Racialisation, Relationality and Riots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brave New World Service a Unique Opportunity for the Bbc to Bring the World to the UK

BRAVE NEW WORLD SERVIce A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY FOR THE BBC TO BRING THE WORLD TO THE UK JOHN MCCaRTHY WITH CHARLOTTE JENNER CONTENTS Introduction 2 Value 4 Integration: A Brave New World Service? 8 Conclusion 16 Recommendations 16 INTERVIEWEES Steven Barnett, Professor of Communications, Ishbel Matheson, Director of Media, Save the Children and University of Westminster former East Africa Correspondent, BBC World Service John Baron MP, Member of Foreign Affairs Select Committee Rod McKenzie, Editor, BBC Radio 1 Newsbeat and Charlie Beckett, Director, POLIS BBC 1Xtra News Tom Burke, Director of Global Youth Work, Y Care International Richard Ottaway MP, Chair, Foreign Affairs Select Committee Alistair Burnett, Editor, BBC World Tonight Rita Payne, Chair, Commonwealth Journalists Mary Dejevsky, Columnist and leader writer, The Independent Association and former Asia Editor, BBC World and former newsroom subeditor, BBC World Service Marcia Poole, Director of Communications, International Jim Egan, Head of Strategy and Distribution, BBC Global News Labour Organisation (ILO) and former Head of the Phil Harding, Journalist and media consultant and former World Service training department Director of English Networks and News, BBC World Service Stewart Purvis, Professor of Journalism and former Lindsey Hilsum, International Editor, Channel 4 News Chief Executive, ITN Isabel Hilton, Editor of China Dialogue, journalist and broadcaster Tony Quinn, Head of Planning, JWT Mary Hockaday, Head of BBC Newsroom Nick Roseveare, Chief Executive, BOND Peter -

Challenging the Whiteness of Britishness: Co-Creating British Social History in the Blogosphere

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Special Issue – September 2015 Challenging the Whiteness of Britishness: Co-Creating British Social History in the Blogosphere Deborah Gabriel, Bournemouth University, UK Abstract Blogs are a valuable medium for preserving cultural memory, reflecting the various dimensions of human life (O’Sullivan, 2005) and allowing ordinary individuals and marginalised groups the opportunity to contribute to the ‘dialogue of history’ (Cohen, 2005:10). The diverse perspectives to be found in the blogosphere can help deepen understanding of historical moments. Such examples include 9/11 (Cohen, 2005), the London bombings in 2005 (Allan, 2006) and Hurricane Katrina (Brock, 2009). Using critical race theory (CRT) as a theoretical framework and cultural democracy as the conceptual framework, this study examines the symbolic power of counter-storytelling through the blogosphere. The findings reveal that in relation to coverage of the UK ‘riots’ in 2011 and the Stephen Lawrence verdict in 2012, African Caribbean bloggers advanced alternative perspectives of the events and appropriated blogs as a medium for self-representation through their own constructions of Black identity. In so doing they performed a vital role as co- creators of British social history. 1 Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Special Issue – September 2015 Introduction Historical archives in Britain often exclude or fail to capture the presence and experiences of people of colour (which dates back to the 17th century with the first arrival of slaves from the west coast of Africa), resulting in a ‘whitenening of Britishness’ Bressey (2006:51). The term is defined as a process through which the exclusion of a person’s skin colour in historical records results in the assumption of a white identity (Bressey, 2006). -

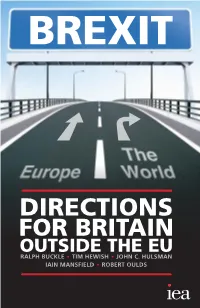

Directions for Britain Outside the Eu Ralph Buckle • Tim Hewish • John C

BREXIT DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE • TIM HEWISH • JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD • ROBERT OULDS BREXIT: Directions for Britain Outside the EU BREXIT: DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE TIM HEWISH JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD ROBERT OULDS First published in Great Britain in 2015 by The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Westminster London SW1P 3LB in association with London Publishing Partnership Ltd www.londonpublishingpartnership.co.uk The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society by analysing and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2015 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-255-36682-3 (interactive PDF) Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Director General at the address above. Typeset in Kepler by T&T Productions Ltd www.tandtproductions.com -

Audience Attitudes to the Licence Fee and Public Service Broadcasting Provision Beyond the BBC

Audience attitudes to the licence fee and public service broadcasting provision beyond the BBC A report by Human Capital Based on data collected by Ipsos MORI and the Knowledge Agency December 2008 Audience attitudes to the licence fee and public service broadcasting beyond the BBC: A report by Human Capital, December 2008 Contents 1 Executive summary ..........................................................................................3 2 Introduction.....................................................................................................13 3 The licence fee research ................................................................................16 4 Future priorities and willingness to pay for PSB on commercially funded PSBs .......................................................................................................................36 2 Audience attitudes to the licence fee and public service broadcasting beyond the BBC: A report by Human Capital, December 2008 1 Executive summary 1.1 Introduction This report sets out the audience research commissioned by the BBC to inform its submission to Ofcom as part of Phase 2 of the Second Review into Public Service Broadcasting (PSB). Human Capital, an independent media consultancy, was commissioned to analyse and draw together all strands of research, including data collected by Ipsos MORI and the Knowledge Agency as part of the BBC’s Phase 2 response to this Review. Building on a large body of existing evidence around PSB, this research focused specifically on two -

The Middle East and Countries of The

THE MIDDLE EAST and countries of the FSU A GUIDE to LISTENING IN ENGLISH GMT +2 TO GMT +4⁄ NOVEMBER 2010 – marcH 2011 including Egypt, Eastern Mediterranean (GMT +2), Sudan, Gulf States, Iraq (GMT +3), Iran (GMT +3∕), UAE (GMT +4) and South Afghanistan (GMT +4∕) Where you see this sign v you will hear a short News Update at 30 minutes past the hour GMT SaturdaY SundaY MondaY TuesdaY WednesdaY ThursdaY FridaY GMT 0:00 News News World Briefing v World Briefing v World Briefing v World Briefing v World Briefing v 0:00 0:06 Global Business v Heart & Soul (P) 0:06 0:32 The Interview One Planet (P) 0:32 0:41 Sports Roundup Sports Roundup Sports Roundup Sports Roundup Sports Roundup 0:41 0:50 Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 0:50 1:00 News World Briefing News News News News News 1:00 1:06 Friday Documentary v The Forum v Monday Documentary v Global Business v Wednesday Documentary v Assignment v 1:06 1:20 Sports Roundup v 1:20 1:32 Science in Action FOOC Health Check Digital Planet Discovery One Planet 1:32 2:00 News News World Briefing News News News News 2:00 2:06 Outlook v Assignment v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v 2:06 2:20 World Business News v 2:20 2:32 The Strand World of Music Letter From..... The Strand The Strand The Strand The Strand 2:32 2:41 Over to You 2:41 3:00 The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v 3:00 3:32 Politics UK Something Understood Digital Planet Americana HARDtalk/Bottom Line Heart & Soul Crossing Continents/FOOC 3:32 -

Analysis of the BBC News Online Coverage of the Iraq War

Greenlee School of Journalism and Journalism Publications Communication 2006 Analysis of the BBC News online coverage of the Iraq War Daniela V. Dimitrova Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/jlmc_pubs Part of the Mass Communication Commons The complete bibliographic information for this item can be found at https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ jlmc_pubs/20. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Greenlee School of Journalism and Communication at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journalism Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analysis of the BBC News online coverage of the Iraq War Abstract The BBC and its coverage of the 2003 Iraq War have received much criticism as well as much praise around the world. Some observers have attacked the news coverage of the BBC, claiming it was clearly biased in support of the war, serving as a propaganda tool for the British government. Others have credited the BBC for its in-depth reporting from the war zone, juxtaposing it to the blatantly patriotic U.S. news coverage. This chapter examines the news coverage the BBC provided on its Web site during the 2003 Iraq War and analyzes the themes and Web-specific eaturf es used to enhance war reporting. Disciplines Mass Communication Comments This book chapter is published as Dimitrova, Daniela V. -

David Starkey Published by Harper Press

Henry Virtuous Prince David Starkey Published by Harper Press Extract All text is copyright of the author This opening extract is exclusive to Lovereading. Please print off and read at your leisure. Henry 9/2/08 2:30 PM Page iv HarperPress An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB www.harpercollins.co.uk Visit our authors’ blog: www.fifthestate.co.uk First published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2008 Copyright © Jutland Ltd 2008 Family tree © HarperCollinsPublishers, designed by HL Studios, Oxfordshire 1 David Starkey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library HB ISBN 978-0-00-724771-4 TPB ISBN 978-0-00-729263-9 Typeset in Bell MT by G&M Designs Limited, Raunds, Northamptonshire Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc FSC is a non-profit international organisation established to promote the responsible management of the world’s forests. Products carrying the FSC label are independently certified to assure consumers that they come from forests that are managed to meet the social, economic and ecological needs of present or future generations. Find out more about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Henry 9/2/08 2:30 PM Page 1 INTRODUCTION Henry and I go back a long way. -

Archived BBC Public Responses to Complaints 2020 BBC News, Royal

Archived BBC public responses to complaints 2020 BBC News, Royal Family coverage, January 2020 Summary of complaint We were contacted by viewers who were unhappy with the level of coverage given to the Duke and Duchess of Sussex's announcement that they will be 'stepping back' as senior royals. Our response In our editorial judgement, the announcement that the Duke and Duchess of Sussex planned to quit their frontline roles was a major news story of great constitutional significance as well as widespread public interest. The Duke and Duchess of Sussex have a very high profile at home and abroad and their decision affects the entire Royal Family, as well as raising questions about the levels of public support they enjoy and their charitable roles too. We appreciate viewers may not agree with how this story was covered, but we also made space for other major stories, including developments in Iran and Australia, both of which we have given extensive airtime. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- BBC World Service, Sinhala, January 2020 Summary of complaint We received a number of complaints about BBC Sinhala correspondent, Azzam Ameen, with concerns over his conduct during the Sri-Lankan presidential election. Our response Editorial impartiality is the foundation of the BBC’s global reputation as a trusted news source and this is something which cannot be compromised. The BBC has taken appropriate action as a result of this serious breach of its Editorial Guidelines. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Question Time, BBC One, 16 January 2020 Summary of complaint We were contacted by viewers who were unhappy with the audience makeup of the programme. -

Annie Lennox Among Speakers at Portmeirion

ADVERTISEMENT Mobile News Sport Weather Travel TV Radio More Search BBC News ONE-MINUTE WORLD NEWS News Front Page Page last updated at 06:58 GMT, Friday, 26 February 2010 E-mail this to a friend Printable version Africa Annie Lennox among speakers at Portmeirion conference Americas Pop star Annie Lennox and Asia-Pacific Conservative peer Lord Patten North West Wales Europe are among a number of leading Find out more about what is Middle East figures speaking at a going on across the region South Asia conference in Gwynedd later. UK The theme of the second annual England Names Not Numbers symposium is Northern Ireland trust, privacy and personalisation. SEE ALSO Scotland It is being staged at the Italianate Prisoner remake 'set to go ahead' Wales village of Portmeirion, which was The symposium is being staged at 30 Apr 08 | North West Wales UK Politics Portmeirion the setting for the 1960s North Wales drive for US tourists Education television series, The Prisoner. 10 Oct 07 | Wales Magazine Village is 'bigger than it seems' Business Among the other speakers are MP David Davis and philosopher Alain de Botton. 18 Sep 06 | North West Wales Health RELATED BBC LINKS Science & Environment Labelled "a very British Davos" By Julia Hobsbawm, Portmeirion Technology after the world economic forum in chief executive, RELATED INTERNET LINKS Entertainment Davos, Switzerland, leading Editorial Intelligence Names Not Numbers Also in the news international figures drawn from I admit it. It is no accident ----------------- that our global forum Names Not The BBC is not responsible for the content of external the spheres of business, politics, Numbers, takes place annually at Video and Audio internet sites arts, finance, media, culture and Portmeirion. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/03/2021 01:51:41PM Via Free Access 16 Berger

CHAPTER 1 Confronting the Other/Perceiving the Self National Historiographies and National Stereotypes in Twentieth-Century Europe Stefan Berger Abstract This contribution deals with the relationship between national historiographies and national stereotypes in twentieth-century Europe. It argues that this relationship was extraordinarily diverse and complex and produced a range of different scenarios. After briefly recalling the role and function of stereotypes and after providing the briefest of introductions to national history writing, it presents five brief case studies. They are, first, the contributions of British and German historians to national stereotyping during the First World War. Secondly, the contribution recalls the stereotyping that fol- lowed from the research of so-called Volksgeschichte in Germany during the interwar period. Thirdly, the need to nationalise territories in East-Central and Eastern Europe that had previously not belonged to the nation state gave rise to the formation of new national stereotypes after the end of the Second World War. Fourthly, the hyperna- tionalism of the first half of the twentieth century threw a range of national historical master narratives into a severe crisis after 1945 and created the need to reframe those narratives in the post-Second World War world. The final case study deals with a sim- ilar need to recast national historical master narratives after the end of the Cold War from the 1990s onwards. 1 Introduction Standing on Gianicolo Hill overlooking Rome one is confronted with the mon- ument to Giuseppe Garibaldi, unveiled in 1895. Garibaldi was, of course, one of the central heroes of the Risorgimento – an archetypal romantic figure fighting the cause of national unity and liberty not just in Italy but also in Latin America. -

Complaints to the BBC Stage 1 Complaints

Complaints to the BBC This fortnightly report for the BBC complaints service1 shows for the periods covered: the number of complaints about programmes and those which received more than 1002 at Stage 1 (Audience Services); findings of subsequent investigations made at Stage 2 (by the Executive Complaints Unit)3; the percentage of all complaints dealt with within the target periods for each stage. NB: Figures include, but are not limited to, editorial complaints, and are not comparable with complaint figures published by Ofcom about other broadcasters (which are calculated on a different basis). The number of complaints received is not an indication of how serious an issue is. Stage 1 complaints Between 22 June – 5 July 2020, BBC Audience Services (Stage 1) received a total of 5,447 complaints about programmes. 10,176 complaints in total were received at Stage 1. BBC programmes which received more than 100 complaints during this period: Programme Service Date of Main Issue(s) Number of Transmission Complaints Lunchtime Live BBC 23/06/20 Bias against Scotland 146 Radio by not showing the Scotland First Minister’s daily Coronavirus update in full/switching to Westminster. Countryfile BBC One 28/06/20 Report on members of 572 the BAME community living in the countryside felt to be inaccurate. Drivetime BBC 29/06/20 Bias against the 104 Radio police/offensive line Scotland of questioning. BBC News (6pm) Radio 4 02/07/20 Inaccurate description 628 (After of the ‘Reasoned UK’ invitations to website / bias against complain were Darren Grimes and/or posted online) David Starkey 1 Full details of the service are in the BBC Complaints Framework and Procedures document. -

BBC World Class 2012 World’S Biggest School Assembly, 8 May BBC World Class and World Have Your Say PHOTO/INTERVIEW CONSENT FORM

BBC World Class 2012 www.bbc.co.uk/worldclass World’s Biggest School Assembly, 8 May BBC World Class and World Have Your Say PHOTO/INTERVIEW CONSENT FORM Please sign this form and photograph/scan and email to [email protected]. BBC World Class is the BBC’s international school twinning project, and focuses on schools in the UK with international partnerships, shares good practice and encourages more schools to get involved. The hub of the project is a website: www.bbc.co.uk/worldclass. We are encouraging schools around the world to collaborate and we share their story with other BBC teams on BBC websites, radio or television. World Have Your Say is the BBC World Service global conversation programme and is broadcast on BBC World Service English network. Both teams also work with BBC outlets such as other BBC websites, radio or television. This is a general form to be signed by the parent or legal guardian or head teacher of pupils to provide consent for material gathered during school time. I confirm that BBC World Class and World Have Your Say can use interviews, quotations, photos, videos and other contributions from: _____________________________________________(name of pupil/class/school) I confirm that where images have been provided or video is taken, I consent for them to be used on the World Class website at www.bbc.co.uk/worldclass. I understand the contributions and photographs may be made available to other BBC colleagues for use on other BBC websites or be used to promote BBC World Class in other ways.