Dead Channel Surfing: the Commonalities Between Cyberpunk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negatief07.Pdf

EDITORIAL INHALT Wer hätte das noch vor einem Jahr gedacht, 48 Adversus als wir mit unserer ersten Ausgabe in den 50 20 Astrovamps ....in diesen Läden gibt es das NEGAtief wichtigsten Gothic-Clubs Deutschlands aus- 45 Harald Bosh lagen: Heute ist das NEGAtief aus der Szene 43 Das Ich Media Markt: Bochum, Duisburg, München, Nürn- nur schwer wegzudenken und jetzt mit der 26 Derma-Tek berg-Kleinreuth, Memmingen, Augsburg, Magde- siebten Ausgabe auch zum ersten Mal in den burg, Chemnitz, Groß Gaglow, Dresden-Nickern, 16 Funker Vogt wichtigsten Plattenläden erhältlich, die ihr Goslar, Dessau, Günthersdorf, Aschaffenburg, Her- hier dem Kasten entnehmen könnt. 42 Geist zogenrath, Weiterstadt, Limburg, Wiesbaden, Bad 32 Greifenkeil Dürrheim, Karlsruhe, Pforzheim, Stuttgart, Hil- Neu in der aktuellen Ausgabe ist auch der 24 Grendel desheim, Oldenburg, Heide, Koblenz, Trier, Braun- alternative Wendetitel. Inspiriert von dem 13 In Mitra Medusa Inri schweig, Dresden-Mickten, Flensburg, Porta West- französischen Magazin Elegy haben wir uns 36 Jesus on Ecstasy falica, Kaiserslautern, Reutlingen, Sindelfi ngen, zu diesem zusätzlichen, rückwärtigen Ti- 22 Ladytron Viernheim, Karlsruhe, Saarbrücken, Heilbronn, telbild entschieden, um noch einer zweiten Potsdam, Greifswald, Stralsund, Neubrandenburg, Band den verdienten Titelplatz einräumen 6 Letzte Instanz Rostock-Brinkmannsdorf/Sievershagen, Berlin: zu können. Wir hoffen, dass Euch unser Ti- 21 Mechanical Moth Schönefeld, Biesdorf, Spandau, Hohenschönhausen, telgespann, bestehend aus Letzte Instanz 18 The Mission Steglitz, Neukölln, Wedding, Schöneweide und Funker Vogt begeistert. Die mittlerwei- 51 Pecadores le regelmäßige Web EP möchten wir ab jetzt 21 Das Präparat Saturn: Weimar, Dortmund, Gelsenkirchen, Müns- durch einen kleinen Unkostenbeitrag hono- ter, Kleve, Moers, Hamm, Hagen, Essen, Krefeld, rieren, der direkt den Bands zugute kommt 34 Purwien 14 Scream Silence Oberhausen, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Mainz, Köln- und dem generellen Trend, Musik umsonst Hürth, Neuss, Köln-Porz, Leverkusen, München zu erhalten, gegensteuert. -

June 2018 New Releases

June 2018 New Releases what’s PAGE inside featured exclusives 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 76 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 15 FEATURED RELEASES HANK WILLIAMS - CLANNAD - TURAS 1980: PIG - THE LONESOME SOUND 2LP GATEFOLD RISEN Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 50 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 52 Order Form 84 Deletions and Price Changes 82 PORTLANDIA: CHINA SALESMAN THE COMPLETE SARTANA 800.888.0486 SEASON 8 [LIMITED EDITION 5-DISC BLU-RAY] 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 HANK WILLIAMS - SON HOUSE - FALL - LEVITATE: www.MVDb2b.com THE LONESOME SOUND LIVE AT OBERLIN COLLEGE, LIMITED EDITION TRIPLE VINYL APRIL 15, 1965 A Van Damme good month! MVD knuckles down in June with the Action classic film LIONHEART, starring Jean-Claude Van Damme. This combo DVD/Blu-ray gets its well-deserved deluxe treatment from our MVD REWIND COLLECTION. This 1991 film is polished with high-def transfers, behind-the- scenes footage, a mini-poster, interviews, commentaries and more. Coupled with the February deluxe combo pack of Van Damme’s BLACK EAGLE, why, it’s an action-packed double shot! Let Van Damme knock you out all over again! Also from MVD REWIND this month is the ABOMINABLE combo DVD/Blu-ray pack. A fully-loaded deluxe edition that puts Bigfoot right in your living room! PORTLANDIA, the IFC Network sketch comedy starring Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein is Ore-Gone with its final season, PORTLANDIA: SEASON 8. The irreverent jab at the hip and eccentric culture of Portland, Oregon has appropriately ended with Season 8, a number that has no beginning and no end. -

Book-14 Web-Lmsx.Pdf

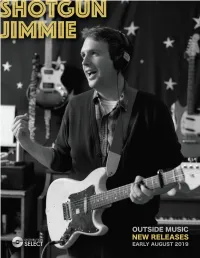

SHOTGUN JIMMIE – TRANSISTOR SISTER 2 LABEL: YOU’VE CHANGED RECORDS CATALOG: YC-039 FORMAT: LP/CD RELEASE DATE: AUGUST 2, 2019 Are you ready for the new sincerity?! Shotgun Jimmie’s new album Transistor Sister 2 is full of genuine pop gems that champion truth and love. Jimmie is joined by long- time collaborators Ryan Peters (Ladyhawk) and Jason Baird (DoMakeSayThink) for this sequel to the Polaris Prize nominated album Transistor Sister from 2011. José Contreras (By Divine Right) produced and recorded the record in Toronto, Ontario at The Chat Chateaux and joins the band on keys. In characteristic Shotgun Jimmie fashion, the songs on Transistor Sister 2 focus largely on family and friends with a heavy dose of nostalgia. Jimmie’s hyperbolic takes on the everyday reconstruct familiar scenarios, from traffic on the 401 (the beloved and scorned mega- highway through Toronto known to all touring musicians Blues Riffs as the place where punctual arrival at soundcheck goes Tumbleweed to die) to cooking dinner. Hot Pots Ablutions The album’s lead single Cool All the Time is a plea for Fountain people to abandon ego and strive for authenticity, Suddenly Submarine featuring contributions by Chad VanGaalen, Steven Piano (with band) Lambke and Cole Woods. The New Sincerity serves as The New Sincerity the album’s manifesto; it renounces cynicism and Cool All The Time promotes positivity. Sappy Slogans Highway 401 Jack Pine Sorry We’re Closed Shotgun Jimmie: IG: @shotgunjimmie FB: @shotgunjimmie Twitter: @jimmieshotgun You’ve Changed Records: www.youvechangedrecords.com CD – CD-YC-039 LP with download – LP-YC-039 Twitter: @youvechangedrec IG: @youvechangedrecords FB: @youvechangedrecords Also available from You’ve Changed Records: Partner – Saturday The 14th (YC-038) 12”EP/CD You’ve Changed Records Steven Lambke – Dark Blue (YC-037) LP 123 Pauline Ave. -

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES: STAHLPLANET – Leviamaag Boxset || CD-R + DVD BOX // 14,90 € DMB001 | Origin: Germany | Time: 71:32 | Release: 2008 Dark and weird One-man-project from Thüringen. Ambient sounds from the world Leviamaag. Black box including: CD-R (74min) in metal-package, DVD incl. two clips, a hand-made booklet on transparent paper, poster, sticker and a button. Limited to 98 units! STURMKIND – W.i.i.L. || CD-R // 9,90 € DMB002 | Origin: Germany | Time: 44:40 | Release: 2009 W.i.i.L. is the shortcut for "Wilkommen im inneren Lichterland". CD-R in fantastic handmade gatefold cover. This version is limited to 98 copies. Re-release of the fifth album appeared in 2003. Originally published in a portfolio in an edition of 42 copies. In contrast to the previous work with BNV this album is calmer and more guitar-heavy. In comparing like with "Die Erinnerung wird lebendig begraben". Almost hypnotic Dark Folk / Neofolk. KNŒD – Mère Ravine Entelecheion || CD // 8,90 € DMB003 | Origin: Germany | Time: 74:00 | Release: 2009 A release of utmost polarity: Sudden extreme changes of sound and volume (and thus, in mood) meet pensive sonic mindscapes. The sounds of strings, reeds and membranes meet the harshness and/or ambience of electronic sounds. Music as harsh as pensive, as narrative as disrupt. If music is a vehicle for creating one's own world, here's a very versatile one! Ambient, Noise, Experimental, Chill Out. CATHAIN – Demo 2003 || CD-R // 3,90 € DMB004 | Origin: Germany | Time: 21:33 | Release: 2008 Since 2001 CATHAIN are visiting medieval markets, live roleplaying events, roleplaying conventions, historic events and private celebrations, spreading their “Enchanting Fantasy-Folk from worlds far away”. -

Post-Human Nightmares

Post-Human Nightmares Mark Player 13 May 2011 A man wakes up one morning to find himself slowly transforming into a living hybrid of meat and scrap metal; he dreams of being sodomised by a woman with a snakelike, strap-on phallus. Clandestine experiments of sensory depravation and mental torture unleash psychic powers in test subjects, prompting them to explode into showers of black pus or tear the flesh off each other's bodies in a sexual frenzy. Meanwhile, a hysterical cyborg sex-slave runs amok through busy streets whilst electrically charged demi-gods battle for supremacy on the rooftops above. This is cyberpunk, Japanese style : a brief filmmaking movement that erupted from the Japanese underground to garner international attention in the late 1980s. The world of live-action Japanese cyberpunk is a twisted and strange one indeed; a far cry from the established notions of computer hackers, ubiquitous technologies and domineering conglomerates as found in the pages of William Gibson's Neuromancer (1984) - a pivotal cyberpunk text during the sub-genre's formation and recognition in the early eighties. From a cinematic standpoint, it perhaps owes more to the industrial gothic of David Lynch's Eraserhead (1976) and the psycho-sexual body horror of early David Cronenberg than the rain- soaked metropolis of Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982), although Scott's neon infused tech-noir has been a major aesthetic touchstone for cyberpunk manga and anime institutions such as Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira (1982- 90) and Masamune Shirow's Ghost in the Shell (1989- ). In the Western world, cyberpunk was born out of the new wave science fiction literature of the sixties and seventies; authors such Harlan Ellison, J.G. -

The Virtual Worlds of Japanese Cyberpunk

arts Article New Spaces for Old Motifs? The Virtual Worlds of Japanese Cyberpunk Denis Taillandier College of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto 603-8577, Japan; aelfi[email protected] Received: 3 July 2018; Accepted: 2 October 2018; Published: 5 October 2018 Abstract: North-American cyberpunk’s recurrent use of high-tech Japan as “the default setting for the future,” has generated a Japonism reframed in technological terms. While the renewed representations of techno-Orientalism have received scholarly attention, little has been said about literary Japanese science fiction. This paper attempts to discuss the transnational construction of Japanese cyberpunk through Masaki Goro’s¯ Venus City (V¯ınasu Shiti, 1992) and Tobi Hirotaka’s Angels of the Forsaken Garden series (Haien no tenshi, 2002–). Elaborating on Tatsumi’s concept of synchronicity, it focuses on the intertextual dynamics that underlie the shaping of those texts to shed light on Japanese cyberpunk’s (dis)connections to techno-Orientalism as well as on the relationships between literary works, virtual worlds and reality. Keywords: Japanese science fiction; cyberpunk; techno-Orientalism; Masaki Goro;¯ Tobi Hirotaka; virtual worlds; intertextuality 1. Introduction: Cyberpunk and Techno-Orientalism While the inversion is not a very original one, looking into Japanese cyberpunk in a transnational context first calls for a brief dive into cyberpunk Japan. Anglo-American pioneers of the genre, quite evidently William Gibson, but also Pat Cadigan or Bruce Sterling, have extensively used high-tech, hyper-consumerist Japan as a motif or a setting for their works, so that Japan became in the mid 1980s the very exemplification of the future, or to borrow Gibson’s (2001, p. -

Download the PDF Here

From the Mail Art network, We—’We’ being Jaye and me as one physical being, just to VESTED clarify*—We, as Genesis in those days, heard from an artist called Anna Banana. One day she wrote to me and we asked her about this mythical INTEREST fi gure we’d heard about called Monte Cazazza. She wrote back and said, ‘Monte Cazazza is a Genesis Breyer P-Orridge in conversation sick, dangerous, sociopathic individual. Why, with Mark Beasley once, Monte came to an art opening dressed like a woman in his long coat, carrying a briefcase and waving a Magnum revolver. In the briefcase was a dead cat and he locked the doors, held everybody in the art opening at gunpoint, took the cat out, poured lighter fl uid on it and set it on fi re. Oh, and the stench fi lled the room. He just started to laugh and then he left again. You don’t want to know this person!’ Wrong. (laughs) We did wantwant to know this person. Of course, once we heard how awful he was, we decided to correspond with Monte. We used to send each other the most grotesque and unpleasant things we could think of. One time, we sent him a big padded envelope and inside it were a pint of maggots and chicken legs and offal from the butcher, mixed up with pornography and so on. By the time it got to California to his P.O. Box, it stank! He was temporarily restrained by the security at the post offi ce. -

December 2020 New Releases

December 2020 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 59 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 12 FEATURED RELEASES Video WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. THE DAVE BRUBECK THE RESIDENTS - 35 FEATURING MICK ROSSI - QUARTET - IN BETWEEN DREAMS: Film LIVE IN TOKYO TIME OUTTAKES LIVE IN SAN FRANCISCO Films & Docs 36 Faith & Family 56 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 57 Order Form 69 Deletions & Price Changes 65 TREMORS MANIAC A NIGHT IN CASABLANCA 800.888.0486 (2-DISC SPECIAL EDITION) 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. BERT JANSCH - SUPERSUCKERS - FEATURING MICK ROSSI - BEST OF LIVE MOTHER FUCKERS BE TRIPPIN’ TIME OUT AND TAKE FIVE! LIVE IN TOKYO We could use a breather from what has been a most turbulent year, and with our December releases, we provide a respite with fantastic discoveries in the annals of cool jazz. THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET “TIME OUTTAKES” is an alternate version of the masterful TIME OUT 1959 LP, with the seven tracks heard for the first time in crisp, different versions with a bonus track and studio banter. The album’s “Take Five” is the biggest selling jazz single ever, and hearing this in different form is downright thrilling. On LP and CD. Also smooth jazz reigns supreme with a CD release of a newly discovered live performance from sax legend GEORGE COLEMAN. “IN BALTIMORE” is culled from a 1971 performance with detailed liner notes and rare photos. Kick Out the Jazz! Something else we could use is a release from oddball novelty song collector DR. -

Sept. 7-13, 2017

SEPT. 7-13, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE • WWW.WHATZUP.COM • FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE GET THE GEAR YOU WANT TODAY! 48MONTHS 0% INTEREST*** ON 140+ TOP BRANDS | SOME RESTRICTIONS APPLY 36MONTHS 0% INTEREST** ON 100+ TOP BRANDS | SOME RESTRICTIONS APPLY WHEN YOU USE THE SWEETWATER CARD. 36/48 EQUAL MONTHLY PAYMENTS REQUIRED. SEE STORE FOR DETAILS. NOW THROUGH OCTOBER 2 5501 US Hwy 30 W • Fort Wayne, IN Music Store Hours: Mon–Thurs 9–9 • Fri 9–8 Sat 9–7 • Sun 11–5 2 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- www.whatzup.com ---------------------------------------------------------- September 7, 2017 whatzup Volume 22, Number 6 e’re calling this our Big Fat Middle Waves issue since our cover features the MAIN STAGE: festival, now in its second year, and we’ve got a 16-page guide to all things • A Dancer’s Legacy – SEP 22 & 23 Middle Waves inside. Check out Steve Penhollow’s feature story on page 4, • The Nutcracker – DEC 1 thru 10 Wread the guide cover to cover and on the weekend of Sept. 15-16 keep whatzup.com pulled up on your mobile phone’s web browser. We’ll be posting Middle Waves updates • Coppélia – MAR 23-25 all day long so you’ll always know what’s happening where. • Academy Showcase – MAY 24 If you’ve checked out whatzup.com lately, you’ve probably noticed the news feed. It’s FAMILY SERIES: the home page on mobile phones and one of the four tabs on the PC version, and it THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 28 allows our whatzup advertisers to talk directly to whatzup.com users. If you’re one of • Frank E. -

April 2021 New Releases

April 2021 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s featured exclusives inside PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 79 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 11 ROY ORBISON - HEMINGWAY, A FILM BY JON ANDERSON - FEATURED RELEASES Video THE CAT CALLED DOMINO KEN BURNSAND LYNN OLIAS OF SUNHILLOW: 48 NOVICK. ORIGINAL 2 DISC EXPANDED & Film MUSIC FROM THE PBS REMASTERED DOCUMENTARY Films & Docs 50 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 78 Order Form 81 Deletions & Price Changes 84 THE FINAL COUNTDOWN DONNIE DARKO (UHD) ACTION U.S.A. 800.888.0486 (3-DISC LIMITED 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 EDITION/4K UHD+BLU- www.MVDb2b.com RAY+CD) WO FAT - KIM WILSON - SLY & ROBBIE - PSYCHEDELONAUT TAKE ME BACK RED HILLS ROAD DONNIE DARKO SEES THE LIGHT! The 2001 thriller DONNIE DARKO gets the UHD/4K treatment this month from Arrow Video, a 2-disc presentation that shines a crisp light on this star-studded film. Counting PATRICK SWAYZE and DREW BARRYMORE among its luminous cast, this first time on UHD DONNIE DARKO features the film and enough extras to keep you in the Darko for a long time! A lighter shade of dark is offered in the limited-edition steelbook of ELVIRA: MISTRESS OF THE DARK, a horror/comedy starring the horror hostess. Brand new artwork and an eye-popping Hi-Def presentation. Blue Underground rises again in the 4K department, with a Bluray/UHD/CD special of THE FINAL COUNTDOWN. The U.S.S. Nimitz is hurled back into time and can prevent the attack on Pearl Harbor! With this new UHD version, the KIRK DOUGLAS-led crew can see the enemy with crystal clarity! You will not believe your eyes when you witness the Animal Kingdom unleashed with two ‘Jaws with Claws’ horror movies from Severin Films, GRIZZLY and DAY OF THE ANIMALS. -

Cover Rather Than As Inert and Foreign Devices Ensoniq Clinic Dates

" . [figF-I-‘-ti; _| "| " '4 | T | -| ile- The independent New Magazine for Ensonlq User! Personullzlng Your KT-76 or KT-B8 Robby Herman I-‘ersonalixing Your KT-To or KT-B8 Robby Berrrtan .................................... cover rather than as inert and foreign devices Ensoniq Clinic Dates ................................. 3 of metal, plastic and silicon. Have you ‘Wavetable Wrangling on the SQ,il{S,+'KTs Jefilettan .................................................. 5 tailored your KT-To or KT-88 to your way of doing things yet? While we don't TS-lfli12 CD-ROM Compatibility — Part H Anthony Ferrara ........................................ 6 get to change the display colors, there Lightshieltl for Ensoniq Keyboards are a host of other useful options En- Mike Knit ................................................... ‘I soniq offers to make your KT feel like TS Hackerpatch ‘Winner home. Let’s discuss them. Sam Mime ................................................ .. DP Stuff — Either Reverbs Just so we‘re all experiencing the same Ray Legniai .............................................. ID thing, press the Select Sound button. Loop Modulation for the EPSIASR You may have to press Bank a few times Jack Schiejfer .......................................... 13 until there’s a dinky “r” in the upper Sampler Hackerpatch: Industrial Bass left-hand comer of the display. Now Tarn Shear . ............................................... 14 Yesterday I got a new waveform editor press the button above the 0 and then the Optimizing Your Synthesizer Palette for my Mac. It’s a beautifully fu.nction- button below the 4 to select ROM Sound Pat Fin.-e:'gan ............................................ 15 ing program -- great new features and D4, Big Money Pad. (You want to make SQIKSIKT Sounds: Trumpets no crashes so far. Thumbs up. And like big money, don’t you? Sure, we all do.). -

DEAD CHANNEL SURFING: Cyberpunk and Industrial Music

DEAD CHANNEL SURFING: Cyberpunk and industrial music In the early 1980s from out of Vancouver, home of cyberpunk writer William Gibson and science fiction film-maker David Cronenberg, came a series of pioneering bands with a similar style and outlook. The popular synth-pop band Images in Vogue, after touring with Duran Duran and Roxy Music, split into several influential factions. Don Gordon went on to found Numb, Kevin Crompton to found Skinny Puppy, and Ric Arboit to form Nettwerk Records, which would later release Skinny Puppy, Severed Heads, Moev, Delerium and more. Controversial band Numb ended up receiving less attention than the seminal Skinny Puppy. Kevin Crompton (now called Cevin Key) joined forces with Kevin Ogilvie (Nivek Ogre) and began their career by playing in art galleries. After their friend Bill Leeb quit citing ‘creative freedom’ disputes, they embarked on a new style along with the help of newly recruited Dwayne Goettel. Leeb would go on to found Front Line Assembly with Rhys Fulber in 1986. The style of music created by these bands, as well as many similar others, has since been dubbed ‘cyberpunk’ by some journalists. Cyberpunk represents an interesting coupling of concepts. It can be dissected, as Istvan Csiscery-Ronay has shown, into its two distinct parts, ‘cyber’ and ‘punk’. Cyber refers to cybernet- ics, the study of information and control in man and machine, which was created by U.S. American mathematician Norbert Wiener fifty years ago. Wiener fabricated the word from the Greek kyber- netes, meaning ‘governor’, ‘steersman’ or ‘pilot’ (Leary, 1994: 66). The second concept, punk, in the sense commonly used since 1976, is a style of music incorporating do-it-yourself (d.i.y) techniques, centred on independence and touting anarchist attitudes.