The Atomic Energy Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People and Things

People and things John Cumalat and David Neuffer, first Robert R. Wilson Fellows at Fermilab. The Wilson fellowships are special three year appointments awarded annually at Fermilab to outstanding young physicists in the fields of accelerators and particle physics. On people Accelerator specialist Ernie Courant is the recipient of the 1979 Boris Pregel A ward for Applied Science and Technology. The presentation was made at the annual meeting of the New York Academy of Sciences on 6 December. Giving cancer treatments at TRIUMF The first treatment of cancer patients began at TRIUMF in Nov ember using the negative pion beam from the biomedical channel. In this first series, patients with multiple skin tumour nodules are receiving ten daily treatments. In order to assess the effect of negative pions on human tissue, some of the nodules are being treated with pions and others with X-rays. Only when this is known can treatment of larger, deep-seated tumours com mence. The treatments at TRIUMF have been preceded by comprehen sive pre-clinical investigations in cluding both physical and radiobio logical studies, the latter including cultured cells, mice and pigs. Conferences on the horizon The Sixth International Conference on Experimental Meson Spectro scopy will be held at Brookhaven on 24-25 April. The Conference will cover experimental results in light and heavy quark spectroscopy, rele vant theory and spectrometer sys tems. For further information please contact CU. Chung or S.J. Linden- baum, Brookhaven National Labo ratory, Upton, New York 11973. The Mark II detector, previously used in experiments at SPEAR, seen here being installed in one of the experimental areas of the new PEP electron-positron collider. -

Atoms for Peace: Eisenhower and Nuclear Technology

NATIONAL EISENHOWER MEMORIAL EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS LESSON Atoms for Peace: Eisenhower and Nuclear Technology Duration One 45-minute period Grades 7–12 Cross-curriculum Application U.S. History, World History, Media Arts NATIONAL EISENHOWER MEMORIAL LESSON: ATOMS FOR PEACE | 1 EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS Historical Background The advancement of nuclear technology and the subsequent devastation to Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945 from atomic bombs dropped on them during the final stages of World War II introduced a completely new means of waging war to the world. The fears that Americans associ- ated with nuclear weapons only increased as first the Soviet Union and then communist China developed their own atomic bombs. The issue of nuclear power was not just a problem for America but a global challenge, compli- cated largely by the lack of scientific data regarding military effect and environmental impact. It was within this context that Eisenhower took the unprecedented step of promoting the use of atoms for peace rather than for war. To convince Americans that nuclear power had positive benefits for the country, the federal government under Eisenhower launched a program called “Atoms for Peace.” The program took its name from a stunning speech delivered by Eisenhower to the United Nations General Assembly in 1953. Eisenhower believed that “the only way to win World War III is to prevent it.” He recommended the creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to help diffuse political tensions and solve the “fearful atomic dilemma” by both monitoring atomic weapons and support- ing research into peaceful uses for atomic energy such as medicine and agriculture. -

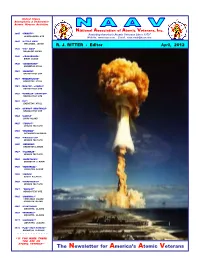

2012 04 Newsletter

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor April, 2012 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSTON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSTON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ ENEWETAK CLEANUP ------------ “ IF YOU WERE THERE, YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDER’S COMMENTS knowing the seriousness of the situation, did not register any Outreach Update: First, let me extend our discomfort, or dissatisfaction on her part. As a matter of fact, it thanks to the membership and friends of NAAV was kind of nice to have some of those callers express their for supporting our “outreach” efforts over the thanks for her kind attention and assistance. We will continue past several years. It is that firm dedication to to insure that all inquires, along these lines, are fully and our Mission-Statement that has driven our adequately addressed. -

Nuclear Technology

Nuclear Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. GREENWOOD PRESS NUCLEAR TECHNOLOGY Sourcebooks in Modern Technology Space Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. Sourcebooks in Modern Technology Nuclear Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Angelo, Joseph A. Nuclear technology / Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. p. cm.—(Sourcebooks in modern technology) Includes index. ISBN 1–57356–336–6 (alk. paper) 1. Nuclear engineering. I. Title. II. Series. TK9145.A55 2004 621.48—dc22 2004011238 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2004 by Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004011238 ISBN: 1–57356–336–6 First published in 2004 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 To my wife, Joan—a wonderful companion and soul mate Contents Preface ix Chapter 1. History of Nuclear Technology and Science 1 Chapter 2. Chronology of Nuclear Technology 65 Chapter 3. Profiles of Nuclear Technology Pioneers, Visionaries, and Advocates 95 Chapter 4. How Nuclear Technology Works 155 Chapter 5. Impact 315 Chapter 6. Issues 375 Chapter 7. The Future of Nuclear Technology 443 Chapter 8. Glossary of Terms Used in Nuclear Technology 485 Chapter 9. Associations 539 Chapter 10. -

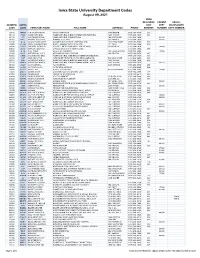

Iowa State University Department Codes

Iowa State University Department Codes August 09, 2021 RMM RESOURCE PARENT CROSS- NUMERIC ALPHA UNIT DEPT DISCIPLINARY CODE CODE DIRECTORY NAME FULL NAME ADDRESS PHONE NUMBER NUMBER DEPT NUMBER 30141 4HFDN 4-H FOUNDATION 4-H FOUNDATION 2150 BDSHR (515) 294-5390 030 01130 A B E AG/BIOSYS ENG AGRICULTURAL & BIOSYSTEMS ENGINEERING 1201 SUKUP (515) 294-1434 001 01132 A E AG ENGINEERING AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING 100 DAVIDSON (515) 294-1434 01130 01581 A ECL ANIMAL ECOLOGY ANIMAL ECOLOGY 253 BESSEY (515) 294-1458 01580 92290 A I C ACUMEN IND CORP ACUMEN INDUSTRIES CORPORATION 1613 RSRC PARK (515) 296-5366 999 45000 A LAB AMES LABORATORY AMES LABORATORY OF US DOE 151 TASF (515) 294-2680 020 10106 A M D APPAREL MERCH D APPAREL MERCHANDISING AND DESIGN 31 MACKAY (515) 294-7474 10100 80620 A S C APPL SCI COMPUT APPLIED SCIENTIFIC COMPUTING (515) 294-2694 999 10706 A TR ATH TRAIN ATHLETIC TRAINING 235 FORKER BLDG (515) 294-8009 10700 07040 A V C ART/VISUAL CULT ART AND VISUAL CULTURE 146 DESIGN (515) 294-5676 007 70060 A&BE AG & BIOSYS ENG AGRICULTURAL AND BIOSYSTEMS ENGINEERING (515) 294-1434 999 92100 AAT ADV ANAL TCH ADVANCED ANALYTICAL TECHNOLOGIES INC ISU RSRC PARK (515) 296-6600 999 02010 ABE AG/BIOSYS ENG-E AGRICULTURAL & BIOSYSTEMS ENGR - ENGR 1201 SUKUP (515) 294-1434 002 01136 ABE A AG/BIOSYS ENG-A AGRICULTURAL & BIOSYSTEMS ENGR - AGLS 1201 SUKUP (515) 294-1434 01130 08100 ACCT ACCOUNTING ACCOUNTING 2330 GERDIN (515) 294-8106 008 08301 ACSCI ACTUARIAL SCI ACTUARIAL SCIENCE (515) 294-4668 008 10501 AD ED ADULT ED ADULT EDUCATION N131 LAGOMAR -

Chapter 4. CLASSIFICATION UNDER the ATOMIC ENERGY

Chapter 4 CLASSIFICATION UNDER THE ATOMIC ENERGY ACT INTRODUCTION The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 was the first and, other than its successor, the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, to date the only U.S. statute to establish a program to restrict the dissemination of information. This Act transferred control of all aspects of atomic (nuclear) energy from the Army, which had managed the government’s World War II Manhattan Project to produce atomic bombs, to a five-member civilian Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). These new types of bombs, of awesome power, had been developed under stringent secrecy and security conditions. Congress, in enacting the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, continued the Manhattan Project’s comprehensive, rigid controls on U.S. information about atomic bombs and other aspects of atomic energy. That Atomic Energy Act designated the atomic energy information to be protected as “Restricted Data” and defined that data. Two types of atomic energy information were defined by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, Restricted Data (RD) and a type that was subsequently termed Formerly Restricted Data (FRD). Before discussing further the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 and its unique requirements for controlling atomic energy information, some of the special information-control activities that accompanied the research, development, and production efforts that led to the first atomic bomb will be mentioned. Realization that an atomic bomb was possible had a profound impact on the scientists who first became aware of that possibility. The implications of such a weapon were so tremendous that the U.S. scientists conducting the initial, basic research related to nuclear fission voluntarily restricted the publication of their scientific work in this area. -

Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. Atoms

ATOMS PEACE WAR Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission Richard G. Hewlett and lack M. Roll With a Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall and an Essay on Sources by Roger M. Anders University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Published 1989 by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission; work made for hire. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewlett, Richard G. Atoms for peace and war, 1953-1961. (California studies in the history of science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Nuclear energy—United States—History. 2. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—History. 3. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890-1969. 4. United States—Politics and government-1953-1961. I. Holl, Jack M. II. Title. III. Series. QC792. 7. H48 1989 333.79'24'0973 88-29578 ISBN 0-520-06018-0 (alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of Figures and Tables ix Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall xi Preface xix Acknowledgements xxvii 1. A Secret Mission 1 2. The Eisenhower Imprint 17 3. The President and the Bomb 34 4. The Oppenheimer Case 73 5. The Political Arena 113 6. Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality 144 7. Nuclear Power for the Marketplace 183 8. Atoms for Peace: Building American Policy 209 9. Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom 238 10. The Seeds of Anxiety 271 11. Safeguards, EURATOM, and the International Agency 305 12. -

The United States Nuclear Weapon Program

/.i. - y _-. --_- -. : _ - . i - DOE/ES4005 (Draft) I _ __ _ _ _____-. 67521 - __ __-. -- -- .-- THE UNITED STATES NUCLEAR - %”WEAPQN PROGRA,hik ..I .La;*I* . , ASUMMARYHISTORY \ ;4 h : . ,‘f . March 1983 \ .;_ U.S. Department of Energy Assistant Secretary, Management and Administration Office of The Executive Secretariat History Division -. DOE/ES4005 (Draft) THE UNITED STATES NUCLEAR WEAPON PROG.RAM: ASUMMARYHISTORY .' . c *. By: . Roger M. Anders Archivist With: Jack M. Hall Alice L. Buck Prentice C. Dean March 1983 ‘ .I \ . U.S. Department of Energy Assistant Secretary, Management and Administration Office of The Executive Secretariat History Division Washington, D. C. 20585 ‘Thelkpaemlt of Energy OqanizationAct of 1977 b-mughttcgether for the first tim in one departxrmtrmst of the Federal GovenmTle?t’s - Programs-With these programs cam a score of organizational ‘ . ? entities,eachwithi+ccxmhistoryandtraditions,frmadozendepart- . .‘I w ’ mnts and independentagencies. The EIistoryDivision,- prepareda . seriesof paqhlets on The Institutional Originsof the De-t of v Eachpamphletexplainsthehistory,goals,and achievemzntsof a predecessoragency or a major prqrm of the -to=-TY* This parquet, which replacesF&ger M. Anders'previous booklet on "The Office of MilitaxxApplication," traces the histoe of the UrL+& Statesnuclearweapx prcgramfrmits inceptionduring World War II to the present. Nuclear weqons form the core of America's m&z defenses. Anders'history describes the truly fo&idable effortscf 5e Atanic Energy Cmmission, the F;nergy Rfzsearch and Develqmlt z4dmCstratian,andtheDep&m- to create adiverse a* sophistica~arsenzl ofnucleaz ~accctqli&mentsofL~se agenciesandtheirplants andlabc J zrsatedan "atanic shie2 WMchp- Psrrericatoday. r kger M. Anders is a trained historianworking in the Eistzq Divisbn. -

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Paul Harold Rubinson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War Committee: —————————————————— Mark A. Lawrence, Supervisor —————————————————— Francis J. Gavin —————————————————— Bruce J. Hunt —————————————————— David M. Oshinsky —————————————————— Michael B. Stoff Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War by Paul Harold Rubinson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Acknowledgements Thanks first and foremost to Mark Lawrence for his guidance, support, and enthusiasm throughout this project. It would be impossible to overstate how essential his insight and mentoring have been to this dissertation and my career in general. Just as important has been his camaraderie, which made the researching and writing of this dissertation infinitely more rewarding. Thanks as well to Bruce Hunt for his support. Especially helpful was his incisive feedback, which both encouraged me to think through my ideas more thoroughly, and reined me in when my writing overshot my argument. I offer my sincerest gratitude to the Smith Richardson Foundation and Yale University International Security Studies for the Predoctoral Fellowship that allowed me to do the bulk of the writing of this dissertation. Thanks also to the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University, and John Gaddis and the incomparable Ann Carter-Drier at ISS. -

CHAPTER IX HEALTH New York, 22 July 1946 .ENTRY INTO FORCE: 7 April 1948, in Accordance with Article 80. REGISTRATION

CHAPTER IX HEALTH 1. CONSTITUTION OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION New York, 22 July 1946 ENTRY. INTO FORCE: 7 April 1948, in accordance with article 80. REGISTRATION: 7 April 1948, No. 221. STATUS: Signatories: 59. Parties: 193. TEXT: United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 14, p. 185 (with regard to the text of subsequent amendments, see further under each series of amendments). Note: The Constitution was drawn up by the International Health Conference, which had been convened pursuant to resolution l (I)1 of the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations, adopted on 15 February 1946. The Conference was held at New York from 19 June to 22 July 1946. In addition to the Constitution, the Conference drew up the Final Act, the Arrangements for the Establishment of an Interim Commission of the World Health Organization and the Protocol concerning the Office international d'hygiène publique , for the text of which, see United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 9, p. 3. Definitive Definitive signature(s), signature(s), Participant2,3,4 Signature Acceptance(A) Participant2,3,4 Signature Acceptance(A) Afghanistan..................................................19 Apr 1948 A Botswana .....................................................26 Feb 1975 A Albania.........................................................22 Jul 1946 26 May 1947 A Brazil ...........................................................22 Jul 1946 2 Jun 1948 A Algeria ......................................................... 8 Nov 1962 A Brunei Darussalam ......................................25 -

The United States Nuclear Weapon Program: A

DOE/ES-0005 (Draft) 67521 wees ce eee ee ee THE UNITED STATES NUCLEAR WEAPON PROGRAM: | A SUMMARYHISTORY '<) March 1983 U.S. Department of Energy Assistant Secretary, Management and Administration Office of The Executive Secretariat History Division DOE/ES-0005 (Draft) THE UNITED STATES NUCLEAR | WEAPON PROGRAM: A SUMMARY HISTORY © | « By: Roger M. Anders Archivist With: Jack M. Holl Alice L. Buck Prentice C. Dean March 1983 U.S. Department of Energy Assistant Secretary, Management and Administration Office of The Executive Secretariat History Division Washington, D.C. 20585 The Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977 brought together for the first time in one department most of the Federal Government's energy programs. With these programs came a score of organizational entities, each with its owm history and traditions, from a dozen depart- ‘ments and independent agencies. The History Division has prepared a series of pamphlets on The Institutional Origins of the Department of Energy. Each pamphlet explains the history, goals, and achievements of @ predecessor agency or a major program of the Department of Energy. This pamphlet, which replaces Roger M. Anders' previous booklet cn "The Office of Military Application," traces the history of the United States nuclear weapon program from its inception during World War II to the present. Nuclear weapons form the core of America's modern defenses. anders! history describes the truly formidable efforts of «ne Atomic Energy Commission, the Energy Research and Develogment Administration, and the Departmr to create a diverse anc sophisticated arsenal of nuclear 2 accomplishments of these agencies and their plants and lak : created an “atomic shieic" which protects America today. -

Taylor University Bulletin (July 1946)

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University Taylor University Bulletin Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections 7-1-1946 Taylor University Bulletin (July 1946) Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu-bulletin Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "Taylor University Bulletin (July 1946)" (1946). Taylor University Bulletin. 269. https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu-bulletin/269 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Taylor University Bulletin by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. '*1aulcit Unm^u. WVULL£TI/S^ UPLAND, INDIANA, JULY 1946 FACENG THE IMPLICATIONS OF AN INAUGURAL The President Discusses His Philosophy of Education In the April issue this year of the North Central Association Quarterly there is an article by Dr. A. J. Brum baugh entitled, "Why Be a College President?" About 100 college presi dents are inaugurated each year; and in the Association, of which Dr. Brum baugh tabulates statistics, the average life of a college president is 12 years. Olie might rightfully ask, "Had you read his article, and had you seen the precarious position which he assigns to a college president, would you have accepted this responsibility?" I think I would. And it is for that reason I want to share with you some of my thoughts which have clustered around my accept ance of a position which is reputedly one of the most hazardous, lonely, and yet strenuous jobs into which a man may pour his life.