Stadium and Premises; Material Change of Circumstances; Relegation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customer Charter 2019/20

Wigan Athletic Football Club Customer Charter CUSTOMER CHARTER 2019/20 WE WIGAN Wigan Athletic Football Club Customer Charter INTRODUCTION Welcome to Wigan Athletic Football Club (“the club”) Customer Charter, in which we detail our policies and procedures which affect you as a supporter or visiting supporter. We will explain how we will meet the objectives of our charter throughout the season in relation to ticketing, supporter consultation, discrimination, policing, merchandise and community interaction. The club is committed to ensuring that the objectives are delivered. Page 2 Wigan Athletic Football Club Customer Charter CONTENTS 1.0 CUSTOMER SERVICE COMMITMENT 4 5.0 MEMBERSHIP SCHEMES AND BENEFITS 18 (A) Official Supporters Club 18 2.0 CONSULTATION AND INFORMATION 5 (B) Latics For Life 19 (C) Mascots 20 3.0 TICKETING 6 (A) General Information 6 6.0 MERCHANDISE 21 (B) Ticket Prices 7 (A) General 21 (i) Season Cards 7 (B) Refund Policy 21 (ii) Match Day Ticket Prices 8 (iii) Match Day Hospitality 8 7.0 EQUALITY AND DIVERSITY 22 (C) Away Matches 10 (D) Cup Competitions 10 8.0 WIGAN ATHLETIC COMMUNITY TRUST 23 (E) Returns and Refunds 10 (F) Lost or Stolen Tickets 11 9.0 SAFEGUARDING 24 (G) Accommodating Away Supporters 11 10.0 GOOD CAUSES, CHARITIES 25 4.0 GENERAL STADIUM INFORMATION 12 AND SIGNED MERCHANDISE (A) Non-Permitted Items 12 (B) Smoking Policy 12 11.0 DATA PROTECTION POLICY 26 (C) Standing Policy 12 (D) Ground Regulations 12 12.0 CUSTOMER SERVICES CONTACT 27 (E) Safety Policy 13 (F) Stewards 13 13.0 COMPLAINTS POLICY 28 (G) Catering 15 (H) Cleanliness 15 14.0 CLUB CONTACTS 31 (I) Directions and Parking 16 (J) Visiting Supporters 17 (K) Accessibility Information 17 Please note that the information contained herein is correct at the time of production. -

Felly's Football Tour Introduction 3

Felly’s Football Tour Sprint/Summer 2021 (tbc) Fundraising for Fellysfund in memory of our good friend The Motivation To Turf Moor To the University of Bolton Stadium Supporting Felly’s Fund To Deepdale To Goodison Park To Boundary Park Felly's Football Tour Introduction 3 Redwood Events have been arranging charity walks and cycle events since 2007 and have recently started to work with the Darby Rimmer MND Foundation. This has given us a great exposure to, and understanding of, the challenges that the Motor Neurone Disease can bring. Life changes very quickly for those diagnosed with MND and for their families. The average life expectancy for someone with Motor Neurone Disease is just 2-5 years from the onset of symptoms. A third of people diagnosed will die within a year and half within 2 years. It’s a 1/300 lifetime risk in the UK of being diagnosed with MND. That’s 3 children in each and every school today. There is no known cause of MND and there is no cure or effective treatment, it’s always fatal. When Paul Stanway talked to us about the great work they have done in memory of their great friend Felly, we were very keen to help. Felly’s Football Tour will combine a 131 mile continuous walking tour from Liverpool FC (Felly’s favourite team) to Fleetwood Town FC calling at fifteen other football grounds in between. This is a journey of 130 miles. After a short break for breakfast, the walking will give to cycling as riders will then head north from Fleetwood Town to Barrow AFC via Morecambe FC, a journey of 73 miles. -

International Entertainment Corporation 國 有 公司

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should consult your licensed securities dealer, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional advisers. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in International Entertainment Corporation (the ‘‘Company’’), you should at once hand this circular and the accompanying form of proxy to the purchaser(s) or the transferee(s) or to the bank, licensed securities dealer or registered institution in securities or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was affected for transmission to the purchaser(s) or the transferee(s). Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. INTERNATIONAL ENTERTAINMENT CORPORATION 國 際 娛 樂 有 限 公 司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 01009) MAJOR AND CONNECTED TRANSACTIONS AND NOTICE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENERAL MEETING Financial adviser to the Company Independent Financial Adviser to the Independent Board Committee and the Independent Shareholders AnoticeconveningtheEGM(asdefinedherein)oftheCompanytobeheldat11:30a.m.onFriday,29May2020 at Song, Yuan & Ming Rooms, The Dynasty Club, 7th Floor, South West Tower, Convention Plaza, 1 Harbour Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong is set out on pages EGM-1 to EGM-3 of this circular. -

Round 232021

FRONTTHE ROW ROUND 23 2021 VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 24 PARTY AT THE BACK Backs and halves dominate the Run rabbit run rookie class of 2021 TheBiggestTiger zones in on a South Sydney superstar! INSIDE: ROUND 23 PROGRAM - SQUAD LISTS, PREVIEWS & HEAD TO HEAD STATS, R22 REVIEWED LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 24 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 24 Tim Costello From the editor 3 It's been an interesting year for break-out stars. Were painfully aware of the lack of lower-grade rugby league that's been able Feature Rookie Class of 2021 4-5 to be played in the last 18 months, and the impact that's going to have on development pathways in all states - particularly in History Tommy Anderson 6-7 New South Wales. The results seems to be that we're getting a lot more athletic, backline-suited players coming through, with Feature The Run Home 8 new battle-hardened forwards making the grade few and far between. Over the page Rob Crosby highlights the Rookie Class Feature 'Trell' 9 of 2021 - well worth a read. NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders 10 Also this week thanks to Andrew Ferguson, we have a footy history piece on Tommy Anderson - an inaugural South Sydney GAME DAY · NRL Round 23 11-27 player who was 'never the same' after facing off against Dally Messenger. The BiggestTiger's weekly illustration shows off the LU Team Tips 11 speed and skill of Latrell Mitchell, and we update the run home to the finals with just three games left til the September action THU Gold Coast v Melbourne 12-13 kicks off. -

Round 252021

FRONTTHE ROW ROUND 25 2021 VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 26 Finals bound A Newcastle duo celebrates clearing a path to September footy GAME CHANGERS 'CONTESTED' BOMBS, DOUBLE MOVEMENTS, DROP BALLS... THE RULES THAT REALLY SHOULD CHANGE INSIDE: ROUND 25 PROGRAM - SQUAD LISTS, PREVIEWS & HEAD TO HEAD STATS, R24 REVIEWED LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 26 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 26 Tim Costello From the editor 3 Something always happens when the Roosters and Rabbitohs face off. Just a law of physics really. Plenty of controversy Feature Rule changes 4-5 this week which saw Latrell Mitchell slammed with a 6 week suspension for a reckless high shot on opposing centre Joey News NRL statements 6 Manu. With Mitchell not sent off and the subsequent unravelling of the contest, Roosters coach Trent Robinson unloaded on Feature Knights celebration 7 the officials involved in the match, and himself then hit with a breach notice from the NRL for his post-match comments. QRL Teamlists - ISC R16, Colts R13 8 Henry Perenara was also stood down from Bunker duties for the weekend and subsequently won't be manning the screens this QRL results 9 round either. NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders 10 This week we've changed tack a little bit - we've got Rick Edgerton tossing up some ideas for discussion, given the NRL's GAME DAY · NRL Round 25 11-27 recent propensity for controversial rule changes.His ideas are designed to clear up grey areas around aerial contests, double LU Team Tips 11 movements and knock-ons - check them out and let us know THU Canberra v Sydney Roosters 12-13 what you think! FRI Cronulla v Melbourne 14-15 Meanwhile we surge into the final round with plenty still on the line for most clubs. -

Manchester United V Wigan Athletic FA Community Shield Sponsored by Mcdonald’S

Manchester United v Wigan Athletic FA Community Shield sponsored by McDonald’s Wembley Stadium Sunday 11 August 2013 Kick-off 2pm FA Community Shield Contents Introduction by David Barber, FA Historian 1 Background 2 Shield results 3-5 Shield appearances 5 Head-to-head 7 Manager profiles 8 Premier League 2012/13 League table 10 Team statistic review 11 Manchester United player stats 12 Wigan player stats 13 Goals breakdown 14 Results 2012-13 15-16 FA Cup 2012/13 Results 17 Officials 18 Referee statistics & Discipline record 19 Rules & Regulations 20-21 Manchester United v Wigan Athletic, Wembley Stadium, Sunday 11 August 2013, Kick-off 2pm FA Community Shield Introduction by David Barber, FA Historian Manchester United, Premier League champions for the 13th time, meet Wigan Athletic, FA Cup-winners for the first time, in the traditional season curtain-raiser at Wembley Stadium. The match will be the 91st time the Shield has been contested. The only match ever to go to a replay was the very first - in 1908. No club has a Shield pedigree like Manchester United. They were its first winners and have now clocked up a record 15 successes. They have shared the Shield an additional four times and have featured in a total of 28 contests. Wigan Athletic, by contrast, were a non-League club until 1978 and are playing the first Shield match in their 81-year history. The FA Charity Shield, its name until 2002, evolved from the Sheriff of London Shield - an annual fixture between the leading professional and amateur clubs of the time. -

Kuwaittimes 21-2-2018.Qxp Layout 1

JAMADA ALTHANI 5, 1439 AH WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 2018 Max 22º 32 Pages Min 10º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17463 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Two more embassy officials Syria pounds rebel enclave, AUB reports net profit Messi breaks Chelsea duck; 5 recalled over maid’s death 6 sends fighters to face Turkey 17 of $618.7m for 2017 16 5-star Bayern romp home Minister extends amnesty for residence violators till April 22 Curbs relaxed on absconding domestics • MP warns PM against raising charges By B Izzak In a related decision, the director Abbas calls for Mideast general of the residence department KUWAIT: Interior Minister Sheikh yesterday issued a decision allowing peace conference in Khaled Al-Jarrah Al-Sabah yesterday maids registered by their sponsors as extended the amnesty for residence vio- absconding to transfer to a new sponsor lators by two more months till April 22. without the prior consent of the original rare UN speech The extension came in an official circular employer. Previously, workers and maids signed by the minister yesterday follow- registered by their employers as UNITED NATIONS: Palestinian nism emanating from an interna- ing reports that as many as 50,000 absconding or runaways were not leader Mahmoud Abbas yester- tional conference,” Abbas said. expatriate residency violators have ben- allowed to get their residence trans- day called for an international President Donald Trump’s deci- efitted from the amnesty that was to end ferred without the consent of their spon- conference to be held by mid- sion to move the US embassy to on Feb 23. -

St. Helens R.F.C

MEDIA BOOK 2013 ST. HELENS R.F.C. 4. Club contact information. 5. Press arrangements. 6. Honours. 7. Squad numbers. 9. Paul Wellens & Ade Gardner. CONTENTS 10. Jordan Turner & Sia Soliola. 11. Francis Meli & Lance Hohaia. 12. Jonny Lomax & Josh Perry. 13. James Roby & Louie McCarthy-Scarsbrook. 14. Tony Puletua & Jon Wilkin. 15. Willie Manu & Anthony Laffranchi. 16. Mark Flanagan & Paul Clough. 17. Gary Wheeler & Josh Jones. 18. Lee Gaskell & Thomas Makinson. 19. Carl Forster & Nathan Ashe. 20. Joe Greenwood & Alex Walmsley. 21. Adam Swift & Anthony Walker. 22. Jordan Hand & Danny Yates. 23. Mark Percival & Don Speakman. 24 James Tilley 26. Under 19s squad. 27. Average attendance. 28. Saints first team squad – appearances, stats and total apps. 30. Superleague tables since 1996 32. In & Out 33. Representative Honours 35. Superleague record against all clubs. 39. Season records. 40. Match records. Designed by Gareth Wright 41. Individual records. Email: [email protected] 42. Appearance club. Twitter: @gazzwright Name & Address of Ground LANGTREE PARK, McMANUS DRIVE, ST HELENS, MERSEYSIDE, WA9 3AL. Official Correspondence Address for Club Kirsty Rush - ST HELENS RUGBY FOOTBALL CLUB, LANGTREE PARK, McMANUS DRIVE, ST HELENS, MERSEYSIDE, WA9 3AL. Switchboard tel. no. 01744 455050 PRESS General Fax No 01744 455055 ARRANGEMENTS General e-mail address [email protected] 5 Website www.saintsrlfc.com PERSONNEL Press arrangements for the 2013 season are as per Chairman 2012 with some slight amendments. Eamonn McManus No member of the press will be allowed to enter the 01744 455051 stadium without a ticket and there will be no seasonal [email protected] press passes issued. -

Sport Gulf Times

CCRICKETRICKET | Page 4 BBADMINTONADMINTON | Page 5 Captains Sindhu continue war and Saina of words on advance in Ashes eve Hong Kong Thursday, November 23, 2017 GOLF Rabia I 5, 1439 AH Day urges Tiger GULF TIMES Woods to go easy on comeback SPORT Page 6 UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE TENNIS Djokovic, Thiem set Hazard, Willian to dazzle at Qatar shine as Chelsea ExxonMobil Open cruise into last 16 Conte’s side beat 10-man Qarabag 4-0, reach knockouts with game to spare AFP Baku, Azerbaijan helsea powered into the Champions League last 16 as Eden Hazard and Willian in- spired a 4-0 thrashing of 10- Cman Qarabag yesterday. Antonio Conte’s side reached the knockout stages with a game to spare thanks to infl uential displays from Hazard and Willian at the Olympic Stadium that knocked Azerbaijanis Qarabag out of the competition. Chelsea will go into their last Group C fi xture against Atletico Madrid, who were scheduled to take on Roma at the Wanda Metropolitano later yesterday, on 10 points and still in with a chance of fi nishing top. Novak Djokovic has won the title in Doha for two straight years — 2016 and 2017. Hazard scored Chelsea’s fi rst-half opener from the penalty spot after his By Sports Reporter The Serbian, whose last major tour- pass to Willian provoked a foul on the Doha nament appearance was at the Wim- Brazilian from Rashad Sadygov, who bledon where he was forced to retire in was sent off as incredulous Qarabag the quarter-fi nal match against Tomas players questioned both the awarding efending champion Novak Berdych, will be looking forward to as- of the penalty and the red card. -

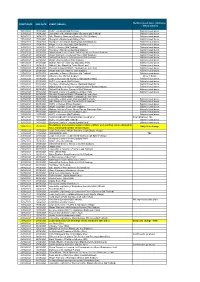

DATE END DATE EVENT (VENUE) Behind Closed Doors / Audience

Behind closed doors / Audience START DATE END DATE EVENT (VENUE) / Virtual (online) 15/04/2021 15/04/2021 MUFC v Granada (Old Trafford) Behind closed doors 15/04/2021 18/04/2021 Lancashire v Northamptonshire (Emirates Old Trafford) Behind closed doors 16/04/2021 16/04/2021 Sale Sharks v Gloucester Rugby (AJ Bell Stadium) Behind closed doors 17/04/2021 17/04/2021 Stockport v Maidenhead (Edgely Park) Behind closed doors 17/04/2021 17/04/2021 Rochdale v Accrington Stanley (Spotland Stadium) Behind closed doors 17/04/2021 17/04/2021 Wigan v Crewe Alexandra (DW Stadium) Behind closed doors 18/04/2021 18/04/2021 MUFC v Burnley (Old Trafford) Behind closed doors 20/04/2021 20/04/2021 Rochdale v Blackpool (Spotland Stadium) Behind closed doors 20/04/2021 20/04/2021 Bolton Wanderers v Carlisle Utd (University of Bolton Stadium) Behind closed doors 22/04/2021 22/04/2021 Wigan Warriors v Castleford Tigers (DW Stadium) Behind closed doors 23/04/2021 23/04/2021 Salford Red Devils v Centurions (AJ Bell Stadium) Behind closed doors 24/04/2021 24/04/2021 Wigan v Burton Albion (DW Stadium) Behind closed doors 24/04/2021 24/04/2021 Oldham Athletic v Grimsby (Boundary Park) Behind closed doors 24/04/2021 24/04/2021 Salford City v Mansfield Town (Moor Lane) Behind closed doors 29/04/2021 29/04/2021 Potential European Match - Champs Lge semi-final Behind closed doors 29/04/2021 29/04/2021 Wigan Warriors v Hull FC (DW Stadium) Behind closed doors 29/04/2021 02/05/2021 Lancashire v Sussex (Emirates Old Trafford) Behind closed doors 30/04/2021 30/04/2021 Billionaire -

The Football Tourist

The Football Tourist by Stuart Fuller www.ockleybooks.co.uk To the real CMF, twenty-years of great memories....some even featuring both of us. The Football Tourist Contents Page Number Introduction ix Foreword xiii The Cast xvii Chapter One: Welcome to Spakenburg 1 Chapter Two: Stockholm Syndrome 16 Chapter Three: A New Way of Life 26 Chapter Four: A Trip to Pleasure Island 41 Chapter Five: The Seven Deadly Sins 52 Chapter Six: French Resistance 62 Chapter Seven: A Scholar and a Gent 74 Chapter Eight: Bailing out the Euro Zone 86 Chapter Nine: Sex, Drugs and 80p Beer 99 Chapter Ten: On a (Swiss) Roll 112 Chapter Eleven: Red Hot and Chilly 123 Chapter Twelve: Roman Holiday 135 Chapter Thirteen: Slav to the Rhythm 147 The Football Tourist Introduction ix Chapter Fourteen: The Boys from Brazil 161 Chapter Fifteen: Yankee Doodle Dandy 177 Introduction Chapter Sixteen: Good Old Uncle Velbert 190 Chapter Seventeen: How Many Balloons Go By? 203 Chapter Eighteen: Push the Bloody Button! 214 Chapter Nineteen: Silent Night 231 Chapter Twenty: Dundee Derby Day Delight 243 Acknowledgements 256 Tourist: [too-r-ist] noun - A person who travels to and stays in places outside their usual environment for leisure, business and other purposes. x The Football Tourist Introduction xi Modern football is crap. How many times have I heard that full of heroes and villains. throwaway comment in recent years? There have even been Again, modern football is crap, right? a couple of books that eulogise about times gone by and how Again, rubbish. much better the beautiful game was when we only had three TV In searching for a title for this book, David Hartrick and I channels, sand for pitches and steak ‘n’ chips with light ale on threw a number of titles around before deciding on ‘The Football the side for a pre-match meal. -

List of European Stadiums by Capacity from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of European stadiums by capacity From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of European stadiums. They are ordered by their capacity; i.e. the maximum number of spectators the stadium can accommodate. The capacity figures are permanent total capacity, including seating and any standing areas, and excluding any temporary seating. Most large stadiums in Europe are used for association football, with the rest hosting rugby union, rugby league, cricket, track and field, bandy, and gaelic games such as Gaelic football, hurling and camogie. Camp Nou has the highest capacity in All stadiums with a capacity of 25,000 or more are included. The list Europe. includes all such stadiums in any country which is commonly accepted to be within the borders of Europe, including transcontinental countries that are partially in Europe (eg Turkey), or in a country commonly thought to be European for cultural or historic reasons (eg Armenia). Stadiums which are currently closed whilst undergoing extensive renovation, such as Silesian Stadium and Olimpiysky National Sports Complex, are not included in either the "current" or "under construction" sections. An asterisk indicates that a team does not play all of its home matches at that venue. Contents 1 Current stadiums 2 Under construction 3 See also 4 Notes and references Current stadiums Year of Capacity Stadium City Country Tenant Construction FC Barcelona, Catalonia Camp Nou 99,354[1] Barcelona Spain 1957 national football team. England national football team, Rugby League Challenge Cup Final Venue, FA Cup Final Venue, [2] England Wembley Stadium 90,000 London League Cup Final Venue, 2007 Football League play-off finals Venue, NFL International Series Venue.