A Howling Wilderness: Felling the Giants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impacts of Early Land-Use on Streams of the Santa Cruz Mountains: Implications for Coho Salmon Recovery

Impacts of early land-use on streams of the Santa Cruz Mountains: implications for coho salmon recovery San Lorenzo Valley Museum collection Talk Outline • Role of San Lorenzo River in coho salmon recovery • History of 19th century land-use practices • How these disturbances impacted (and still impact) ecosystem function and salmon habitat Central California Coast ESU Lost Coast – Navarro Pt. Coho salmon Diversity Strata Navarro Pt. – Gualala Pt. Coastal San Francisco Bay Santa Cruz Mountains Watersheds with historical records of Coho Salmon Dependent populations Tunitas Independent populations San Gregorio Pescadero Gazos Waddell Scott San Vicente Laguna Soquel San Lorenzo Aptos Land-use activities: 1800-1905 Logging: the early years • Pit and whipsaw era (pre-1842) – spatially limited, low demand – impacts relatively minor • Water-powered mills (1842-1875) – Demand fueled by Gold Rush – Mills cut ~5,000 board ft per day = 10 whip sawyers – Annual cut 1860 = ~10 million board ft • Steam-powered mills (1876-1905) – Circular saws doubled rate to ~10,000 board ft/day x 3-10 saws – Year-round operation (not dependent on water) – Annual cut 1884 = ~34 million board ft – Exhausted timber supply Oxen team skidding log on corduroy road (Mendocino Co. ca 1851) Krisweb.com Oxen team hauling lumber at Oil Creek Mill San Lorenzo Valley Museum collection oldoregonphotos.com San Vicente Lumber Company (ca 1908): steam donkey & rail line Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History Loma Prieta Mill, Mill Pond, and Rail Line (ca 1888) Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History The Saw-Dust Nuisance “We have always maintained that lumberman dumping their refuse timber and saw-dust into the San Lorenzo River and its tributaries were committing a nuisance. -

Mapping Ghost Towns in the Santa Cruz Mountains

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University GSP Projects Student and Alumni Works Fall 12-2020 Mapping Ghost Towns in the Santa Cruz Mountains Sarah Christine Brewer Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/gspproject Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Geographic Information Sciences Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Brewer, Sarah Christine, "Mapping Ghost Towns in the Santa Cruz Mountains" (2020). GSP Projects. 1. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/gspproject/1 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student and Alumni Works at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in GSP Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mapping Ghost Towns in the Santa Cruz Mountains GSP 510 Final Project BY: SARAH BREWER DECEMBER 2020 Abstract This project identifies areas of archaeological sensitivity for historic resources related to the segment of the South Pacific Coast Railroad that spanned from Los Gatos to Glenwood in the steep terrain of the Santa Cruz Mountains in Central California. The rail line was only in use for 60 years (1880-1940) until the completion of a major highway drew travelers to greater automobile use. During the construction and operation of the rail line, small towns sprouted at the railroad stops, most of which were abandoned along with the rail line in 1940. Some of these towns are now inundated by reservoirs. This project maps the abandoned rail line and “ghost towns” by using ArcGIS Pro (version 2.5.1) to digitize the railway, wagon roads, and structures shown on a georeferenced topographic quadrangle created in 1919 (Marshall et al., 1919). -

Building Practices and Carpenters' Tools That Created Alexandria's Kent Plantation House

Building Practices and Carpenters' Tools That Created Alexandria's Kent Plantation House By N. H. Sand and Peter Koch SouthernForest ExperimentStation Forest Service. U. S. Departmentof Agriculture I t is the year 1796or thereabouts. ily, and he succeeds so well that designed and made with good Louisiana is a Spanish colony with the dwelling still remains sound and materials. French traditions and culture. attractive after 175 years, a very Now known (from a later owner) Pierre Baillio II, of a prominent great age for a house in America. asthe Kent PlantationHouse, Bail- French family, has a sizeable grant To reach it takes good luck-escape lio's home has recently beenmade of land along the Red River near from fire, flood and the Civil War. into a museum in Alexandria, a a small town called EI Rapido. Continuous occupancy and the care short distance from where it was Baillio undertakes to have a that goes with it also helps. Most originally constructed. There it house built for himself and his fam- of all, the house must be soundly standsas testimony to the skins of early Louisiana carpenter crafts- men. In contrast to architects, who seemto leapinto print with no great difficulty, carpenters are a silent tribe. They come to the job with their tool chests, exercise many skins of construction and some of design, and then pass on. Often their works are their only record. Occasionally some tools survive and, after generationsof neglectand abuse,these may find their way int() antique shopsor museums. Thus it is difficult to speakin de- tail of the builders of any given house. -

Conifer Communities of the Santa Cruz Mountains and Interpretive

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ CALIFORNIA CONIFERS: CONIFER COMMUNITIES OF THE SANTA CRUZ MOUNTAINS AND INTERPRETIVE SIGNAGE FOR THE UCSC ARBORETUM AND BOTANIC GARDEN A senior internship project in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS in ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES by Erika Lougee December 2019 ADVISOR(S): Karen Holl, Environmental Studies; Brett Hall, UCSC Arboretum ABSTRACT: There are 52 species of conifers native to the state of California, 14 of which are endemic to the state, far more than any other state or region of its size. There are eight species of coniferous trees native to the Santa Cruz Mountains, but most people can only name a few. For my senior internship I made a set of ten interpretive signs to be installed in front of California native conifers at the UCSC Arboretum and wrote an associated paper describing the coniferous forests of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Signs were made using the Arboretum’s laser engraver and contain identification and collection information, habitat, associated species, where to see local stands, and a fun fact or two. While the physical signs remain a more accessible, kid-friendly format, the paper, which will be available on the Arboretum website, will be more scientific with more detailed information. The paper will summarize information on each of the eight conifers native to the Santa Cruz Mountains including localized range, ecology, associated species, and topics pertaining to the species in current literature. KEYWORDS: Santa Cruz, California native plants, plant communities, vegetation types, conifers, gymnosperms, environmental interpretation, UCSC Arboretum and Botanic Garden I claim the copyright to this document but give permission for the Environmental Studies department at UCSC to share it with the UCSC community. -

Chapter 12 Review

FIGURE 12.1: “The Swan Range,” photograph by Donnie Sexton, no date 1883 1910 1869 1883 First transcontinental Northern Pacifi c Railroad completes Great Fire 1876 Copper boom transcontinental route railroad completed begins in Butte Battle of the 1889 1861–65 Little Bighorn 1908 Civil War Montana becomes a state Model T invented 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1862 1882 1862 Montana gold Montana Improvement Anton Holter opens fi rst 1875 rush begins Salish stop setting Company formed 1891 1905 commercial sawmill in Forest Reserve Act U.S. Forest Montana Territory fi res after confrontation 230 with law enforcement Service created READ TO FIND OUT: n How American Indians traditionally used fire n Who controlled Montana’s timber industry n What it was like to work as a lumberjack n When and why fire policy changed The Big Picture For thousands of years people have used forests to fill many different needs. Montana’s forestlands support our economy, our communities, our homes, and our lives. Forests have always been important to life in Montana. Have you ever sat under a tall pine tree, looked up at its branches sweeping the sky, and wondered what was happen- ing when that tree first sprouted? Some trees in Montana are 300 or 400 years old—the oldest living creatures in the state. They rooted before horses came to the Plains. Think of all that has happened within their life spans. Trees and forests are a big part of life in Montana. They support our economy, employ our people, build our homes, protect our rivers, provide habitat for wildlife, influence poli- tics, and give us beautiful places to play and be quiet. -

Preliminary Isoseismal Map for the Santa Cruz (Loma Prieta), California, Earthquake of October 18,1989 UTC

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Preliminary isoseismal map for the Santa Cruz (Loma Prieta), California, earthquake of October 18,1989 UTC Open-File Report 90-18 by Carl W. Stover, B. Glen Reagor, Francis W. Baldwin, and Lindie R. Brewer National Earthquake Information Center U.S. Geological Survey Denver, Colorado This report has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial stan dards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Introduction The Santa Cruz (Loma Prieta) earthquake, occurred on October 18, 1989 UTC (October 17, 1989 PST). This major earthquake was felt over a contiguous land area of approximately 170,000 km2; this includes most of central California and a portion of western Nevada (fig. 1). The hypocen- ter parameters computed by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) are: Origin time: 00 04 15.2 UTC Location: 37.036°N., 121.883°W. Depth: 19km Magnitude: 6.6mb,7.1Ms. The University of California, Berkeley assigned the earthquake a local magnitude of 7.0ML. The earthquake caused at least 62 deaths, 3,757 injuries, and over $6 billion in property damage (Plafker and Galloway, 1989). The earthquake was the most damaging in the San Francisco Bay area since April 18,1906. A major arterial traffic link, the double-decked San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, was closed because a single fifty foot span of the upper deck collapsed onto the lower deck. In addition, the approaches to the bridge were damaged in Oakland and in San Francisco. Other se vere earthquake damage was mapped at San Francisco, Oakland, Los Gatos, Santa Cruz, Hollister, Watsonville, Moss Landing, and in the smaller communities in the Santa Cruz Mountains. -

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared by: CALFIRE, San Mateo — Santa Cruz Unit The Resource Conservation District for San Mateo County and Santa Cruz County Funding provided by a National Fire Plan grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the California Fire Safe Council. M A Y - 2 0 1 0 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................1 Purpose.................................................................................................................................2 Background & Collaboration...............................................................................................3 The Landscape .....................................................................................................................6 The Wildfire Problem ..........................................................................................................8 Fire History Map................................................................................................................10 Prioritizing Projects Across the Landscape .......................................................................11 Reducing Structural Ignitability.........................................................................................12 x Construction Methods............................................................................................13 x Education ...............................................................................................................15 -

Community Wildfire Protection Plan Prepared By

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared by: CALFIRE, San Mateo — Santa Cruz Unit The Resource Conservation District for San Mateo County and Santa Cruz County Funding provided by a National Fire Plan grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the California Fire Safe Council. APRIL - 2 0 1 8 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................ 3 Background & Collaboration ............................................................................................... 4 The Landscape .................................................................................................................... 7 The Wildfire Problem ........................................................................................................10 Fire History Map ............................................................................................................... 13 Prioritizing Projects Across the Landscape .......................................................................14 Reducing Structural Ignitability .........................................................................................16 • Construction Methods ........................................................................................... 17 • Education ............................................................................................................. -

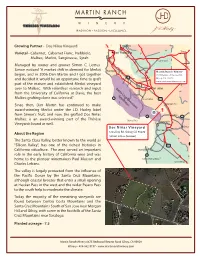

Dos Niñas Vineyard Berkeley

Growing Partner - Dos Niñas Vineyard Berkeley Tracy Varietal - Cabernet, Cabernet Franc, Nebbiolo, San Francisco Malbec, Merlot, Sangiovese, Syrah Livermore Managed by owner and grower Simon C. Lemus. Simon noticed "A market shift in demand for Merlot San Mateo Martin Ranch Winery began, and in 2006 Dan Martin and I got together 6675 Redwood Retreat Rd, and decided it would be an opportune time to graft 92 Gilroy, CA 95020 www.martinranchwinery.com part of the mature and established Merlot vineyard over to Malbec. With relentless research and input Santa Cruz Mountains San Jose from the University of California at Davis, the best Appellation Malbec grafting clone was selected." 1 Los Gatos 101 Since then, Dan Martin has continued to make Morgan Hill award-winning Merlot under the J.D. Hurley label from Simon's fruit, and now, the grafted Dos Niñas Gilroy 1 152 Malbec is an award-winning part of the Thérèse Santa Cruz Watsonville Vineyards brand as well. Dos Niñas Vineyard Hollister San Juan Bautista About the Region 1225 Day Rd, Gilroy, CA 95020 Simon Limas (Grower) The Santa Clara Valley, better known to the world as "Silicon Valley", has one of the richest histories in 101 California viticulture. The area served an important Monterey role in the early history of California wine and was 1 home to the pioneer winemakers Paul Masson and Carmel Valley Village Charles Lefranc. Greenfield The valley is largely protected from the inuence of the Pacic Ocean by the Santa Cruz Mountains, although coastal breezes that enter a small opening at Hecker Pass in the west and the wider Pajaro Pass to the south help to moderate the climate. -

Unit Strategic Fire Plan San Mateo

Unit Strategic Fire Plan San Mateo - Santa Cruz Cloverdale VMP - 2010 6/15/2011 Table of Contents SIGNATURE PAGE ................................................................................................................................ 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 3 SECTION I: UNIT OVERVIEW UNIT DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................................. 4 UNIT PREPAREDNESS AND FIREFIGHTING CAPABILITIES................................................. 8 SECTION II: COLLABORATION DEVELOPMENT TEAM ........................................................................................................... 12 SECTION III: VALUES AT RISK IDENTIFICATION OF ASSETS AT RISK ................................................................................ 15 COMMUNITIES AT RISK ........................................................................................................ 17 SECTION IV: PRE FIRE MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FIRE PREVENTION ................................................................................................................. 18 ENGINEERING & STRUCTURE IGNITABILITY ............................................................... 19 INFORMATION AND EDUCATION .................................................................................. 22 VEGETATION MANAGEMENT ............................................................................................. -

CLOSED SYLLABLES Short a 5-8 Short I 9-12 Mix: A, I 13 Short O 14-15 Mix: A, I, O 16-17 Short U 18-20 Short E 21-24 Y As a Vowel 25-26

DRILL BITS I INTRODUCTION Drill Bits Phonics-oriented word lists for teachers If you’re helping some- CAT and FAN, which they may one learn to read, you’re help- have memorized without ing them unlock the connection learning the sounds associated between the printed word and with the letters. the words we speak — the • Teach students that ex- “sound/symbol” connection. ceptions are also predictable, This book is a compila- and there are usually many ex- tion of lists of words which fol- amples of each kind of excep- low the predictable associa- tion. These are called special tions of letters, syllables and categories or special patterns. words to the sounds we use in speaking to each other. HOW THE LISTS ARE ORGANIZED This book does not at- tempt to be a reading program. Word lists are presented Recognizing words and pat- in the order they are taught in terns in sound/symbol associa- many structured, multisensory tions is just one part of read- language programs: ing, though a critical one. This Syllable type 1: Closed book is designed to be used as syllables — short vowel a reference so that you can: sounds (TIN, EX, SPLAT) • Meet individual needs Syllable type 2: Vowel- of students from a wide range consonant-e — long vowel of ages and backgrounds; VAT sounds (BAKE, DRIVE, SCRAPE) and TAX may be more appro- Syllable Type 3: Open priate examples of the short a syllables — long vowel sound sound for some students than (GO, TRI, CU) www.resourceroom.net BITS DRILL INTRODUCTION II Syllable Type 4: r-con- those which do not require the trolled syllables (HARD, PORCH, student to have picked up PERT) common patterns which have Syllable Type 5: conso- not been taught. -

Fire History in Coast Redwood Stands in San Mateo County Parks and Jasper Ridge, Santa Cruz Mountains1

Fire History in Coast Redwood Stands in San Mateo County Parks and Jasper Ridge, Santa Cruz Mountains1 Scott L. Stephens2 and Danny L. Fry3 Abstract Fire regimes in coast redwood forests in the northeastern Santa Cruz Mountains were determined by ring counts from 46 coast redwood stumps and live trees. The earliest recorded fire from two live samples was in 1615 and the last fire recorded was in 1884, although samples were not crossdated. For all sites combined, the mean fire return interval (FRI) was 12.0 years; the median FRI was 10 years. There was a significant difference in mean FRI between the four sampled sites. Past fire scars occurred most frequently in the latewood portion of the annual ring or during the dormant period. It is probable that the number of fires recorded in coast redwood trees is a subset of those fires that burned in adjacent grasslands and oak savannahs. The Ohlone and early immigrants were probably the primary source of ignitions in this region. Key words: fire return interval, seasonality Introduction Evidence of past fires is common in California’s coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens (D. Don) Endl.) forests. Redwood trees and stumps commonly exhibit fire scars in their annual growth rings, charred bark, and burned-out basal cavities. Recent research has documented the ecological role of fire in coast redwood forests (Brown and Baxter 2003; Brown and others 1999; Brown and Swetnam 1994; Finney and Martin 1989, 1992; Jacobs and others 1985; Stuart 1987). The objective of this study is to determine the fire history of four coast redwood stands in the northeastern Santa Cruz Mountains of California.