence of several factors: new public knowledge of the radioactive contamination that Hanford had released over several decades, increased scrutiny following the Chernobyl disaster, and a senator with moral objections to nuclear weapons in a position that gave him influence over Hanford’s budget. -

"Blessing" of Atomic Energy in the Early Cold War Era

International Journal of Korean History (Vol.19 No.2, Aug. 2014) 107 The Atoms for Peace USIS Films: Spreading the Gospel of the "Blessing" of Atomic Energy in the Early Cold War Era Tsuchiya Yuka* Introduction In 1955 Blessing of Atomic Agency (原子力の恵み) was released. It was a 30-minute documentary made by the US Information Service in Tokyo to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshi- ma and Nagasaki. The film featured Japanese progress in “peaceful uses” of atomic energy, especially the use of radio-isotopes from the US Ar- gonne National Laboratory. They were widely used in Japanese scientific laboratories, national institutions and private companies in various fields including agriculture, medicine, industry, and disaster prevention. The film also introduced the nuclear power generation method, mentioning the commercial use of this technology in the US and Europe. It depicted Ja- pan as a nation that overcame the defeat of war and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, enjoying the “blessing” of atomic energy, and striving to become a powerful country with science and technology. Not only was this film screened at American Centers, schools, or village halls all across Japan, but it was also translated into various different lan- * Professor, International/American Studies, Ehime University. 108 The Atoms for Peace USIS Films guages and screened in over 18 countries including the UK, Finland, In- donesia, Sudan, and Venezuela. Blessing of Atomic Agency was one of some 50 USIS films (govern- ment-sponsored information/education films) produced as part of the “Atoms for Peace” campaign launched by the US Eisenhower administra- tion (1953-1960).