Pollinator and Insect/Mite Management in Annona Spp.1 Daniel Carrillo, Jorge E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recolecta De Artrópodos Para Prospección De La Biodiversidad En El Área De Conservación Guanacaste, Costa Rica

Rev. Biol. Trop. 52(1): 119-132, 2004 www.ucr.ac.cr www.ots.ac.cr www.ots.duke.edu Recolecta de artrópodos para prospección de la biodiversidad en el Área de Conservación Guanacaste, Costa Rica Vanessa Nielsen 1,2, Priscilla Hurtado1, Daniel H. Janzen3, Giselle Tamayo1 & Ana Sittenfeld1,4 1 Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio), Santo Domingo de Heredia, Costa Rica. 2 Dirección actual: Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica. 3 Department of Biology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA. 4 Dirección actual: Centro de Investigación en Biología Celular y Molecular, Universidad de Costa Rica. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Recibido 21-I-2003. Corregido 19-I-2004. Aceptado 04-II-2004. Abstract: This study describes the results and collection practices for obtaining arthropod samples to be stud- ied as potential sources of new medicines in a bioprospecting effort. From 1994 to 1998, 1800 arthropod sam- ples of 6-10 g were collected in 21 sites of the Área de Conservación Guancaste (A.C.G) in Northwestern Costa Rica. The samples corresponded to 642 species distributed in 21 orders and 95 families. Most of the collections were obtained in the rainy season and in the tropical rainforest and dry forest of the ACG. Samples were obtained from a diversity of arthropod orders: 49.72% of the samples collected corresponded to Lepidoptera, 15.75% to Coleoptera, 13.33% to Hymenoptera, 11.43% to Orthoptera, 6.75% to Hemiptera, 3.20% to Homoptera and 7.89% to other groups. -

Lepidoptera Sphingidae:) of the Caatinga of Northeast Brazil: a Case Study in the State of Rio Grande Do Norte

212212 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 59(4), 2005, 212–218 THE HIGHLY SEASONAL HAWKMOTH FAUNA (LEPIDOPTERA SPHINGIDAE:) OF THE CAATINGA OF NORTHEAST BRAZIL: A CASE STUDY IN THE STATE OF RIO GRANDE DO NORTE JOSÉ ARAÚJO DUARTE JÚNIOR Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Departamento de Sistemática e Ecologia, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 58059-900, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] AND CLEMENS SCHLINDWEIN Departamento de Botânica, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Av. Prof. Moraes Rego, s/n, Cidade Universitária, 50670-901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil. E-mail:[email protected] ABSTRACT: The caatinga, a thorn-shrub succulent savannah, is located in Northeastern Brazil and characterized by a short and irregular rainy season and a severe dry season. Insects are only abundant during the rainy months, displaying a strong seasonal pat- tern. Here we present data from a yearlong Sphingidae survey undertaken in the reserve Estação Ecológica do Seridó, located in the state of Rio Grande do Norte. Hawkmoths were collected once a month during two subsequent new moon nights, between 18.00h and 05.00h, attracted with a 160-watt mercury vapor light. A total of 593 specimens belonging to 20 species and 14 genera were col- lected. Neogene dynaeus, Callionima grisescens, and Hyles euphorbiarum were the most abundant species, together comprising up to 82.2% of the total number of specimens collected. These frequent species are residents of the caatinga of Rio Grande do Norte. The rare Sphingidae in this study, Pseudosphinx tetrio, Isognathus australis, and Cocytius antaeus, are migratory species for the caatinga. -

Orchid Floral Fragrances and Their Niche in Conservation

Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 THE SCENT OF A GHOST Orchid Floral Fragrances and Their Niche in Conservation James J. Sadler WHAT IS FLORAL FRAGRANCE? It is the blend of chemicals emitted by a flower to attract pollinators. These chemicals sometimes cannot be detected by our nose. 1 Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 WHY STUDY FLORAL FRAGRANCE? Knowing the floral compounds may help improve measures to attract specific pollinators, increasing pollination and fruit-set to augment conservation. Chemical compounds can be introduced to increase pollinator density. FLORAL FRAGRANCE: BACKGROUND INFORMATION 90 plant families worldwide have been studied for floral fragrance, especially the Orchidaceae6 > 97% of orchid species remain unstudied7 Of all plants studied so far, the 5 most prevalent compounds are: limonene (71%), (E)-β-ocimene (71%), myrcene (70%), linalool (70%), and α-pinene (67%)6 2 Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 POSSIBLE POLLINATORS BEES Found to pollinate via mimicry POSSIBLE POLLINATORS WASPS Similar as bees 3 Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 POSSIBLE POLLINATORS FLIES Dracula spp. produce a smell similar to fungus where the eggs are laid POSSIBLE POLLINATORS MOTHS Usually white, large and fragrant at night 4 Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 CASE STUDY The Ghost Orchid State Endangered1 Dendrophylax lindenii THE GHOST ORCHID Range: S Florida to Cuba Epiphyte of large cypress domes and hardwood hammocks Often affixed to pond apple or pop ash Leafless Flowers May-August 5 Florida -

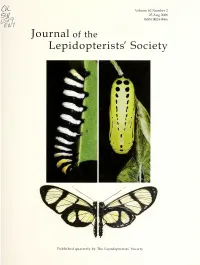

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society

Volume 62 Number 2 25 Aug 2008 ISSN 0024-0966 Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society Published quarterly by The Lepidopterists' Society ) ) THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY Executive Council John H. Acorn, President John Lill, Vice President William E. Conner, Immediate Past President David D. Lavvrie, Secretary Andre V.L. Freitas, Vice President Kelly M. Richers, Treasurer Akito Kayvahara, Vice President Members at large: Kim Garwood Richard A. Anderson Michelle DaCosta Kenn Kaufman John V. Calhoun John H. Masters Plarry Zirlin Amanda Roe Michael G. Pogue Editorial Board John W. Rrovvn {Chair) Michael E. Toliver Member at large ( , Brian Scholtens (Journal Lawrence F. Gall ( Memoirs ) 13 ale Clark {News) John A. Snyder {Website) Honorary Life Members of the Society Charles L. Remington (1966), E. G. Munroe (1973), Ian F. B. Common (1987), Lincoln P Brower (1990), Frederick H. Rindge (1997), Ronald W. Hodges (2004) The object of The Lepidopterists’ Society, which was formed in May 1947 and formally constituted in December 1950, is “to pro- mote the science of lepidopterology in all its branches, ... to issue a periodical and other publications on Lepidoptera, to facilitate the exchange of specimens and ideas by both the professional worker and the amateur in the field; to secure cooperation in all mea- sures” directed towards these aims. Membership in the Society is open to all persons interested in the study of Lepidoptera. All members receive the Journal and the News of The Lepidopterists’ Society. Prospective members should send to the Assistant Treasurer full dues for the current year, to- gether with their lull name, address, and special lepidopterological interests. -

Southwestern Rare and Endangered Plants: Proceedings of the Fourth

Conservation Implications of Spur Length Variation in Long-Spur Columbines (Aquilegia longissima) CHRISTOPHER J. STUBBEN AND BROOK G. MILLIGAN Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, New Mexico 88003 ABSTRACT: Populations of long-spur columbine (Aquilegia longissima) with spurs 10-16 cm long are known only from a few populations in Texas, a historical collection near Baboquivari Peak, Arizona, and scattered populations in Coahuila, Chihuahua, and Nuevo Leon, Mexico. Populations of yellow columbine with spurs 7-10 cm long are also found in Arizona, Texas, and Mexico, and are now classified as A. longissima in the recent Flora of North America. In a multivariate analysis of floral characters from 11 yellow columbine populations representing a continuous range of spur lengths, populations with spurs 10-16 cm long are clearly separate from other populations based on increasing spur length and decreasing petal and sepal width. The longer-spurred columbines generally flower after monsoon rains in late summer or fall, and occur in intermittently wet canyons and steep slopes in pine-oak forests. Also, longer-spurred flowers can be pollinated by large hawkmoths with tongues 9-15 cm long. Populations with spurs 7-10 cm long cluster with the common golden columbine (A. chrysantha), and may be the result of hybridization between A. chrysantha and A. longissima. Uncertainty about the taxonomic status of intermediates has contributed to a lack of conservation efforts for declining populations of the long-spur columbine. The genus Aquilegia is characterized are difficult to identify accurately in by a wide diversity of floral plant keys. For example, floral spurs morphologies and colors that play a lengths are a key character used to major role in isolating two species via differentiate yellow columbine species in differences in pollinator visitation or the Southwest. -

Peña & Bennett: Annona Arthropods 329 ARTHROPODS ASSOCIATED

Peña & Bennett: Annona Arthropods 329 ARTHROPODS ASSOCIATED WITH ANNONA SPP. IN THE NEOTROPICS J. E. PEÑA1 AND F. D. BENNETT2 1University of Florida, Tropical Research and Education Center, 18905 S.W. 280th Street, Homestead, FL 33031 2University of Florida, Department of Entomology and Nematology, 970 Hull Road, Gainesville, FL 32611 ABSTRACT Two hundred and ninety-six species of arthropods are associated with Annona spp. The genus Bephratelloides (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae) and the species Cerconota anonella (Sepp) (Lepidoptera: Oecophoridae) are the most serious pests of Annona spp. Host plant and distribution are given for each pest species. Key Words: Annona, arthropods, Insecta. RESUMEN Doscientas noventa y seis especies de arthrópodos están asociadas con Annona spp. en el Neotrópico. De las especies mencionadas, el género Bephratelloides (Hyme- noptera: Eurytomidae) y la especie Cerconota anonella (Sepp) (Lepidoptera: Oecopho- ridae) sobresalen como las plagas mas importantes de Annona spp. Se mencionan las plantas hospederas y la distribución de cada especie. The genus Annona is confined almost entirely to tropical and subtropical America and the Caribbean region (Safford 1914). Edible species include Annona muricata L. (soursop), A. squamosa L. (sugar apple), A. cherimola Mill. (cherimoya), and A. retic- ulata L. (custard apple). Each geographical region has its own distinctive pest fauna, composed of indigenous and introduced species (Bennett & Alam 1985, Brathwaite et al. 1986, Brunner et al. 1975, D’Araujo et al. 1968, Medina-Gaud et al. 1989, Peña et al. 1984, Posada 1989, Venturi 1966). These reports place emphasis on the broader as- pects of pest species. Some recent regional reviews of the status of important pests and their control have been published in Puerto Rico, U.S.A., Colombia, Venezuela, the Caribbean Region and Chile (Medina-Gaud et al. -

Two Large Tropical Moths (Thynartia Zenobia (Noctuidae) and Cocytiuns

VOLUME 53, NUMBER 3 129 VALLEE, G. & R. BEIQUE. 1979. Degilts d'une bepiaJe et Satyridae) and Burnet moths (Zygaena, Zygaenidae) from susceptihilite des peupliers. Phytoprotection 60:23- 30. temperate environments. In H.V Danks (ed.), Insect life-cycle WAGNER, D. L. & J. ROSOVSKY 1991. Mating systems in primitive polymorphism. Theory, evolution and ecological consequences Lepidopte ra, with emphasis on the reproductive behaviour of for seasonality and diapause control. Kluwer Academic Korscheltellus gracilis (Hepialidae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands. 378 pp. 102:277- 303. WAGNER, D. L., D. R. TOB!, B. L. PARKER, W. E. WALLNER & J. G. B. CHRISTIAN SCHMIDT, 208 - 10422 78 Ave., Edmonton, Alberta, LEONARD. 1989. Immature stages and natural enemies of CANADA T6E lP2, DAVlD D. LAWRIE , .301 - 10556 84 Ave., Korscheltellus gracilis (Lepidoptera: Hepialidae). Ann. Edmonton, Alberta, CANADA T6E 2H4. Entomol. Soc. Am. 82:717-724. WINN, A. F. 1909. The Hepialidae, or Ghost-moths. Can. Entomol. Received for publication 5 April 1999; revised and accepted 9 41:189-193. December 1999. WU'KI NG, W. & c. MENGELKOCH. 1994. Control of alternate-year flight activities in high-alpine Ringlet butterflies (Erebia, journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 53(3 ), 1999, 129- 130 TWO LARGE TROPICAL MOTHS (THYSANIA ZENOBIA (NOCTUIDAE) AND COCYTlUS ANTAEUS (SPHINGIDAE)) COLONIZE THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS Additional key words: light traps, island colonization. The arrival and establishment of a species OIl an isolated oceanic (kerosene lamps) and collections made by amateur entomologists. island is a relatively rare event. The likelihood of colonization Recently (1989 and 1992), Bernard Landry carried out an intensive depends on a variety of fcatures of the species, including dispersal Lepidoptera survey on the islands but he never collected the species ability, availability of food (hostplants or prey) and ability to (Landry pers. -

Moths: Lepidoptera

Moths: Lepidoptera Vítor O. Becker - Scott E. Miller THE FOLLOWING LIST summarizes identi- Agency, through grants from the Falconwood fications of the so-called Macrolepidoptera Corporation. and pyraloid families from Guana Island. Methods are detailed in Becker and Miller SPHINGIDAE (2002). Data and illustrations for Macrolepi- doptera are provided in Becker and Miller SPHINGINAE (2002). Data for Crambidae and Pyralidae will Agrius cingulatus (Fabricius 1775). United States be provided in Becker and Miller (in prepara- south to Argentina. tion). General, but outdated, background infor- Cocytius antaeus (Drury 1773). Southern United mation on Crambidae and Pyralidae are pro- States to Argentina. vided by Schaus (1940). Data for Pterophoridae Manduca sexta (Linnaeus 1763). Widespread in are provided in Gielis (1992) and Landry and the New World. Gielis (1992). Author and date of description Manduca rustica (Fabricius 1775). Widespread in are given for each species name. Earlier dates the New World. were not always printed on publications; those Manduca brontes (Drury 1773). Antilles north to in square brackets indicate that the year was Central Florida. determined from external sources not the pub- lication itself As in previous lists, authors' MACROGLOSSINAE names are put in parentheses when their Pseudosphinx tetrio (Linnaeus 1771). (See plate generic placement has been revised. Detailed 37.) United States through the Antilles to acknowledgments are provided in Becker and Argentina. Miller (2002), but, in addition, we are espe- Erinnyis alope (Drury 1773). Widespread in the cially grateful to C. Gielis, E.G. Munroe, M. New World. Shaffer, and M. A. Solis for assistance with iden- Erinnyis ello (Linnaeus 1758). Neotropical. -

Check List 4(2): 123–136, 2008

Check List 4(2): 123–136, 2008. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Light-attracted hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) of Boracéia, municipality of Salesópolis, state of São Paulo, Brazil. Marcelo Duarte 1 Luciane F. Carlin 1 Gláucia Marconato 1, 2 1 Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo. Avenida Nazaré 481, Ipiranga, CEP 04263-000, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Curso de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Zoologia), Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo. Rua do Matão, travessa 14, número 321. CEP 05508-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Abstract: The light-attracted hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) of the Estação Biológica de Boracéia, municipality of Salesópolis, state of São Paulo, Brazil were sampled during a period of 64 years (1940-2004). A total of 2,064 individuals belonging to 3 subfamilies, 6 tribes, 23 genera and 75 species were identified. Macroglossinae was the most abundant and richest subfamily in the study area, being followed by Sphinginae and Smerinthinae. About 66 % of the sampled individuals were assorted to the macroglossine tribes Dilophonotini and Macroglossini. Dilophonotini (Macroglossinae) was the richest tribe with 26 species, followed by Sphingini (Sphinginae) with 18 species, Macroglossini (Macroglossinae) with 16 species, Ambulycini (Smerinthinae) and Philampelini (Macroglossinae) with seven species each one, and Acherontiini (Sphinginae) with only one species. Manduca Hübner (Sphinginae) and Xylophanes Hübner (Macroglossinae) were the dominant genera in number of species. Only Xylophanes thyelia thyelia (Linnaeus) and Adhemarius eurysthenes (R. Felder) were recorded year round Introduction Hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) comprise Kitching 2002). Because of their capability to fly about 200 genera and 1300 species (Kitching and far away, these moths are potential long distance Cadiou 2000). -

Infestation of Sphingidae (Lepidoptera)

Infestation of Sphingidae (Lepidoptera) by otopheidomenid mites in intertropical continental zones and observation of a case of heavy infestation by Prasadiseius kayosiekeri (Acari: Otopheidomenidae) V. Prasad To cite this version: V. Prasad. Infestation of Sphingidae (Lepidoptera) by otopheidomenid mites in intertropical con- tinental zones and observation of a case of heavy infestation by Prasadiseius kayosiekeri (Acari: Otopheidomenidae). Acarologia, Acarologia, 2013, 53 (3), pp.323-345. 10.1051/acarologia/20132100. hal-01566165 HAL Id: hal-01566165 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01566165 Submitted on 20 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License ACAROLOGIA A quarterly journal of acarology, since 1959 Publishing on all aspects of the Acari All information: http://www1.montpellier.inra.fr/CBGP/acarologia/ [email protected] Acarologia is proudly non-profit, with no page charges and free open access Please help -

Universidade De Brasília Instituto De Ciências Biológicas Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Ecologia

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Biológicas Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia “Biodiversidade de Sphingidae (Lepidoptera) nos biomas brasileiros, padrões de atividade temporal diária e áreas prioritárias para conservação de Sphingidae e Saturniidae no Cerrado” Danilo do Carmo Vieira Corrêa Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia como um dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ecologia. Orientadora: Dra. Ivone Rezende Diniz Brasília-DF, julho de 2017 Danilo do Carmo Vieira Corrêa “Biodiversidade de Sphingidae (Lepidoptera) nos biomas brasileiros, padrões de atividade temporal diária e áreas prioritárias para conservação de Sphingidae e Saturniidae no Cerrado” Dissertação aprovada pela Comissão Examinadora em defesa pública para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ecologia junto ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia da Universidade de Brasília. Comissão Examinadora _______________________________________ Profa. Dra. Ivone Rezende Diniz Presidente / Orientadora PPGECL – UnB _______________________________________ Prof. Dr. Felipe Wanderley Amorim Membro Titular Externo Instituto de Biociências – UNESP _______________________________________ Prof. Dr. Paulo César Motta Membro Titular Interno PPGECL – UnB Brasília, 11 de julho de 2017. ii Agradecimentos Externo minha gratidão a todas instituições e pessoas que colaboraram direta e indiretamente para a realização de todas as fases deste trabalho. Particularmente: ao Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade pelo financiamento -

Renée Stout Born 1958, Junction City, Kansas Root Chart # 1, 2006 Graphite on Tracing Vellum Museum Purchase: Letha Churchill Walker Fund, 2008.0329

+ + Israhel van Meckenem the younger (1440 or 1445–1503) born Meckenheim, Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany); died Bocholt, Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany) after Master of the Housebook (circa 1470–1500) The Lovers, late 1400s engraving Gift of the Max Kade Foundation, 1969.0122 In the 15th century, gardens often inspired connotations of courtly love in chivalric medieval romances, poetry, and art. Sometimes referred to as gardens of love or pleasure gardens, these relatively private spaces offered respite from the very public arenas of court. Courtiers would use these gardens to sit, read, play games, roam the walkways, and have discreet meetings. Plants often contributed to the architecture of courtly gardens. Here, the suggestion of a grove sets the tone for the intimate activities of the couple. The smells of flowers and herbs, the colors of blooms and leaves, the sounds of birds, and of the running water of fountains all added to the sensuality of medieval pleasure gardens. + + + + Esaias van Hulsen (circa 1585–1624) born Middelburg, Dutch Republic (present-day Netherlands); died Stuttgart, Duchy of Württemberg (present-day Germany) Console of scrolling foliate forms with flowers and two birds, and a hunter shooting rabbits, circa 1610s engraving Museum purchase: Letha Churchill Walker Memorial Art Fund, 2013.0204 In this engraving van Hulsen carries on the longstanding ornament print tradition of imagining complex, elegant botanical structures. Ornament prints encourage viewers to search through the depicted foliage for partially hidden figures and forms. In this artwork viewers can find insects and birds. Van Hulsen adds a relatively orthodox landscape populated by a rabbit hunter, his dog, and their quarry to this fantastic realm of plants and animals.