Shepherd School Symphony Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pavel Lisitsian Discography by Richard Kummins

Pavel Lisitsian Discography By Richard Kummins e-mail: [email protected] Rev - 17 June 2014 Composer Selection Other artists Date Lang Record # The capital city of the country (Stolitsa Agababov rodin) 1956 Rus 78 USSR 41366 (1956) LP Melodiya 14305/6 (1964) LP Melodiya M10 45467/8 (1984) CD Russian Disc 15022 (1994) MP3 RMG 1637 (2005 - Song Listen, maybe, Op 49 #2 (Paslushai, byt Anthology Vol 1) Arensky mozhet) Andrei Mitnik, piano 1951 Rus MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) 78 USSR 14626 (1947) LP Vocal Record Collector's Armenian (trad) Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1947 Arm Society 1992 Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1948 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) Armenian girls (Hayotz akhchikner) 1960 (San LP New York Records PL 101 Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Maro Ajemian, piano Francisco) Arm (1960) Crane (Groong) 1960 (San LP New York Records PL 101 Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) Maro Ajemian, piano Francisco) Arm (1960) Russian Folk Instrument Orchestra - Crane (Groong) Central TV and All-Union Radio LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) (arranged by Aleksandr Dolukhanian) - Vladimir Fedoseyev 1968 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) LP DKS 6228 (1955) Armenian (trad) Dogwood forest (Lyut kizil usta tvoi) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1955 Arm MP3 RMG 1766 (2006) Dream (Yeraz) (arranged by Aleksandr LP Melodiya 45465/6 (1984) Armenian (trad) Dolukhanian) Matvei Sakharov, piano 1948 Arm MP3 RMG -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

Everyday Stalinism Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times Soviet Russia in the 1930S Sheila Fitzpatrick

Everyday Stalinism Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times Soviet Russia in the 1930s Sheila Fitzpatrick Sheila Fitzpatrick is an Australian-American historian. She is Honorary Professor at the University of Sydney with her primary speciality being the history of modern Russia. Her recent work has focused on Soviet social and cultural history in the Stalin period, particularly everyday practices and social identity. From the archives of the website The Master and Margarita http://www.masterandmargarita.eu Webmaster Jan Vanhellemont Klein Begijnhof 6 B-3000 Leuven +3216583866 +32475260793 Everyday Stalinism Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times Soviet Russia in the 1930s Sheila Fitzpatrick Copyright © 1999 by Oxford University Press, Inc. First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 1999 To My Students Table of Contents Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Milestones Stories A Note on Class 1. “The Party Is Always Right” Revolutionary Warriors Stalin’s Signals Bureaucrats and Bosses A Girl with Character 2. Hard Times Shortages Miseries of Urban Life Shopping as a Survival Skill Contacts and Connections 3. Palaces on Monday Building a New World Heroes The Remaking of Man Mastering Culture 4. The Magic Tablecloth Images of Abundance Privilege Marks of Status Patrons and Clients 5. Insulted and Injured Outcasts Deportation and Exile Renouncing the Past Wearing the Mask 6. Family Problems Absconding Husbands The Abortion Law The Wives’ Movement 7. Conversations and Listeners Listening In Writing to the Government Public Talk Talking Back 8. A Time of Troubles The Year 1937 Scapegoats and “The Usual Suspects” Spreading the Plague Living Through the Great Purges Conclusion Notes Bibliography Contents This book has been a long time in the making - almost twenty years, if one goes back to its first incarnation; ten years in its present form. -

Kentridge's Nose*

Kentridge’s Nose* MARIA GOUGH Gogol’s grotesque raged around us; what were we to understand as farce, what as prophecy? The incredible orchestral combinations, texts seemingly unthinkable to sing . t he unhabitual rhythms . t he incorporat - ing of the apparently anti-poetic, anti-musical, vulgar, but what was in reality the intonation and parody of real life—all this was an assault on conventionality. —Grigorii Kozintsev (1969), on the 1930 Leningrad premiere of The Nose If one holds onto the discoveries, the risks and inven - tions of the Russian avant-garde . one also has to find a place not simply to acknowledge, but to house the faith animating the work of its members—their belief in a transformed society. —William Kentridge (2008) In his quest for an all-out renewal of operatic form, Peter Gelb, the General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera in New York since 2006, packed the 2009 –2010 season with eight new productions, essentially bringing to a close the reign of Franco Zeffirelli, whose florid, love-it or hate-it Neapolitanesque scenography has more or less dominated the proscenium for decades, at least with respect to the Italian reper - toire. With just one exception, all the new additions to the Met’s inventory this past * Sincere thanks to Tom Cummins for generously enabling my graduate seminar to attend the premiere of The Nose at the Met, to Jodi Hauptman for arranging entry to the performance of William Kentridge’s theatrical monologue I Am Not Me, The Horse Is Not Mine at the Museum of Modern Art, to Leah Dickerman and the October editors for inviting the present reflection, and to Eve-Laure Moros Ortega, Ian Forster, Art 21 Inc., Marian Goodman Gallery, Sam Johnson, Hugh Truslow, and Adam Lehner for various forms of invaluable assistance. -

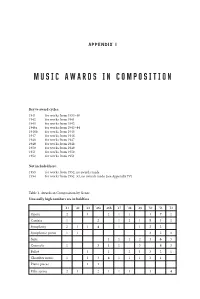

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

Cello Concerto (1990)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers A-G RUSTAM ABDULLAYEV (b. 1947, UZBEKISTAN) Born in Khorezm. He studied composition at the Tashkent Conservatory with Rumil Vildanov and Boris Zeidman. He later became a professor of composition and orchestration of the State Conservatory of Uzbekistan as well as chairman of the Composers' Union of Uzbekistan. He has composed prolifically in most genres including opera, orchestral, chamber and vocal works. He has completed 4 additional Concertos for Piano (1991, 1993, 1994, 1995) as well as a Violin Concerto (2009). Piano Concerto No. 1 (1972) Adiba Sharipova (piano)/Z. Khaknazirov/Uzbekistan State Symphony Orchestra ( + Zakirov: Piano Concerto and Yanov-Yanovsky: Piano Concertino) MELODIYA S10 20999 001 (LP) (1984) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where his composition teacher was Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. Piano Concerto in E minor (1976) Alexander Tutunov (piano)/ Marlan Carlson/Corvallis-Oregon State University Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Trio, Aria for Viola and Piano and 10 Romances) ALTARUS 9058 (2003) Aria for Violin and Chamber Orchestra (1973) Mikhail Shtein (violin)/Alexander Polyanko/Minsk Chamber Orchestra ( + Vagner: Clarinet Concerto and Alkhimovich: Concerto Grosso No. 2) MELODIYA S10 27829 003 (LP) (1988) MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Concertos A-G ISIDOR ACHRON (1891-1948) Piano Concerto No. -

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich)

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich) (b Sontsovka, Bakhmutsk region, Yekaterinoslav district, Ukraine, 11/23 April 1891; d Moscow, 5 March 1953). Russian composer and pianist. He began his career as a composer while still a student, and so had a deep investment in Russian Romantic traditions – even if he was pushing those traditions to a point of exacerbation and caricature – before he began to encounter, and contribute to, various kinds of modernism in the second decade of the new century. Like many artists, he left his country directly after the October Revolution; he was the only composer to return, nearly 20 years later. His inner traditionalism, coupled with the neo-classicism he had helped invent, now made it possible for him to play a leading role in Soviet culture, to whose demands for political engagement, utility and simplicity he responded with prodigious creative energy. In his last years, however, official encouragement turned into persecution, and his musical voice understandably faltered. 1. Russia, 1891–1918. 2. USA, 1918–22. 3. Europe, 1922–36. 4. The USSR, 1936–53. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY DOROTHEA REDEPENNING © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online 1. Russia, 1891–1918. (i) Childhood and early works. (ii) Conservatory studies and first public appearances. (iii) The path to emigration. © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online Prokofiev, Sergey, §1: Russia: 1891–1918 (i) Childhood and early works. Prokofiev grew up in comfortable circumstances. His father Sergey Alekseyevich Prokofiev was an agronomist and managed the estate of Sontsovka, where he had gone to live in 1878 with his wife Mariya Zitkova, a well-educated woman with a feeling for the arts. -

Kabalevsky Was Born in St Petersburg on 30 December 1904 and Died in Moscow on 14 February 1987 at the Age of 83

DMITRI KABALEVSKY SIKORSKI MUSIKVERLAGE HAMBURG SIK 4/5654 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD by Maria Kabalevskaya ...................... 4 VORWORT ....................................... 6 INTRODUCTION by Tatjana Frumkis .................... 8 EINFÜHRUNG .................................. 10 AWARDS AND PRIZES ............................ 13 CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF WORKS .............. 15 SYSTEMATIC INDEX OF WORKS Stage Works ..................................... 114 Orchestral Works ................................. 114 Instrumental Soloist and Orchestra .................... 114 Wind Orchestra ................................... 114 Solo Voice(s) and Orchestra ......................... 115 Solo Voice(s), Choir and Orchestra .................... 115 Choir and Orchestra ............................... 115 Solo Voice(s), Choir and Piano ....................... 115 Choir and Piano .................................. 115 Voice(s) a cappella ................................ 117 Voice(s) and Instruments ............................ 117 Voice and Piano .................................. 117 Piano Solo ....................................... 118 Piano Four Hands ................................. 119 Instrumental Chamber Works ........................ 119 Incidental Music .................................. 120 Film Music ...................................... 120 Arrangements .................................... 121 INDEX Index of Opus Numbers ............................ 122 Works Without Opus Numbers ....................... 125 Alphabetic Index of Works ......................... -

The Nineteenth-Century Russian Operatic Roots of Prokofyev’S

THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY RUSSIAN OPERATIC ROOTS OF PROKOFYEV’S WAR AND PEACE by TERRY LYNN DEAN, JR. (Under the Direction of David Edwin Haas) ABSTRACT More than fifty years after Prokofyev’s death, War and Peace remains a misunderstood composition. While there are many reasons why the opera remains misunderstood, the primary reason for this is the opera’s genesis in Stalinist Russia and his obligation to uphold the “life-affirming” principles of the pro-Soviet aesthetic, Socialist Realism, by drawing inspiration from the rich heritage “Russian classical” opera—specifically the works of Glinka, Chaikovsky, and Musorgsky. The primary intent of this dissertation is to provide new perspectives on War and Peace by examining the relationship between the opera and the nineteenth-century Russian opera tradition. By exploring such a relationship, one can more clearly understand how nineteenth-century Russian operas had a formative effect on Prokofyev’s opera aesthetic. An analysis of the impact of the Russian operatic tradition on War and Peace will also provide insights into the ways in which Prokofyev responded to official Soviet demands to uphold the canon of nineteenth-century Russian opera as models for contemporary composition and to implement aspects of 19th-century compositional practice into 20th-century compositions. Drawing upon the critical theories of Soviet musicologist Boris Asafyev, this study demonstrates that while Prokofyev maintained his distinct compositional voice, he successfully aligned his work with the nineteenth-century tradition. Moreover, the study suggests that Prokofyev’s solution to rendering Tolstoy’s novel as an opera required him to utilize a variety of traits characteristic of the nineteenth-century Russian opera tradition, resulting in a work that is both eclectic in musical style and dramaturgically effective. -

Shostakovich / Дмитрий Шостакович (1906–1975) «И Со Мною Моя “Седьмая”» Смысл, Сюжет, Форма

V A L E S Y R M M A P A R H R T ’ Y O I S D N IN E A Y SK CH R N Y OR G SH O NIN G O 7 ‘LE H E STAKOVIC RGIE V 2 SYMPHONY NO 7 Mariinsky DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH / Дмитрий ШостАкович (1906–1975) «И СО МНОЮ МОЯ “СЕДЬМАЯ”» Смысл, сюжет, форма. Вначале Шостакович хотел сделать Леонид Гаккель свою Седьмую одночастной симфонической поэмой. В Symphony No 7 in C major, Op. 60 / Симфония № 7, «Ленинградская», до мажор, соч. 60 итоге предпочел традиционный четырехчастный цикл, но в нем оказалась громадная первая часть (Allegretto, 1 i. Allegretto – Moderato – Adagio 28’45’’ Война. Россия. Вторая мировая война, которую в России называют Великой Отечественной, стоила нашему народу по времени – треть симфонии), соединившая главные 2 ii. Moderato (poco Allegretto) 15’30’’ двадцати семи миллионов жизней (и эта цифра не является смыслы этого сочинения, представившая его звуковой состав. Бесконфликтная мажорная экспозиция – это 3 iii. Adagio – Largo – Moderato risoluto 19’03’’ окончательной). Страна пережила крупнейшую гекатомбу в своей истории. И тем более неожиданными выглядят строки мирная жизнь, но исследователи давно заметили, что уже 4 iv. Allegro non troppo – Moderato 19’03’’ русской поэтессы военных лет Ольги Берггольц: «Такими мы здесь формируется «тема нашествия», что зло уже явилось. счастливыми бывали, //Такой свободой бурною дышали, //Что Начинается двенадцатиминутный эпизод, единогласно внуки позавидовали б нам». В те годы наш мир упростился, в называемый «нашествием». На протяжении 356 тактов Total duration / Общее время звучания 82’21’’ нем остались лишь «мы» и «они» (враги, грозившие стучит малый барабан. «Тема нашествия» запоминается уничтожением), а если воспользоваться словами филолога сразу, так она проста. -

Tocc0324dbook.Pdf

MATVEY NIKOLAEVSKY: A LIGHT-MUSIC MASTER REDISCOVERED by Anthony Phillips History – not least the tangled cultural history of Soviet Russia – has not been kind to the gifted Matvey Nikolaevsky. Yet on 27 May 1938, at the peak of his popularity in the 1920s and ’30s, an astonishing array of the cream of Soviet musical life filled the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatoire to celebrate the 35th anniversary of Nikolaevsky’s artistic career – although his handwritten autobiographical résumé reveals that his working life had begun much earlier, at the age of twelve. His career embraced distinction as pianist, as composer of a string of universally known and loved ballads, popular songs, dance numbers, orchestral marches and genre pieces, and as a much-respected piano teacher with several books of keyboard technique instruction to his credit. One at least such tutor, entitled Conservatoire [i.e., ‘correct’] Positioning of the Hand on the Piano, first appearing in 1917, has been republished countless times, is in print and is widely used to this day. Among the famous names from the world of music, opera and ballet taking part in the 1938 gala concert were the composers Reinhold Glière and Sergei Vasilenko; the conductors Nikolai Golovanov (music director of the Bolshoi Theatre), Yuri Feier, Alexander Melik-Pashayev and Samuil Samosud; the pianist Alexander Goldenweiser, then Rector of the Moscow Conservatoire; the prodigy violinist Busya Goldstein; a clutch of the Soviet Union’s most celebrated singers: the sopranos Antonina Nezhdanova and Maria -

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Born in St. Petersburg. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13 and studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. His graduation piece, the Symphony No. 1, gave him immediate fame and from there he went on to become the greatest composer during the Soviet Era of Russian history despite serious problems with the political and cultural authorities. He also concertized as a pianist and taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He was a prolific composer whose compositions covered almost all genres from operas, ballets and film scores to works for solo instruments and voice. Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor with Trumpet and String Orchestra, Op. 35 (1933) Dmitri Alexeyev (piano)/Philip Jones (trumpet)/Jerzy Maksymiuk/English Chamber Orchestra ( + Piano Concerto No. 2, Unforgettable Year 1919, Gadfly: Suite, Tahiti Trot, Suites for Jazz Orchestra Nos. 1 and 2) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE 382234-2 (2007) Victor Aller (piano)/Murray Klein (trumpet)/Felix Slatkin/Concert Arts Orchestra ( + Hindemith: The Four Temperaments) CAPITOL P 8230 (LP) (1953) Leif Ove Andsnes (piano)/Håkan Hardenberger (trumpet)/Paavo Järvi/City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra ( + Britten: Piano Concerto and Enescu: Legende) EMI CLASSICS 56760-2 (1999) Annie d' Arco (piano)/Maurice André (trumpet)/Jean-François Paillard/Orchestre de Chambre Jean François Paillard (included in collection: "Maurice André Edition - Volume