Book XVII License and the Law Editor: Ramon F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Retina Gabriele K

299 12 Retina Gabriele K. Lang and Gerhard K. Lang 12.1 Basic Knowledge The retina is the innermost of three successive layers of the globe. It comprises two parts: ❖ A photoreceptive part (pars optica retinae), comprising the first nine of the 10 layers listed below. ❖ A nonreceptive part (pars caeca retinae) forming the epithelium of the cil- iary body and iris. The pars optica retinae merges with the pars ceca retinae at the ora serrata. Embryology: The retina develops from a diverticulum of the forebrain (proen- cephalon). Optic vesicles develop which then invaginate to form a double- walled bowl, the optic cup. The outer wall becomes the pigment epithelium, and the inner wall later differentiates into the nine layers of the retina. The retina remains linked to the forebrain throughout life through a structure known as the retinohypothalamic tract. Thickness of the retina (Fig. 12.1) Layers of the retina: Moving inward along the path of incident light, the individual layers of the retina are as follows (Fig. 12.2): 1. Inner limiting membrane (glial cell fibers separating the retina from the vitreous body). 2. Layer of optic nerve fibers (axons of the third neuron). 3. Layer of ganglion cells (cell nuclei of the multipolar ganglion cells of the third neuron; “data acquisition system”). 4. Inner plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the second neuron and dendrites of the third neuron). 5. Inner nuclear layer (cell nuclei of the bipolar nerve cells of the second neuron, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells). 6. Outer plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the first neuron and dendrites of the second neuron). -

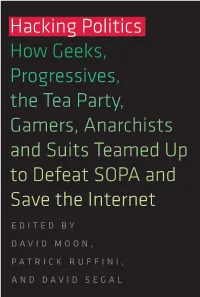

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet EDITED BY DAVID MOON, PATRICK RUFFINI, AND DAVID SEGAL Hacking Politics THE ULTIMATE DOCUMENTATION OF THE ULTIMATE INTERNET KNOCK-DOWN BATTLE! Hacking Politics From Aaron to Zoe—they’re here, detailing what the SOPA/PIPA battle was like, sharing their insights, advice, and personal observations. Hacking How Geeks, Politics includes original contributions by Aaron Swartz, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Lawrence Lessig, Rep. Ron Paul, Reddit’s Alexis Ohanian, Cory Doctorow, Kim Dotcom and many other technologists, activists, and artists. Progressives, Hacking Politics is the most comprehensive work to date about the SOPA protests and the glorious defeat of that legislation. Here are reflections on why and how the effort worked, but also a blow-by-blow the Tea Party, account of the battle against Washington, Hollywood, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that led to the demise of SOPA and PIPA. Gamers, Anarchists DAVID MOON, former COO of the election reform group FairVote, is an attorney and program director for the million-member progressive Internet organization Demand Progress. Moon, Moon, and Suits Teamed Up PATRICK RUFFINI is founder and president at Engage, a leading digital firm in Washington, D.C. During the SOPA fight, he founded “Don’t Censor the to Defeat SOPA and Net” to defeat governmental threats to Internet freedom. Prior to starting Engage, Ruffini led digital campaigns for the Republican Party. Ruffini, Save the Internet DAVID SEGAL, executive director of Demand Progress, is a former Rhode Island state representative. -

Localisation of Visual Hallucinations

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 16 JULY 1977 147 of hypothermia; the duration of cardiac arrest; and the disturbances of sleep or consciousness.4 Hallucinations may be promptness and correctness of treatment. Peterson's pessi- evoked by sensory deprivation, but other factors are usually mistic report from California,8 in which all 15 near-drowned present; thus the "black-patch" delirium that may follow children who had fits, fixed dilated pupils, flaccidity, and loss cataract extraction in the elderly probably results from sensory Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.6080.147 on 16 July 1977. Downloaded from of pain sensation suffered severe anoxic encephalopathy, deprivation and mild senile brain changes and is more frequent may be explained by the high water temperatures there. In when hearing is also impaired.5 warm water the protective effect of hypothermia against brain Hallucinations may be due to focal lesions. Past experiences, damage would be missing. In contrast was the case described the quality of eidetic imagery, and psychodynamic "actors in Trondheim, Norway,9 in which a 5-year-old fell through influence the content of organic hallucinosis,6 and it would be ice in fresh water with an outside temperature of 10° below unwise to lean too heavily on the occurrence and nature of zero centigrade. He was in the water for 22 minutes and was hallucinosis in localising intracranial lesions. Visual hallucina- brought out apparently dead, with widely dilated pupils and tions are a relatively infrequent accompaniment oflesions ofthe bluish white skin. He was warmed up (the method was not calcarine cortex (Brodmann's area 17), which has few thalamo- described) and-despite the risks noted above-was given cortical connections; yet they may occur as a false-localising external cardiac massage without suffering ventricular symptom of frontal or subtentorial lesions. -

Liste Des Indicatifs Téléphoniques Internationaux Par Indicatif 1 Liste Des Indicatifs Téléphoniques Internationaux Par Indicatif

Liste des indicatifs téléphoniques internationaux par indicatif 1 Liste des indicatifs téléphoniques internationaux par indicatif Voici la liste des indicatifs téléphoniques internationaux, permettant d'utiliser les services téléphoniques dans un autre pays. La liste correspond à celle établie par l'Union internationale des télécommunications, dans sa recommandation UIT-T E.164. du 1er février 2004. Liste par pays | Liste par indicatifs Le symbole « + » devant les indicatifs symbolise la séquence d’accès vers l’international. Cette séquence change suivant le pays d’appel ou le terminal utilisé. Depuis la majorité des pays (dont la France), « + » doit être remplacé par « 00 » (qui est le préfixe recommandé). Par exemple, pour appeler en Hongrie (dont l’indicatif international est +36) depuis la France, il faut composer un Indicatifs internationaux par zone numéro du type « 0036######### ». En revanche, depuis les États-Unis, le Canada ou un pays de la zone 1 (Amérique du Nord et Caraïbes), « + » doit être composé comme « 011 ». D’autres séquences sont utilisées en Russie et dans les anciens pays de l’URSS, typiquement le « 90 ». Autrefois, la France utilisait à cette fin le « 19 ». Sur certains téléphones mobiles, il est possible d’entrer le symbole « + » directement en maintenant la touche « 0 » pressée plus longtemps au début du numéro à composer. Mais à partir d’un poste fixe, le « + » n'est pas accessible et il faut généralement taper à la main la séquence d’accès (code d’accès vers l'international) selon le pays d’où on appelle. Zone 0 La zone 0 est pour l'instant réservée à une utilisation future non encore établie. -

Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks: Copyright Guidance Notes (1St Edition)

Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks: Copyright Guidance Notes (1st Edition) Ronan Deazley, Kerry Patterson & Paul Torremans COPYRIGHT IN TITLES AND NEWSPAPER HEADLINES 1 COPYRIGHT IN THE TYPOGRAPHICAL ARRANGEMENT OF PUBLISHED 7 EDITIONS COPYRIGHT IN PSEUDONYMOUS AND ANONYMOUS WORKS 10 COPYRIGHT IN NEWSPAPER ARTICLES 13 COPYRIGHT IN PHOTOGRAPHS: DURATION 19 COPYRIGHT IN PHOTOGRAPHS: OWNERSHIP 26 USING INSUBSTANTIAL PARTS OF A COPYRIGHT PROTECTED WORK 33 COPYRIGHT ACROSS BORDERS 38 MORAL RIGHTS: ATTRIBUTION 45 MORAL RIGHTS: FALSE ATTRIBUTION 52 MORAL RIGHTS: INTEGRITY 55 MORAL RIGHTS: THE RIGHT TO PRIVACY IN CERTAIN PHOTOGRAPHS AND 66 FILMS This is a compendium of the first version of the Guidance Notes on aspects of UK Copyright law that were created as part of Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks, through support by the RCUK funded Centre for Copyright and New Business Models in the Creative Economy (CREATe), AHRC Grant Number AH/K000179/1. The second edition, edited by K. Patterson, can be downloaded individually or as part of the CREATe Working Paper: Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks: Copyright Guidance Notes (2nd Edition) available at www.digitisingmorgan.org/resources. Date Created: January 2017 Cite as: R. Deazley, K. Patterson and P. Torremans, Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks: Copyright Guidance Notes (1st Edition) (2017), available at: www.digitisingmorgan.org/resources COPYRIGHT IN TITLES AND NEWSPAPER HEADLINES Ronan Deazley and Kerry Patterson 1. Introduction What are the implications of the law for digitisation projects involving newspaper headlines and other titles? This guidance explores the legal background to copyright protection in titles and newspaper headlines, with reference to relevant cases. 2. Legislative Context Literary works first received statutory protection in the UK under the Statute of Anne 1710. -

Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction

OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction OPTOMETRY: THE PRIMARY EYE CARE PROFESSION Doctors of optometry are independent primary health care providers who examine, diagnose, treat, and manage diseases and disorders of the visual system, the eye, and associated structures as well as diagnose related systemic conditions. Optometrists provide more than two-thirds of the primary eye care services in the United States. They are more widely distributed geographically than other eye care providers and are readily accessible for the delivery of eye and vision care services. There are approximately 36,000 full-time-equivalent doctors of optometry currently in practice in the United States. Optometrists practice in more than 6,500 communities across the United States, serving as the sole primary eye care providers in more than 3,500 communities. The mission of the profession of optometry is to fulfill the vision and eye care needs of the public through clinical care, research, and education, all of which enhance the quality of life. OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH ACCOMMODATIVE AND VERGENCE DYSFUNCTION Reference Guide for Clinicians Prepared by the American Optometric Association Consensus Panel on Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D., Principal Author Carole R. Burns, O.D. Susan A. Cotter, O.D. Kent M. Daum, O.D., Ph.D. John R. Griffin, M.S., O.D. Mitchell M. Scheiman, O.D. Revised by: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D. December 2010 Reviewed by the AOA Clinical Guidelines Coordinating Committee: David A. -

A Guide to Free Desktop Planetarium Software Resources

Touring the Cosmos through Your Computer: A Guide to Free Desktop Planetarium Software Resources Matthew McCool Southern Polytechnic SU E-mail: [email protected] Summary Key Words This paper reviews ten free software applications for viewing the cosmos Open source astronomy through your computer. Although commercial astronomy software such as Astronomy software Starry Night and Slooh make for excellent viewing of the heavens, they come Digital universes at a price. Fortunately, there is astronomy software that is not only excellent but also free. In this article I provide a brief overview of ten popular free Desktop Planetarium software programs available for your desktop computer. Astronomy Software Table 1. Ten free desktop planetarium applications. Software Computer Platform Web Address Significant strides have been made in free Asynx Windows 2000, XP, NT www.asynx-planetarium.com Desktop Planetarium software for modern commercial computers. Applications range Celestia Linux x86, Mac OS X, Windows www.shatters.net/celestia from the simple to the complex. Many of Deepsky Free Windows 95/98/Me/XP/2000/NT www.download.com/Deepsky- Free/3000-2054_4-10407765.html these astronomy applications can run on several computer platforms (Table 1). DeskNite Windows 95/98/Me/XP/2000/NT www.download.com/DeskNite/ 3000-2336_4-10030582.html Digital Universe Irix, Linux, Mac OS X, Windows www.haydenplanetarium.org/ Most amateur astronomers can meet their universe/download celestial needs using one or more of these Google Earth Linux, Mac OS X, Windows http://earth.google.com/ applications. While applications such as MHX Astronomy Helper Windows Me/XP/98/2000 www.download.com/MHX- Stellarium and Celestia provide a more or Astronomy-Helper/ less comprehensive portal to the heavens, 3000-2054_4-10625264.html more specialised programs such as Solar Solar System 3D Simulator Windows Me/XP/98/2000/NT www.download.com/ System 3D Simulator provide narrow, but Solar-System-3D-Simulator/ focused functionality. -

A Zahlensysteme

A Zahlensysteme Außer dem Dezimalsystem sind das Dual-,dasOktal- und das Hexadezimalsystem gebräuchlich. Ferner spielt das Binär codierte Dezimalsystem (BCD) bei manchen Anwendungen eine Rolle. Bei diesem sind die einzelnen Dezimalstellen für sich dual dargestellt. Die folgende Tabelle enthält die Werte von 0 bis dezimal 255. Be- quemlichkeitshalber sind auch die zugeordneten ASCII-Zeichen aufgeführt. dezimal dual oktal hex BCD ASCII 0 0 0 0 0 nul 11111soh 2102210stx 3113311etx 4 100 4 4 100 eot 5 101 5 5 101 enq 6 110 6 6 110 ack 7 111 7 7 111 bel 8 1000 10 8 1000 bs 9 1001 11 9 1001 ht 10 1010 12 a 1.0 lf 11 101 13 b 1.1 vt 12 1100 14 c 1.10 ff 13 1101 15 d 1.11 cr 14 1110 16 e 1.100 so 15 1111 17 f 1.101 si 16 10000 20 10 1.110 dle 17 10001 21 11 1.111 dc1 18 10010 22 12 1.1000 dc2 19 10011 23 13 1.1001 dc3 20 10100 24 14 10.0 dc4 21 10101 25 15 10.1 nak 22 10110 26 16 10.10 syn 430 A Zahlensysteme 23 10111 27 17 10.11 etb 24 11000 30 18 10.100 can 25 11001 31 19 10.101 em 26 11010 32 1a 10.110 sub 27 11011 33 1b 10.111 esc 28 11100 34 1c 10.1000 fs 29 11101 35 1d 10.1001 gs 30 11110 36 1e 11.0 rs 31 11111 37 1f 11.1 us 32 100000 40 20 11.10 space 33 100001 41 21 11.11 ! 34 100010 42 22 11.100 ” 35 100011 43 23 11.101 # 36 100100 44 24 11.110 $ 37 100101 45 25 11.111 % 38 100110 46 26 11.1000 & 39 100111 47 27 11.1001 ’ 40 101000 50 28 100.0 ( 41 101001 51 29 100.1 ) 42 101010 52 2a 100.10 * 43 101011 53 2b 100.11 + 44 101100 54 2c 100.100 , 45 101101 55 2d 100.101 - 46 101110 56 2e 100.110 . -

32Nd Regional CPA Conference

THE COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION CAYMAN ISLANDS BRANCH VERBATIM REPORT OF THE 32ND REGIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE CARIBBEAN, THE AMERICAS AND THE ATLANTIC REGION Embracing Change in the Way we do Business: Efficient Government GRAND CAYMAN 24TH – 30TH JUNE 2007 Table of Contents OPENING CEREMONY..................................................................................................................1 PRESENTATION OF FLAGS.........................................................................................................1 PRAYERS................................ ............................................. ................................................................2 WELCOME BY HON. EDNA M. MOYLE, JP, MLA, SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, CPA PRESIDENT (CAYMAN ISLANDS).............................2 REMARKS BY HON. D. KURT TIBBETTS, JP, MLA, LEADER OF GOVERNMENT BUSINESS.............................................................................................................................................3 REMARKS BY HON. W. McKEEVA BUSH, OBE, JP, MLA, LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION......................................................................................................................................5 REMARKS BY HON. DR. WILLIAM F. SHIJA, SECRETARY GENERAL (CPA SECRETARIAT LONDON)............................................................................................................6 OPENING OF CONFERENCE BY HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR ...............8 VOTE OF THANKS BY MR. ALFONSO WRIGHT, MLA, -

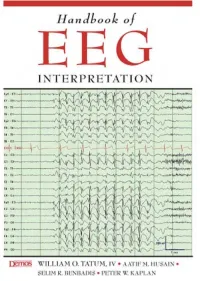

Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION This Page Intentionally Left Blank Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION

Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION This page intentionally left blank Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION William O. Tatum, IV, DO Section Chief, Department of Neurology, Tampa General Hospital Clinical Professor, Department of Neurology, University of South Florida Tampa, Florida Aatif M. Husain, MD Associate Professor, Department of Medicine (Neurology), Duke University Medical Center Director, Neurodiagnostic Center, Veterans Affairs Medical Center Durham, North Carolina Selim R. Benbadis, MD Director, Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Tampa General Hospital Professor, Departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery, University of South Florida Tampa, Florida Peter W. Kaplan, MB, FRCP Director, Epilepsy and EEG, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center Professor, Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Baltimore, Maryland Acquisitions Editor: R. Craig Percy Developmental Editor: Richard Johnson Cover Designer: Steve Pisano Indexer: Joann Woy Compositor: Patricia Wallenburg Printer: Victor Graphics Visit our website at www.demosmedpub.com © 2008 Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved. This book is pro- tected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of EEG interpretation / William O. Tatum IV ... [et al.]. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-933864-11-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-933864-11-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Electroencephalography—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Tatum, William O. [DNLM: 1. Electroencephalography—methods—Handbooks. WL 39 H23657 2007] RC386.6.E43H36 2007 616.8'047547—dc22 2007022376 Medicine is an ever-changing science undergoing continual development. -

The Prescribed West

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2017 The Prescribed West Evan M. Hauser University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Ceramic Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Sculpture Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hauser, Evan M., "The Prescribed West" (2017). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11040. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11040 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PRESCRIBED WEST By EVAN MICHAEL HAUSER Bachelor of Fine Arts, Herron School of Art + Design, Indianapolis, IN, 2014 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Ceramics The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2017 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Julia Galloway, Chair Ceramics Trey Hill, Associate Professor Ceramics Maryann Bonjorni, Professor Drawing H. Rafael Chacon, Professor Art History and Criticism Laurie Yung, Associate Professor Natural Resources Social Science © COPYRIGHT by Evan Michael Hauser 2017 All Rights Reserved ii CONTENTS NARRATIVE ….………………………………………………………………….. 2 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………..... 3 PART I (Predictable Sunset) ……………………………………………………… 4 PART II (Cast Cooler Lids) ……………………………………………………..... 6 PART III (Preservation & Use) …………………………………………..……......8 CONCLUSION …………………………………………………………………. -

2011 Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator's Annual

2011 U.S. INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ENFORCEMENT COORDINATOR ANNUAL REPORT ON INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ENFORCEMENT MARCH 2012 Contents Letter to the President of the United States and to the Congress of the United States 1 Introduction 5 Leading by Example 5 Securing Supply Chains 5 Review of Intellectual Property Laws to Determine Needed Legislative Changes 7 Combating Counterfeit Pharmaceuticals 7 Increasing Transparency 8 Ensuring Efficiency and Coordination 8 Enforcing U S Intellectual Property Rights Internationally 9 A Data-Driven Government 10 Next Steps 11 2011 Implementation of Enforcement Strategy Action Items 13 Leading by Example 13 Establish U.S. Government-Wide Working Group to Prevent U.S. Government Purchase of Counterfeit Products 13 Use of Legal Software by Federal Contractors 14 Increasing Transparency 14 Improved Transparency in Intellectual Property Policy-Making and International Negotiations 14 Increased Information Sharing with Rightholders to Identify Counterfeit Goods 15 Communication with Victims/Rightholders 16 Reporting on Best Practices of Our Trading Partners 18 Identify Foreign Pirate Websites as Part of the Special 301 Process 18 Tracking and Reporting of Enforcement Activities 19 ★ i ★ 2011 IPEC ANNUAL REPORT ON INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ENFORCEMENT Share ITC Exclusion Order Enforcement Data 20 Enhanced Communications to Strengthen Section 337 Enforcement 20 Raising Public Awareness 21 Improving Efficiency of Intellectual Property Enforcement— Using Our Resources as Effectively as Possible 22 Ensuring Efficiency and