Careful Design Delivers Halogen-Like LED Dimming (MAGAZINE)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Lecture 26

PHYS 445 Lecture 26 - Black-body radiation I 26 - 1 Lecture 26 - Black-body radiation I What's Important: · number density · energy density Text: Reif In our previous discussion of photons, we established that the mean number of photons with energy i is 1 n = (26.1) i eß i - 1 Here, the questions that we want to address about photons are: · what is their number density · what is their energy density · what is their pressure? Number density n Eq. (26.1) is written in the language of discrete states. The first thing we need to do is replace the sum by an integral over photon momentum states: 3 S i ® ò d p Of course, it isn't quite this simple because the density-of-states issue that we introduced before: for every spin state there is one phase space state for every h 3, so the proper replacement more like 3 3 3 S i ® (1/h ) ò d p ò d r The units now work: the left hand side is a number, and so is the right hand side. But this expression ignores spin - it just deals with the states in phase space. For every photon momentum, there are two ways of arranging its polarization (i.e., the orientation of its electric or magnetic field vectors): where the photon momentum vector is perpendicular to the plane. Thus, we have 3 3 3 S i ® (2/h ) ò d p ò d r. (26.2) Assuming that our system is spatially uniform, the position integral can be replaced by the volume ò d 3r = V. -

Article Soot Photometer Using Supervised Machine Learning

Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 3885–3906, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-3885-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Classification of iron oxide aerosols by a single particle soot photometer using supervised machine learning Kara D. Lamb1,2 1Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA 2NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Chemical Sciences Division, Boulder, CO, USA Correspondence: Kara D. Lamb ([email protected]) Received: 15 March 2019 – Discussion started: 22 March 2019 Revised: 20 June 2019 – Accepted: 21 June 2019 – Published: 15 July 2019 Abstract. Single particle soot photometers (SP2) use laser- each class are compared with the true class for those particles induced incandescence to detect aerosols on a single particle to estimate generalization performance. While the specific basis. SP2s that have been modified to provide greater spec- class approach performed well for rBC and Fe3O4 (≥ 99 % tral contrast between their narrow and broad-band incandes- of these aerosols are correctly identified), its classification of cent detectors have previously been used to characterize both other aerosol types is significantly worse (only 47 %–66 % refractory black carbon (rBC) and light-absorbing metallic of other particles are correctly identified). Using the broader aerosols, including iron oxides (FeOx). However, single par- class approach, we find a classification accuracy of 99 % for ticles cannot be unambiguously identified from their incan- FeOx samples measured in the laboratory. The method al- descent peak height (a function of particle mass) and color lows for classification of FeOx as anthropogenic or dust-like ratio (a measure of blackbody temperature) alone. -

Introduction 1

1 1 Introduction . ex arte calcinati, et illuminato aeri [ . properly calcinated, and illuminated seu solis radiis, seu fl ammae either by sunlight or fl ames, they conceive fulgoribus expositi, lucem inde sine light from themselves without heat; . ] calore concipiunt in sese; . Licetus, 1640 (about the Bologna stone) 1.1 What Is Luminescence? The word luminescence, which comes from the Latin (lumen = light) was fi rst introduced as luminescenz by the physicist and science historian Eilhardt Wiede- mann in 1888, to describe “ all those phenomena of light which are not solely conditioned by the rise in temperature,” as opposed to incandescence. Lumines- cence is often considered as cold light whereas incandescence is hot light. Luminescence is more precisely defi ned as follows: spontaneous emission of radia- tion from an electronically excited species or from a vibrationally excited species not in thermal equilibrium with its environment. 1) The various types of lumines- cence are classifi ed according to the mode of excitation (see Table 1.1 ). Luminescent compounds can be of very different kinds: • Organic compounds : aromatic hydrocarbons (naphthalene, anthracene, phenan- threne, pyrene, perylene, porphyrins, phtalocyanins, etc.) and derivatives, dyes (fl uorescein, rhodamines, coumarins, oxazines), polyenes, diphenylpolyenes, some amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine), etc. + 3 + 3 + • Inorganic compounds : uranyl ion (UO 2 ), lanthanide ions (e.g., Eu , Tb ), doped glasses (e.g., with Nd, Mn, Ce, Sn, Cu, Ag), crystals (ZnS, CdS, ZnSe, CdSe, 3 + GaS, GaP, Al 2 O3 /Cr (ruby)), semiconductor nanocrystals (e.g., CdSe), metal clusters, carbon nanotubes and some fullerenes, etc. 1) Braslavsky , S. et al . ( 2007 ) Glossary of terms used in photochemistry , Pure Appl. -

Lecture 17 : the Cosmic Microwave Background

Let’s think about the early Universe… Lecture 17 : The Cosmic ! From Hubble’s observations, we know the Universe is Microwave Background expanding ! This can be understood theoretically in terms of solutions of GR equations !Discovery of the Cosmic Microwave ! Earlier in time, all the matter must have been Background (ch 14) squeezed more tightly together ! If crushed together at high enough density, the galaxies, stars, etc could not exist as we see them now -- everything must have been different! !The Hot Big Bang This week: read Chapter 12/14 in textbook 4/15/14 1 4/15/14 3 Let’s think about the early Universe… Let’s think about the early Universe… ! From Hubble’s observations, we know the Universe is ! From Hubble’s observations, we know the Universe is expanding expanding ! This can be understood theoretically in terms of solutions of ! This can be understood theoretically in terms of solutions of GR equations GR equations ! Earlier in time, all the matter must have been squeezed more tightly together ! If crushed together at high enough density, the galaxies, stars, etc could not exist as we see them now -- everything must have been different! ! What was the Universe like long, long ago? ! What were the original contents? ! What were the early conditions like? ! What physical processes occurred under those conditions? ! How did changes over time result in the contents and structure we see today? 4/15/14 2 4/15/14 4 The Poetic Version ! In a brilliant flash about fourteen billion years ago, time and matter were born in a single instant of creation. -

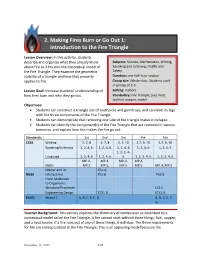

2. Making Fires Burn Or Go out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle

2. Making Fires Burn or Go Out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle Lesson Overview: In this activity, students describe and organize what they already know Subjects: Science, Mathematics, Writing, about fire so it fits into the conceptual model of Speaking and Listening, Health and the Fire Triangle. They examine the geometric Safety stability of a triangle and how that property Duration: one half-hour session applies to fire. Group size: Whole class. Students work in groups of 2-3. Lesson Goal: Increase students’ understanding of Setting: Indoors how fires burn and why they go out. Vocabulary: Fire Triangle, fuel, heat, ignition, oxygen, model Objectives: • Students can construct a triangle out of toothpicks and gumdrops, and can label its legs with the three components of the Fire Triangle. • Students can demonstrate that removing one side of the triangle makes it collapse. • Students can identify the component(s) of the Fire Triangle that are removed in various scenarios, and explain how this makes the fire go out. Standards: 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th CCSS Writing 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 10 2,7, 9, 10 2,7, 9, 10 Speaking/Listening 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, Language 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, Math MP.5 MP.5, MP.5 MP.5 MP.4, MP.5 Matter and Its PS1.A, NGSS Interactions PS1.B PS1.B From Molecules to Organisms: Structure/Processes LS1.C Engineering Design ETS1.B ETS1.B EEEGL Strand 1 A, B, C, E, F, G A, B, C, E, F, G Teacher Background: This activity explores the chemistry of combustion as described by a conceptual model called the Fire Triangle. -

Energy Efficiency Lighting Hearing Committee On

S. HRG. 110–195 ENERGY EFFICIENCY LIGHTING HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION TO RECEIVE TESTIMONY ON THE STATUS OF ENERGY EFFICIENT LIGHT- ING TECHNOLOGIES AND ON S. 2017, THE ENERGY EFFICIENT LIGHT- ING FOR A BRIGHTER TOMORROW ACT SEPTEMBER 12, 2007 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39–385 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:58 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 040443 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\DOCS\39385.XXX SENERGY2 PsN: MONICA COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico, Chairman DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho RON WYDEN, Oregon LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD BURR, North Carolina MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JIM DEMINT, South Carolina MARIA CANTWELL, Washington BOB CORKER, Tennessee KEN SALAZAR, Colorado JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama BLANCHE L. LINCOLN, Arkansas GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon BERNARD SANDERS, Vermont JIM BUNNING, Kentucky JON TESTER, Montana MEL MARTINEZ, Florida ROBERT M. SIMON, Staff Director SAM E. FOWLER, Chief Counsel FRANK MACCHIAROLA, Republican Staff Director JUDITH K. PENSABENE, Republican Chief Counsel (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:58 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 040443 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 G:\DOCS\39385.XXX SENERGY2 PsN: MONICA C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Bingaman, Hon. -

Measurement of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation at 19 Ghz

Measurement of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation at 19 GHz 1 Introduction Measurements of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation dominate modern experimental cosmology: there is no greater source of information about the early universe, and no other single discovery has had a greater impact on the theories of the formation of the cosmos. Observation of the CMB confirmed the Big Bang model of the origin of our universe and gave us a look into the distant past, long before the formation of the very first stars and galaxies. In this lab, we seek to recreate this founding pillar of modern physics. The experiment consists of a temperature measurement of the CMB, which is actually “light” left over from the Big Bang. A radiometer is used to measure the intensity of the sky signal at 19 GHz from the roof of the physics building. A specially designed horn antenna allows you to observe microwave noise from isolated patches of sky, without interference from the relatively hot (and high noise) ground. The radiometer amplifies the power from the horn by a factor of a billion. You will calibrate the radiometer to reduce systematic effects: a cryogenically cooled reference load is periodically measured to catch changes in the gain of the amplifier circuit over time. 2 Overview 2.1 History The first observation of the CMB occurred at the Crawford Hill NJ location of Bell Labs in 1965. Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, intending to do research in radio astronomy at 21 cm wavelength using a special horn antenna designed for satellite communications, noticed a background noise signal in all of their radiometric measurements. -

Black Body Radiation

BLACK BODY RADIATION hemispherical Stefan-Boltzmann law This law states that the energy radiated from a black body is proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature. Wien Displacement Law FormulaThe Wien's Displacement Law provides the wavelength where the spectral radiance has maximum value. This law states that the black body radiation curve for different temperatures peaks at a wavelength inversely proportional to the temperature. Maximum wavelength = Wien's displacement constant / Temperature The equation is: λmax= b/T Where: λmax: The peak of the wavelength b: Wien's displacement constant. (2.9*10(−3) m K) T: Absolute Temperature in Kelvin. Emissive power The value of the Stefan-Boltzmann constant is approximately 5.67 x 10 -8 watt per meter squared per kelvin to the fourth (W · m -2 · K -4 ). If the radiation emitted normal to the surface and the energy density of radiation is u, then emissive power of the surface E=c u If the radiation is diffuse Emitted uniformly in all directions 1 E= 푐푢 4 Thermal radiation exerts pressure on the surface on which they are Incident. If the intensity of directed beam of radiations incident normally to The surface is I 퐼 Then Pressure P=u= 푐 If the radiation is diffused 1 P= 푢 3 The value of the constant is approximately 1.366 kilowatts per square metre. When the emissivity of non-black surface is constant at all temperatures and throughout the entire range of wavelength, the surface is called Gray Body. PROBLEMS 1. The temperature of a person’s skin is 350 C. -

Class 12 I : Blackbody Spectra

Class 12 Spectra and the structure of atoms Blackbody spectra and Wien’s law Emission and absorption lines Structure of atoms and the Bohr model I : Blackbody spectra Definition : The spectrum of an object is the distribution of its observed electromagnetic radiation as a function of wavelength or frequency Particularly important example… A blackbody spectrum is that emitted from an idealized dense object in “thermal equilibrium” You don’t have to memorize this! h=6.626x10-34 J/s -23 kB=1.38x10 J/K c=speed of light T=temperature 1 2 Actual spectrum of the Sun compared to a black body 3 Properties of blackbody radiation… The spectrum peaks at Wien’s law The total power emitted per unit surface area of the emitting body is given by finding the area under the blackbody curve… answer is Stephan-Boltzmann Law σ =5.67X10-8 W/m2/K4 (Stephan-Boltzmann constant) II : Emission and absorption line spectra A blackbody spectrum is an example of a continuum spectrum… it is smooth as a function of wavelength Line spectra: An absorption line is a sharp dip in a (continuum) spectrum An emission line is a sharp spike in a spectrum Both phenomena are caused by the interaction of photons with atoms… each atoms imprints a distinct set of lines in a spectrum The precise pattern of emission/absorption lines tells you about the mix of elements as well as temperature and density 4 Solar spectrum… lots of absorption lines 5 Kirchhoffs laws: A solid, liquid or dense gas produces a continuous (blackbody) spectrum A tenuous gas seen against a hot -

Biofluorescence

Things That Glow In The Dark Classroom Activities That Explore Spectra and Fluorescence Linda Shore [email protected] “Hot Topics: Research Revelations from the Biotech Revolution” Saturday, April 19, 2008 Caltech-Exploratorium Learning Lab (CELL) Workshop Special Guest: Dr. Rusty Lansford, Senior Scientist and Instructor, Caltech Contents Exploring Spectra – Using a spectrascope to examine many different kinds of common continuous, emission, and absorption spectra. Luminescence – A complete description of many different examples of luminescence in the natural and engineered world. Exploratorium Teacher Institute Page 1 © 2008 Exploratorium, all rights reserved Exploring Spectra (by Paul Doherty and Linda Shore) Using a spectrometer The project Star spectrometer can be used to look at the spectra of many different sources. It is available from Learning Technologies, for under $20. Learning Technologies, Inc., 59 Walden St., Cambridge, MA 02140 You can also build your own spectroscope. http://www.exo.net/~pauld/activities/CDspectrometer/cdspectrometer.html Incandescent light An incandescent light has a continuous spectrum with all visible colors present. There are no bright lines and no dark lines in the spectrum. This is one of the most important spectra, a blackbody spectrum emitted by a hot object. The blackbody spectrum is a function of temperature, cooler objects emit redder light, hotter objects white or even bluish light. Fluorescent light The spectrum of a fluorescent light has bright lines and a continuous spectrum. The bright lines come from mercury gas inside the tube while the continuous spectrum comes from the phosphor coating lining the interior of the tube. Exploratorium Teacher Institute Page 2 © 2008 Exploratorium, all rights reserved CLF Light There is a new kind of fluorescent called a CFL (compact fluorescent lamp). -

Peter Scicluna – Systematic Effects in Dust-Mass Determinations

The other side of the equation Systematic effects in the determination of dust masses Peter Scicluna ASIAA JCMT Users’ Meeting, Nanjing, 13th February 2017 Peter Scicluna JCMT Users’ Meeting, Nanjing, 13th February 2017 1 / 9 Done for LMC (Reibel+ 2012), SMC (Srinivasan+2016) Total dust mass ∼ integrated dust production over Hubble time What about dust destruction? Dust growth in the ISM? Are the masses really correct? The dust budget crisis: locally Measure dust masses in FIR/sub-mm Measure dust production in MIR Gordon et al., 2014 Peter Scicluna JCMT Users’ Meeting, Nanjing, 13th February 2017 2 / 9 What about dust destruction? Dust growth in the ISM? Are the masses really correct? The dust budget crisis: locally Measure dust masses in FIR/sub-mm Measure dust production in MIR Done for LMC (Reibel+ 2012), SMC (Srinivasan+2016) Total dust mass ∼ integrated dust production over Hubble time Gordon et al., 2014 Peter Scicluna JCMT Users’ Meeting, Nanjing, 13th February 2017 2 / 9 Dust growth in the ISM? Are the masses really correct? The dust budget crisis: locally Measure dust masses in FIR/sub-mm Measure dust production in MIR Done for LMC (Reibel+ 2012), SMC (Srinivasan+2016) Total dust mass ∼ integrated dust production over Hubble time What about dust destruction? Gordon et al., 2014 Peter Scicluna JCMT Users’ Meeting, Nanjing, 13th February 2017 2 / 9 How important are supernovae? Are there even enough metals yet? Dust growth in the ISM? Are the masses really correct? The dust budget crisis: at high redshift Rowlands et al., 2014 Measure -

Exterior Lighting Guide for Federal Agencies

EXTERIOR LIGHTING GUIDE FOR FederAL AgenCieS SPONSORS TABLE OF CONTENTS The U.S. Department of Energy, the Federal Energy Management Program, page 02 INTRODUctiON page 44 EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), and the California Lighting Plasma Lighting page 04 REASONS FOR OUTDOOR Technology Center (CLTC) at the University of California, Davis helped fund and Networked Lighting LiGHtiNG RETROFitS create the Exterior Lighting Guide for Federal Agencies. Photovoltaic (PV) Lighting & Systems Energy Savings LBNL conducts extensive scientific research that impacts the national economy at Lowered Maintenance Costs page 48 EXTERIOR LiGHtiNG RETROFit & $1.6 billion a year. The Lab has created 12,000 jobs nationally and saved billions of Improved Visual Environment DESIGN BEST PRActicES dollars with its energy-efficient technologies. Appropriate Safety Measures New Lighting System Design Reduced Lighting Pollution & Light Trespass Lighting System Retrofit CLTC is a research, development, and demonstration facility whose mission is Lighting Design & Retrofit Elements page 14 EVALUAtiNG THE CURRENT to stimulate, facilitate, and accelerate the development and commercialization of Structure Lighting LIGHtiNG SYSTEM energy-efficient lighting and daylighting technologies. This is accomplished through Softscape Lighting Lighting Evaluation Basics technology development and demonstrations, as well as offering outreach and Hardscape Lighting Conducting a Lighting Audit education activities in partnership with utilities, lighting