Mosque As Monument: the Afterlives of Jama Masjid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RSIS COMMENTARIES RSIS Commentaries Are Intended to Provide Timely And, Where Appropriate, Policy Relevant Background and Analysis of Contemporary Developments

29/2010 RSIS COMMENTARIES RSIS Commentaries are intended to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy relevant background and analysis of contemporary developments. The views of the authors are their own and do not represent the official position of the S.Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced electronically or in print with prior permission from RSIS. Due recognition must be given to the author or authors and RSIS. Please email: [email protected] or call 6790 6982 to speak to the Editor RSIS Commentaries, Yang Razali Kassim. __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Darul Uloom Deoband: Stemming the Tide of Radical Islam in India Taberez Ahmed Neyazi 10 March 2010 Maulana Mahmood Madani of Jamiat Ulema-i-Hind with Yoga guru Baba Ramdev at Deoband The growing threat of terrorism can be checked with the help of influential religious organisations and seminaries. The recent active involvement of Darul Uloom Deoband of India at the civil society level to build up movement against terrorism has yielded positive result. It is a strategy that can be replicated in other parts of the world. AFTER THE killing of 13 people by Army psychiatrist Major Nidal Malik Hasan at Fort Hood in Texas, Thomas Friedman wrote in the New York Times on 28 November 2009 asking Muslims to present the real Islam before the world. “Whenever something like Fort Hood happens you say, ‘This is not Islam.’ I believe that. But you keep telling us what Islam isn’t. You need to tell us what it is and _________________________________________________________________________________ S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU, South Spine, Block S4, Level B4, Nanyang Avenue, Singapore 639798. -

Conflict Between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict

Conflict between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict Conflict between India and Pakistan Peter Lyon Conflict in Afghanistan Ludwig W. Adamec and Frank A. Clements Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia John B. Allcock, Marko Milivojevic, and John J. Horton, editors Conflict in Korea James E. Hoare and Susan Pares Conflict in Northern Ireland Sydney Elliott and W. D. Flackes Conflict between India and Pakistan An Encyclopedia Peter Lyon Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright 2008 by ABC-CLIO, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lyon, Peter, 1934– Conflict between India and Pakistan : an encyclopedia / Peter Lyon. p. cm. — (Roots of modern conflict) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57607-712-2 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-57607-713-9 (ebook) 1. India—Foreign relations—Pakistan—Encyclopedias. 2. Pakistan-Foreign relations— India—Encyclopedias. 3. India—Politics and government—Encyclopedias. 4. Pakistan— Politics and government—Encyclopedias. I. Title. DS450.P18L86 2008 954.04-dc22 2008022193 12 11 10 9 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Production Editor: Anna A. Moore Production Manager: Don Schmidt Media Editor: Jason Kniser Media Resources Manager: Caroline Price File Management Coordinator: Paula Gerard This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. -

THE HINDU EDITORIAL on a VARANASI COURT ORDERING an ASI SURVEY in GYANVAPI MOSQUE Relevant For: Null | Topic: Indian Architecture Incl

Source : www.thehindu.com Date : 2021-04-10 A DISTURBING ORDER: THE HINDU EDITORIAL ON A VARANASI COURT ORDERING AN ASI SURVEY IN GYANVAPI MOSQUE Relevant for: null | Topic: Indian Architecture incl. Art & Craft & Paintings The order of a civil court in Varanasi that the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) should conduct a survey to ascertain whether the Gyanvapi mosque was built over a demolished Hindu temple is an unconscionable intervention that will open the floodgates for another protracted religious dispute. The order, apparently in gross violation of the explicit legislative prohibition on any litigation over the status of places of worship, is likely to give a fillip to majoritarian and revanchist forces that earlier carried on the Ram Janmabhoomi movement over a site in Ayodhya. That dispute culminated in the country’s highest court handing over the site to the very forces that conspired to illegally demolish the Babri Masjid. The plaintiffs, who have filed a suit as representatives of Hindu faith to reclaim the land on which the mosque stands, have now succeeded in getting the court to commission an ASI survey to look for the sort of evidence that they would never have been able to adduce on their own. The order has been issued despite the fact that the Allahabad High Court reserved its order on the maintainability of the suit on March 15 and is yet to pronounce its ruling. It is not clear why the civil judge did not wait for the ruling and went ahead with his directive to the ASI. By an order in 1997, the civil court had decided that the suit was not barred by the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which said all pending suits concerning the status of places of worship will abate and that none can be instituted. -

Modi Promise to Build a Bridge Even Where There Is No River

C M Y K K ASHMIR Beware of Pig Fat in Your Food 5 29 Muharram | 1436 Hijri | Vol: 17 | Issue: 241 | Pages : 08 | Price: `3 www.kashmirobserver.net SUNDAY 23 NOVEMBER 2014 / SRINAGAR TODAY: MOSTLY CLOUDY MAXIMUM: 15OC / MINIMUM: -2OC / HUMIDITY : 65% / SUNSETS TODAY... 05:24 PM / SUNRISES TOMORROW... 07.09 AM WISDOM Politicians are the same all over. They Will Fulfil Vajpayee’s Dream: Modi promise to build a bridge even where there is no river. ■ ‘Have deep affection from the core of my heart and soul for Kashmir’ ...........Nikita Khrushchev ■ ‘Two families have looted J&K in successive turns’ Observer News Service ment, development and develop- ment,” he said, adding “I will re- KISHTWAR: Asserting that he turn your trust in me with interest Two Families Did Not Loot: Omar Poll Vehicle has deep affection for Kashmir, by ensuring full fledged develop- Prime Minister Narendra Modi ment in J&K.” SRINAGAR: Rejecting the allegations by Prime Minister Modi that Mishap Kills 1 Saturday vowed to fulfil the He said his wish is to complete two political families have “looted” Jammu and Kashmir, Chief SRINAGAR: A man was killed on “dream” of former PM Atal Bihari the work started by Vajpayee. “It Minister Omar Abdullah asked him to tell what his government Saturday and 10 others were in- Vajpayee based on “democracy, is my wish and I will come repeat- has found to prove this in its six months in office. jured when a vehicle turned turtle humanity and Kashmiriyat” that edly here for that,” the Prime Min- “You have been in the government for the last six months at the during an election campaign in has made a “special place” in the ister said amid slogans of ‘Modi, Centre. -

Debasishdas SUNDIALS to TELL the TIMES of PRAYERS in the MOSQUES of INDIA January 1, 2018 About

Authior : DebasishDas SUNDIALS TO TELL THE TIMES OF PRAYERS IN THE MOSQUES OF INDIA January 1, 2018 About It is said that Delhi has almost 1400 historical monuments.. scattered remnants of layers of history, some refer it as a city of 7 cities, some 11 cities, some even more. So, even one is to explore one monument every single day, it will take almost 4 years to cover them. Narratives on Delhi’s historical monuments are aplenty: from amateur writers penning down their experiences, to experts and archaeologists deliberating on historic structures. Similarly, such books in the English language have started appearing from as early as the late 18th century by the British that were the earliest translation of Persian texts. Period wise, we have books on all of Delhi’s seven cities (some say the city has 15 or more such cities buried in its bosom) between their covers, some focus on one of the cities, some are coffee-table books, some attempt to create easy-to-follow guide-books for the monuments, etc. While going through the vast collection of these valuable works, I found the need to tell the city’s forgotten stories, and weave them around the lesser-known monuments and structures lying scattered around the city. After all, Delhi is not a mere necropolis, as may be perceived by the un-initiated. Each of these broken and dilapidated monuments speak of untold stories, and without that context, they can hardly make a connection, however beautifully their architectural style and building plan is explained. My blog is, therefore, to combine actual on-site inspection of these sites, with interesting and insightful anecdotes of the historical personalities involved, and prepare essays with photographs and words that will attempt to offer a fresh angle to look at the city’s history. -

Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ANNUAL Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 © Gandhi and People Gathering by Shri Upendra Maharathi Mahatma Gandhi by Shri K.V. Vaidyanath (Courtesy: http://ngmaindia.gov.in/virtual-tour-of-bapu.asp) (Courtesy: http://ngmaindia.gov.in/virtual-tour-of-bapu.asp) ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti ANNUAL REPORT - 2019-2020 Contents 1. Foreword ...................................................................................................................... 03 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 05 3. Structure of the Samiti.................................................................................................. 13 4. Time Line of Programmes............................................................................................. 14 5. Tributes to Mahatma Gandhi......................................................................................... 31 6. Significant Initiatives as part of Gandhi:150.................................................................. 36 7. International Programmes............................................................................................ 50 8. Cultural Exchange Programmes with Embassies as part of Gandhi:150......................... 60 9. Special Programmes..................................................................................................... 67 10. Programmes for Children............................................................................................. -

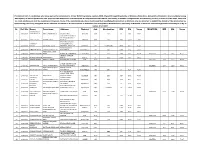

Provisional List of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to 2

Provisional List of candidates who have applied for admission to 2-Year B.Ed.Programme session-2020 offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir. Any candidate having discrepancy in his/her particulars can approach the Directorate of Admissions & Competitive Examinations, University of Kashmir alongwith the documentary proof by or before 31-07-2021, after that no claim whatsoever shall be considered. However, those of the candidates who have mentioned their Qualifying Examination as Masters only are directed to submit the details of the Graduation by approaching personally alongwith all the relevant documnts to the Directorate of Admission and Competitive Examinaitons, University of Kashmir or email to [email protected] by or before 31-07-2021 Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO %age MASTERS MM MO %age SHARIQ RAUOF 1 20610004 AHMAD MALIK ABDUL AHAD MALIK QASBA KHULL KULGAM RBA BSC 10 6.08 60.80 VPO HOTTAR TEHSILE BILLAWAR DISTRICT 2 20610005 SAHIL SINGH BISHAN SINGH KATHUA KATHUA RBA BSC 3600 2119 58.86 BAGHDAD COLONY, TANZEELA DAWOOD BRIDGE, 3 20610006 RASSOL GH RASSOL LONE KHANYAR, SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM BCOMHONS 2400 1567 65.29 KHAWAJA BAGH 4 20610008 ISHRAT FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMAD DAR BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM BSC 1800 912 50.67 MOHAMMAD SHAFI 5 20610009 ARJUMAND JOHN WANI PANDACH GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM BSC 1800 899 49.94 MASTERS 700 581 83.00 SHAKAR CHINTAN 6 20610010 KHADIM HUSSAIN MOHD MUSSA KARGIL KARGIL ST BSC 1650 939 56.91 7 20610011 TSERING DISKIT TSERING MORUP -

Modernity, Locality and the Performance of Emotion in Sufi Cults

EMBODYING CHARISMA Emerging often suddenly and unpredictably, living Sufi saints practising in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are today shaping and reshaping a sacred landscape. By extending new Sufi brotherhoods and focused regional cults, they embody a lived sacred reality. This collection of essays from many of the subject’s leading researchers argues that the power of Sufi ritual derives not from beliefs as a set of abstracted ideas but rather from rituals as transformative and embodied aesthetic practices and ritual processes, Sufi cults reconstitute the sacred as a concrete emotional and as a dissenting tradition, they embody politically potent postcolonial counternarrative. The book therefore challenges previous opposites, up until now used as a tool for analysis, such as magic versus religion, ritual versus mystical belief, body versus mind and syncretic practice versus Islamic orthodoxy, by highlighting the connections between Sufi cosmologies, ethical ideas and bodily ritual practices. With its wide-ranging historical analysis as well as its contemporary research, this collection of case studies is an essential addition to courses on ritual and religion in sociology, anthropology and Islamic or South Asian studies. Its ethnographically rich and vividly written narratives reveal the important contributions that the analysis of Sufism can make to a wider theory of religious movements and charismatic ritual in the context of late twentieth-century modernity and postcoloniality. Pnina Werbner is Reader in Social Anthropology at Keele University. She has published on Sufism as a transnational cult and has a growing reputation among Islamic scholars for her work on the political imaginaries of British Islam. Helene Basu teaches Social Anthropology at the Institut für Ethnologie in Berlin. -

Sdissfinal 4

Abstract CHATTERJEE, SUDESHNA. Children’s Friendship with Place: An Exploration of Environmental Child Friendliness of Children’s Environments in Cities. (Under the direction of Prof. Robin C. Moore.) The Child Friendly Cities is a concept for making cities friendly for all children especially in UN member countries that have ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (i.e., all except the United States) through municipal action. This idea is particularly important for improving the quality of life of poor urban children who are most affected by sweeping changes brought about by globalization and rapid urbanization in the developing nations of the global South. However, there is no theoretical understanding of a construct such as environmental child friendliness that could guide planning and design of child friendly environments in cities. Resulting from an integrative review of a large body of interdisciplinary literature, a new six- dimensional construct based on children’s friendship needs, called children’s place friendship, is proposed as underpinning environmental child friendliness from an environment-behavior perspective. The study disaggregates the idea of the child friendly city into numerous interlocking child friendly places that children themselves consider friendly based on their own experiences. These child friendly places support the six dimensions of place friendship in different ways: care and respect for places, meaningful exchange with places, learning and competence through place experience, creating and controlling territories, having secret places, and freedom of expression in places. An in-depth analytic ethnography was conducted in a low-income, high-density, mixed-use neighborhood in New Delhi, India, with children in their middle-childhood to validate and elaborate this conceptual framework. -

Continuity and Change in a Muslim Community

A Modern History of the Ismailis The Institute of Ismaili Studies The Institute of Ismaili Studies Ismaili Heritage Series, 13 General Editor: Farhad Daftary _______________________________________________________________________ Previously published titles: 1. Paul E. Walker, Abū Yaʽqūb al-Sijistānī: Intellectual Missionary (1996) 2. Heinz Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning (1997) 3. Paul E. Walker, Ḥamīd al-Dīn al-Kirmānī: Ismaili Thought in the Age of al-Ḥākim (1999) 4. Alice C. Hunsberger, Nasir Khusraw, The Ruby of Badakhshan: A Portrait of the Persian Poet, Traveller and Philosopher (2000) 5. Farouk Mitha, Al-Ghazālī and the Ismailis: A Debate on Reason and Authority in Medieval Islam (2001) 6. Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment: The Ismaili Devotional Literature of South Asia (2002) 7. Paul E. Walker, Exploring an Islamic Empire: Fatimid History and its Sources (2002) 8. Nadia Eboo Jamal, Surviving the Mongols: Nizārī Quhistānī and the Continuity of Ismaili Tradition in Persia (2002) 9. Verena Klemm, Memoirs of a Mission: The Ismaili Scholar, Statesman and Poet al-Muʼayyad fi’l-Dīn al-Shīrāzī (2003) 10. Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria (2005) 11. Sumaiya A. Hamdani, Between Revolution and State: The Path to Fatimid Statehood, Qadi al-Nuʽman and the Construction of Fatimid Legitimacy (2006) 12. Farhad Daftary, Ismailis in Medieval Muslim Societies (2005) The Institute of Ismaili Studies A Modern History of the Ismailis Continuity and Change in a Muslim Community Edited by Farhad Daftary The Institute of Ismaili Studies I.B.Tauris Publishers london • new york in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies London, 2011 Published in 2011 by I.B.Tauris & Co. -

20Years of Sahmat.Pdf

SAHMAT – 20 Years 1 SAHMAT 20 YEARS 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements 2 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 YEARS, 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements © SAHMAT, 2009 ISBN: 978-81-86219-90-4 Rs. 250 Cover design: Ram Rahman Printed by: Creative Advertisers & Printers New Delhi Ph: 98110 04852 Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust 29 Ferozeshah Road New Delhi 110 001 Tel: (011) 2307 0787, 2338 1276 E-mail: [email protected] www.sahmat.org SAHMAT – 20 Years 3 4 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 Years 5 Safdar Hashmi 1954–1989 Twenty years ago, on 1 January 1989, Safdar Hashmi was fatally attacked in broad daylight while performing a street play in Sahibabad, a working-class area just outside Delhi. Political activist, actor, playwright and poet, Safdar had been deeply committed, like so many young men and women of his generation, to the anti-imperialist, secular and egalitarian values that were woven into the rich fabric of the nation’s liberation struggle. Safdar moved closer to the Left, eventually joining the CPI(M), to pursue his goal of being part of a social order worthy of a free people. Tragically, it would be of the manner of his death at the hands of a politically patronised mafia that would single him out. The spontaneous, nationwide wave of revulsion, grief and resistance aroused by his brutal murder transformed him into a powerful symbol of the very values that had been sought to be crushed by his death. Such a death belongs to the revolutionary martyr. 6 PUBLICATIONS Safdar was thirty-four years old when he died. -

Judgment RJB-BM

1 4251 123 3rd Cent. BC 185 124 Pre-Mauryan 184 125 3rd Cent. BC 185 126 3rd Cent. B.C. 176 That there are a large number discrepancies also in the description of these Terracotta finds, which also create doubts upon the bonafides of the A.S.I. Team giving such incorrect descriptions. It is true that when archaeological deposits are disturbed, it is not surprising to find earlier material in later levels. This happens when construction or leveling activities require the bringing in of soil from peripheral areas or the clearing and mixing of older deposits. On the other hand, the reverse is impossible, that is we cannot, in an earlier stratified context, find material of later periods. However, the latter appears to be the case at Ayodhya in the context of terracotta figurines as seen in the tabulation provided on pp. 174-203. We find in numerous cases figurines of later periods in far earlier levels, as is evident from the following Table:- Table of Discrepancies in stratigraphy in relation to terracotta figurines Artefact details Discrepancies S. No. 50 R. No. 1027. Layer 2 below Floor 2 belongs to Part of human figurine. Medieval period. It is impossible Mughal level. G5, for a Medieval period layer to layer 2, below Floor 2 have material from Mughal period which is later S. No. 52 R. No. 393. Layer 5 in E8 is Post Gupta (7th - Animal figurine. Late 10th centuries AD). It is Medieval period. E8, impossible for late medieval layer 5 (Mughal) period material to be found in an earlier period.