Migration Dividend Fund

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, 1996-2001

ICPSR 2683 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, 1996-2001 Virginia Sapiro W. Philips Shively Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 4th ICPSR Version February 2004 Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 www.icpsr.umich.edu Terms of Use Bibliographic Citation: Publications based on ICPSR data collections should acknowledge those sources by means of bibliographic citations. To ensure that such source attributions are captured for social science bibliographic utilities, citations must appear in footnotes or in the reference section of publications. The bibliographic citation for this data collection is: Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Secretariat. COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS, 1996-2001 [Computer file]. 4th ICPSR version. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Center for Political Studies [producer], 2002. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2004. Request for Information on To provide funding agencies with essential information about use of Use of ICPSR Resources: archival resources and to facilitate the exchange of information about ICPSR participants' research activities, users of ICPSR data are requested to send to ICPSR bibliographic citations for each completed manuscript or thesis abstract. Visit the ICPSR Web site for more information on submitting citations. Data Disclaimer: The original collector of the data, ICPSR, and the relevant funding agency bear no responsibility for uses of this collection or for interpretations or inferences based upon such uses. Responsible Use In preparing data for public release, ICPSR performs a number of Statement: procedures to ensure that the identity of research subjects cannot be disclosed. Any intentional identification or disclosure of a person or establishment violates the assurances of confidentiality given to the providers of the information. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 512 29 June 2010 No. 23 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 29 June 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 697 29 JUNE 2010 698 almost identical to the chances in the rest of Europe. House of Commons Does the Secretary of State therefore believe that a one-year survival indicator is a good idea both for Tuesday 29 June 2010 encouraging early diagnosis and for matching the survival rates of the best in Europe? The House met at half-past Two o’clock Mr Lansley: My hon. Friend makes an extremely good point. When we set out proposals for an outcomes PRAYERS framework, I hope that he and others will respond, because that is one of the ways in which we can best identify how late detection of cancer is leading to very [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] poor levels of survival to one year. I hope that we can think about that as one of the quality indicators that we shall establish. Oral Answers to Questions Diana R. Johnson (Kingston upon Hull North) (Lab): I welcome the Secretary of State to his new position and wish him well in his role. I understand that he is keeping HEALTH the two-week target for seeing a cancer specialist, but abandoning the work that the Labour Government did on the one-week target for access to diagnostic testing. -

Area Profile

A PROFILE OF NEEDS AND SERVICES ABOUT CHILDREN, YOUNG PEOPLE & THEIR FAMILIES IN THE DUKINFIELD, STALYBRIDGE & MOSSLEY AREAS OF TAMESIDE SEPTEMBER 2007 CONTENTS Page No Dukinfield,Stalybridge & Mossley: Profile of need and services Introduction 2 Contents 3 Part 1: Basic need data 6 Population 6 Index of Multiple Deprivation 7 Ward Profiles 9 Dukinfield profile 9 1: Population data 9 2:Household Composition 9 3:Housing 10 4:Health 10 5:Unemployment 11 6:Education 11 7:Occupation 12 Dukinfield/Stalybridge profile 13 1: Population data 13 2:Household Composition 13 3:Housing 14 4:Health 14 5:Unemployment 14 6:Education 15 7:Occupation 16 Stalybridge North Profile 16 1:Population data 16 2:Household Composition 17 3:Housing 17 4:Health 18 5:Unemployment 18 6:Education 19 7:Occupation 19 Stalybridge South profile 20 1:Population data 20 2:Household Composition 21 3:Housing 21 4:Health 22 5:Unemployment 22 6.Education 23 7:Occupation 24 Mossley profile 24 1:Population data 24 2:Household Composition 25 3:Housing 25 4:Health 26 5:Unmployment 26 6:Education 27 7:Occupation 27 Selected Comparison Tables 28 Teenage Pregnancy Trend 29 Regeneration Profile 30 Part 2: Service Profile 33 Introduction 33 Section 1: Universal Offices 33 School and childcare data 33 1:Nursery Education and childcare 33 2:Primary Schools 34 3:Secondary Schools 34 4:Children’s Centres 35 5:Extended School Services 36 6: Childcare provision:summary 36 A. Childminders 37 B. Day Nurseries 37 C. Playgroups/Preschools 37 D. Out of School Clubs 38 Section 2: Additional services -

Tameside Locality Assessments GMSF 2020

November 2020 Transport Locality Assessments Introductory Note and Assessments – Tameside allocations GMSF 2020 Table of contents 1. Background 2 1.1 Greater Manchester Spatial Framework (GMSF) 2 1.2 Policy Context – The National Planning Policy Framework 3 1.3 Policy Context – Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2040 5 1.4 Structure of this Note 9 2. Site Selection 10 2.1 The Process 10 2.2 Greater Manchester Accessibility Levels 13 3. Approach to Strategic Modelling 15 4. Approach to Technical Analysis 17 4.1 Background 17 4.2 Approach to identifying Public Transport schemes 18 4.3 Mitigations and Scheme Development 19 5. Conclusion 23 6. GMSF Allocations List 24 Appendix A - GMA38 Ashton Moss West Locality Assessment A1 Appendix B - GMA39 Godley Green Garden Village Locality Assessment B1 Appendix C - GMA40 Land South of Hyde Locality Assessment C1 1 1. Background 1.1 Greater Manchester Spatial Framework (GMSF) 1.1.1 The GMSF is a joint plan of all ten local authorities in Greater Manchester, providing a spatial interpretation of the Greater Manchester Strategy which will set out how Greater Manchester should develop over the next two decades up to the year 2037. It will: ⚫ identify the amount of new development that will come forward across the 10 Local Authorities, in terms of housing, offices, and industry and warehousing, and the main areas in which this will be focused; ⚫ ensure we have an appropriate supply of land to meet this need; ⚫ protect the important environmental assets across the conurbation; ⚫ allocate sites for employment and housing outside of the urban area; ⚫ support the delivery of key infrastructure, such as transport and utilities; ⚫ define a new Green Belt boundary for Greater Manchester. -

“Benefit Tourism” and Migration Policy in the UK

“Benefit Tourism” and Migration Policy in the U.K.: The Construction of Policy Narratives Meghan Luhman Ph.D. Candidate, Dept. of Political Science Johns Hopkins University [email protected] February 2015 Draft Prepared for EUSA Conference March 57, 2015, Boston, MA. Please do not cite or circulate without author’s permission. 1 I. Introduction In 2004, ten new member states, eight from Central and Eastern Europe (the socalled “A8” countries), joined the European Union. European Union citizens have the right to freely move throughout and reside in (subject to conditions) all member states. At the time, though thirteen out of fifteen existing E.U. member states put temporary restrictions on migrants from these new member states, the U.K. decided to give these migrants immediate full access to the labor market. While in France, for example, fears about the “Polish plumber” taking French jobs became a hot topic of debate and caused the French to implement temporary controls, in the U.K. Tony Blair highlighted “the opportunities of accession” to fill in gaps in the U.K. economy (The Guardian, 27 April 2004). Blair’s Conservative opponents had also largely supported enlargement in the 1990s, noting the expansion of the E.U. would increase trade and “encourage stability and prosperity” (HC Deb 21 May 2003 vol 405 cc1021). The U.K. was hailed by members of the European Parliament as welcoming, and in spite of some fears of strain on social services and benefits, studies showed that the migrants had been a net benefit for the U.K. -

Denton & Reddish Labour Party, C/O 139 St Anne’S Road, Denton M34 3DY Denton South Delivered FREE by Volunteers √" " Local Oice SPRING 2014 DENTON

Printed by Greatledge, Malaga House, Pink Bank Lane, Manchester M11 2EU Promoted by Denton & Reddish Labour Party, c/o 139 St Anne’s Road, Denton M34 3DY Denton South Delivered FREE by volunteers √" " local oice SPRING 2014 DENTON , chosen for seat again Cllr. Claire Francis Local Labour Councillor Claire Francis, , at the opening has been picked once again to contest Cllr. Claire Francis ‘Oasis’ the Denton South seat in the Tameside of the Haughton Green Council Elections on Thursday 22nd May. Claire has worked hard over the last four years alongside Councillors Mike Fowler, NEW LIFE FOR HG LIBRARY Margaret Downs and local residents, to get a fairer deal for our town. Claire Francis attended the official opening of the ‘Oasis’, the former Haughton Green Library building, which Irwell Valley took on after Tory Government funding cuts forced its closure. Already they have a wide variety of activities happening every week. Claire said: “Denton South is lucky to have Irwell Valley working hard to improve the area and it’s fantastic to know that the local community are willing to work with us all to help preserve vital facilities.” Since 2010, the equivalent of * across Denton and Reddish almost 50p in every £1 has 1,295 families , been cut from Tameside’s grant (which including many by the with Tory disabled Bedroom are Tax are being penalised disability. by this Tory-led Government. including many with a * including the effect of inflation on spending power Labour will scrap this unfair charge . " Andrew Gwynne says Denton’s MP, .penalised Labour’s Claire Francis – Working hard for YOU all year round. -

Area Profile

A profile of needs and s Services about children, young people and their families In the Hyde, Hattersley & Longdendale area of Tameside September 2007 Hyde, Hattersley & Longdendale: Profile of need and services Introduction This is a selective statistical profile of needs and services in the Hyde, Hattersley & Longdendale area, this is one of four areas chosen as a basis from which future integrated services for children, young people and their families will be delivered. The other areas are Ashton-under-Lyne: Denton, Droylsden & Audenshaw and Stalybridge, Mossley & Dukinfield. Companion profiles of these other areas are also available. This profile has a focus on data that has relevance to children and families rather than other community members (e.g. older people). The data selected is not exhaustive, rather key indicators of need are selected to help produce an overall picture of need in the area and offer some comparisons between localities (mainly wards) within the area. Some commentary is provided as appropriate. It is expected that the profile will aid the planning and delivery of services. The profile has two parts: Part 1 focuses on the presentation of basic need data, whilst Part 2 focuses on services. The top three categories of the new occupational classification are ‘Managers & Senior Officials; Professionals’ and Associate Professional & Technical’ (hatched at the top of the graph on right) Tameside as a whole comes 350 th out of 376 in the country for Professional; and bottom in Greater Manchester for all three categories -

Tameside Housing Need Assessment (HNA) (2017) Provides the Latest Available Evidence to Help to Shape the Future Planning and Housing Policies of the Area

Tameside Housing Need Assessment (HNA) 2017 Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council Final Report December 2017 Main Contact: Michael Bullock Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 612 9133 Website: www.arc4.co.uk © 2017 arc4 Limited (Company No. 06205180) Tameside HNA 2017 Page | 2 Table of contents Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 8 The Housing Market Area (HMA) ........................................................................................ 8 The current housing market ................................................................................................ 9 Understanding the future housing market ....................................................................... 11 The need for all types of housing ...................................................................................... 11 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................... 14 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 15 Background and objectives ............................................................................................... 15 National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), Planning Practice Guidance (PPG) and other requirements -

Elections 2008:Layout 1.Qxd

ELECTIONS REPORT Thursday 1 May 2008 PREPARED BY CST 020 8457 9999 www.thecst.org.uk Copyright © 2008 Community Security Trust Registered charity number 1042391 Executive Summary • Elections were held on 1st May 2008 for the • The other far right parties that stood in the Mayor of London and the London Assembly, elections are small and were mostly ineffective, 152 local authorities in England and all local although the National Front polled almost councils in Wales 35,000 votes across five London Assembly constituencies • The British National Party (BNP) won a seat on the London Assembly for the first time, polling • Respect – The Unity Coalition divided into two over 130,000 votes. The seat will be taken by new parties shortly before the elections: Richard Barnbrook, a BNP councillor in Barking Respect (George Galloway) and Left List & Dagenham. Barnbrook also stood for mayor, winning almost 200,000 first and second • Respect (George Galloway) stood in part of the preference votes London elections, polling well in East London but poorly elsewhere in the capital. They stood • The BNP stood 611 candidates in council nine candidates in council elections outside elections around England and Wales, winning London, winning one seat in Birmingham 13 seats but losing three that they were defending. This net gain of ten seats leaves • Left List, which is essentially the Socialist them holding 55 council seats, not including Workers Party (SWP) component of the old parish, town or community councils. These Respect party, stood in all parts of the -

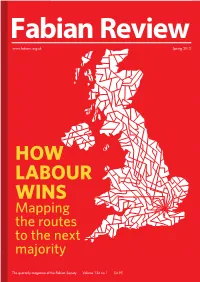

How Labour Wins Mapping the Routes to the Next Majority

Fabian Review www.fabians.org.uk Spring 2012 HOW LABOUR WINS Mapping the routes to the next majority The quarterly magazine of the Fabian Society Volume 124 no 1 £4.95 THE FABIAN SUMMER CONFERENCE Featuring a Q&A with Ed Miliband LABOUR'S next majority 30th June, 10am doors open for an 11am start finishing at around 5pm Millbank Media Centre, Ground Floor, Millbank Tower, 21–24 Millbank, London, SW1P 4QP Tickets for members and concessions are just £10 (£15 for non-members with six months free membership) Come and join the Fabians for our Summer Conference featuring a Question and Answer session with Ed Miliband. Debate Labour’s electoral strategy and put forward your take on some of the ideas we’ve explored in this issue of the Fabian Review. To book your tickets head to www.fabians.org.uk or call 020 7227 4900 EDITORIAL Image: Adrian Teal Age-old lessons Andrew Harrop asks if ongoing public support for pensioner benefits offers the left a way out of its welfare impasse If the polls are to be believed, benefits for pensioners (of which the the poorest get more – which the coali- cutting welfare is very popular. YouGov much-castigated winter fuel payment tion is busy unpicking though its tax reports that fewer than a third of and free bus pass make up just a tiny credit cuts. Labour voters and just 3 per cent of fraction). On top there is a generous A shared system, where every family Conservatives oppose it. This places the means-tested system which has done is a recipient, could open the way for left in a terrible bind, not least because much to reduce pensioner poverty. -

Stalybridge North Ward, Which Comes Into Effect on 10Th June 2004

Census data used in this report are produced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office and are © Crown Copyright Contents Residents Households Health P1 Age Structure of Population P4 Household Size P6 Limiting Long Term Illness Pensioner Households General Health P2 Ethnic Profile of Population Households with Children Carers Country of Birth Lone Parent Households P3 Religion Children in Households Work and Skills Marital Status with no Adult in Living Arrangements Employment P7 Economic Activity Unemployment P5 Tenure Vacant / Second Homes P8 Qualifications Property Size & Type Students Amenities Occupational Group Car Ownership N.B. This profile describes the new Stalybridge North ward, which comes into effect on 10th June 2004. The figures it contains must be regarded as provisional. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has yet to issue official and more accurate Census figures for the new wards. Interpreting Census Statistics Please note that small figures in Census tables are liable to be amended by the ONS to preserve confidentiality. This means that totals and percentages which logically ought to be the same may in fact be different, depending what table they come from. Useful Websites Basic Census results can be found at www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk, but these refer to pre-June 2004 wards. See also www.statistics.gov.uk and www.tameside.gov.uk For further information please contact Anne Cunningham in the Policy Unit on 0161 342 2170, or email [email protected] All data taken from 2001 Census. Technical differences between the 1991 and 2001 Censuses make comparison difficult, and ward definitions have changed since 1991. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Scrutiny Co-Ordinating Board, 13/10

Date: 5 October 2016 Please note the earlier start time Town Hall, Penrith, Cumbria CA11 7QF Tel: 01768 817817 Email: [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam Special Scrutiny Co-ordinating Board Agenda - 13 October 2016 Notice is hereby given that a special meeting of the Scrutiny Co-ordinating Board will be held at 6.00 pm on Thursday, 13 October 2016 at the Council Chamber, Town Hall, Penrith. 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Declarations of Interest To receive declarations of the existence and nature of any private interests, both disclosable pecuniary and any other registrable interests, in any matter to be considered or being considered. 3 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies (Pages 3 - 48) To consider report G30/16 of the Deputy Chief Executive which is attached and which is to inform Members of the proposals of the Boundary Commission for England in relation to the 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies and how they will affect Cumbria and Eden in particular, and to determine a means to enable the Council’s response to the consultation on them. RECOMMENDATION: That Members comment upon the proposals of the Boundary Commission with a view to recommending a response to Council. 4 Any Other Items which the Chairman decides are urgent 5 Date of Next Scheduled Meeting Yours faithfully M Neal Deputy Chief Executive (Monitoring Officer) Matthew Neal www.eden.gov.uk Deputy Chief Executive Democratic Services Contact: L Rushen Please Note: Access to the internet in the Council Chamber and Committee room is available via the guest wi-fi