Five-Year Clinical Follow-Up of Unprotected Left Main Bifurcation Lesion Stenting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Chinacoalchem

ChinaCoalChem Monthly Report Issue May. 2019 Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved. ChinaCoalChem Issue May. 2019 Table of Contents Insight China ................................................................................................................... 4 To analyze the competitive advantages of various material routes for fuel ethanol from six dimensions .............................................................................................................. 4 Could fuel ethanol meet the demand of 10MT in 2020? 6MTA total capacity is closely promoted ....................................................................................................................... 6 Development of China's polybutene industry ............................................................... 7 Policies & Markets ......................................................................................................... 9 Comprehensive Analysis of the Latest Policy Trends in Fuel Ethanol and Ethanol Gasoline ........................................................................................................................ 9 Companies & Projects ................................................................................................... 9 Baofeng Energy Succeeded in SEC A-Stock Listing ................................................... 9 BG Ordos Started Field Construction of 4bnm3/a SNG Project ................................ 10 Datang Duolun Project Created New Monthly Methanol Output Record in Apr ........ 10 Danhua to Acquire & -

Risk of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Importations Throughout China Prior to the Wuhan Quarantine

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.28.20019299; this version posted February 3, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Title: Risk of 2019 novel coronavirus importations throughout China prior to the Wuhan quarantine 1,+ 2,+ 2 3 4 Authors: Zhanwei Du , Lin Wang , Simon Cauchemez , Xiaoke Xu , Xianwen Wang , 5 1,6* Benjamin J. Cowling , and Lauren Ancel Meyers Affiliations: 1. The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, The United States of America 2. Institut Pasteur, 28 rue du Dr Roux, Paris 75015, France 3. Dalian Minzu University, Dalian 116600, China. 4. Dalian University of Technology, Dalian 116024, China 5. The University of Hong Kong, Sassoon Rd 7, Hong Kong SAR, China 6. Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, New Mexico, The United States of America Corresponding author: Lauren Ancel Meyers Corresponding author email: [email protected] + These first authors contributed equally to this article Abstract On January 23, 2020, China quarantined Wuhan to contain an emerging coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Here, we estimate the probability of 2019-nCoV importations from Wuhan to 369 cities throughout China before the quarantine. The expected risk exceeds 50% in 128 [95% CI 75 186] cities, including five large cities with no reported cases by January 26th. NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. -

Anhui Huainan Urban Water Systems Integrated Rehabilitation Project

China, People's Republic of: Anhui Huainan Urban Water Systems Integrated Rehabilitation Project Project Name Anhui Huainan Urban Water Systems Integrated Rehabilitation Project Project Number 46078-002 Country China, People's Republic of Project Status Active Project Type / Modality Loan of Assistance Technical Assistance Source of Funding / Loan 3054-PRC: Anhui Huainan Urban Water Systems Integrated Rehabilitation Project Amount Ordinary capital resources US$ 150.00 million TA 8491-PRC: Strengthening Urban Flood Management in Huainan Municipality Multi-Donor Trust Fund under the Water Financing Partnership Facility US$ 500,000.00 Strategic Agendas Environmentally sustainable growth Inclusive economic growth Drivers of Change Sector / Subsector Agriculture, natural resources and rural development - Water-based natural resources management Water and other urban infrastructure and services - Urban flood protection - Urban sewerage Gender Equity and Effective gender mainstreaming Mainstreaming Description The impact of the project will be improved urban water environment, public health, and quality of life for urban residents in the Huainan municipality. The outcome of the project will be improved management of surface water resources in the Huainan municipality. The project will have the following components which are all linked to each other: Component 1: Improvement of wastewater collection and transmission systems. This component will include installation of 115.2-kilometer (km) new main wastewater collection and transmission pipes in -

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material The treatment effects of systematic two-stent and provisional stenting techniques in patients with complex coronary bifurcation lesions: Rationale and design of a prospective, randomized, and multicenter DEFINITION Ⅱ Trial Jun-Jie Zhang,1 Xiao-Fei Gao,1 Ya-Ling Han,2 Jing Kan,3 Ling Tao,4 Zhen Ge,1 Damras Tresukosol,5 Shu Lu,6 Li-Kun Ma,7 Feng Li,8 Song Yang,9 Jun Zhang,10 Muhammad Munawar,11 Li Li,12 Rui-Yan Zhang,13 He-Song Zeng,14 Teguh Santoso,15 Ping Xie,16 Ze-Ning Jin,17 Leng Han,18 Wei-Hsian Yin,19 Xue-Song Qian,20 Qi-Hua Li,21 Lang Hong,22 Chotnoparatpat Paiboon,23 Yan Wang,24 Li-Jun Liu,25 Lei Zhou,26 Xue-Ming Wu,27 Shang-Yu Wen,28 Qing-Hua Lu,29 Jun-Qiang Yuan,30 Liang-Long Chen,31 Francesco Lavarra,32 Alfredo E. Rodríguez,33 Li-Min Zhou,34 Shi-Qin Ding,35 Kitigon Vichairuangthum,36 Yuan-Sheng Zhu,37 Meng-Yue Yu,38 Chan Chen,39 Imad Sheiban,40 Yong Xia,41 Yu-Long Tian,42 Zheng-Lu Shang,43 Qing Jiang,44 Yong-Hong Zhen,45 Xin Wang,46 Fei Ye,1 Nai-Liang Tian,1 Song Lin,1 Zhi-Zhong Liu,1 Shao-Liang Chen,1,3* Zhang JJ and Gao XF contributed equally to this work. *Correspondence author: Shao-Liang Chen, Department of cardiology, Nanjing First Hospital, Nanjing Medical University; No. 68 Changle road, 210006 Nanjing, China; Tel & Fax: +86-25-52208048; E-mail: [email protected]. 1Department of Cardiology, Nanjing First Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China; 2Department of Cardiology, The General Hospital of Shenyang Military, Shenyang, China; 3Department of Cardiology, Nanjing Heart Center, Nanjing, -

Coal Quality Characteristics and Distribution Regularity in Depth of Wangfenggang Minefield, Huainan Mining Area

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia Earth and Planetary Science 3 ( 2011 ) 123 – 130 2011 Xican International Conference on Fine Geological Exploration and Groundwater & Gas Hazards Control in Coal Mines Coal Quality Characteristics and Distribution Regularity in Depth of Wangfenggang Minefield, Huainan Mining Area Weihua Ao a,b*, Wenhui Huang a,b, Xiuyi Tang c, Ping Chen c a School of Energy Resources, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing 100083,China b State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Exploitation CUMT, Beijing 100083,China c Anhui University of Science and Technology. Huainan, Anhui 232001, China Abstract This paper studied the deep-seat coal seam in Wangfenggang mine Huainan area, and analyzed the characteristics of coal petrology and coal type distribution, then discussed the influences of regional geothermal history and tectonic subsidence history on regional coal metamorphism process. The results show that a series of bituminous coal band including gas coal, 1/3 coking coal, fat coal and lean coal vertically distributing in the deep seated seam ˉ600m ̚ ˉ1200m). The metamorphism developing tend is same with coal seam structural shape. It presents that the tectonic stress on hydrostatic pressure state can affect coal metamorphism process. It was predicted that the metamorphic type of Wangfenggang minefield is superposition from the effect of energy transformation from tectonic stress on hydrostatic pressure state and katogenic metamorphism, which is long term regional extrusion has promoted and controlled coal metamorphism. The study on coal metamorphism on deep seated seam can be very important on coking coal’s development in China and also contribute to present metamorphism theory. -

Transport Corridors and Regional Balance in China: the Case of Coal Trade and Logistics Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet

Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet To cite this version: Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet. Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics. Journal of Transport Geography, Elsevier, 2014, 40, pp.3-16. halshs-01069149 HAL Id: halshs-01069149 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01069149 Submitted on 28 Sep 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics Dr. Chengjin WANG Key Laboratory of Regional Sustainable Development Modeling Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Email: [email protected] Dr. César DUCRUET1 National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) UMR 8504 Géographie-cités F-75006 Paris, France Email: [email protected] Pre-final version of the paper published in Journal of Transport Geography, special issue on “The Changing Landscapes of Transport and Logistics in China”, Vol. 40, pp. 3-16. Abstract Coal plays a vital role in the socio-economic development of China. Yet, the spatial mismatch between production centers (inland Northwest) and consumption centers (coastal region) within China fostered the emergence of dedicated coal transport corridors with limited alternatives. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 12/Thursday, January 21, 2021

6300 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 12 / Thursday, January 21, 2021 / Notices Dated: January 12, 2021. 9. Linyi Huasheng Yongbin Wood Co., Ltd. International Trade Administration, Jeffrey I. Kessler, 10. Linyi Jiahe Wood Industry Co., Ltd. U.S. Department of Commerce, 1401 11. Linyi Sanfortune Wood Co., Ltd. Assistant Secretary for Enforcement and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, 12. Qingdao Top P&Q International Corp. Compliance. DC 20230; telephone: (202) 482–5305. 13. Shandong Qishan International Trading Appendix I Co., Ltd. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: 14. Shanghai Brightwood Trading Co., Ltd. Background Companies Not Eligible for a Separate Rate 15. Shanghai Futuwood Trading Co., Ltd. 1. Feixian Longteng Wood Co., Ltd. 16. Shanghai Luli Trading Co., Ltd. On July 28, 2020, Commerce 2. Golder International Trade Co., Ltd. 17. Suining Pengxiang Wood Co., Ltd. published the preliminary results of this 3. Highland Industries-Hanlin 18. Suqian Hopeway International Trade Co., administrative review.1 We invited 4. Huainan Mengping Import and Export Co., Ltd. parties to comment on the Preliminary Ltd. 19. Suzhou Oriental Dragon Import and Results. No party submitted comments. 5. Jiangsu High Hope Arser Co., Ltd.27 Export Co., Ltd. 6. Jiangsu Sunwell Cabinetry Co., Ltd. 20. Xuzhou Jiangheng Wood Products Co., Accordingly, the final results remain 7. Jiangsu Top Point International Co., Ltd. Ltd. unchanged from the Preliminary 8. Jiaxing Gsun Imp. & Exp. Co., Ltd. 21. Xuzhou Jiangyang Wood Industries Co., Results. Ltd. 9. Lianyungang Yuantai International Trade Scope of the Order Co., Ltd. 22. Xuzhou Timber International Trade Co., 10. Linyi Bomei Furniture Co., Ltd. Ltd. The scope of the order covers 11. -

The People's Liberation Army's 37 Academic Institutions the People's

The People’s Liberation Army’s 37 Academic Institutions Kenneth Allen • Mingzhi Chen Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN: 9798635621417 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 Design by Heisey-Grove Design All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI Twitter: https://twitter.com/CASI_Research | @CASI_Research Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal, academic, or governmental use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete however, it is requested that reproductions credit the author and China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI). -

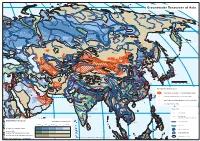

Groundwater Resources Map of Asia (PDF, 1

Groundwater Resources of Asia Murmansk Norilsk Anadyr Arkangelsk + Yakutsk + Saint Petersburg Magadan + Perm Yekaterinburg + Nizhniy Novgorod Moscow Kazan + Chelyabinsk Ufa Omsk + + Novosibirsk + + Samara Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy Irkutsk + + + Astana + + Kyiv + Kharkiv + Volgograd + + Dnipropetrovs'k + Khabarovsk + + Ulaanbaatar Rostov-na-Donu Astrakhan Harbin + Odesa + + + + + + Urumqi Changchun + + Jilin Sapporo + + Almaty T'bilisi Bishkek Vladivostok + Tashkent + Shenyang Istanbul H H Baotou + Huludao Ankara Yerevan Beijing + B Tangshan H + Baku + Bursa + Pyongyang + Dushanbe H + + + + Smyrana Tianjin Dalian + Tabriz Ashgabat H Dongguan Taiyuan+ + B Yantai Seoul Sendai + + + Adana Shijiazhuang + Inch'on Linyi+ + + Zibo Mashhad Lanzhou Jinan Al Mawsil Karaj H + Qingdao + Taegu Taian Taejon Tokyo H HAleppo B + Ulsan Nagoya + H Tehran + + Kyoto + Kabul Zhengzhou + + H Xian + Zaozhuang Kwangju Pusan Hiroshima B Xuzhou H H Beirut H Srinagar + + + H Fukuoka Osaka + Peshawar Suzhou + Damascus Baghdad B Rawalpindi Fuyang + Esfahan + H Gujranwala Tel Aviv-Yafo H Huainan Changzhou + + Amman + + H + B Faisalabad Amritsar Nanjing + H Alexandria + ++ H Jerusalem B B Wuxi Shanghai 0 250 500 750 1000 km H Lahore + Wuhan Suzhou H H Multan Ludhiana Ningbo H H + B Shiraz + Lhasa Chengdu + H H i iB Hangzhou + H iB Cairo H Kuwait Delhi + Meerut Chongqing B B + Changsha + i H H Faridabad Kathmandu Nanchang Special groundwater features H B Wenzhou + B H Jaipur + Agra Lucknow iB i + + Thimphu + + Kanpur Patna Guiyang Fuzhou + + H Dubai Allahabad area of -

KWP China Gas 2004 Final

THE IMPLICATIONS OF CHINA’S GAS EXPANSION TOWARDS THE NATURAL GAS MARKET IN ASIA A CHATHAM HOUSE REPORT FOR JAPAN BANK FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION February 2004 Dr Keun-Wook Paik, Associate Fellow Sustainable Development Programme Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LE www.chathamhouse.org.uk © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2004. This material is offered free of charge for personal and non -commercial use, provided the source is acknowledged. For commercial or any other use, prior written permission must be obtained from the Royal Institute of International Affairs. In no case may this material be altered, sold or rented. The Implications of China’s Gas Expansion towards Natural Gas Market in Asia. Chatham House Report for JBIC, February 2004 Table of Contents 1. China’s Natural Gas Industry ...................................................................................... 1 1.1. A Brief Review on the Natural Gas Industry............................................................ 1 1.1.1. The Role of Natural Gas in China’s Energy Balance....................................... 1 Year .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1.2. Resources.......................................................................................................... 2 1.1.3. Governing bodies and Industry Players ............................................................ 5 1.1.4. Exploration and Production ............................................................................. -

Anthropogenic CH4 Emissions in the Yangtze River Delta Based on a “Top-Down” Method

atmosphere Article Anthropogenic CH4 Emissions in the Yangtze River Delta Based on A “Top-Down” Method Wenjing Huang 1,2, Wei Xiao 1,2, Mi Zhang 1, Wei Wang 1, Jingzheng Xu 3, Yongbo Hu 1, Cheng Hu 1,4, Shoudong Liu 1 and Xuhui Lee 1,2,5,* 1 Yale-NUIST Center on Atmospheric Environment, Nanjing University of Information, Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China; [email protected] (W.H.); [email protected] (W.X.); [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (W.W.); [email protected] (Y.H.); [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (S.L.) 2 NUIST-Wuxi Research Institute, Wuxi 214073, China 3 Radio Science Research Institute Inc., Wuxi 214073, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Soil, Water, and Climate, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA 5 School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (X.L.) Received: 3 March 2019; Accepted: 2 April 2019; Published: 5 April 2019 Abstract: There remains significant uncertainty in the estimation of anthropogenic CH4 emissions at local and regional scales. We used atmospheric CH4 and CO2 concentration data to constrain the anthropogenic CH4 emission in the Yangtze River Delta one of the most populated and economically important regions in China. The observation of atmospheric CH4 and CO2 concentration was carried out from May 2012 to April 2017 at a rural site. A tracer correlation method was used to estimate the anthropogenic CH4 emission in this region, and compared this “top-down” estimate with that obtained with the IPCC inventory method.