Sittwe Camp Profiling Report 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Report to the People on the Progress of the Implementation of Recommendations on Rakhine State (January to April 2018)

Report to the People on the Progress of the Implementation of Recommendations on Rakhine State (January to April 2018) Introduction As the Government of Myanmar works towards achieving stability, durable peace and development across the country including Rakhine State, the Committee for Implementation of the Recommendations on Rakhine State was established with an aim to help create a peaceful, fair and prosperous future for the people living in the State. This report provides an update to the people of Myanmar regarding the progress of the implementation by the Committee, for the period of January to April 2018. Economic and Social Development Due compensations are granted for lands acquired from local people for projects necessary for comprehensive development of Rakhine State. Compensations for 6.06 acres of land that was acquired for Kantharyar police station in Gwa Township amounting in 2.7068 million MMK, and for 3.11 acres of acquired for Ahmyintkyun police station in Sittwe Township amounting in 7.775 million MMK are now sanctioned; and authorities are currently processing the payments to the farmers. Compensation for the land acquired for the village tract administrator office of Ahmyintkyun Village Tract in Sittwe Township is included in the FY 2018-19 budget proposal. China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC) and the Government Designated Entity (GOE) as a counterpart from Myanmar are working closely for conducting Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), Social Impact Assessment (SIA) and Geological and Topographical (G.T) Survey for Kyaukpyu Special Economic Zone Project, in order to promote public participation, and to ensure local people can enjoy the benefits from investments and extraction of natural resource in Rakhine State. -

Education Assistance to Children in Rakhine State

Education Assistance to Children in Rakhine State Jan – June 2015 Issue No. 01/2015 A quarterly newsletter published by LWF — a project funded by European Union's Education programme for "Myanmar" The project is funded by the European Union, co- LWF Myanmar holds Project Launching funded by Church of Sweden and implemented by The Ceremony for Education Assistance to Lutheran World Federation in collaboration with Children in Rakhine State respective Township Education Offices, Rakhine State Education Department. On 4th February 2015, LWF Myanmar launched the EU Education project, in Sittwe Township, Rakhine Well-experienced Trainers provide Teaching State to inform the project activities and modalities of Methodologies and Lesson Planning Training implementation and to be transparent and accountable to the stakeholders. With the financial support from the European Union, the LWF Myanmar, Rakhine Project provided a 5 day Training on Teaching Methodologies and Lesson Planning for government school teachers in 4 townships; Sittwe, Pauk Taw, Mrauk U and Ann during May. The aim is to improve the quality of teaching and learning in formal schools. The training was provided to a total of 84 (64 female) teachers from 8 government schools and facilitated by the lecturers, who used to be trainers and lectures of Education University, and are currently working in th EU Education Project Launching Ceremony in Sittwe on 4 Myanmar Literacy and Resource Center (MLRC), in 1 February 2015 Yangon. A total of 109 attendees included 6 people from local The training provided by LWF was a refresher on media, the Chief Minister of Rakhine State, the teaching methodologies and lesson training. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

Where There Is Police, There Is Persecution Government Security

Physicians for Where There is Police, Human Rights There is Persecution Government Security Forces and October 2016 Human Rights Abuses in Myanmar’s Northern Rakhine State An immigration officer inspects Rohingyas’ paperwork at a checkpoint in Rakhine State. About Physicians for Human Rights For 30 years, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has used science and medicine to document and call attention to mass atrocities and severe human rights violations. PHR is a global organization founded on the idea that health professionals, with their specialized skills, ethical duties, and credible voices, are uniquely positioned to stop human rights violations. PHR’s investigations and expertise are used to advocate for persecuted health workers and medical facilities under attack, prevent torture, document mass atrocities, and hold those who violate human rights accountable. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Introduction This report was written by Claudia Rader edited and Widney Brown, Physicians for prepared the report for 4 Methodology Human Rights (PHR) program publication. director, and is based on field 6 Background research conducted from November PHR would like to acknowledge 2015 to May 2016 in Myanmar the Bangladesh-based research 8 Findings (Rakhine State and Yangon) and team who contributed to the Bangladesh. study, design, and data collection 20 Discussion and also reviewed and edited the The report benefited from review report. PHR would also like to 24 Conclusion and by PHR leadership and staff, thank other external reviewers Recommendations including DeDe Dunevant, director who wish to remain anonymous. of communications, Donna McKay, 27 Endnotes MS, executive director, Marianne PHR is deeply indebted to the Møllmann, LLM, MSc, senior Rohingya and Rakhine people researcher, and Claudia Rader, MS, who were willing to share their content and marketing manager. -

Appeals Humanitarian Appeal for Rakhine in Myanmar – MMR171

APPEAL Humanitarian Appeal for Rakhine, Myanmar MMR171 Appeal Target: US$ 1,512,360 Balance requested: US$ 1,512,360 "We are isolated in theseIDP centers. We get some support but the shelters and toilets are inadequate, we don't have enough food, or medicine, the children don't have the school supplies they need and the youth and able bodied men and women sit idle with no livelihood opportunities." Mr. U Zaw Min living with 5 family members (2 school aged children), Kaung Doke 1 IDP Camp, Sittwe, Rakhine SECRETARIAT: 150, route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100, 1211 Geneva 2, Switz. TEL.: +4122 791 6434 – FAX: +4122 791 6506 – www.actalliance.org Humanitarian Appeal for Rakhine in Myanmar – MMR171 Table of contents 1. Project Summary Sheet 2. BACKGROUND 2.1. Context 2.2. Needs 2.3. Capacity to Respond 2.4. Core Faith Values (+/-) 3. PROJECT RATIONALE 3.1. Intervention Strategy and Theory of Change 3.2. Impact 3.3. Outcomes 3.4. Outputs 3.5. Preconditions / Assumptions 3.6. Risk Analysis 3.7. Sustainability / Exit Strategy 3.8. Building Capacity of National Members (+/-) 4. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 4.1. ACT Code of Conduct 4.2. Implementation Approach 4.3. Project Stakeholders 4.4. Field Coordination 4.5. Project Management 4.6. Implementing Partners 4.7. Project Advocacy 4.8. Private/Public sector co-operation (+/-) 4.9. Engaging Faith Leaders (+/-) 5. PROJECT MONITORING 5.1. Project Monitoring 5.2. Safety and Security Plans 5.3. Knowledge Management 6. PROJECT ACCOUNTABILITY 6.1. Mainstreaming Cross-Cutting Issues 6.1.1. Gender Marker / GBV (+/-) 6.1.2. -

DRC Myanmar Poverty and Hunger Alleviation Through

DRC Myanmar│ Poverty and Hunger Alleviation through Support, Empowerment, and Increased Networking (PHASE IN II) via the European Union PROJECT SNAPSHOT │ Community-driven Development in Sittwe Township of Rakhine State Bringing communities out of isolation and closer to each other and to markets is one of the keys to development in Myanmar’s Rakhine state to create access, break the poverty cycle and strengthen resilience. DRC’s Community-driven Development project in Rakhine is one such approach that aims to empower individuals and entire communities. Infrastructure is the overall theme for these types of projects that are designed and implemented by DRC with communities in rural areas. The community decides In close collaboration with key stakeholders, committed citizens and community representatives, DRC introduces participatory processes to develop ideas and plans for local infrastructure projects. These can be linked to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), Disaster Risk Reduction (DDR), food security or community cohesion. The needs are identified and prioritised collectively through the establishment of Village Development Committees to ensure local ownership and social cohesion. The committees are composed to reflect age, gender and diversity in each community, to ensure that men and women, of different ages, across the community are heard and involved. Roads Since 2018, DRC has worked with five villages in Aung Daing, in Sittwe Township of Rakhine State. A rapid needs assessment made it clear that new roads were their key priority as the villages all suffer from isolation due to roads that are old or damaged by seasonal floods. Road construction was eventually were carried out in three Rohingya villages using macadam engineering, and concrete road construction in two other Rakhine villages. -

MYANMAR, RAKHINE STATE: COVID-19 Situation Report No

MYANMAR, RAKHINE STATE: COVID-19 Situation Report No. 08 1 September 2020 This report, which focuses on the recent surge in COVID-19 cases in Rakhine, is produced by OCHA Myanmar covering the period of 10 to 31 August, in collaboration with Inter-Cluster Coordination Group and wider humanitarian partners. The next report will be issued on or around 18 September. HIGHLIGHTS • A total of 393 locally transmitted cases have been reported across Rakhine between 16 August and 1 September, bringing to 409 the number of cases in 16 townships since 18 May. Across the country, 887 cases, six fatalities and 354 recoveries have been reported. • The recent surge in local transmission includes COVID-19 positive cases among the personnel of the United Nations agencies and international non-governmental organizations (INGO). • No cases have been reported in camps or sites for internally displaced people (IDPs) as of 31 August, while displaced persons who had been in contact with COVID-19 confirmed cases were placed in quarantine and tested. • Sittwe General Hospital, where most COVID-19 confirmed cases are being treated, remains the primary treatment facility for Rakhine. Efforts to increase treatment capacities continue. • The Rakhine State Government has introduced various COVID-19 measures since 16 August, including a state-wide “stay-at-home” order and other measures aimed at preventing the local transmission. • Humanitarian actors are assessing the impact of the recently introduced COVID-19 measures on operations, including COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. SITUATION OVERVIEW 409 16 393 887 157K Cases in Rakhine Townships Locally transmitted Cases countrywide Total tests conducted countrywide SURGE IN LOCAL TRANSMISSION: Since 16 August, when the Ministry of Health and Sports (MoHS) confirmed a new COVID-19 case in Sittwe - the first case of local transmission reported in almost a month country-wide - the number of locally transmitted cases has continued to increase in Rakhine State. -

Draft Restricted

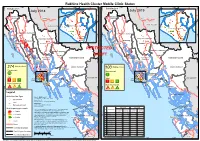

Rakhine Health Cluster Mobile Clinic Status N N N N ' ' ' ' 0 0 92°30'E 93°0'E 93°30'E 0 92°30'E 93°0'E 93°30'E 0 3 3 3 3 ° ° ° ° 1 1 Bangladesh 1 Bangladesh 1 2 2 July 2018 2 July 2019 2 MAUNGDAW MAUNGDAW TOWNSHIP Paletwa TOWNSHIP Paletwa CHIN STATE CHIN STATE SITTWE TOWNSHIP SITTWE TOWNSHIP BUTHIDAUNG TOWNSHIP N N N N ' ' ' BUTHIDAUNG TOWNSHIP ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° ° ° 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 KYAUKTAW TOWNSHIP KYAUKTAW TOWNSHIP Buthidaung Sittwe Buthidaung Sittwe Maungdaw Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw RESTRICTED MRAUK-U TOWNSHIP MRAUK-U TOWNSHIP Mrauk-U DRAFT Mrauk-U RATHEDAUNG RATHEDAUNG PONNAGYUN PONNAGYUN TOWNSHIP RAKHINE STATE TOWNSHIP RAKHINE STATE N TOWNSHIP N N TOWNSHIP N ' ' ' ' 0 0 0 0 3 Rathedaung 3 3 Rathedaung 3 ° ° ° ° 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 2 Mobile clinics MINBYA TOWNSHIP Mobile clinics MINBYA TOWNSHIP Minbya 274 Ponnagyun Minbya 100 Ponnagyun Government Government 116 PAUKTAW PAUKTAW TOWNSHIP 1 TOWNSHIP Joint ANN TOWNSHIP SITTWE Joint SITTWE ANN TOWNSHIP Pauktaw Pauktaw TOWNSHIP TOWNSHIP 7 6 4 Sittwe Sittwe 1 4 5 Non Government Non Government N N N N ' Myebon ' ' Myebon ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° ° ° 0 81 39 12 0 0 0 2 2 2 54 21 8 2 Legend MYEBON TOWNSHIP MYEBON TOWNSHIP Clinic Provider Type Map ID: MIMU1546v04 Creation Date: 17 September 2019 Government Paper Size: A3 Joint Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Data Source: Non-Government Health Cluster (Rakhine State) Base map: MIMU Visit frequency per month July 2018 July 2019 Clinics not displayed in the maps because of missing geographic No Township Mobile Vistits/ Mobile Vistits/ < 4 visits coordinates: 9 locations in 2018 and 6 locations in 2019 N N N Clinics Month Clinics Month N ' Place Names: General Administration Department (GAD) and field ' ' ' 0 0 0 0 3 sources.Place names on this product are in line with the general 3 3 3 ° ° ° 1 Sittwe 92 404 56 328 ° 9 4 - 8 visits cartographic practice to reflect the names of such places as 9 9 9 1 KYAUKPYU TOWNSHIP 1 1 2 Buthidaung 64 85 6 8 KYAUKPYU TOWNSHIP 1 designated by the government concerned. -

A Background to the Security Crisis in Northern Rakhine

ISSUE: 2017 No. 79 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 23 October 2017 A Background to the Security Crisis in Northern Rakhine Ye Htut* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • On 25 August 2017, the day after Kofi Annan’s Rakhine Advisory Commission submitted its report, the Rohingya group ARSA simultaneously attacked 30 police outposts and one army regiment’s headquarters. The Myanmar Army responded with a massive security operation that led to more than 500,000 Rohingya people fleeing to Bangladesh. • Rakhine State has had a history of Muslim separatist movements since 1948, and successive governments have tried to control illegal immigration and prevent separatist movements in Northern Rakhine State. In 2004, the removal of military intelligence chief General Khin Nyunt weakened the Myanmar government’s intelligence network in Rakhine State, and in 2013, the security situation worsened when the Border and Immigration Control Command was disbanded. • Without these two security apparatuses, the government lacked intelligence on separatist sentiments and illegal operations in Northern Rakhine State, and security forces were caught off-guard by the ARSA attacks in October 2016 and August 2017. • The current humanitarian crisis, the breakdown of law and order, and the communal violence and hatred in Northern Rakhine State are not only a legacy of the past but also contemporary developments that are seeing the emergence of a new terrorist group with extremist links. * Ye Htut is Visiting Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute and former Information Minister of Myanmar. 1 ISSUE: 2017 No. 79 ISSN 2335-6677 BACKGROUND1 Concurrent with Burma’s independence negotiations with the the United Kingdom, Muslims in the Buthidaung-Maungdaw area of Northern Arakan2 in Burma had appealed to what was then East Pakistan (today’s Bangladesh) to annex these areas. -

Overview of the February 2019 3W RAKHINE State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Overview of the February 2019 3W RAKHINE State The MIMU 3W gathers inputs from participating humanitarian and development agencies on Who is doing What, Where, across Myanmar. It is conducted every 6 months and provides information on agencies’ activities at various levels (village/village tract/township and IDP camps). 225 agencies participated in the February 2019 3W, providing information on their humanitarian and development activities across 22 sectors and 154 sub-sectors as defined by technical/sector working groups. 3W reporting is quite comprehensive for projects of INGO, UN and Red Cross agencies, but there is under-reporting of activities of local NGOs and CBOs since not all are participating. Agencies must report to a sufficiently detailed level (village or camp level) for their work to be reflected fully in the MIMU 3W products. This Overview of the Rakhine 3W results describes projects under implementation as of February 28, 2019. Further information on planned and recently completed projects is available from the 3W dataset, published on the MIMU website. Projects under implementation can also be viewed in our interactive dashboards - 3W Township Dashboard, 3W Village Tract Dashboard, and the 3W Technical Assistance Dashboard. 1. Organizations active in Rakhine State In total, 72 agencies reported activities in Rakhine state: 60 are engaged in Development focused projects (749 village tracts/towns), 19 are engaged in support to other vulnerable groups (not IDP related, 225 village tracts/towns), 20 are engaged in activities which target IDPs and Host Communities (126 village tracts/towns and 47 camps) and 10 are active in IDP-only focused activities (25 village tracts/towns and 43 camps). -

Public Health Information Officer

Fact Sheet 2009 Myanmar Public Health & HIV UNHCR Operational Area Total Population of Concern 850,594 Bangladesh Northern Rakhine State [map] Tu tCh au ng In T u L a h M Ca h La h Day Ph att Under-fives children 160,631 a Ba uk Shu Ph wa iYa h u Ye Au ng Sa n Yah Ph wa i n Ky au n g Na Pha y g H lain g T h i B Kh a Mo u n g Z e ik d u ∗ a Ng a r Yan tCh au ng N a n Y a r Ga n g Th it Hto n e Na h K h w a S o n e 185,902 t Women of reproductive age K ha Ma u ng Ch au ng w h Ta Ma n T h a r i B a D a Ga r Ye Na uk NgN ar Th ar d Me e T ik e Th e tK a in e N y a r a Ta un g Pyo Le tYa h o T au ng Py o L et W e P a D a K h a Da iW a h N a h Li u r P a D a K h a W y a T h it t Tin Ma y n K wa n T h iP in K ya un g Tau ng Lo ng Do ne 600000other 504,061 h M in Gy iY wa g T he Ch au ng W e d K y e in Ky un Pa uk Sa n K a r P in Y in La ke Ya h Ky u n Pa u k Sin Oh N Ta Ra Gu Au n g Se ik P y in K yu n Pau k Py u Su Ky a uk Ch au ng My o Mi Ch a u n g o Go a tP i My aw Ch au ng Ky ein Ch au ng r L ou nd Do ne Ze e Bin Ch au ng t Ye T win Py in S a Pa iKo n e 500000 Ah tet P y e u Ma h D oe Ta n Pa n Bai Cha un g Nga r Sar Ky eu P y u e H ma Ka Ny in Ta n Ku p Pa Gou ng Z ee Do n My o T h it Y in Ma Kya un g T a un g K y e tYo e P y in Ng a r Khu Ya East Rakhine T au ng Ba za ar Ya y Mye tTa un g Ng an Ch au ng Th in Ga N e t Oo Sh a iK y a A ur a Ma P win tHp yu Ch au ng C h a n P y in Ba Da Na r A ye Ra Cha K ya r Gou ng Ta u ng Inn Ch au ng Mya w T au ng Ya iTw in Ky u n Ph ur W u tCh au ng Y ai Khu tCh au ng Kh wa So n Me e Gya un g Z ay