Molecular Model for the Transposition and Replication of Bacteriophage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inhibition of Chloroplast DNA Recombination and Repair by Dominant Negative Mutants of Escherichia Coli Reca

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Center for Plant Science Innovation Plant Science Innovation, Center for June 1995 Inhibition of Chloroplast DNA Recombination and Repair by Dominant Negative Mutants of Escherichia coli RecA Heriberto D. Cerutti University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Anita M. Johnson Duke University, Durham, North Carolina John E. Boynton Duke University, Durham, North Carolina Nicholas W. Gillham Duke University, Durham, North Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/plantscifacpub Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Cerutti, Heriberto D.; Johnson, Anita M.; Boynton, John E.; and Gillham, Nicholas W., "Inhibition of Chloroplast DNA Recombination and Repair by Dominant Negative Mutants of Escherichia coli RecA" (1995). Faculty Publications from the Center for Plant Science Innovation. 8. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/plantscifacpub/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Plant Science Innovation, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Center for Plant Science Innovation by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MOLECULAR AND CELLULAR BIOLOGY, June 1995, p. 3003–3011 Vol. 15, No. 6 0270-7306/95/$04.0010 Copyright q 1995, American Society for Microbiology Inhibition of Chloroplast DNA Recombination and Repair by Dominant Negative Mutants of Escherichia coli RecA HERIBERTO CERUTTI, ANITA M. JOHNSON, JOHN E. BOYNTON,* AND NICHOLAS W. GILLHAM Developmental, Cell and Molecular Biology Group, Departments of Botany and Zoology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 Received 7 December 1994/Returned for modification 12 January 1995/Accepted 28 February 1995 The occurrence of homologous DNA recombination in chloroplasts is well documented, but little is known about the molecular mechanisms involved or their biological significance. -

Evaluation of Prophage Gene Revealed Population Variation Of

Evaluation of Prophage Gene Revealed Population Variation of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus’: Bacterial Pathogen of Citrus Huanglongbing (HLB) in Northern Thailand Jutamas Kongjak Chiang Mai University Angsana Akarapisan ( [email protected] ) Chiang Mai University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0506-8675 Research Article Keywords: Citrus, Prophage, Bacteriophage, Huanglongbing, Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus Posted Date: August 24th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-822974/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/15 Abstract ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ is a non-culturable bacterial pathogen, the causal agent of Huanglongbing (HLB, yellow shoot disease, also known as citrus greening disease), a highly destructive disease of citrus (Rutaceae). The pathogen is transmitted by the Asian citrus psyllid: Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. Recent studies, have shown that the HLB pathogen has two prophages, SC1 that has a lytic cycle and SC2 associated with bacterial virulence. This study aimed to search for SC1 and SC2 prophages of HLB in mandarin orange, sweet orange, bitter orange, kumquat, key lime, citron, caviar lime, kar lime, pomelo and orange jasmine from ve provinces in Northern Thailand. A total of 216 samples collected from Northern Thailand during 2019 and 2020 were studied. The results revealed that 62.04% (134/216) citrus samples were infected with the ‘Ca. L. asiaticus’ the bacterial pathogen associated with citrus HLB. The prophage particles are important genetic elements of bacterial genomes that are involved in lateral gene transfer, pathogenicity, environmental adaptation and interstrain genetic variability. Prophage particles were evaluated in the terminase gene of SC1 and SC2-type prophages. -

Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci

Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) 32: 123-166. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21775/cimb.032.123 Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci Miao Lu#, Tao Gong#, Anqi Zhang, Boyu Tang, Jiamin Chen, Zhong Zhang, Yuqing Li*, Xuedong Zhou* State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, PR China. #Miao Lu and Tao Gong contributed equally to this work. *Address correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria belonging to the family Streptococcaceae, which are responsible of multiple diseases. Some of these species can cause invasive infection that may result in life-threatening illness. Moreover, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are considerably increasing, thus imposing a global consideration. One of the main causes of this resistance is the horizontal gene transfer (HGT), associated to gene transfer agents including transposons, integrons, plasmids and bacteriophages. These agents, which are called mobile genetic elements (MGEs), encode proteins able to mediate DNA movements. This review briefly describes MGEs in streptococci, focusing on their structure and properties related to HGT and antibiotic resistance. caister.com/cimb 123 Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) Vol. 32 Mobile Genetic Elements Lu et al Introduction Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria widely distributed across human and animals. Unlike the Staphylococcus species, streptococci are catalase negative and are subclassified into the three subspecies alpha, beta and gamma according to the partial, complete or absent hemolysis induced, respectively. The beta hemolytic streptococci species are further classified by the cell wall carbohydrate composition (Lancefield, 1933) and according to human diseases in Lancefield groups A, B, C and G. -

The Bacteriophage Mu Lysis System--A New Mechanism of Host

BIOCELL Tech Science Press 2021 45(5): 1175-1186 The bacteriophage mu lysis system–A new mechanism of host lysis? SAIKAT SAMANTA1,#;ASHISH RANJAN SHARMA2,#;ABINIT SAHA1;MANOJ KUMAR SINGH1;ARPITA DAS1; MANOJIT BHATTACHARYA3;RUDRA PRASAD SAHA1,*;SANG-SOO LEE2,*;CHIRANJIB CHAKRABORTY1,* 1 Department of Biotechnology, School of Life Science & Biotechnology, Adamas University, Kolkata, 700126, India 2 Institute for Skeletal Aging & Orthopedic Surgery, Hallym University-Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital, Chuncheon-si, 24252, Korea 3 Department of Zoology, Fakir Mohan University, Balasore, 56020, India Key words: Bacteriophage Mu, Host cell lysis, Endolysin, Holin, Spanin Abstract: Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria and can choose any one of the two alternative pathways for infection, i.e., lysis or lysogeny. Phage lysis is one of the conventional biological processes required to spread infection from one bacterium to another. Our analysis suggests that in the paradigm bacteriophage Mu, six proteins might be involved in host cell lysis. Mu has a broad host range, and Mu-like phages were found in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. An analysis of the genomes of Mu and Mu-like phages could be useful in elucidating the lysis mechanism in this group of phages. A detailed review of the various mechanisms of phage lysis and different proteins associated with the process will help researchers understand the phage biology and their life cycle in different bacteria. The recent increase in the number of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of bacteria and the usual long-term nature of new drug development has encouraged scientists to look for alternative strategies like phage therapy and the discovery of new lysis mechanisms. -

State of Prophage Mu DNA Upon Induction (Bacteriophage Mu/Bacteriophage X/DNA Insertion/DNA Excision/Transposable Elements) E

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 74, No. 8, pp. 3143-3147, August 1977 Biochemistry State of prophage Mu DNA upon induction (bacteriophage Mu/bacteriophage X/DNA insertion/DNA excision/transposable elements) E. LjUNGQUIST AND A. I. BUKHARI Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, New York 11724 Communicated by J. D. Watson, April 18, 1977 ABSTRACT We have compared the process of prophage different host sequences. Yet, a form of Mu DNA free of host A induction with that of prophage Mu. According to the DNA has remained undetected. Campbell model, rescue of A DNA from the host DNA involves In its continuous association with host DNA, Mu resembles reversal of X integration such that the prophage DNA is excised from the host chromosome. We have monitored this event by another class of insertion elements, referred to as the trans- locating the prophage DNA with a technique in which DNA of posable elements. The transposable elements are specific the lysogenic cells is cleaved with a restriction endonuclease stretches of DNA that can be translocated from one position to and fractionated in agarose gels. The DNA fragments are de- another in host DNA (7). Mu undergoes multiple rounds of natured in gels, transferred to a nitrocellulose paper, and hy- transposition during its growth, far exceeding the transposition bridized with 32P-labeled mature phage DNA. The fragments frequency of the bonafide transposable elements. When a Mu containing prophage DNA become visible after autoradiogra- lysogen, carrying a single Mu prophage at a given site on the phy. Upon prophage A induction, the phage-host junction fragments disappear and the fragment containing the A att site host chromosome, is induced, many copies of Mu DNA are appears. -

Horizontal Gene Transfer

Genetic Variation: The genetic substrate for natural selection Horizontal Gene Transfer Dr. Carol E. Lee, University of Wisconsin Copyright ©2020; Do not upload without permission What about organisms that do not have sexual reproduction? In prokaryotes: Horizontal gene transfer (HGT): Also termed Lateral Gene Transfer - the lateral transmission of genes between individual cells, either directly or indirectly. Could include transformation, transduction, and conjugation. This transfer of genes between organisms occurs in a manner distinct from the vertical transmission of genes from parent to offspring via sexual reproduction. These mechanisms not only generate new gene assortments, they also help move genes throughout populations and from species to species. HGT has been shown to be an important factor in the evolution of many organisms. From some basic background on prokaryotic genome architecture Smaller Population Size • Differences in genome architecture (noncoding, nonfunctional) (regulatory sequence) (transcribed sequence) General Principles • Most conserved feature of Prokaryotes is the operon • Gene Order: Prokaryotic gene order is not conserved (aside from order within the operon), whereas in Eukaryotes gene order tends to be conserved across taxa • Intron-exon genomic organization: The distinctive feature of eukaryotic genomes that sharply separates them from prokaryotic genomes is the presence of spliceosomal introns that interrupt protein-coding genes Small vs. Large Genomes 1. Compact, relatively small genomes of viruses, archaea, bacteria (typically, <10Mb), and many unicellular eukaryotes (typically, <20 Mb). In these genomes, protein-coding and RNA-coding sequences occupy most of the genomic sequence. 2. Expansive, large genomes of multicellular and some unicellular eukaryotes (typically, >100 Mb). In these genomes, the majority of the nucleotide sequence is non-coding. -

Philympics 2021: Prophage Predictions Perplex Programs

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.03.446868; this version posted June 3, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Philympics 2021: Prophage 2 Predictions Perplex Programs 3 Michael J. Roach1*, Katelyn McNair2, Sarah K. Giles1, Laura Inglis1, Evan Pargin1, Przemysław 4 Decewicz3, Robert A. Edwards1 5 1. Flinders Accelerator for Microbiome Exploration, Flinders University, 5042, SA, Australia 6 2. Computational Sciences Research Center, San Diego State University, San Diego, 92182, CA, USA 7 3. Department of Environmental Microbiology and Biotechnology, Institute of Microbiology, Faculty 8 of Biology, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, 02-096, Poland 9 10 *Corresponding Author: [email protected] 11 12 Abstract 13 Most bacterial genomes contain integrated bacteriophages—prophages—in various states of decay. 14 Many are active and able to excise from the genome and replicate, while others are cryptic 15 prophages, remnants of their former selves. Over the last two decades, many computational tools 16 have been developed to identify the prophage components of bacterial genomes, and it is a 17 particularly active area for the application of machine learning approaches. However, progress is 18 hindered and comparisons thwarted because there are no manually curated bacterial genomes that 19 can be used to test new prophage prediction algorithms. 20 Here, we present a library of gold-standard bacterial genome annotations that include manually 21 curated prophage annotations, and a computational framework to compare the predictions from 22 different algorithms. -

Transduction by Bacteriophage Ti * Henry Drexler

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Vol. 66, No. 4, pp. 1083-1088, August 1970 Transduction by Bacteriophage Ti * Henry Drexler DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY, BOWMAN GRAY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE, WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY, WINSTON-SALEM, NORTH CAROLINA Communicated by Edward L. Tatum, May 25, 1970 Abstract. Amber mutants of the virulent coliphage T1 are able to transduce a wide variety of genetic characteristics from permissive to nonpermissive K strains of Escherichia coli. The virulent coliphage T1 is not known to be related to any temperate phage. Certain of the characteristics of T1 seem to be incompatible with its potential existence as a temperate phage; for example, the average latent period for T1 is only 13 min' and about 70% of its DNA is derived from the host.2 In order to demonstrate transduction by T1 it is necessray to provide condi- tions in which potential transductants are able to survive; this is accomplished by using amber mutants of T1 to transduce nonpermissive recipients. Experi- ments which show that T1 is a transducing phage are presented and have been designed chiefly to illustrate the following points: (1) Infection by T1 is able to cause heritable changes in recipients; (2) the genotype of the donor host is im- portant in determining what characteristics can be transferred to recipients; (3) the changes in the recipients are not caused by transformation; and (4) there is a similarity between the transducing activity and the plaque-forming ability of T1 with respect to serology, host range, and density. Materials and Methods. Bacterial strains: The abbreviations and symbols of Demerec et al.3 and Taylor and Trotter4 are used to describe all pertinent genotypes. -

First Description of a Temperate Bacteriophage (Vb Fhim KIRK) of Francisella Hispaniensis Strain 3523

viruses Article First Description of a Temperate Bacteriophage (vB_FhiM_KIRK) of Francisella hispaniensis Strain 3523 Kristin Köppen 1,†, Grisna I. Prensa 1,†, Kerstin Rydzewski 1, Hana Tlapák 1, Gudrun Holland 2 and Klaus Heuner 1,* 1 Centre for Biological Threats and Special Pathogens, Cellular Interactions of Bacterial Pathogens, ZBS 2, Robert Koch Institute, 13353 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] (K.K.); [email protected] (G.I.P.); [email protected] (K.R.); [email protected] (H.T.) 2 Centre for Biological Threats and Special Pathogens, Advanced Light and Electron Microscopy, ZBS 4, Robert Koch Institute, D-13353 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-30-18754-2226 † Both authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Here we present the characterization of a Francisella bacteriophage (vB_FhiM_KIRK) includ- ing the morphology, the genome sequence and the induction of the prophage. The prophage sequence (FhaGI-1) has previously been identified in F. hispaniensis strain 3523. UV radiation induced the prophage to assemble phage particles consisting of an icosahedral head (~52 nm in diameter), a tail of up to 97 nm in length and a mean width of 9 nm. The double stranded genome of vB_FhiM_KIRK contains 51 open reading frames and is 34,259 bp in length. The genotypic and phylogenetic analysis indicated that this phage seems to belong to the Myoviridae family of bacteriophages. Under the Citation: Köppen, K.; Prensa, G.I.; conditions tested here, host cell (Francisella hispaniensis 3523) lysis activity of KIRK was very low, and Rydzewski, K.; Tlapák, H.; Holland, the phage particles seem to be defective for infecting new bacterial cells. -

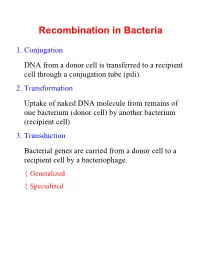

Recombination in Bacteria

Recombination in Bacteria 1. Conjugation DNA from a donor cell is transferred to a recipient cell through a conjugation tube (pili). 2. Transformation Uptake of naked DNA molecule from remains of one bacterium (donor cell) by another bacterium (recipient cell). 3. Transduction Bacterial genes are carried from a donor cell to a recipient cell by a bacteriophage. { Generalized { Specialized Conjugation Ability to conjugate located on the F-plasmid F+ Cells act as donors F- Cells act as recipients F+/F- Conjugation: { F Factor “replicates off” a single strand of DNA. { New strand goes through pili to recipient cell. { New strand is made double stranded. { If entire F-plasmid crosses, then recipient cell becomes F+, otherwise nothing happens Conjugation with Hfr Hfr cell (High Frequency Recombination) cells have F-plasmid integrated into the Chromosome. Integration into the Chromosome is unique for each F-plasmid strain. When F-plasmid material is replicated and sent across pili, Chromosomal material is included. (Figure 6.10 in Klug & Cummings) When chromosomal material is in recipient cell, recombination can occur: { Recombination is double stranded. { Donor genes are recombined into the recipient cell. { Corresponding genes from recipient cell are recombined out of the chromosome and reabsorbed by the cell. Interrupted Mating Mapping 1. Allow conjugation to start Genes closest to the origin of replication site (in the direction of replication) are moved through the pili first. 2. After a set time, interrupt conjugation Only those genes closest to the origin of replication site will conjugate. The long the time, the more that is able to conjugate. 3. -

Microbial Genetics by Dr Preeti Bajpai

Dr. Preeti Bajpai Genes: an overview ▪ A gene is the functional unit of heredity ▪ Each chromosome carry a linear array of multiple genes ▪ Each gene represents segment of DNA responsible for synthesis of RNA or protein product ▪ A gene is considered to be unit of genetic information that controls specific aspect of phenotype DNA Chromosome Gene Protein-1 Prokaryotic Courtesy: Team Shrub https://twitter.com/realscientists/status/927 cell 667237145767937 Genetic exchange within Prokaryotes The genetic exchange occurring in bacteria involve transfers of genes from one bacterium to another. The gene transfer in prokaryotic cells is thus unidirectional and the recombination events usually occur between a fragment of one chromosome (from a donor cell) and a complete chromosome (in a recipient cell) Mechanisms for genetic exchange Bacteria exchange genetic material through three different parasexual processes* namely transformation, conjugation and transduction. *Parasexual process involves recombination of genes from genetically distinct cells occurring without involvement of meiosis and fertilization Principles of Genetics-sixth edition Courtesy: Beatrice the Biologist.com by D. Peter Snustad & Michael J. Simmons (http://www.beatricebiologist.com/2014/08/bacterial-gifts/) Transformation: an introduction Transformation involves the uptake of free DNA molecules released from one bacterium (the donor cell) by another bacterium (the recipient cell). Frederick Griffith discovered transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) in 1928. In his experiments, Griffith used two related strains of bacteria, known as R and S. The R bacteria (nonvirulent) formed colonies, or clumps of related bacteria, that Frederick Griffith 1877-1941 had a rough appearance (hence the abbreviation "R"). The S bacteria (virulent) formed colonies that were rounded and smooth (hence the abbreviation "S"). -

Comprehensive Analysis of Mobile Genetic Elements in the Gut Microbiome Reveals Phylum-Level Niche-Adaptive Gene Pools

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/214213; this version posted December 22, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Comprehensive analysis of mobile genetic elements in the gut microbiome 2 reveals phylum-level niche-adaptive gene pools 3 Xiaofang Jiang1,2,†, Andrew Brantley Hall2,3,†, Ramnik J. Xavier1,2,3,4, and Eric Alm1,2,5,* 4 1 Center for Microbiome Informatics and Therapeutics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 5 Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 6 2 Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA 7 3 Center for Computational and Integrative Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard 8 Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA 9 4 Gastrointestinal Unit and Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Massachusetts General 10 Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA 11 5 MIT Department of Biological Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 12 02142, USA 13 † Co-first Authors 14 * Corresponding Author bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/214213; this version posted December 22, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 15 Abstract 16 Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) drive extensive horizontal transfer in the gut microbiome. This transfer 17 could benefit human health by conferring new metabolic capabilities to commensal microbes, or it could 18 threaten human health by spreading antibiotic resistance genes to pathogens. Despite their biological 19 importance and medical relevance, MGEs from the gut microbiome have not been systematically 20 characterized.