An Efficient Recombination System for Chromosome Engineering in Escherichia Coli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci

Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) 32: 123-166. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21775/cimb.032.123 Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci Miao Lu#, Tao Gong#, Anqi Zhang, Boyu Tang, Jiamin Chen, Zhong Zhang, Yuqing Li*, Xuedong Zhou* State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, PR China. #Miao Lu and Tao Gong contributed equally to this work. *Address correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria belonging to the family Streptococcaceae, which are responsible of multiple diseases. Some of these species can cause invasive infection that may result in life-threatening illness. Moreover, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are considerably increasing, thus imposing a global consideration. One of the main causes of this resistance is the horizontal gene transfer (HGT), associated to gene transfer agents including transposons, integrons, plasmids and bacteriophages. These agents, which are called mobile genetic elements (MGEs), encode proteins able to mediate DNA movements. This review briefly describes MGEs in streptococci, focusing on their structure and properties related to HGT and antibiotic resistance. caister.com/cimb 123 Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) Vol. 32 Mobile Genetic Elements Lu et al Introduction Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria widely distributed across human and animals. Unlike the Staphylococcus species, streptococci are catalase negative and are subclassified into the three subspecies alpha, beta and gamma according to the partial, complete or absent hemolysis induced, respectively. The beta hemolytic streptococci species are further classified by the cell wall carbohydrate composition (Lancefield, 1933) and according to human diseases in Lancefield groups A, B, C and G. -

Recombinant DNA and Elements Utilizing Recombinant DNA Such As Plasmids and Viral Vectors, and the Application of Recombinant DNA Techniques in Molecular Biology

Fact Sheet Describing Recombinant DNA and Elements Utilizing Recombinant DNA Such as Plasmids and Viral Vectors, and the Application of Recombinant DNA Techniques in Molecular Biology Compiled and/or written by Amy B. Vento and David R. Gillum Office of Environmental Health and Safety University of New Hampshire June 3, 2002 Introduction Recombinant DNA (rDNA) has various definitions, ranging from very simple to strangely complex. The following are three examples of how recombinant DNA is defined: 1. A DNA molecule containing DNA originating from two or more sources. 2. DNA that has been artificially created. It is DNA from two or more sources that is incorporated into a single recombinant molecule. 3. According to the NIH guidelines, recombinant DNA are molecules constructed outside of living cells by joining natural or synthetic DNA segments to DNA molecules that can replicate in a living cell, or molecules that result from their replication. Description of rDNA Recombinant DNA, also known as in vitro recombination, is a technique involved in creating and purifying desired genes. Molecular cloning (i.e. gene cloning) involves creating recombinant DNA and introducing it into a host cell to be replicated. One of the basic strategies of molecular cloning is to move desired genes from a large, complex genome to a small, simple one. The process of in vitro recombination makes it possible to cut different strands of DNA, in vitro (outside the cell), with a restriction enzyme and join the DNA molecules together via complementary base pairing. Techniques Some of the molecular biology techniques utilized during recombinant DNA include: 1. -

Piggybac Transposase Tools for Genome Engineering.Pdf

piggyBac transposase tools for genome engineering PNAS PLUS Xianghong Lia,b, Erin R. Burnightc, Ashley L. Cooneyd, Nirav Malanie, Troy Bradye, Jeffry D. Sanderf,g, Janice Staberd, Sarah J. Wheelanh, J. Keith Joungf,g, Paul B. McCray, Jr.c,d, Frederic D. Bushmane, Patrick L. Sinnd,1, and Nancy L. Craiga,b,1 aHoward Hughes Medical Institute and bDepartment of Molecular Biology and Genetics, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205; cGenetics Program, Carver College of Medicine, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242; dDepartment of Pediatrics, Carver College of Medicine, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242; eDepartment of Microbiology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; fMolecular Pathology Unit, Center for Computational and Integrative Biology, and Center for Cancer Research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02129; gDepartment of Pathology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; and hDivision of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Department of Oncology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205 Edited by Richard A. Young, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, and approved May 1, 2013 (received for review December 30, 2012) The transposon piggyBac is being used increasingly for genetic stud- site-directed mutagenesis of the PB catalytic domain and isolated − ies. Here, we describe modified versions of piggyBac transposase an excision competent/integration defective (Exc+Int ) PB. We − that have potentially wide-ranging applications, such as reversible also find that introduction of the Exc+Int mutations into a hy- − transgenesis and modified targeting of insertions. piggyBac is dis- peractive version of PB (5, 8, 15) yields an Exc+Int transposase tinguished by its ability to excise precisely, restoring the donor site whose excision frequency is five- to six-fold higher than that of to its pretransposon state. -

Horizontal Gene Transfer

Genetic Variation: The genetic substrate for natural selection Horizontal Gene Transfer Dr. Carol E. Lee, University of Wisconsin Copyright ©2020; Do not upload without permission What about organisms that do not have sexual reproduction? In prokaryotes: Horizontal gene transfer (HGT): Also termed Lateral Gene Transfer - the lateral transmission of genes between individual cells, either directly or indirectly. Could include transformation, transduction, and conjugation. This transfer of genes between organisms occurs in a manner distinct from the vertical transmission of genes from parent to offspring via sexual reproduction. These mechanisms not only generate new gene assortments, they also help move genes throughout populations and from species to species. HGT has been shown to be an important factor in the evolution of many organisms. From some basic background on prokaryotic genome architecture Smaller Population Size • Differences in genome architecture (noncoding, nonfunctional) (regulatory sequence) (transcribed sequence) General Principles • Most conserved feature of Prokaryotes is the operon • Gene Order: Prokaryotic gene order is not conserved (aside from order within the operon), whereas in Eukaryotes gene order tends to be conserved across taxa • Intron-exon genomic organization: The distinctive feature of eukaryotic genomes that sharply separates them from prokaryotic genomes is the presence of spliceosomal introns that interrupt protein-coding genes Small vs. Large Genomes 1. Compact, relatively small genomes of viruses, archaea, bacteria (typically, <10Mb), and many unicellular eukaryotes (typically, <20 Mb). In these genomes, protein-coding and RNA-coding sequences occupy most of the genomic sequence. 2. Expansive, large genomes of multicellular and some unicellular eukaryotes (typically, >100 Mb). In these genomes, the majority of the nucleotide sequence is non-coding. -

Transduction by Bacteriophage Ti * Henry Drexler

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Vol. 66, No. 4, pp. 1083-1088, August 1970 Transduction by Bacteriophage Ti * Henry Drexler DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY, BOWMAN GRAY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE, WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY, WINSTON-SALEM, NORTH CAROLINA Communicated by Edward L. Tatum, May 25, 1970 Abstract. Amber mutants of the virulent coliphage T1 are able to transduce a wide variety of genetic characteristics from permissive to nonpermissive K strains of Escherichia coli. The virulent coliphage T1 is not known to be related to any temperate phage. Certain of the characteristics of T1 seem to be incompatible with its potential existence as a temperate phage; for example, the average latent period for T1 is only 13 min' and about 70% of its DNA is derived from the host.2 In order to demonstrate transduction by T1 it is necessray to provide condi- tions in which potential transductants are able to survive; this is accomplished by using amber mutants of T1 to transduce nonpermissive recipients. Experi- ments which show that T1 is a transducing phage are presented and have been designed chiefly to illustrate the following points: (1) Infection by T1 is able to cause heritable changes in recipients; (2) the genotype of the donor host is im- portant in determining what characteristics can be transferred to recipients; (3) the changes in the recipients are not caused by transformation; and (4) there is a similarity between the transducing activity and the plaque-forming ability of T1 with respect to serology, host range, and density. Materials and Methods. Bacterial strains: The abbreviations and symbols of Demerec et al.3 and Taylor and Trotter4 are used to describe all pertinent genotypes. -

Genetic Engineering and Sustainable Crop Disease Management: Opportunities for Case-By-Case Decision-Making

sustainability Review Genetic Engineering and Sustainable Crop Disease Management: Opportunities for Case-by-Case Decision-Making Paul Vincelli Department of Plant Pathology, 207 Plant Science Building, College of Agriculture, Food and Environment, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40546, USA; [email protected] Academic Editor: Sean Clark Received: 22 March 2016; Accepted: 13 May 2016; Published: 20 May 2016 Abstract: Genetic engineering (GE) offers an expanding array of strategies for enhancing disease resistance of crop plants in sustainable ways, including the potential for reduced pesticide usage. Certain GE applications involve transgenesis, in some cases creating a metabolic pathway novel to the GE crop. In other cases, only cisgenessis is employed. In yet other cases, engineered genetic changes can be so minimal as to be indistinguishable from natural mutations. Thus, GE crops vary substantially and should be evaluated for risks, benefits, and social considerations on a case-by-case basis. Deployment of GE traits should be with an eye towards long-term sustainability; several options are discussed. Selected risks and concerns of GE are also considered, along with genome editing, a technology that greatly expands the capacity of molecular biologists to make more precise and targeted genetic edits. While GE is merely a suite of tools to supplement other breeding techniques, if wisely used, certain GE tools and applications can contribute to sustainability goals. Keywords: biotechnology; GMO (genetically modified organism) 1. Introduction and Background Disease management practices can contribute to sustainability by protecting crop yields, maintaining and improving profitability for crop producers, reducing losses along the distribution chain, and reducing the negative environmental impacts of diseases and their management. -

A Short History of DNA Technology 1865 - Gregor Mendel the Father of Genetics

A Short History of DNA Technology 1865 - Gregor Mendel The Father of Genetics The Augustinian monastery in old Brno, Moravia 1865 - Gregor Mendel • Law of Segregation • Law of Independent Assortment • Law of Dominance 1865 1915 - T.H. Morgan Genetics of Drosophila • Short generation time • Easy to maintain • Only 4 pairs of chromosomes 1865 1915 - T.H. Morgan •Genes located on chromosomes •Sex-linked inheritance wild type mutant •Gene linkage 0 •Recombination long aristae short aristae •Genetic mapping gray black body 48.5 body (cross-over maps) 57.5 red eyes cinnabar eyes 67.0 normal wings vestigial wings 104.5 red eyes brown eyes 1865 1928 - Frederick Griffith “Rough” colonies “Smooth” colonies Transformation of Streptococcus pneumoniae Living Living Heat killed Heat killed S cells mixed S cells R cells S cells with living R cells capsule Living S cells in blood Bacterial sample from dead mouse Strain Injection Results 1865 Beadle & Tatum - 1941 One Gene - One Enzyme Hypothesis Neurospora crassa Ascus Ascospores placed X-rays Fruiting on complete body medium All grow Minimal + amino acids No growth Minimal Minimal + vitamins in mutants Fragments placed on minimal medium Minimal plus: Mutant deficient in enzyme that synthesizes arginine Cys Glu Arg Lys His 1865 Beadle & Tatum - 1941 Gene A Gene B Gene C Minimal Medium + Citruline + Arginine + Ornithine Wild type PrecursorEnz A OrnithineEnz B CitrulineEnz C Arginine Metabolic block Class I Precursor OrnithineEnz B CitrulineEnz C Arginine Mutants Class II Mutants PrecursorEnz A Ornithine -

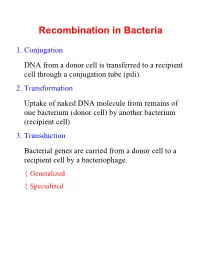

Recombination in Bacteria

Recombination in Bacteria 1. Conjugation DNA from a donor cell is transferred to a recipient cell through a conjugation tube (pili). 2. Transformation Uptake of naked DNA molecule from remains of one bacterium (donor cell) by another bacterium (recipient cell). 3. Transduction Bacterial genes are carried from a donor cell to a recipient cell by a bacteriophage. { Generalized { Specialized Conjugation Ability to conjugate located on the F-plasmid F+ Cells act as donors F- Cells act as recipients F+/F- Conjugation: { F Factor “replicates off” a single strand of DNA. { New strand goes through pili to recipient cell. { New strand is made double stranded. { If entire F-plasmid crosses, then recipient cell becomes F+, otherwise nothing happens Conjugation with Hfr Hfr cell (High Frequency Recombination) cells have F-plasmid integrated into the Chromosome. Integration into the Chromosome is unique for each F-plasmid strain. When F-plasmid material is replicated and sent across pili, Chromosomal material is included. (Figure 6.10 in Klug & Cummings) When chromosomal material is in recipient cell, recombination can occur: { Recombination is double stranded. { Donor genes are recombined into the recipient cell. { Corresponding genes from recipient cell are recombined out of the chromosome and reabsorbed by the cell. Interrupted Mating Mapping 1. Allow conjugation to start Genes closest to the origin of replication site (in the direction of replication) are moved through the pili first. 2. After a set time, interrupt conjugation Only those genes closest to the origin of replication site will conjugate. The long the time, the more that is able to conjugate. 3. -

Microbial Genetics by Dr Preeti Bajpai

Dr. Preeti Bajpai Genes: an overview ▪ A gene is the functional unit of heredity ▪ Each chromosome carry a linear array of multiple genes ▪ Each gene represents segment of DNA responsible for synthesis of RNA or protein product ▪ A gene is considered to be unit of genetic information that controls specific aspect of phenotype DNA Chromosome Gene Protein-1 Prokaryotic Courtesy: Team Shrub https://twitter.com/realscientists/status/927 cell 667237145767937 Genetic exchange within Prokaryotes The genetic exchange occurring in bacteria involve transfers of genes from one bacterium to another. The gene transfer in prokaryotic cells is thus unidirectional and the recombination events usually occur between a fragment of one chromosome (from a donor cell) and a complete chromosome (in a recipient cell) Mechanisms for genetic exchange Bacteria exchange genetic material through three different parasexual processes* namely transformation, conjugation and transduction. *Parasexual process involves recombination of genes from genetically distinct cells occurring without involvement of meiosis and fertilization Principles of Genetics-sixth edition Courtesy: Beatrice the Biologist.com by D. Peter Snustad & Michael J. Simmons (http://www.beatricebiologist.com/2014/08/bacterial-gifts/) Transformation: an introduction Transformation involves the uptake of free DNA molecules released from one bacterium (the donor cell) by another bacterium (the recipient cell). Frederick Griffith discovered transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) in 1928. In his experiments, Griffith used two related strains of bacteria, known as R and S. The R bacteria (nonvirulent) formed colonies, or clumps of related bacteria, that Frederick Griffith 1877-1941 had a rough appearance (hence the abbreviation "R"). The S bacteria (virulent) formed colonies that were rounded and smooth (hence the abbreviation "S"). -

Barriers to Adoption of GM Crops

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Creative Components Dissertations Fall 2021 Barriers to Adoption of GM Crops Madeline Esquivel Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/creativecomponents Part of the Agricultural Education Commons Recommended Citation Esquivel, Madeline, "Barriers to Adoption of GM Crops" (2021). Creative Components. 731. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/creativecomponents/731 This Creative Component is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Creative Components by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Barriers to Adoption of GM Crops By Madeline M. Esquivel A Creative Component submitted to the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Plant Breeding Program of Study Committee: Walter Suza, Major Professor Thomas Lübberstedt Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2021 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3 2. What is a Genetically Modified Organism?................................................................................ 9 2.1 The Development of Modern Varieties and Genetically Modified Crops .......................... 10 2.2 GM vs Traditional Breeding: How Are GM Crops Produced? -

World Resources Institute the Monsanto Company

World Resources Institute Sustainable Enterprise Program A program of the World Resources Institute The Monsanto Company: Quest for Sustainability (A) “Biotechnology represents a potentially sustainable For more than a decade, WRI's solution to the issue, not only of feeding people, but of providing Sustainable Enterprise Program (SEP) the economic growth that people are going to need to escape has harnessed the power of business to poverty…… [Biotechnology] poses the possibility of create profitable solutions to leapfrogging the industrial revolution and moving to a post- environment and development industrial society that is not only economically attractive, but challenges. BELL, a project of SEP, is also environmentally sustainable.i ” focused on working with managers and academics to make companies --Robert Shapiro, CEO, Monsanto Company more competitive by approaching social and environmental challenges as unmet market needs that provide Upon his promotion to CEO of chemical giant The business growth opportunities through Monsanto Company in 1995, Robert Shapiro became a vocal entrepreneurship, innovation, and champion of sustainable development and sought to redefine the organizational change. firm’s business strategy along principles of sustainability. Shapiro’s rhetoric was compelling. He captured analysts’ Permission to reprint this case is attention with the specter of mass hunger and environmental available at the BELL case store. degradation precipitated by rapid population growth and the Additional information on the Case -

Comprehensive Analysis of Mobile Genetic Elements in the Gut Microbiome Reveals Phylum-Level Niche-Adaptive Gene Pools

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/214213; this version posted December 22, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Comprehensive analysis of mobile genetic elements in the gut microbiome 2 reveals phylum-level niche-adaptive gene pools 3 Xiaofang Jiang1,2,†, Andrew Brantley Hall2,3,†, Ramnik J. Xavier1,2,3,4, and Eric Alm1,2,5,* 4 1 Center for Microbiome Informatics and Therapeutics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 5 Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 6 2 Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA 7 3 Center for Computational and Integrative Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard 8 Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA 9 4 Gastrointestinal Unit and Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Massachusetts General 10 Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA 11 5 MIT Department of Biological Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 12 02142, USA 13 † Co-first Authors 14 * Corresponding Author bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/214213; this version posted December 22, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 15 Abstract 16 Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) drive extensive horizontal transfer in the gut microbiome. This transfer 17 could benefit human health by conferring new metabolic capabilities to commensal microbes, or it could 18 threaten human health by spreading antibiotic resistance genes to pathogens. Despite their biological 19 importance and medical relevance, MGEs from the gut microbiome have not been systematically 20 characterized.