HARAAD REEB (Quenching the Thirst) II FINAL REPORT October 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afmadow District Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia

Afmadow district Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia Introduction Location map The Detailed Site Assessment (DSA) was triggered in the perspectives of different groups were captured2. KI coordination with the Camp Coordination and Camp responses were aggregated for each site. These were then Management (CCCM) Cluster in order to provide the aggregated further to the district level, with each site having humanitarian community with up-to-date information on an equal weight. Data analysis was done by thematic location of internally displaced person (IDP) sites, the sectors, that is, protection, water, sanitation and hygiene conditions and capacity of the sites and the humanitarian (WASH), shelter, displacement, food security, health and needs of the residents. The first round of the DSA took nutrition, education and communication. place from October 2017 to March 2018 assessing a total of 1,843 sites in 48 districts. The second round of the DSA This factsheet presents a summary of profiles of assessed sites3 in Afmadow District along with needs and priorities of took place from 1 September 2018 to 31 January 2019 IDPs residing in these sites. As the data is captured through assessing a total of 1778 sites in 57 districts. KIs, findings should be considered indicative rather than A grid pattern approach1 was used to identify all IDP generalisable. sites in a specific area. In each identified site, two key Number of assessed sites: 14 informants (KIs) were interviewed: the site manager or community leader and a women’s representative, to ensure Assessed IDP sites in Afmadow4 Coordinates: Lat. 0.6, Long. -

Enhanced Enrolment of Pastoralists in the Implementation and Evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia

Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia Prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute UNICEF ESARO JUNE 2013 Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia © United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Nairobi, 2013 UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) PO Box 44145-00100 GPO Nairobi June 2013 The report was prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the policies or the views of UNICEF. The text has not been edited to official publication standards and UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this publication do not imply an opinion on legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. For further information, please contact: Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, University of Basel: [email protected] Eugenie Reidy, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Dorothee Klaus, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Cover photograph © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-2301/Kate Holt 2 Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Protection Cluster Update Weekly Report

Protection Cluster Update Funded by: The People of Japan Weeklyhttp://www.shabelle.net/article.php?id=4297 Report 23 th September 2011 European Commission IASC Somalia •Objective Protection Monitoring Network (PMN) Humanitarian Aid This update provides information on the protection environment in Somalia, including apparent violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law as reported during the last two weeks through the IASC Somalia Protection Cluster monitoring systems. Incidents mentioned in this report are not exhaustive. They are intended to highlight credible reports in order to inform and prompt programming and advocacy initiatives by the humanitarian community and national authorities. General Overview Heavy fighting in southern regions between Al Shabaab and Transitional Federal Government (TFG) has led to heightened protection concerns throughout the reporting period. In Ceel Waaq, 43 people were killed and almost 80 wounded and an unknown number displaced following fighting between the TFG and Al Shabaab forces.1 The civilian population continues to face insecurity due to the ongoing conflict compounded by limited access to basic services and humanitarian support. In other regions, the famine has continued to take its toll on the Somali population. This week the United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) stated that Somalia has the worst international mortality rate for children. 2 Furthermore, local sources in the district of Eldher town, Galgaduud region reported that 30 people had died as a result of starvation and -

AWDAL REGION - Borama District

p AWDAL REGION - Borama District 42°45'E 43°0'E 43°15'E N N ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 0 0 1 LUGHAYE 1 ZEYLAC Ali Gala(P28-001) ! Dabo Dilaac(Q28-001) ! Fiqi Aadan(R27-001) ! Caro-Wareen(R30-001) ! Xariirad(S19-001) ! Ceel Dacar Jif(S26-001) Fadhi Aroor-Seel(S20-001) Baxay(S22-001) Budhuq(S24-001) ! ! ! ! Fadhiwanag(S29-002) Xun(S29-001) Dhagaxa ! ! Gor Madow(T27-001) Ali-Heley(T27-002) Dhoobo(T28-002) Goray(T25-001) ! ! ! Baki ! (!! Weeraar(T28-001) ! N Darya N ' ' 5 Dheere(T20-001) 5 ! 1 1 ° ° 0 Dix-Gudban(U24-001) BORAMA 0 Gargoorey(U24-002) !! 1 1 Xalimaale(V25-001) ! Boon(V24-001) ! Badanbed(V28-001) ! Hagoogane(V30-001) ! Daray Culaacule(W23-002) !Beden ! Quruxsan(W28-001) Cabaasa(W23-003) Bed(W28-002) Dhidhiid(W23-001) ! Abaase ! Dhadheer(W27-001) ! Abasse ! Xamarta Gaagaab(X27-002) ! Cabaasa(X28-001) Dur-Dur Cad(X30-001) BAKI ! Qolqol(X24-001) Cadaad(X27-001) ! ! Wanbarta ! Ciye(X25-002) Quljed(X23-001) ! ! Qolqol(X25-001) ! Cara-Cad(Y24-002) Cadaad(Y28-001) !! Dibriyo Maleh Xeego(Y28-002) Hego (Maraaley)(Y24-003) Jirjir(Y24-001) ! Baki(Y28-003) Nadhi(Y27-001) Maraalay, ! Shakal(Y30-001) !Abakor Maraaley(Z23-001) Cadaawe(Z30-001) ! ! Taw Sheikh Tawle(Z27-001) ! Huways(Z25-001) Dibrio N ! Ando N ' Meleh(Z26-001) ' 0 ! Bait(A28-001) 0 ° ! ° 0 0 1 Fulin-Fulka(A25-002) 1 ! Dagmo!-Laqas(A24-001) ! Sattawa(A25-001) Cara-Ga!ranug(A26-001) ! ! ! Daray-Macaane(A27-001) Tuur-Qaylo(A26-002) ! Tawtawle(A27-002) Fa!dhi-Cad(A28-002) ! Waraabe Dhammuug(B27-004) Fadhi ! ! Camuud(B27-001) Dareeray(B26-001) ! Xun(A29-001) Xasan ! Badhiile(B25!-004) Sog-Sogley(B25-003) -

Somalia Nutrition Cluster Geo-Tagging: Capacity Assessment

Somalia Nutrition Cluster Geo-tagging: Capacity Assessment Somalia Nutrition Cluster Geo-tagging: Capacity Assessment This report was written by Forcier Consulting for the Somali Nutrition Cluster. About the Somali Nutrition Cluster The Somali Nutrition Cluster (SNC) has been operational in Somalia since 2006, following the United Nation’s Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) recommendations of activating the cluster system to effectively coordinate the humanitarian partner’ work. The vision of SNC is to safeguard and improve the nutritional status of emergency-affected populations in Somalia. Led by UNICEF, the SNC consists of a network of about 100 part- ners, 80 per cent of which are national NGOs, mostly based in central and southern regions of Somalia. Its core purpose is to enable cluster-wide stakeholders and sub-national coordination mechanisms to have all the necessary capacity to achieve timely, quality and appropriate nutrition responses to emergencies. Twitter: @Nutrition_Som About Forcier Consulting Forcier Consulting was founded in response to the overwhelming demand for data, research and information in some of the most challenging environments in Africa. While we aim to produce reliable and high-quality research in these complex settings, we also make long-term invest- ments in building the capacity of national staff to serve as researchers and consultants. www.forcierconsulting.com/ Legal Notice and Disclaimer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means with- out prior approval in writing from Forcier Consulting and the Somalia Nutrition Cluster. This report is not a legally binding document. -

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki District 2 Awdal Region Borama District 3 Awdal Region Lughaya District 4 Awdal Region Zeila District 5 Bakool Region El Barde District 6 Bakool Region Hudur District 7 Bakool Region Rabdhure District 8 Bakool Region Tiyeglow District 9 Bakool Region Wajid District 10 Banaadir Region Abdiaziz District 11 Banaadir Region Bondhere District 12 Banaadir Region Daynile District 13 Banaadir Region Dharkenley District 14 Banaadir Region Hamar Jajab District 15 Banaadir Region Hamar Weyne District 16 Banaadir Region Hodan District 17 Banaadir Region Hawle Wadag District 18 Banaadir Region Huriwa District 19 Banaadir Region Karan District 20 Banaadir Region Shibis District 21 Banaadir Region Shangani District 22 Banaadir Region Waberi District 23 Banaadir Region Wadajir District 24 Banaadir Region Wardhigley District 25 Banaadir Region Yaqshid District 26 Bari Region Bayla District 27 Bari Region Bosaso District 28 Bari Region Alula District 29 Bari Region Iskushuban District 30 Bari Region Qandala District 31 Bari Region Ufayn District 32 Bari Region Qardho District 33 Bay Region Baidoa District 34 Bay Region Burhakaba District 35 Bay Region Dinsoor District 36 Bay Region Qasahdhere District 37 Galguduud Region Abudwaq District 38 Galguduud Region Adado District 39 Galguduud Region Dhusa Mareb District 40 Galguduud Region El Buur District 41 Galguduud Region El Dher District 42 Gedo Region Bardera District 43 Gedo Region Beled Hawo District www.downloadexcelfiles.com 44 Gedo Region El Wak District 45 Gedo -

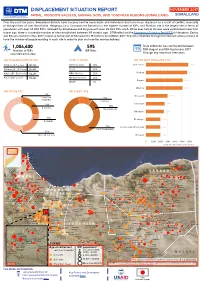

Somaliland Displacement Profile November 2017.Pdf

DISPLACEMENT SITUATION REPORT NOVEMBER 2017 AWDAL, WOQOOYI GALBEED, SANAAG, SOOL AND TOGDHEER REGIONS (SOMALILAND) SOMALILANDSOMALIA Over the past few years, Somaliland districts have become host to households and individuals that have been displaced as a result of conflict, insecurity or drought from all over Somaliland. Hargeysa, Laas Caanood and Borama has the highest number of IDPs, and Stadium site is the largest site in terms of population with over 34,000 IDPs, followed by Statehouse and Erigavo with over 25,000 IDPs each. While over half of all sites were established more than a year ago, there is a sizeable number of sites established between 1-9 months ago . DTM rolled out the Emergency Tracking Tool (ETT) in Hargeysa, Zeylac and Borama district in May 2017 scaled up to the rest of Somaliland’s 19 districts by October 2017. The data collected through this tool will allow partners to have the number of people residing in each site in order to plan and monitor service delivery. 1,004,400 595 Data collection was conducted between Number of IDPs IDP Sites 18th August and 18th September 2017 (rounded estimates) through key informant interviews AGE DISAGGREGATION OF IDPS PRIORITY NEEDS TOP TEN MOST POPULATED SITES * Children (0-5 years) 181,916 Drinking water 18% Children (6 - 18 Years) 269,431 Food 30% Adults (18 - 59 Years) 342,206 NFIs /Shelter 21% Elders (60+ years) 102,442 Medical services 24% WASH 7% AGE OF THE SITE IDP SITE BY TYPE 2% Less than 13% 3 months Planned 23% 10% 6 months Spontaneous 24% 9 months 77% Host Community -

World Health Organisation Horn of Africa Initiative

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION HORN OF AFRICA INITIATIVE REPORT ON VISIT TO HARGEISA, SOMALILAND, FOR PLANNING THE SECOND PHASE OF THE INITIATIVE 5 – 12 FEBRUARY 2002 Dr Abdullahi M. Ahmed Coordinator, Horn of Africa Initiative Addis Ababa, 2002 A. BACKGROUND Somaliland has borders with Djibouti and the Somali Region of Ethiopia. In the first phase of the Horn of Africa Initiative (HOAI), Hargeisa district was involved in the cross border collaboration with both countries. Cross-Border Health Committees (CBHCs) were established and joint activities were organized. Capacity building, in terms of provision of equipment and instruments, training in management and control of communicable diseases, were also implemented. The workshops and trainings, organized by the HOAI attended by the health managers and professionals were: · Management and planning workshop for HOAI Focal Persons and Programme Managers · Standardisation of treatment protocols of common communicable diseases · Training in TB management and transfer of patients across the border. · Training in Malaria management · Laboratory training in TB and Malaria diagnosis The current assignment is part of first round of visits to the member countries of the Horn in order to brief the Ministries of Health about the Initiative objectives and to start the planning process of phase two, taking into consideration lessons learned in the first phase of the Initiative. Moreover, in December 2001, a consultation meeting on health as bridge for peace (HBP) was held in Sharma Sheikh, Egypt. Ministry of Health and WHO Somalia attended the meeting. Delegates from Somalia requested WHO technical assistance regarding strengthening health services and health professionals associations and exchange of information among the regions. -

FSNAU Quarterly Brief, December 2018

FSNAU Food Security Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit - Somalia & Nutrition Issued December 22, 2018 Quarterly Brief - Focus on 2018 Post-Deyr Season Early Warning According to the consensus forecast from Greater Horn of Africa Climate outlook KEY Forum (GHACOF50) issued at the end of August 2018, there was a greater likelihood of normal to above normal 2018 Deyr (October – December) rains ISSUES across Somalia. Above-average Deyr rains were also expected to cause flooding in flood-prone low-lying and riverine livelihoods of the country. However, actual Deyr season rainfall between October and early December 2018 turned out to be below average in most parts of the country. Livestock holdings among poor pastoral households in northeastern and central Somalia remain below baseline. Livestock body conditions, reproduction and milk production and availability are below average Climate to poor in areas that received below average Deyr rains. With few saleable animals, poor pastoralists will not be able to meet their food needs, payback accumulated debt and cover increased expenditure Civil on water during the forthcoming dry Jilaal (January – March 2019) season. Insecurity In Northwest Agropastoral livelihood zone, the 2018 Gu/Karan cereal harvest was estimated at 11 000 tonnes. This is 43 percent lower than the amount projected in July 2018 and 76 percent lower compared Livestock to the Gu/Karan average cereal production for 2011 – 2017. Main reasons for poor production are below average and poorly distributed Gu/Karan rains, dry spells, pest infestation and bird attacks. Agriculture Due to below average rainfall amounts and its poor temporal and spatial distribution during the current Deyr season, the overall cereal harvest in southern Somalia is expected to be 30-40 percent below the Markets long-term average. -

'The Evils of Locust Bait': Popular Nationalism During the 1945 Anti-Locust Control Rebellion in Colonial Somaliland

‘THE EVILS OF LOCUST BAIT’: POPULAR NATIONALISM DURING THE 1945 ANTI-LOCUST CONTROL REBELLION IN COLONIAL SOMALILAND I Since the 1960s, students of working-class politics, women’s his- tory, slave resistance, peasant revolts and subaltern nationalism have produced a rich and global historiography on the politics of popular classes. Except for two case studies, popular politics have so far been ignored in Somali studies, yet anti-colonial nationalism was predominantly popular from the beginning of colonial rule in 1884, when Great Britain conquered the northern Somali coun- try, the Somaliland Protectorate (see Map).1 The British justified colonial conquest as an educational enterprise because the Somalis, as Major F. M. Hunt stated, were ‘wild’, ‘violent’, ‘uncivilised’, without any institutions or government; hence the occupation of the country was necessary to begin the task of ‘educating the Somal in self-government’.2 The Somalis never accepted Britain’s self-proclaimed mission. From 1900 to 1920, Sayyid Muhammad Abdulla Hassan organized a popular rural- based anti-colonial movement.3 From 1920 to 1939, various anti- colonial resistance acts were carried out in both the rural and urban areas, such as the 1922 tax revolt in Hargeysa and Burao, 1 This article is based mainly on original colonial sources and Somali poetry. The key documents are district weekly reports sent to the secretary to the government, and then submitted to the Colonial Office. These are the ‘Anti-Locust Campaign’ reports, and I include the reference numbers and the dates. I also use administrative reports, and yearly Colonial Office reports. All original sources are from the Public Record Office, London, and Rhodes House Library, Oxford, England. -

Pillars of Peace Somali Programme

PILLARS OF PEACE SOMALI PROGRAMME Democracy in Somaliland Challenges and Opportunities Hargeysa, November 2010 PILLARS OF PEACE Somali Programme Democracy in Somaliland: Challenges and Opportunities Hargeysa, November 2010 i Pillars of Peace - Somali Programme Democracy in Somaliland: Challenges and Opportunities APD Hargeysa, Somaliland Tel: (+252 2) 520 304 Email: [email protected] http://www.apd-somaliland.org APD Burco, Somaliland Phone: (+252-2) 712 980/ 81/ 82 Email: [email protected] http://www.apd-somaliland.org “This report was produced by the Academy for Peace and Development and Interpeace and represents exclusively their own views. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the contributing donors and should not be relied upon as a statement of the contributing donors or their services. The contributing donors do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor do they accept responsibility for any use made thereof.” Pillars of Peace - Somali Programme ii Acknowledgements The Academy would first and foremost like to sincerely thank the people of Somaliland, whose constant engagement and attentive participation made this publication possible. It would be terribly unfair for their efforts to go unacknowledged. Equally important, the Academy is grateful to the government of Somaliland whose dedicated support and endless commitment throughout the research process was of particularly constructive value. The publication of this research could not have been possible without the dedicated efforts of the Friends of the Academy, a close-knit group upon whose unrelenting encouragement and patronage APD is greatly indebted to. The Academy would also like to acknowledge the efforts of its support staff in the Administrative/ Finance Department as well as the Culture and Communication Department. -

Rebuilding Confidence on Land Issues in Somalia”

i Baseline Survey on “Rebuilding Confidence on Land Issues in Somalia” Baseline Survey on “Rebuilding Confidence on Land Issues in Somalia” ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgement v Executive summary 1 1. Introduction 2 1.1. Land issues in Somalia 2 1.2. Study overview and objectives 4 1.2. 1. Scope of the study 5 2. Methodology 12 2.1. Approach 6 2.2. Field phase 6 2.3. Study sites 6 2.4. Sampling procedures 6 2.4.1. Household survey 6 2.4.2. Key Informant Interviews 7 2.4.3. Focus Group Discussions 7 2.5. Sample size 7 2.5.1. Household survey 7 2.5.2. Key Informant Interviews 7 2.5.3. Focus Group Discussions 7 2.6. Data collection 8 2.6.1. Training of field teams 8 2.6.2. Household interviews 8 2.6.3. Focus Group Discussions 8 2.6.4. Key Informant Interviews 9 2.7. Data management and analysis 9 3. Characteristics of sampled households 10 3.1. Household characteristics 10 3.2. Household composition 10 3.3. Household food compositionby district, gender and livelihood 14 3.4. Social Safety Nets 15 3.5 Employment 16 3.6 Household Enterprise: Proportion of households owning private businesses 17 4. Land Indicators 18 4.1. Access to the land use 18 4.1.1. Crop farming 19 4.1.2. Livestock keeping 20 4.2. Land tenure 22 4.3. Land acquisition 24 4.4. Land rights 26 4.5. Land size 28 4.6. Land conflicts 29 4.7.