The Sphingidae (Bombycoidea) Includes About 1200 Santos Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recolecta De Artrópodos Para Prospección De La Biodiversidad En El Área De Conservación Guanacaste, Costa Rica

Rev. Biol. Trop. 52(1): 119-132, 2004 www.ucr.ac.cr www.ots.ac.cr www.ots.duke.edu Recolecta de artrópodos para prospección de la biodiversidad en el Área de Conservación Guanacaste, Costa Rica Vanessa Nielsen 1,2, Priscilla Hurtado1, Daniel H. Janzen3, Giselle Tamayo1 & Ana Sittenfeld1,4 1 Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio), Santo Domingo de Heredia, Costa Rica. 2 Dirección actual: Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica. 3 Department of Biology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA. 4 Dirección actual: Centro de Investigación en Biología Celular y Molecular, Universidad de Costa Rica. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Recibido 21-I-2003. Corregido 19-I-2004. Aceptado 04-II-2004. Abstract: This study describes the results and collection practices for obtaining arthropod samples to be stud- ied as potential sources of new medicines in a bioprospecting effort. From 1994 to 1998, 1800 arthropod sam- ples of 6-10 g were collected in 21 sites of the Área de Conservación Guancaste (A.C.G) in Northwestern Costa Rica. The samples corresponded to 642 species distributed in 21 orders and 95 families. Most of the collections were obtained in the rainy season and in the tropical rainforest and dry forest of the ACG. Samples were obtained from a diversity of arthropod orders: 49.72% of the samples collected corresponded to Lepidoptera, 15.75% to Coleoptera, 13.33% to Hymenoptera, 11.43% to Orthoptera, 6.75% to Hemiptera, 3.20% to Homoptera and 7.89% to other groups. -

Lepidoptera Sphingidae:) of the Caatinga of Northeast Brazil: a Case Study in the State of Rio Grande Do Norte

212212 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 59(4), 2005, 212–218 THE HIGHLY SEASONAL HAWKMOTH FAUNA (LEPIDOPTERA SPHINGIDAE:) OF THE CAATINGA OF NORTHEAST BRAZIL: A CASE STUDY IN THE STATE OF RIO GRANDE DO NORTE JOSÉ ARAÚJO DUARTE JÚNIOR Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Departamento de Sistemática e Ecologia, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 58059-900, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] AND CLEMENS SCHLINDWEIN Departamento de Botânica, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Av. Prof. Moraes Rego, s/n, Cidade Universitária, 50670-901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil. E-mail:[email protected] ABSTRACT: The caatinga, a thorn-shrub succulent savannah, is located in Northeastern Brazil and characterized by a short and irregular rainy season and a severe dry season. Insects are only abundant during the rainy months, displaying a strong seasonal pat- tern. Here we present data from a yearlong Sphingidae survey undertaken in the reserve Estação Ecológica do Seridó, located in the state of Rio Grande do Norte. Hawkmoths were collected once a month during two subsequent new moon nights, between 18.00h and 05.00h, attracted with a 160-watt mercury vapor light. A total of 593 specimens belonging to 20 species and 14 genera were col- lected. Neogene dynaeus, Callionima grisescens, and Hyles euphorbiarum were the most abundant species, together comprising up to 82.2% of the total number of specimens collected. These frequent species are residents of the caatinga of Rio Grande do Norte. The rare Sphingidae in this study, Pseudosphinx tetrio, Isognathus australis, and Cocytius antaeus, are migratory species for the caatinga. -

Preliminary Studies of the Biodiversity in Garay Cue

ISSN 2313-0504 1(11)2014 PARAGUAY BIODIVERSITY PARAGUAY BIODIVERSITÄT Lasionota dispar (Kerremans, 1903) foto: U. Drechsel Asunción, Agosto 2014 Paraguay Biodiversidad 1(11) 51-60 Asunción, Agosto 2014 Preliminary studies of the Biodiversity in Garay Cue “Reserva Natural Privada Cerrados del Tagatiya” Ulf Drechsel* Abstract: Impressions during four short visits in recent years in the "Reserva Natural Privada Cerrados del Tagatiya " in the Estancia Garay Cué are represented by photographic documentation. Resumen: Impresiones durante cuatro visitas cortas en los últimos años en la " Reserva Natural Privada Cerrados del Tagatiya " en la Estancia Garay Cué están representados por una documentación fotográfica. Zusammenfassung: Eindruecke von vier Kurzbesuchen in den letzten Jahren in der “Reserva Natural Privada Cerrados del Tagatiya” in der Estancia Garay Cué werden durch fotographische Dokumentation dargestellt. Key words: Paraguay, Garay Cue, biodiversity In the northeast of the Department of Concepción in the eastern region of Paraguay is located the Estancia Garay Cué with an area of about 18,800 ha, of which form about 5,200 ha the " Reserva Natural Privada Cerrados del Tagatiya", a nature reserve under private management. The estancia is located between two national parks, the "Parque Nacional Paso Bravo" in the Northeast and the "Parque Nacional Serrania de San Luis" in the West and include semi-deciduous forests, gallery forests and various types of Cerrado. During four short visits from December 2012 to June 2013 could be obtained first impressions of the existing biodiversity and photos of plants and animals were made. Special attention was paid to the most neglected invertebrate fauna, as this is the main part of biodiversity with thousands of species, many of them still unknown to science. -

Final Report for the University of Nottingham / Operation Wallacea Forest Projects, Honduras 2004

FINAL REPORT for the University of Nottingham / Operation Wallacea forest projects, Honduras 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS FINAL REPORT FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF NOTTINGHAM / OPERATION WALLACEA FOREST PROJECTS, HONDURAS 2004 .....................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................................................3 List of the projects undertaken in 2004, with scientists’ names .........................................................................4 Forest structure and composition ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bat diversity and abundance ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Bird diversity, abundance and ecology ............................................................................................................................ 4 Herpetofaunal diversity, abundance and ecology............................................................................................................. 4 Invertebrate diversity, abundance and ecology ................................................................................................................ 4 Primate behaviour........................................................................................................................................................... -

Further Records of Ecuadorian Sphingidae (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) 137-141 - 1 3 7

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Neue Entomologische Nachrichten Jahr/Year: 1998 Band/Volume: 41 Autor(en)/Author(s): Racheli Luigi, Racheli Tommaso Artikel/Article: Further records of Ecuadorian Sphingidae (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) 137-141 - 1 3 7 - Further records of Ecuadorian Sphingidae (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) by Luigi Racheli & T ommaso Racheli Abstract Distributional records of 22 hawkmoths species of Ecuador are reported. In the past, distributional data on the ecuadorian Sphingidae were reported by Dognin (1886-1897), Campos (1931), Rothschild & J ordan (1903) and Schreiber (1978). Haxaire (1991), describing a new species of Xylophanes from Ecuador, has reported a total of 135 species collected in Ecuador. Racheli & R acheli (1994) listed 167 species, including recent collecting data for 80 species, and all the records for the country extracted from the literature, including also doubtful records such as Manduca muscosa (Rothschild & J ordan , 1903) and Xylophanes juanita Rothschild & J ordan , 1903 which are unlikely to occur in Ecuador. The total number of hawkmoths species of Ecuador may account for approximately 155-160 spe cies. Following the recent studies of Racheli & R acheli (1994, 1995), Racheli (1996) and Haxaire (1995, 1996a, 1996b), additional records of Museum specimens and of material collected in Ecuador are given herewith. All the specimens reported below are in the collection of the senior author unless otherwise stated. Abbreviations: Imbabura (IM); Esmeraldas (ES); Pichincha (PI); Ñapo (NA); Pastaza (PA); Morona Santiago (MS). EMEM = Entomologische Museum (Dr, Ulf Eitschberger ), Marktleuthen, Germany; ZSBS = Zoologische Saammlungen des Bayerischen, München, Germany. Sphinginae Manduca lefeburei lefeburei (Guérin-Ménéville , 1844) Remarks: In Ecuador, it is distributed on both sides of the Andes and according to Haxaire (1995) it coexists with Manduca andicola (Rothschild & J ordan , 1916). -

Lepidoptera, Sphingidae, Smerinthinae)

Lucas Waldvogel Cardoso Contribuição de marcadores morfológicos e moleculares na elucidação da Sistemática de Ambulycini (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae, Smerinthinae) Contribution of morphological and molecular markers to the elucidation of the Ambulycini systematics (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae, Smerinthinae) São Paulo 2015 Exemplar corrigido O original encontra-se disponível no Instituto de Biociências da USP Lucas Waldvogel Cardoso Contribuição de marcadores morfológicos e moleculares na elucidação da Sistemática de Ambulycini (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae, Smerinthinae) Contribution of morphological and molecular markers to the elucidation of the Ambulycini systematics (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae, Smerinthinae) Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo, para a obtenção de Título de Mestre em Ciências Biológicas, na Área de Zoologia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Marcelo Duarte da Silva São Paulo 2015 Ficha Catalográfica Waldvogel Cardoso, Lucas Contribuição de marcadores morfológicos e moleculares na elucidação da Sistemática de Ambulycini (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae, Smerinthinae) 187 + iv pp. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Zoologia. 1. Ambulycini 2. Filogenia 3. Filogeografia 4. Conservação I. Universidade de São Paulo. Instituto de Biociências. Departamento de Zoologia. Comissão Julgadora: ________________________ _______________________ Prof(a). Dr(a). Prof(a). Dr(a). ______________________ Prof(a). Dr.(a). Orientador(a) Dedicatória À minha família, a quem devo todas as minhas conquistas. Epígrafe ‘‘The crux of the problem is that if we don’t know what is out there or how widely species are distributed, how can we convince people about the reality and form of the biodiversity crisis?’’ Riddle et al. (2011). Agradecimentos Inicialmente, ao Prof. Dr. Marcelo Duarte, a quem devo muito pela paciência e compreensão. -

Influence De La Pluviométrie Et De La Mise En Place Du Barrage De Petit Saut (Guyane Française) Sur La Répartition Des Lépidoptères Sphingidae

INFLUENCE DE LA PLUVIOMÉTRIE ET DE LA MISE EN PLACE DU BARRAGE DE PETIT SAUT (GUYANE FRANÇAISE) SUR LA RÉPARTITION DES LÉPIDOPTÈRES SPHINGIDAE 1 1 1 1 P. CERDAN , R. VIGOUROUX , V. HOREAU & S. RICHARD SUMMARY The family Sphingidae bas an important potential as bio-indicators given the 118 species so far enumerated in French Guiana. For instance, more than 25,000 individuals from 104 species have been captured during 90 monthly censuses between January 1990 and October 1997 in the region of Petit Saut, a low-altitude primary forest. Among these species, seven are considered as uncommon on the site of Petit Saut. Therefore, ca 50 % of the species with a sufficient number of individuals for the analysis (n = 30) display particular character istics: the probability of occurrence differs significantly between months for 14.5 % of them, and for the majority of the species of this farnily seasonal variations in populations abundances are not linked to rainfall, which is usually the most important ecological factor in this environment, temperature being constant in Guianan forest. These fluctuations are therefore due to other factors. The filling of the dam reservoir affected about a third of the species. Adaptations to variations in environmental conditions are not identical across al! species. Certain species were not affected by environmental modifications while others grew up taking advantage of these changes and colonized new biotopes, and others decreased. RÉSUMÉ La famille des Sphingidés a des capacités bio-indicatrices très performantes compte tenu des 118 espèces connues en Guyane française. Par exemple, plus de 25 000 individus appartenant à 104 espèces ont été capturés lors des 90 piégeages mensuels effectués entre janvier 1990 et octobre 1997 dans une zone de forêt primaire de basse altitude dans la région de Petit Saut. -

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae): Evidence from Five Nuclear Genes

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae): Evidence from Five Nuclear Genes Akito Y. Kawahara1*, Andre A. Mignault1, Jerome C. Regier2, Ian J. Kitching3, Charles Mitter1 1 Department of Entomology, College Park, Maryland, United States of America, 2 Center for Biosystems Research, University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, College Park, Maryland, United States of America, 3 Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom Abstract Background: The 1400 species of hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) comprise one of most conspicuous and well- studied groups of insects, and provide model systems for diverse biological disciplines. However, a robust phylogenetic framework for the family is currently lacking. Morphology is unable to confidently determine relationships among most groups. As a major step toward understanding relationships of this model group, we have undertaken the first large-scale molecular phylogenetic analysis of hawkmoths representing all subfamilies, tribes and subtribes. Methodology/Principal Findings: The data set consisted of 131 sphingid species and 6793 bp of sequence from five protein-coding nuclear genes. Maximum likelihood and parsimony analyses provided strong support for more than two- thirds of all nodes, including strong signal for or against nearly all of the fifteen current subfamily, tribal and sub-tribal groupings. Monophyly was strongly supported for some of these, including Macroglossinae, Sphinginae, Acherontiini, Ambulycini, Philampelini, Choerocampina, and Hemarina. Other groupings proved para- or polyphyletic, and will need significant redefinition; these include Smerinthinae, Smerinthini, Sphingini, Sphingulini, Dilophonotini, Dilophonotina, Macroglossini, and Macroglossina. The basal divergence, strongly supported, is between Macroglossinae and Smerinthinae+Sphinginae. All genes contribute significantly to the signal from the combined data set, and there is little conflict between genes. -

Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) in Savannahs in the Alter Do Chão Protection Area, Santarém, Pará, Brazil

Acta Scientiarum http://periodicos.uem.br/ojs/acta ISSN on-line: 1807-863X Doi: 10.4025/actascibiolsci.v42i2.49064 ECOLOGY Temporal variation and ecological parameters of hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) in savannahs in the Alter do Chão protection area, Santarém, Pará, Brazil Ana Carla Walfredo da Conceição1* and José Augusto Teston1,2 ¹Programa de Pós-Graduação de Recursos Naturais da Amazônia, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, Rua Vera Paz, s/n, 68040-255, Santarém, Pará, Brazil. 2Laboratório de Estudos de Lepidópteros Neotropicais, Instituto de Ciências da Educação, Museu de Zoologia, Santarém, Pará, Brazil. *Author for correspondence. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. This study evaluated the seasonality of Sphingidae spp. in two areas of savannah, in the eastern Brazilian Amazon, sampled for one year (June, 2014 through May, 2015) with the aid of Pennsylvania light traps placed at four sampling points. Data on fauna were obtained through the following parameters: abundance (N), richness (S), composition, Shannon diversity and uniformity indices (H’ and U’), and the Berger-Parker (BP) dominance index. Richness estimates were calculated using Bootstrap, Chao1, ACE, Jackknife 1, and Jackknife2 estimators. The Pearson correlation was also used to analyze the effect of climatic variables such as rainfall, temperature, and relative humidity on richness and abundance. The result for the parameters analyzed during the entire sampling period was N= 374, S= 34, H’= 2.59, U= 0.733 and BP= 0.235. The estimation of richness showed that between 63% and 87% of expected species were collected (Bootstrap estimated 39 species and Chao1 estimated 54). The most representative species were: Isognathus caricae (Linnaeus, 1758) (N= 88), Enyo lugubris lugubris (Linnaeus, 1771) (N= 58), Isognathus menechus (Boisduval, [1875]) (N= 46) and Cocytius duponchel (Poey, 1832) (N= 44), with 54% of the sample containing species considered rare divided into 298 male and 76 female specimens. -

Lista De Anexos

LISTA DE ANEXOS ANEXO N°1 MAPA DEL HUMEDAL ANEXO N°2 REGIMEN DE MAREAS SAN JUAN DEL N. ANEXO N°3 LISTA PRELIMINAR DE FAUNA SILVESTRE ANEXO N°4 LISTA PRELIMINAR DE VEGETACIÓN ANEXO N°5 DOSSIER FOTOGRAFICO 22 LISTADO PRELIMINAR DE ESPECIES DE FAUNA SILVESTRE DEL REFUGIO DE VIDA SILVESTRE RIO SAN JUAN. INSECTOS FAMILIA ESPECIE REPORTADO POR BRENTIDAE Brentus anchorago Giuliano Trezzi CERAMBYCIDAE Acrocinus longimanus Giuliano Trezzi COCCINELLIDAE Epilachna sp. Giuliano Trezzi COENAGRIONIDAE Argia pulla Giuliano Trezzi COENAGRIONIDAE Argia sp. Giuliano Trezzi FORMICIDAE Atta sp. Giuliano Trezzi FORMICIDAE Paraponera clavata Giuliano Trezzi FORMICIDAE Camponotus sp. Giuliano Trezzi GOMPHIDAE Aphylla angustifolia Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Micrathyria aequalis Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Micrathyria didyma Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Erythemis peruviana Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Erythrodiplax connata Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Erythrodiplax ochracea Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Dythemis velox Giuliano Trezzi LIBELLULIDAE Idiataphe cubensis Giuliano Trezzi NYMPHALIDAE Caligo atreus Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Archaeoprepona demophoon Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Eueides lybia Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Dryas iulia Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius charitonius Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius cydno Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius erato Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius melponeme Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Heliconius sara Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Philaetria dido Javier Baltodano NYMPHALIDAE Aeria eurimedia -

Orchid Floral Fragrances and Their Niche in Conservation

Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 THE SCENT OF A GHOST Orchid Floral Fragrances and Their Niche in Conservation James J. Sadler WHAT IS FLORAL FRAGRANCE? It is the blend of chemicals emitted by a flower to attract pollinators. These chemicals sometimes cannot be detected by our nose. 1 Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 WHY STUDY FLORAL FRAGRANCE? Knowing the floral compounds may help improve measures to attract specific pollinators, increasing pollination and fruit-set to augment conservation. Chemical compounds can be introduced to increase pollinator density. FLORAL FRAGRANCE: BACKGROUND INFORMATION 90 plant families worldwide have been studied for floral fragrance, especially the Orchidaceae6 > 97% of orchid species remain unstudied7 Of all plants studied so far, the 5 most prevalent compounds are: limonene (71%), (E)-β-ocimene (71%), myrcene (70%), linalool (70%), and α-pinene (67%)6 2 Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 POSSIBLE POLLINATORS BEES Found to pollinate via mimicry POSSIBLE POLLINATORS WASPS Similar as bees 3 Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 POSSIBLE POLLINATORS FLIES Dracula spp. produce a smell similar to fungus where the eggs are laid POSSIBLE POLLINATORS MOTHS Usually white, large and fragrant at night 4 Florida Orchid Conservation Conference 2011 CASE STUDY The Ghost Orchid State Endangered1 Dendrophylax lindenii THE GHOST ORCHID Range: S Florida to Cuba Epiphyte of large cypress domes and hardwood hammocks Often affixed to pond apple or pop ash Leafless Flowers May-August 5 Florida -

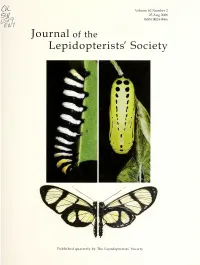

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society

Volume 62 Number 2 25 Aug 2008 ISSN 0024-0966 Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society Published quarterly by The Lepidopterists' Society ) ) THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY Executive Council John H. Acorn, President John Lill, Vice President William E. Conner, Immediate Past President David D. Lavvrie, Secretary Andre V.L. Freitas, Vice President Kelly M. Richers, Treasurer Akito Kayvahara, Vice President Members at large: Kim Garwood Richard A. Anderson Michelle DaCosta Kenn Kaufman John V. Calhoun John H. Masters Plarry Zirlin Amanda Roe Michael G. Pogue Editorial Board John W. Rrovvn {Chair) Michael E. Toliver Member at large ( , Brian Scholtens (Journal Lawrence F. Gall ( Memoirs ) 13 ale Clark {News) John A. Snyder {Website) Honorary Life Members of the Society Charles L. Remington (1966), E. G. Munroe (1973), Ian F. B. Common (1987), Lincoln P Brower (1990), Frederick H. Rindge (1997), Ronald W. Hodges (2004) The object of The Lepidopterists’ Society, which was formed in May 1947 and formally constituted in December 1950, is “to pro- mote the science of lepidopterology in all its branches, ... to issue a periodical and other publications on Lepidoptera, to facilitate the exchange of specimens and ideas by both the professional worker and the amateur in the field; to secure cooperation in all mea- sures” directed towards these aims. Membership in the Society is open to all persons interested in the study of Lepidoptera. All members receive the Journal and the News of The Lepidopterists’ Society. Prospective members should send to the Assistant Treasurer full dues for the current year, to- gether with their lull name, address, and special lepidopterological interests.