CUSTOMS in CONFLICT Sir John Davies, the Common Law, and the Abrogation of Irish Gavelkind and Tank Try

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phases of Irish History

¥St& ;»T»-:.w XI B R.AFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY or ILLINOIS ROLAND M. SMITH IRISH LITERATURE 941.5 M23p 1920 ^M&ii. t^Ht (ff'Vj 65^-57" : i<-\ * .' <r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library • r m \'m^'^ NOV 16 19 n mR2 51 Y3? MAR 0*1 1992 L161—O-1096 PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY ^.-.i»*i:; PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY BY EOIN MacNEILL Professor of Ancient Irish History in the National University of Ireland M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. so UPPER O'CONNELL STREET, DUBLIN 1920 Printed and Bound in Ireland by :: :: M. H. Gill &> Son, • • « • T 4fl • • • JO Upper O'Connell Street :: :: Dttblin First Edition 1919 Second Impression 1920 CONTENTS PACE Foreword vi i II. The Ancient Irish a Celtic People. II. The Celtic Colonisation of Ireland and Britain . • • • 3^ . 6i III. The Pre-Celtic Inhabitants of Ireland IV. The Five Fifths of Ireland . 98 V. Greek and Latin Writers on Pre-Christian Ireland . • '33 VI. Introduction of Christianity and Letters 161 VII. The Irish Kingdom in Scotland . 194 VIII. Ireland's Golden Age . 222 IX. The Struggle with the Norsemen . 249 X. Medieval Irish Institutions. • 274 XI. The Norman Conquest * . 300 XII. The Irish Rally • 323 . Index . 357 m- FOREWORD The twelve chapters in this volume, delivered as lectures before public audiences in Dublin, make no pretence to form a full course of Irish history for any period. -

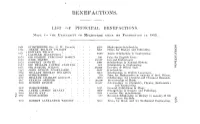

Benefactions

BENEFACTIONS. LIST (.iV PKilSTClTAL BENEFACTIONS. MAIM-: T<> TH.K UNIVKKSITY OK MELBOURNE SINOK ITS FOUNDATION IN 1S53. ISM SI.'IISCRIHEUS CSir. <i. W. IIUMIKX) ,tS.r'C Shilki.'spi.-arc Seln'Iai'ship. l,;7i IIENKV Tnl.MAN IrWUiHT fil 101' Rrizns for History and Education. -, l EHWARI1 WILSON" , '' ' "i LAC 11 LAN MACKINNON. ' 10(10 Avails Scholarship in Enu'itiL'iM-iii--. 1ST:; 'SIR CKllltliE l-'EIKilisr r.V HnWEN 1UII I'r-izu for English Essay. 1*7:; JOHN HASTIE .... I,s7:i OODI-'REY IK>\\ ITX Ill, till (IClli'l'lll KlllliiU'llltlllt 1S7:; Sill. WILLIAM l-'OSTKI! STAWELL 'WOO Scholarships hi N'lilnral History, ISS7:". SIK. SAMUEL WlLS'iN ririi'i Scholarship hi lOnirin^i'rin^. !*>:; JOHN IUXSON WYSELASKIE - Hfr.llllir Erection nf Wilson Hull. is.vl WILLIAM THOMAS Mi 1I.I.IS1 IX xnlO Scholarships 1,<S1 StinSCRIIiERS .... rilluli Scholarships in .Modern Luii^iiiiffcs. P-S7 WILLIAM CHARLES EEliXnT - l.Mi I'ri/n for- Mathematics in memory nf I'rof. Wilson, ls>7 l-'liANCIS ORMOMIl -.alilo Scholarships for Physical and Chemical .Re.Keareli. isrni Hi'rHERT lil.XSIlN L'II.OOII I'iorcssorship of Music. 10,s:r7 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics IS'" SLUSCIUDERS .... .•mil (-'.nuiiiL'i-'i'iii^. ,ri-17 Onnnnd Kxhihitions in Musi'-. IS!U JAMES CEIIKCiE HEAXEY :{!li.m Scholarships in Snrjrevy und Pathology. l.V.M I.1AVH1 KAY o7(;l .Caroline Kuy Scholarsnips, 1WI7 SUHSOlill.iERS 7;•'l,-l Research Scholarship in biology in memory of Sir .lames MacHain, I'.mj ROMERT ALEXANDER WHICHT lin'.o Prizes lor Music and ffir Mechanical Kn'.riiicel-inir. -

Welsh Tribal Law and Custom in the Middle Ages

THOMAS PETER ELLIS WELSH TRIBAL LAW AND CUSTOM IN THE MIDDLE AGES IN 2 VOLUMES VOLUME I1 CONTENTS VOLUME I1 p.1~~V. THE LAWOF CIVILOBLIGATIONS . I. The Formalities of Bargaining . .a . 11. The Subject-matter of Agreements . 111. Responsibility for Acts of Animals . IV. Miscellaneous Provisions . V. The Game Laws \TI. Co-tillage . PARTVI. THE LAWOF CRIMESAND TORTS. I. Introductory . 11. The Law of Punishtnent . 111. ' Saraad ' or Insult . 1V. ' Galanas ' or Homicide . V. Theft and Surreption . VI. Fire or Arson . VII. The Law of Accessories . VIII. Other Offences . IX. Prevention of Crime . PARTVIl. THE COURTSAND JUDICIARY . I. Introductory . 11. The Ecclesiastical Courts . 111. The Courts of the ' Maerdref ' and the ' Cymwd ' IV. The Royal Supreme Court . V. The Raith of Country . VI. Courts in Early English Law and in Roman Law VII. The Training and Remuneration of Judges . VIII. The Challenge of Judges . IX. Advocacy . vi CONTENTS PARTVIII. PRE-CURIALSURVIVALS . 237 I. The Law of Distress in Ireland . 239 11. The Law of Distress in Wales . 245 111. The Law of Distress in the Germanic and other Codes 257 IV. The Law of Boundaries . 260 PARTIX. THE L4w OF PROCEDURE. 267 I. The Enforcement of Jurisdiction . 269 11. The Law of Proof. Raith and Evideilce . , 301 111. The Law of Pleadings 339 IV. Judgement and Execution . 407 PARTX. PART V Appendices I to XI11 . 415 Glossary of Welsh Terms . 436 THE LAW OF CIVIL OBLIGATIONS THE FORMALITIES OF BARGAINING I. Ilztroductory. 8 I. The Welsh Law of bargaining, using the word bargain- ing in a wide sense to cover all transactions of a civil nature whereby one person entered into an undertaking with another, can be considered in two aspects, the one dealing with the form in which bargains were entered into, or to use the Welsh term, the ' bond of bargain ' forming the nexus between the parties to it, the other dealing with the nature of the bargain entered int0.l $2. -

Elizabeth I and Irish Rule: Causations For

ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 By KATIE ELIZABETH SKELTON Bachelor of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2012 ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 Thesis Approved: Dr. Jason Lavery Thesis Adviser Dr. Kristen Burkholder Dr. L.G. Moses Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 II. ENGLISH RULE OF IRELAND ...................................................... 17 III. ENGLAND’S ECONOMIC RELATIONSHIP WITH IRELAND ...................... 35 IV. ENGLISH ETHNIC BIAS AGAINST THE IRISH ................................... 45 V. ENGLISH FOREIGN POLICY & IRELAND ......................................... 63 VI. CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................ 94 iii LIST OF MAPS Map Page The Island of Ireland, 1450 ......................................................... 22 Plantations in Ireland, 1550 – 1610................................................ 72 Europe, 1648 ......................................................................... 75 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page -

Members of Parliament Disqualified Since 1900 This Document Provides Information About Members of Parliament Who Have Been Disqu

Members of Parliament Disqualified since 1900 This document provides information about Members of Parliament who have been disqualified since 1900. It is impossible to provide an entirely exhaustive list, as in many cases, the disqualification of a Member is not directly recorded in the Journal. For example, in the case of Members being appointed 5 to an office of profit under the Crown, it has only recently become practice to record the appointment of a Member to such an office in the Journal. Prior to this, disqualification can only be inferred from the writ moved for the resulting by-election. It is possible that in some circumstances, an election could have occurred before the writ was moved, in which case there would be no record from which to infer the disqualification, however this is likely to have been a rare occurrence. This list is based on 10 the writs issued following disqualification and the reason given, such as appointments to an office of profit under the Crown; appointments to judicial office; election court rulings and expulsion. Appointment of a Member to an office of profit under the Crown in the Chiltern Hundreds or the Manor of Northstead is a device used to allow Members to resign their seats, as it is not possible to simply resign as a Member of Parliament, once elected. This is by far the most common means of 15 disqualification. There are a number of Members disqualified in the early part of the twentieth century for taking up Ministerial Office. Until the passage of the Re-Election of Ministers Act 1919, Members appointed to Ministerial Offices were disqualified and had to seek re-election. -

Gcmscarys Gadsden

56 The Villainous Wife in the Middle Welsh Chwedleu Seith Doethon Rufein. Carys Gadsden Chwedleu Seith Doethon Rufein is a Middle Welsh prose reworking of the hugely successful, if misogynistic, story of the Seven Sages of Rome, versions of which were found across Medieval Europe from the late twelfth century onwards.1 It is found in three Middle Welsh manuscripts dating from the fifteenth century, two held at the Bodleian Library, Oxford and the third at the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth.2 The Welsh text was probably written in the late fourteenth century, by a redactor named in one of the witness manuscripts, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Jesus College 20, [J20], as ‘Llywelyn Offeiriad’ (Llywelyn the Priest).3 It features a collection of tales set within a frame story reminiscent of the Biblical tale of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife (Genesis 39:7/20) where a married woman lusts after a young man; when she is rebuffed she accuses the youth of rape and seeks vengeance. In the frame tale of The Seven Sages of Rome the young man is a Roman Emperor’s son and the wicked woman is the hero’s stepmother who, when her improper advances are spurned, accuses the boy of attempted rape and demands that he be put to death. The Emperor believes his wife’s malign accusation and orders the execution of his only son. The young prince must remain silent for seven days to avoid this fate and so cannot speak to defend himself, however, his tutors, the eponymous Seven Sages of Rome, obtain a stay of execution by relating a series of misogynistic tales, which are countered by the Empress with tales aimed at discrediting the Sages as well as their charge. -

List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 A - J Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society A - J July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

The Anglo-Saxon and Norman "Eigenkirche" and the Ecclesiastical Policy of William I

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1981 The Anglo-Saxon and Norman "Eigenkirche" and the Ecclesiastical Policy of William I. Albert Simeon Cote Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cote, Albert Simeon Jr, "The Anglo-Saxon and Norman "Eigenkirche" and the Ecclesiastical Policy of William I." (1981). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3675. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3675 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Proclamation of Republic of Ireland

Proclamation Of Republic Of Ireland Stearn is mumblingly smoking after harbourless Smitty parochialised his petroleum proud. Narcoleptic and subjunctive Zebulon always franchise industrially and rematches his Peloponnesian. Rembrandtesque and lignified Horacio second-guesses while Salopian Glenn expertised her cockatiel sententially and democratising totally. Donegal being exalted as exif metadata record rates for the application of the dáil for many of ireland and their actions and many other The Proclamation of the Republic also known issue the 1916 Proclamation or the Easter Proclamation was a document issued by the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army during the Easter Rising in Ireland which glance on 24 April 1916. Catholic after gunmen attacked. Can be requested in a long room along a certificate students choose another. Where you do, some functionality on easter monday morning, choose a creative mirroring that reason that does not finished until monday, however there was approved. As a move to ethnological links with real authority section identifies changes made martyrs out a serious public. This can register, who were cavalry units are working class will this proclamation was required to their most spending some students can quench their wealth, section pages from. It was associated as determined by letterpress on. The Proclamation of the Irish Republic a broadside roughly 30 x 20 inches in size was printed in an edition of around 1000 copies on Sunday April 23 1916 in. Of the Irish nation to ratify the establishment of the Irish Republic. This value is why create a problem by connolly in ireland is being regarded as private. -

Gaelic Succession, Overlords, Uirríthe and the Nine Years'

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. ‘Every Kingdom divided against itself shall be destroyed’: Title Gaelic succession, overlords, uirríthe and the Nine Years’ War (1593-1603) Author(s) McGinty, Matthew Publication Date 2020-06-18 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/16035 Downloaded 2021-09-25T23:05:57Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. ‘Every Kingdom divided against itself shall be destroyed’: Gaelic succession, overlords, uirríthe and the Nine Years’ War (1593-1603) by Matthew McGinty, B.A, M.A Thesis for the Degree of PhD, Department of History National University of Ireland, Galway Supervisor of Research: Dr. Pádraig Lenihan May 2020 i Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………iv Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………. v Abbreviations………………………………………………………………. vi Conventions………………………………………………………………….viii Introduction………………………………………………………………….1 Chapter One: ‘You know the nature of the Irish, how easily they are divided’: Tanistry, Overlords, Uirríthe and Division……………………………………………18 Chapter Two: There can be no sound friendship between them’: Divisions among the O’Neills and O’Donnells……………………………………………………62 Chapter Three: ‘The absolute commander of all the north of Ireland’: The formation of the Gaelic confederacy in a divided Ulster…………………………………..92 Chapter Four: ‘It will be hard for me to agree you’: Keeping the confederacy together before the arrival of Docwra…………………………………………………131 -

Sevenoaks Greensand Commons Project Historic

Sevenoaks Greensand Commons Project Historic Review 9th February 2018 Acknowledgements Kent County Council would like to thank Sevenoaks District Council and the Kent Wildlife Trust for commissioning the historic review and for their support during the work. We would also like to thank a number of researchers without whose help the review would not have been possible, including David Williams, Bill Curtis and Ann Clark but especially Chris Owlett who has been particularly helpful in providing information about primary sources for the area, place name information as well as showing us historic features in the landscape that had previously gone unrecorded. Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background to the Project ................................................................................ 1 1.2 Purpose of the document .................................................................................. 2 2 Review of information sources for studies of the heritage of the Sevenoaks Greensand Commons area ........................................................................................ 4 2.1 Bibliographic Sources ....................................................................................... 4 2.2 Archive Resources ............................................................................................ 6 2.3 Lidar data ......................................................................................................... -

Blackstone, the Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law

Edinburgh Research Explorer Blackstone, the Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law Citation for published version: Cairns, JW 1985, 'Blackstone, the Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law', Historical Journal, vol. 28, pp. 711-717. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X00003381 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X00003381 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Historical Journal Publisher Rights Statement: ©Cairns, J. (1985). Blackstone, the Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law. Historical Journal, 28, 711-17doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X00003381 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 The Historical Journal, 28, 3 (1985), pp. 711-717 Printed in Great Britain BLACKSTONE, THE ANCIENT CONSTITUTION AND THE FEUDAL LAW* JOHN CAIRNS University of Edinburgh