Adventures of Peter Decoto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Practices and Carpenters' Tools That Created Alexandria's Kent Plantation House

Building Practices and Carpenters' Tools That Created Alexandria's Kent Plantation House By N. H. Sand and Peter Koch SouthernForest ExperimentStation Forest Service. U. S. Departmentof Agriculture I t is the year 1796or thereabouts. ily, and he succeeds so well that designed and made with good Louisiana is a Spanish colony with the dwelling still remains sound and materials. French traditions and culture. attractive after 175 years, a very Now known (from a later owner) Pierre Baillio II, of a prominent great age for a house in America. asthe Kent PlantationHouse, Bail- French family, has a sizeable grant To reach it takes good luck-escape lio's home has recently beenmade of land along the Red River near from fire, flood and the Civil War. into a museum in Alexandria, a a small town called EI Rapido. Continuous occupancy and the care short distance from where it was Baillio undertakes to have a that goes with it also helps. Most originally constructed. There it house built for himself and his fam- of all, the house must be soundly standsas testimony to the skins of early Louisiana carpenter crafts- men. In contrast to architects, who seemto leapinto print with no great difficulty, carpenters are a silent tribe. They come to the job with their tool chests, exercise many skins of construction and some of design, and then pass on. Often their works are their only record. Occasionally some tools survive and, after generationsof neglectand abuse,these may find their way int() antique shopsor museums. Thus it is difficult to speakin de- tail of the builders of any given house. -

Chapter 12 Review

FIGURE 12.1: “The Swan Range,” photograph by Donnie Sexton, no date 1883 1910 1869 1883 First transcontinental Northern Pacifi c Railroad completes Great Fire 1876 Copper boom transcontinental route railroad completed begins in Butte Battle of the 1889 1861–65 Little Bighorn 1908 Civil War Montana becomes a state Model T invented 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1862 1882 1862 Montana gold Montana Improvement Anton Holter opens fi rst 1875 rush begins Salish stop setting Company formed 1891 1905 commercial sawmill in Forest Reserve Act U.S. Forest Montana Territory fi res after confrontation 230 with law enforcement Service created READ TO FIND OUT: n How American Indians traditionally used fire n Who controlled Montana’s timber industry n What it was like to work as a lumberjack n When and why fire policy changed The Big Picture For thousands of years people have used forests to fill many different needs. Montana’s forestlands support our economy, our communities, our homes, and our lives. Forests have always been important to life in Montana. Have you ever sat under a tall pine tree, looked up at its branches sweeping the sky, and wondered what was happen- ing when that tree first sprouted? Some trees in Montana are 300 or 400 years old—the oldest living creatures in the state. They rooted before horses came to the Plains. Think of all that has happened within their life spans. Trees and forests are a big part of life in Montana. They support our economy, employ our people, build our homes, protect our rivers, provide habitat for wildlife, influence poli- tics, and give us beautiful places to play and be quiet. -

CLOSED SYLLABLES Short a 5-8 Short I 9-12 Mix: A, I 13 Short O 14-15 Mix: A, I, O 16-17 Short U 18-20 Short E 21-24 Y As a Vowel 25-26

DRILL BITS I INTRODUCTION Drill Bits Phonics-oriented word lists for teachers If you’re helping some- CAT and FAN, which they may one learn to read, you’re help- have memorized without ing them unlock the connection learning the sounds associated between the printed word and with the letters. the words we speak — the • Teach students that ex- “sound/symbol” connection. ceptions are also predictable, This book is a compila- and there are usually many ex- tion of lists of words which fol- amples of each kind of excep- low the predictable associa- tion. These are called special tions of letters, syllables and categories or special patterns. words to the sounds we use in speaking to each other. HOW THE LISTS ARE ORGANIZED This book does not at- tempt to be a reading program. Word lists are presented Recognizing words and pat- in the order they are taught in terns in sound/symbol associa- many structured, multisensory tions is just one part of read- language programs: ing, though a critical one. This Syllable type 1: Closed book is designed to be used as syllables — short vowel a reference so that you can: sounds (TIN, EX, SPLAT) • Meet individual needs Syllable type 2: Vowel- of students from a wide range consonant-e — long vowel of ages and backgrounds; VAT sounds (BAKE, DRIVE, SCRAPE) and TAX may be more appro- Syllable Type 3: Open priate examples of the short a syllables — long vowel sound sound for some students than (GO, TRI, CU) www.resourceroom.net BITS DRILL INTRODUCTION II Syllable Type 4: r-con- those which do not require the trolled syllables (HARD, PORCH, student to have picked up PERT) common patterns which have Syllable Type 5: conso- not been taught. -

Architectural and Design Uses of Reclaimed Wood Handout

A I B D Architectural and Design Uses of Reclaimed Wood Presenter: Welcome to Reclaimed Woods by Goodwin. George Goodwin is the original River Recovered specialist. For 36 years we’ve recovered logs from river bottoms. These were some of the first logs to be cut over 125 years ago from America’s virgin forest, so the wood is denser and has a richer patina. We offer a complete line of flooring, stair parts and millworks… solid or engineered… unfinished or pre-finished. George’s vision for Goodwin has always been to partner with the design build team. Our COO, Andrew, has 40+ years of manufacturing, install and finish expertise. Andrew works with architects and designers on specifications and builders and flooring professionals on technical expertise. Our Production Manager’s mechanical expertise controls the quality of your wood from proper kiln drying, to precision milling to grading by established standards. This attention to detail simplifies the installation to save you money. George locates salvaged wood to offer any grade you want. He rescues Wild Black Cherry, Mahogany after hurricanes and finds sustainably harvested exotics from community managed forests in Central America that are often forest certified. Who should attend? Building design professionals who specify reclaimed wood in residential or commercial applications. What benefits are gained by attending?: Learn the history of America’s first forests and evaluate variations in grades and know what to anticipate when specifying reclaimed and antique woods. Compare characteristics -

Education Resources and Opportunities

Coeur d’Alene’s Old Mission State Park Education Resources and Opportunities Coeur d’Alene’s Old Mission State Park Coeur d’Alene’s Old Mission State Park is home to Idaho’s oldest standing building, the Mission of the Sacred Heart or Cataldo Mission. The site has a long history associated with various groups, cultures, and religious beliefs. The main story told is the coming together of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe and Jesuit Missionaries. Together they built the Mission and a self-sustaining village with minimal tools and supplies. This story is unique to Idaho and an important part of the history of the Pacific Northwest. The site is sacred to many different people for many different reasons. The permanent exhibit Sacred Encounters: Father De Smet and the Indians of the Rocky Mountain West is housed within the park visitor center. This Smithsonian-quality exhibit includes video, displays, and artifacts from around the world. The history of the site is varied and a continuous story of life and historic events. Throughout its rich history, the mission has served many purposes: as a place of worship for Native people; a hospitality and supply station for settlers, miners and military personnel; a working farm; a disembarkation point for boats heading up the Coeur d’Alene River carrying miners and later railroad and pipeline workers; a Jesuit novitiate; a gathering place to sign treaties and resolve issues; and, the site of a labor dispute between union and non-union miners. Many colorful people, cultures and activities converged at this important spiritual, cultural and historic site. -

COVERED BRIDGES C. W. W. Elkin 1841 Charles Dickens Visited

COVERED BRIDGES C. W. W. Elkin 1841 Charles Dickens visited America and when he returned to England he had some varied experiences to record, often in Ina critical way, of places and things he had seen in the United States. One such experience Iwish to cite here. "We crossed the river by a wooden bridge, roofed and covered on all sides, and nearly a mile in length. It was profoundly dark, perplexed with great beams, crossing and recrossing it at every possible angle ;and through the broad chinks and crevices in the floor, the rapid river gleamed, far down below, like a legion of eyes. We had no lamps; and as the horses stumbled and floundered through this place, toward the distant speck of dying light, it seemed interminable. Ireally could not at first persuade myself as we rumbled heavily on, filling the bridge with hollow noises, but what Iwas in a painful dream; for Ihad often dreamed of toiling through such places, and as often argued, even at the time, 'This cannot be reality'." 1 The bridge in question was one over the Susquehanna River at Harrisburg. After more than a century we can view with different eyes what the covered bridge has meant in the development of our country, practically as well as sentimentally. Bridges are more than just useful structures. They are the familiar and romantic landmarks of our countryside. The first question that naturally arises when the individual sees a covered bridge is: Why was the wooden bridge covered with a roof? Simply, one can answer by asking another question: Why is a roof put on a barn or a house? Primarily, of course, a roof over a bridge preserved the wooden structure from rotting during the summer and from freezing its joints during the winter. -

C:\Users\Joseph\Documents\ACC Graphics\Web Page Files\490

Extracted from: Occupation of Socastee Bluff: Data Recovery at the Singleton Sawmill Site (38HR490), Horry County. Archaeological Consultants of the Carolinas, Inc., 2007. Chapter VI. The Sawmill at Enterprise Our third research question guiding this data recovery emphasized an Industrial Period (1880-1920) research theme. In Chapter II, we presented a general research theme to guide our investigation of the industrial sawmill complex at Enterprise: Industrial Period Research Themes (1880-1920). Preliminary historical research indicates that 38HR490 may have been abandoned by the 1880s. However, by 1910 it appears that the site is the center of activity associated the community of Enterprise. Spurred by a thriving lumber industry, a number of sawmills sprang up in the county. Initial research revealed that Mr. J. W. Singleton owned and operated a sawmill at Enterprise. The structural remains at this site identified along the river margin provide an opportunity to archaeologically investigate intact features associated with a sawmill. Furthermore, historical research should provide details about small privately owned sawmills in the area and shed light on this once-thriving lumber community. This portion of our research therefore falls under the auspices of Industrial Archaeology, a term first used 50 years ago to apply to the study of the physical remains of the Industrial Revolution in England (1750-1830) (Nevell 2007). Although initially referring to the archaeology of the physical remains of the Industrial Revolution, the term “industrial archaeology” has come to mean “the recording, study, interpretation and preservation of the physical remains of industrially related artifacts, sites and systems within their social and historical contexts” (Clouse 1995). -

Whipsaw All Right Ism, for Spokane First Coal Shipped Local and General

- •W Coal=j)roduction will maintain big payroll here. >.a 4 A- •• • f*| m. •:$ii Avoid extremes: 0h. the pathway of life choose the middle course Mining; is the leading industry of the Similkarri<|fi^rjd:is capable of vast development, not a tenth of1 it feeing, as yet, prospected—It is the Prospector's Paradise, easy of access and virtually unlimited in area—Manufacturing facilities are excellent—Healthy climate. Vol.X. No. 43. PRINCETON, B.C., WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 20, 1909. $2 a :Year in i&dvaticV WHIPSAW ALL RIGHT ISM, FOR SPOKANE FIRST COAL SHIPPED LOCAL AND GENERAL Camp Makes Good in High Princeton Output will Compete Two Carloads for Hedley Gold Buildings Projected and in Con Assays and Inviting in Market of the Big Mines Co. Fifjst Over struction in Various to CapiMi^l Inland Capital. V.,V,&E.Line. Parts Town. Wagon Road would Facilitate Devel Sunset Han Drops Into Spokane and V.F.M. Co. will be Ready to Supply leer not Down from Higher Altitudes opment—Ore May be Hauled Says Things to Reporter on Consumers Abroad—Spur not Portends Late and Moderate to Princeton. "^ra Live Subjects. yet Completed. Winter Season. Whipsaw has sprung into public notice The following interview in the.Spokes The first shipment of coal from the Remember the Thanksgiving dinner to purely on its merits and every week is man-Review is., another illustration of Vermilion Forks Co's mine is bfejrijj made be served by the Ladies' Aid Monday J. P. McConnell's deepMnterest in every prolific with solid, tangible results which now to the Hedley Gold Mines Co. -

Cataldo Mission

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Cataldo Mission AND/OR COMMON Coeur d'Alene Mission of the Sacred Heart LOCATION STREET & NUMBER U.S. Interstate 9Q (I mile west of Cataldo, Idaho) _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN 22 miles east of Coeur d'Alene CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT ___ VICINITY OF 1st. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Idaho 16 Kootenai 03S • QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE XXMUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE —BOTH XWORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT ^RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS -*YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO _ MILITARY _ OTHER: (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Administered by^ the Idaho State Parks and Recreation Department STREET& NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Boise VICINITY OF Idaho LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Kootenai County Courthouse REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC STREETS. NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Coeur d'Alene Idaho REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1963 .^FEDERAL _STATE COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X_EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XX\LTERED (minor) —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Father Anthony Ravalli, a Jesuit priest born in Ferrara, Italy was called upon to design the Coeur d'Alene Mission of the Sacred Heart. At the time, Father Ravalli was stationed at St. -

Two Beers Brewing-Seattle

Inland NW Craft Beer Festival September 20-21, 2019 Tickets Available Now Beer list as of 9/5/19 509 Bierwerks-Wenatchee 1) Brew Ha Ha IPA (ABV 6.2% / IBU 80) Our Brew Ha Ha IPA is a homage to a benchmark of the American IPA style. It’s brewed in a traditional Northwest style; American base malt and crystal malt create the big body and supporting grainy sweetness, while Jarrylo® and Mosaic® hops deliver pronounced tropical citrus aroma and flavor. In the glass you get a pale amber color, hop intensity and malt.Spicy stone fruit, tropical citrus and great malt backbone make this a well balanced IPA . 2) #14 Nut Brown (ABV 6.1% / IBU 32) Styled after southern English brown ales, our Nut Brown is a great all-around beer. It’s mild enough for light beer drinkers, but characterful enough for more experienced craft beer lovers. The finished product exhibits a deep copper color, fruit/caramel flavor and aroma with toasty, chocolatey notes and a hint of coffee. 3) 509 Fest Bier (ABV 6.0% / IBU 22) Moderately high malt flavor presenting soft sweetness basic to Pilsner malt with an added hint of light toast. Hop bitterness brings slight balancing to the malt, while flavor is spicy, and herbal. Clean lager character. 4) Local Local Fresh Hop IPA (ABV 5.9% / IBU 60) Our once a year fresh (wet) hop beer brewed within hours of being picked in Lake Chelan. Pacific Northwest Style Fresh Hop IPA made with glutinous amounts of fresh (wet) Chinook. Very full and complex spectrum of hop aromas and flavors including; citrusy, piney, and herbal. -

Elevating Design: Building Design As a Dynamic Capability

Elevating Design Building Design as a Dynamic Capability Ryan R. Rosensweig, bba A thesis submitted to the School of Design from the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning at the University of Cincinnati for the degree of Master of Design © 2011 Ryan R. Rosensweig committee Craig M. Vogel, mid (Chair) Associate Dean Professor—Industrial Design College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati M. Ann Welsh, phd Professor Emerita—Management College of Business University of Cincinnati Dale L. Murray, mdes Associate Professor—Industrial Design College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati abstract This thesis focuses on the interaction between design and business, exploring its impact on the success of organizations through two case studies of design managers, Dan Harden, Chief Executive Officer for Whipsaw Inc and Sam Lucente, Global Vice President of Design for Hewlett-Packard. Through an analysis of organizational strategy and design, this thesis proposes a theoretical model that identifies how design becomes a dynamic capability for any organization when its promotion and support shifts from a person to a function. Finally, based on this model, this thesis analyzes the effectiveness of design thinking in supporting design as a dynamic capability and offers conclusions for the elevation of a design function in support of a sustained competitive advantage in organizations. acknowledgements To my family, friends, faculty, and mentors—you are my inspiration. table of contents -

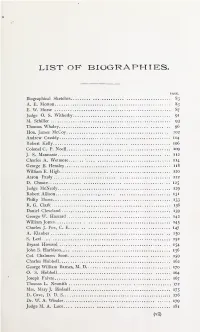

List Ok Biographies

list ok biographies Biographical Sketches 83 A. E. Morton 83 E. W. Morse 87 Judge O. S. Witherby 9 i M. Schiller 93 Thomas Whaley 96 Hon. James McCoy 102 Andrew Cassidy 104 Robert Kelly 106 Colonel C. P. Noell 109 1 12 J. S. Mannasse Charles A. Wetmore 114 George B. Plensley xi8 William E. High 120 Aaron Pauly 122 D. Choate 125 Judge McNealy 129 Robert Allison 131 Philip Morse 133 R. G. Clark 136 Daniel Cleveland 139 George W. Hazzard 142 William Jorres 145 Charles J. Fox, C. E 147 A. Klauber 150 S. Levi 152 Bryant Howard 154 John S. Harbison.., 156 Col. Chalmers Scott i.S9 Charles Hubbell 162 George William Barnes, M. D, 170 O. S. Hubbell 164 Joseph Faivre . 167 Thomas L. Nesmith 172 Mrs. Mary J. Birdsall 175 D. Cave, D. D. S 176 Dr. W. A. Winder 179 Judge M. A. Luce. ... ...... 181 . LIST OF BIOGRAPHIES. George A. Cowles 184 Dr. P. C. Remondino 187 N. M. Conklin 190 R. A. Thomas 192 Judge John D. Works 194 L. S. McClure 197 Governor Robert W. Waterman 199 Col. W. H. Holabird 203 Col. John A. Helphingstine. 206 Willard N. Fos 208 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES- A. E. HORTON. It was the boast of Augustus Caesar that he found Rome in brick and he should leave it in marble. With more regard to truth might Alonzo E. Horton, speaking in the figurative style adopted by the Roman Emperor, remark that he found San Diego a barren waste, and to-day, as he looks down from the portico of his beautiful mansion on Florence Heights, he sees it a busy, thriving city of 35,000 inhabitants.