Reaching Critical Mass 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Number Document Title Authors, Compilers, Or Editors Date

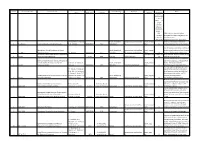

Authors, Compilers, or Date (M/D/Y), Location, Site, or Format/Copy/C Ensure Index # Document Number Document Title Status Markings Keywords Notes Editors (M/Y) or (Y) Company ondition Availability Codes: N=ORNL/NCS; Y=NTIS/ OSTI, J‐ 5700= Johnson Collection‐ ORNL‐Bldg‐ 5700; T‐ CSIRC= ORNL/ Nuclear Criticality Safety Thomas Group,865‐574‐1931; NTIS/OSTI is the Collection, DOE Information LANL/CSIRC. Bridge:http://www.osti.gov/bridge/ J. W. Morfitt, R. L. Murray, Secret, declassified computational method/data report, original, Early hand calculation methods to 1 A‐7.390.22 Critical Conditions in Cylindrical Vessels G. W. Schmidt 01/28/1947 Y‐12 12/12/1956 (1) good N estimate process limits for HEU solution Use of early hand calculation methods to Calculation of Critical Conditions for Uranyl Secret, declassified computational method/data report, original, predict critical conditions. Done to assist 2 A‐7.390.25 Fluoride Solutions R. L. Murray 03/05/1947 Y‐12 11/18/1957 (1), experiment plan/design good N design of K‐343 solution experiments. Fabrication of Zero Power Reactor Fuel Elements CSIRC/Electroni T‐CSIRC, Vol‐ Early work with U‐233, Available through 3 A‐2489 Containing 233U3O8 Powder 4/1/44 ORNL Unknown U‐233 Fabrication c 3B CSIRC/Thomas CD Vol 3B Contains plans for solution preparation, Outline of Experiments for the Determination of experiment apparatus, and experiment the Critical Mass of Uranium in Aqueous C. Beck, A. D. Callihan, R. Secret, declassified report, original, facility. Potentially useful for 4 A‐3683 Solutions of UO2F2 L. Murray 01/20/1947 ORNL 10/25/1957 experiment plan/design good Y benchmarking of K‐343 experiments. -

ROCKY FLA TS PLANT HAER No

ROCKY FLA TS PLANT HAER No. C0-83 (Environmental Technology Site) Bounded by Indiana St. & Rts. 93, 128 & 72 Golden vicinity Jefferson County Colorado PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD INTERMOUNTAIN SUPPORT OFFICE - DENVER National Park Service P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD ROCKY FLATS PLANT HAER No. C0-83 (Rocky Flats Environmental Technology Site) Location: Bounded by Highways 93, 128, and 72 and Indiana Street, Golden, Jefferson County, Colorado. Date of Construction: 1951-1953 (original plant). Fabricator: Austin Company, Cleveland, Ohio. Present Owner: United States Department of Energy (USDOE). Present Use: Environmental Restoration. Significance: The Rocky Flats Plant (Plant), established in 1951, was a top-secret weapons production plant. The Plant manufactured triggers for use in nuclear weapons and purified plutonium recovered from retired weapons ( called site returns). Activities at the Plant included production, stockpile maintenance, and retirement and dismantlement. Particular emphasis was placed on production. Rocky Flats produced most of the plutonium triggers used in nuclear weapons from 1953 to 1964, and all of the triggers produced from 1964 until 1989, when production was suspended. The Plant also manufactured components for other portions of the weapons since it had the facilities, equipment, and expertise required for handling the materials involved. In addition to production processes, the Plant specialized in research concerning the properties of many materials that were not widely used in other industries, including plutonium, uranium, beryllium, and tritium. Conventional methods for machining plutonium, uranium, beryllium, and other metals were continually examined, modified, and updated in support of weapons production. -

Three Mile Island Alert Newsletters, 1980

Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections http://archives.dickinson.edu/ Three Mile Island Resources Title: Three Mile Island Alert Newsletters, 1980 Date: 1980 Location: TMI-TMIA Contact: Archives & Special Collections Waidner-Spahr Library Dickinson College P.O. Box 1773 Carlisle, PA 17013 717-245-1399 [email protected] SLAND i 1 V i Three Mile Island Alert February, 1980 Cobalt & Turkeys Collide by MikeT Klinger late Sunday evening, January 13, treatment of radiation exposure on 1-80 north of Pittsburgh, a These reports, she assured me, tractor trailer carrying radio were inaccurate. active cobalt pellets destined Alot of questions remain for use in. a NYC hospital collided unanswered. Why was the story with a trailer load of turkeys. played down so quickly? Why did On Monday morning WHP news the leaking cannister later_____ initially reported a broken cannister was emitting substantial amounts of radiation, .65 Rem/hr. to 4.0 Rem/hr.--"a major health hazard," according to Warren Bassett, administrator of nearby Brookville Hospital. WHP's coverage of the accident decreased and by mid-morning, ’ the story was no longer broadcast. A fifteen-mile stretch of 1-80 was closed off as state police waited for a DER radiation become "a crack in the trailer expert before getting close compartment"? Why was there su< to the truck. The DER expert a large discrepancy in the was stranded due to bad weather figures? Why and how did a and didn't get to the scene "major health hazard" in the until later in the day. The morning become "slight" by the initial dangerous readings of time it hit the Evening News? .65 R/hr. -

Oral History Center University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California East Bay Regional Park District Oral History Project Judy Irving: A Life in Documentary Film, EBRPD Interviews conducted by Shanna Farrell in 2018 Copyright © 2019 by The Regents of the University of California Interview sponsored by the East Bay Regional Park District Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Judy Irving dated December 6, 2018. -

It's Time to Expand Nuclear Power

Intelligence Squared U.S. 1 01/23/2020 January 23, 2020 Ray Padgett | [email protected] Mark Satlof | [email protected] T: 718.522.7171 It’s Time to Expand Nuclear Power Guests: For the Motion: Kirsty Gogan, Daniel Poneman Against the Motion: Arjun Makhijani, Gregory Jaczko Moderator: John Donvan AUDIENCE RESULTS Before the debate: After the debate: 49% FOR 47% FOR 21% AGAINST 42% AGAINST 30% UNDECIDED 11% UNDECIDED Start Time: (00:00:00) John Donvan: We have a key note conversation because the topic relates to science. Would you please welcome to the stage Bill Nye, the science guy? [applause] Bill Nye: John, so good to see you! John Donvan: Great to see you. [applause] So, that was the appropriate level of applause, I think. Bill Nye: Wow! Intelligence Squared U.S. 2 01/23/2020 John Donvan: There was a really interesting story that relates to you and Intelligence Squared that I want to start with. Bill Nye: Ah, yes. Yes. John Donvan: And you were -- you have been, in the past, a member of our audience. You've been out there. And there was one particular debate that you attended, and an interesting thing happened. Pick it up from there. Bill Nye: So, I was at a debate about genetically-modified organisms, GMOs. And -- John Donvan: The resolution was: Genetically modified food -- Bill Nye: Is good or bad. Or was necessary. John Donvan: No. It was -- it was stated as an imperative: "Genetically-modified food." It was a sentence. Bill Nye: Ah, yes. John Donvan: Okay. -

July 1979 • Volume Iv • Number Vi

THE FASTEST GROWING CHURCH IN THE WORLD by Brother Keith E. L'Hommedieu, D.D. quite safe tosay that ofall the organized religious sects on the current scene, one church in particular stands above all in its unique approach to religion. The Universal LifeChurch is the onlyorganized church in the world withno traditional religious doctrine. Inthe words of Kirby J. Hensley,founder, "The ULC only believes in what is right, and that all people have the right to determine what beliefs are for them, as long as Brother L 'Hommed,eu 5 Cfla,r,nan right ol the Board of Trusteesof the Sa- they do not interferewith the rights ofothers.' cerdotal Orderof the Un,versalL,fe andserves on the Board of O,rec- Reverend Hensley is the leader ofthe worldwide torsOf tOe fnternahOna/ Uns'ersaf Universal Life Church with a membership now L,feChurch, Inc. exceeding 7 million ordained ministers of all religious bileas well as payfor traveland educational expenses. beliefs. Reverend Hensleystarted the church in his NOne ofthese expenses are reported as income to garage by ordaining ministers by mail. During the the IRS. Recently a whole town in Hardenburg. New 1960's, he traveled all across the country appearing York became Universal Life ministers and turned at college rallies held in his honor where he would their homes into religious retreatsand monasteries perform massordinations of thousands of people at a thereby relieving themselves of property taxes, at time. These new ministers were then exempt from least until the state tries to figure out what to do. being inducted into the armed forces during the Churches enjoycertain othertax benefits over the undeclared Vietnam war. -

NEW TITLES in BIOETHICS Annual Cumulation Volume 20, 1994

NATIONAL REFERENCE CENTER FOR BIOETHICS LITERATURE THE JOSEPH AND ROSE KENNEDY INSTITUTE OF ETHICS GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, DC 20057 NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS Annual Cumulation Volume 20, 1994 (Includes Syllabus Exchange Catalog) Lucinda Fitch Huttlinger, Editor Gregory P. Cammett, Managing Editor ISSN 0361-6347 A NOTE TO OUR READERS . Funding for the purchase of the materials cited in NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS was severely reduced in September 1994. We are grateful for your donations, as well as your recom mendations to your publishers to forward review copies to the Editor. In addition to being listed here, all English-language titles accepted for the collection will be considered for inclusion in the BIOETHICSLINE database, produced at the Kennedy Institute of Ethics under contract with the National Library of Medicine. Your efforts to support this publication and the dissemination of bioethics information in general are sincerely appreciated. NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS is published four times Inquiries regarding NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS per year (quarterly) by the National Reference Center should be addressed to: for Bioethics Literature, Kennedy Institute of Ethics. Gregory Cammett, Managing Editor Annual Cumulations are published in the following year (regarding subscriptions and claims) as separate publications. NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS is a listing by subject of recent additions OR to the National Reference Center's collection. (The subject classification scheme is reproduced in full with Lucinda Fitch Huttlinger, Editor each issue; it can also be found at the end of the (regarding review copies, gifts, and exchanges) cumulated edition.) With the exception of syllabi listed NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS as part of our Syllabus Exchange program, and docu National Reference Center for Bioethics ments in the section New Publications from the Ken Literature nedy Institute of Ethics, materials listed herein are not Kennedy Institute of Ethics available from the National Reference Center. -

Reel Impact: Movies and TV at Changed History

Reel Impact: Movies and TV Õat Changed History - "Õe China Syndrome" Screenwriters and lmmakers often impact society in ways never expected. Frank Deese explores the "The China Syndrome" - the lm that launched Hollywood's social activism - and the eect the lm had on the world's view of nuclear power plants. FRANK DEESE · SEP 24, 2020 Click to tweet this article to your friends and followers! As screenwriters, our work has the capability to reach millions, if not billions - and sometimes what we do actually shifts public opinion, shapes the decision-making of powerful leaders, perpetuates destructive myths, or unexpectedly enlightens the culture. It isn’t always “just entertainment.” Sometimes it’s history. Leo Szilard was irritated. Reading the newspaper in a London hotel on September 12, 1933, the great Hungarian physicist came across an article about a science conference he had not been invited to. Even more irritating was a section about Lord Ernest Rutherford – who famously fathered the “solar system” model of the atom – and his speech where he self-assuredly pronounced: “Anyone who expects a source of power from the transformation of these atoms is talking moonshine.” Stewing over the upper-class British arrogance, Szilard set o on a walk and set his mind to how Rutherford could be proven wrong – how energy might usefully be extracted from the atom. As he crossed the street at Southampton Row near the British Museum, he imagined that if a neutron particle were red at a heavy atomic nucleus, it would render the nucleus unstable, split it apart, release a lot of energy along with more neutrons shooting out to split more atomic nuclei releasing more and more energy and.. -

Chapter 3: the Rise of the Antinuclear Power Movement: 1957 to 1989

Chapter 3 THE RISE OF THE ANTINUCLEAR POWER MOVEMENT 1957 TO 1989 In this chapter I trace the development and circulation of antinuclear struggles of the last 40 years. What we will see is a pattern of new sectors of the class (e.g., women, native Americans, and Labor) joining the movement over the course of that long cycle of struggles. Those new sectors would remain autonomous, which would clearly place the movement within the autonomist Marxist model. Furthermore, it is precisely the widening of the class composition that has made the antinuclear movement the most successful social movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Although that widening has been impressive, as we will see in chapter 5, it did not go far enough, leaving out certain sectors of the class. Since its beginnings in the 1950s, opposition to the civilian nuclear power program has gone through three distinct phases of one cycle of struggles.(1) Phase 1 —1957 to 1967— was a period marked by sporadic opposition to specific nuclear plants. Phase 2 —1968 to 1975— was a period marked by a concern for the environmental impact of nuclear power plants, which led to a critique of all aspects of nuclear power. Moreover, the legal and the political systems were widely used to achieve demands. And Phase 3 —1977 to the present— has been a period marked by the use of direct action and civil disobedience by protesters whose goals have been to shut down all nuclear power plants. 3.1 The First Phase of the Struggles: 1957 to 1967 Opposition to nuclear energy first emerged shortly after the atomic bomb was built. -

The Japanese Nuclear Power Option: What Price?

Volume 6 | Issue 3 | Article ID 2697 | Mar 03, 2008 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Japanese Nuclear Power Option: What Price? Arjun Makhijani, Endo Tetsuya The Japanese Nuclear Power Option: What particular, energy-hungry China and India- but Price? also for the region as a whole. In Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere, plans for and Endo Tetsuya and Arjun Makhijani expressions of interest in nuclear energy have been expanding. In the midst of rising oil With the price of oil skyrocketing to more than prices, expectations are growing that nuclear $100 a barrel, many nations including Japan energy will fill the gap between energy demand and the United States, are looking to the and supply. nuclear power option among others. Is nuclear power a viable option in a world of expensive In the area of global warming, the Fourth and polluting fossil fuels? Japan Focus, in the Assessment Report by the Intergovernmental first of a series of articles on energy options Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that centered on renewable options and thethe global temperature will increase by 2.4 to environmental costs of energy options, presents 6.4 degrees Celsius by the end of the 21st the case for nuclear power recently made by century if fossil-fuel dependent economic Endo Tetsuya and a critique of the nuclear growth is maintained. It is now universally option by Arjun Makhijani. recognized that the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is a matter of urgency, and necessitates seeking viable, reliable alternative sources of energy. In this sense, Atoms for the Sustainable Future:nuclear energy can be expected to contribute Utilization of Nuclear Energy as a Way to to global efforts to cope with the global Cope with Energy and Environmental warming problem as its carbon dioxide Challenges emissions are much smaller than those of fossil sources. -

Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons

VERSION: Charles P. Blair, “Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons,” in Gary Ackerman and Jeremy Tamsett, eds., Jihadists and Weapons of Mass Destruction: A Growing Threat (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2009), pp. 193-238. c h a p t e r 8 Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons Charles P. Blair CONTENTS Introduction 193 Improvised Nuclear Devices (INDs) 195 Fissile Materials 198 Weapons-Grade Uranium and Plutonium 199 Likely IND Construction 203 External Procurement of Intact Nuclear Weapons 204 State Acquisition of an Intact Nuclear Weapon 204 Nuclear Black Market 212 Incidents of Jihadist Interest in Nuclear Weapons and Weapons-Grade Nuclear Materials 213 Al-Qa‘ida 213 Russia’s Chechen-Led Jihadists 214 Nuclear-Related Threats and Attacks in India and Pakistan 215 Overall Likelihood of Jihadists Obtaining Nuclear Capability 215 Notes 216 Appendix: Toward a Nuclear Weapon: Principles of Nuclear Energy 232 Discovery of Radioactive Materials 232 Divisibility of the Atom 232 Atomic Nucleus 233 Discovery of Neutrons: A Pathway to the Nucleus 233 Fission 234 Chain Reactions 235 Notes 236 INTRODUCTION On December 1, 2001, CIA Director George Tenet made a hastily planned, clandestine trip to Pakistan. Tenet arrived in Islamabad deeply shaken by the news that less than three months earlier—just weeks before the attacks of September 11, 2001—al-Qa‘ida and Taliban leaders had met with two former Pakistani nuclear weapon scientists in a joint quest to acquire nuclear weapons. Captured documents the scientists abandoned as 193 AU6964.indb 193 12/16/08 5:44:39 PM 194 Charles P. Blair they fled Kabul from advancing anti-Taliban forces were evidence, in the minds of top U.S. -

Could Asian Nuclear War Radioactivity Reach North America

Institute for Energy and Environmental Research For a safer, healthier environment and the democratization of science Could Asianhttp://ieer.org Nuclear War Radioactivity Reach North America? (Earthfiles Interview with Arjun Makhijani) © 2002 by Linda Moulton Howe Reporter and Editor, Earthfiles.com Red arrow points at India and Pakistan on opposite side of the world from Canada and the United States. The Marshall Islands where the U. S. experimented in the 1950swith many atomic tests is at the far left in the Pacific Ocean. From Marshall Island and Nevada Test Site nuclear explosions, radioactive fallout riding on the prevailing westerly winds reached North Carolina and New York, distances nearly equivalent to the 10,000 to 12,000 miles India and Pakistan are from the west coast of the United States. June 4, 2002 Takoma Park, Maryland – If India and Pakistan strike each other with Hiroshima-sized bombs, how much radioactivity could reach the atmosphere and fall out around the world? That is a question I began asking a week ago and discovered that very little is known about the consequences downwind of such a catastrophe. The National Atmospheric Release Advisory Center (NARAC) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California seemed like it should know. NARAC’s public affairs office describes its “primary function is to support the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Department of Defense (DOD) for radiological releases.” But when I asked an page 1 / 7 Institute for Energy and Environmental Research For a safer, healthier environment and the democratization of science informationhttp://ieer.org officer there for information about the spread of radioactivity in the atmosphere from a nuclear war in Asia, the answer was, “That information is classified in the interests of national security.” One scientist who wants to talk about potential radioactive fallout and its threat to earth life is Arjun Makhijani, Ph.D., President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IEER) in Tacoma Park, Maryland.