Memory and Film in Post-Dictatorial Spain" (2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

Flamenco Flamenco

FLAMENCO FLAMENCO 01. SYNOPSIS 02. DIRECTOR’S NOTES 03. CARLOS SAURA 04. VITTORIO STORARO 05. CAST & CREW 06. FILM DETAILS 07. THE PRODUCTION COMPANY 01. SYNOPSIS Considered the greatest exponent of the particular way of making musical films of Carlos Saura, Flamenco, flamenco arises, through a journey of light and life, the evolution of the songs, dances and music of this art that, in the director own words, would be heritage of the universe. With the experience and knowledge that Carlos Saura’s films have gained over time, we enter in the roads of the existing talents of this art so alive and dynamic that flamenco is it, to present his new film which uses innovative elements, in the technical field as in the narrative, becoming a unique production. The film shows that there is a powerful new flamenco, of young talents finding their way in our country and beyond our borders, but the reality of this art can not be reflected in the right way without some of the great living masters that we are fortunate to have in Spain. 02. DIRECTOR’S NOTES Carlos Saura It is always difficult to write about the ideas that lead me to create my musical films. It is difficult because the actual scripts I use are barely three or four pages long, where the different dances that have been chosen are in order, with the artist’s name and the space in which the dance might develop. It is even more difficult because part of the stimulus, the fun that always comes with the filming is based – let's face it – on the possibility of improvising in this type of cinema. -

Guillermo Del Toro’S Bleak House

GuillermoAt Home With Monstersdel Toro By James Balestrieri Guillermo del Toro’s Bleak House. Photo ©Josh White/ JWPictures.com. LOS ANGELES, CALIF. — The essence of “Guillermo del Toro: At Home With Monsters,” the strange and wonderful exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) through November 27, is this: Guillermo del Toro, born in 1964, is a major writer and director whose films include Cronos (1993), The Devil’s Backbone (2001), Hellboy (2004), Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), Pacific Rim (2013) and Crimson Peak (2015). He is a master who creates worlds that embrace horror, science fiction, fantasy and fairy tales. He insists that, as fantastic as they are, these worlds are located and grounded beside, beneath and in the real world, our world — a world, he might argue, that we merely imagine as real. The membrane separating these worlds is thin, porous and portal-ridden. The worlds are distorted reflections of one another. This distortion becomes the occasion for his ideas and art. Page from Notebook 2 by Guillermo del Toro. Leather-bound notebook, ink on paper, 8 by 10 by 1½ inches. Collection of Guillermo del Toro. ©Guillermo del Toro. Photo courtesy Insight Editions. Jointly organized by LACMA with the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the Art Gallery of Ontario, this first retrospective of the filmmaker’s work arrays sculpture, paintings, prints, photography, costumes, ancient artifacts, books, maquettes and film to create a complex portrait of a creative genius. Roughly 60 of the 500 objects on view are from LACMA’s collection. More belong to the artist. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Plan My Spanish Film Festival 2014

Spanish Programme 2014 V10_Layout 1 24/03/14 6:18 PM Page 2 CONTENTS Contenido WELCOME - Rafael Bonachela...............................................................................................................................P3 FESTIVAL SPECIAL GUEST - Álex González..............................................................................................P4 OPENING NIGHT FILM..............................P5 CLOSING NIGHT FILM..............................P6 Living is Easy with Eyes Closed Witching & Bitching REEL COLABORACIÓN.....................P23 MELBOURNE SCHEDULE...............P41 FILMS International co-productions Ticketing & Events REEL ESPAÑOL..........................................P8 7th Floor........................................................P23 SYDNEY SCHEDULE.........................P44 Films from Spain Cannibal........................................................P24 Ticketing & Events Alpha....................................................................P8 I Thought it Was A Party...........P25 BRISBANE SCHEDULE.....................P48 Ticketing & Events Barcelona Inevitable....................................................P26 Summer Night..........................................P9 ADELAIDE SCHEDULE......................P52 The Golden Cage...............................P27 Combustion..............................................P10 Ticketing & Events The Longest Distance.................P28 Family United............................................P11 CANBERRA SCHEDULE...................P54 Ticketing -

CALENDAR January 23

BOWDOIN COLLEGE / ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND Cinema Studies CINE 2116 / SPAN 3116: Spanish Cinema: Taboo and Tradition Spring 2019 / MW 10:05 Elena Cueto Asín. Sills Hall 210 – 725‐3312 – email: [email protected] Office hours: Monday 2:45‐4, or by appointment. This course introduces students to film produced in Spain, from the silent era to the present, focusing on the ways in which cinema can be a vehicle for promoting social and cultural values, as well as for exposing social, religious, sexual, or historical taboos in the form of counterculture, protest, or as a means for society to process change or cope with issues from the past. Looks at the role of film genre, authorship, and narrative in creating languages for perpetuating or contesting tradition, and how these apply to the specific Spanish context. GRADE Class Participation 40% Essays 60% MATERIALS Film available on reserve at the LMC or/and on‐line. Readings on‐line and posted on blackboard CALENDAR January 23. Introduction January 28 ¡Átame! - Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (Pedro Almodóvar 1989) Harmony Wu “The Perverse Pleasures of Almodovar’s Átame” Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 5 (3) 2004: 261-271. Reviews and controversy: New York Times: February 11, April 22 and 23, June 24, May 4, May 24, July 20 of 1989 January 30 Silent Cinema: The Unconventional and the Conventional El perro andaluz- Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel 1927) Jordan Cox “Suffering as a Form of Pleasure: An Exploration of Black Humor in Un Chien Andalou” Film Matters 5(3) 2014: 14-18 February 4 and 6 La aldea maldita- The Cursed Village (Florian Rey 1929) Tatjana Pavlović 100 years of Spanish cinema [electronic resource] Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009: 15-20 Sánchez Vidal, Agustin. -

Memory, History, and Entrapment in the Temporal Gateway Film

Lives in Limbo: Memory, History, and Entrapment in the Temporal Gateway Film Sarah Casey Benyahia A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Department of Literature, Film, and Theatre Studies University of Essex October 2018 Abstract This thesis examines the ways in which contemporary cinema from a range of different countries, incorporating a variety of styles and genres, explores the relationship to the past of people living in the present who are affected by traumatic national histories. These films, which I’ve grouped under the term ‘temporal gateway’, focus on the ways in which characters’ experiences of temporality are fragmented, and cause and effect relationships are loosened as a result of their situations. Rather than a recreation of historical events, these films are concerned with questions of how to remember the past without being defined and trapped by it: often exploring past events at a remove through techniques of flashback and mise-en-abyme. This thesis argues that a fuller understanding of how relationships to the past are represented in what have traditionally been seen as different ‘national’ cinemas is enabled by the hybridity and indeterminacy of the temporal gateway films, which don’t fit neatly into existing categories discussed and defined in memory studies. This thesis employs an interdisciplinary approach in order to draw out the features of the temporal gateway film, demonstrating how the central protagonist, the character whose life is in limbo, personifies the experience of living through the past in the present. This experience relates to the specifics of a post-trauma society but also to a wider encounter with disrupted temporality as a feature of contemporary life. -

Avance Largometrajes 2014Feature Films Preview

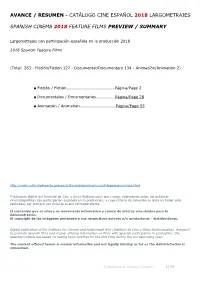

AVANCE / RESUMEN - CATÁLOGO CINE ESPAÑOL 2018 LARGOMETRAJES SPANISH CINEMA 2018 FEATURE FILMS PREVIEW / SUMMARY Largometrajes con participación española en la producción 2018 2018 Spanish Feature Films (Total: 263 - Ficción/Fiction 127 - Documental/Documentary 134 - Animación/Animation 2) ■ Ficción / Fiction…………………………………………Página/Page 2 ■ Documentales / Documentaries……………...Página/Page 28 ■ Animación / Animation……………………………..Página/Page 55 http://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/cultura/areas/cine/mc/catalogodecine/inicio.html Publicación digital del Instituto de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales que recoge información sobre las películas cinematográficas con participación española en la producción, y cuyo criterio de selección se basa en haber sido calificadas por primera vez durante el año correspondiente. El contenido que se ofrece es meramente informativo y carece de efectos vinculantes para la Administración. El copyright de las imágenes pertenece a sus respectivos autores y/o productoras - distribuidoras. Digital publication of the Institute for Cinema and Audiovisual Arts (Instituto de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales), designed to promote Spanish films and mainly offering information on films with Spanish participation in production; the selection criteria are based on having been certified for the first time during the corresponding year. The content offered herein is merely informative and not legally binding as far as the Administration is concerned. © Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte 1 | 55 LARGOMETRAJES 2018 SPANISH FEATURE FILMS - FICCIÓN / FICTION #SEGUIDORES - #FOLLOWERS Dirección/Director: Iván Fernández de Córdoba Productoras/Prod. Companies: NAUTILUS FILMS & PROJECTS, S.L. Intérpretes/Cast: Sara Sálamo, Jaime Olías, Rodrigo Poisón, María Almudéver, Norma Ruiz y Aroa Ortigosa Drama 76’ No recomendada para menores de 12 años / Not recommended for audiences under 12 https://www.facebook.com/seguidoreslapelicula/ ; https://www.instagram.com/seguidoreslapelicula/ Tráiler: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RK5vUNlMJNc ¿QUÉ TE JUEGAS? - GET HER.. -

80 Years of Spanish Cinema Fall, 2013 Tuesday and Thursday, 9:00-10:20Am, Salomon 004

Brown University Department of Hispanic Studies HISP 1290J. Spain on Screen: 80 Years of Spanish Cinema Fall, 2013 Tuesday and Thursday, 9:00-10:20am, Salomon 004 Prof. Sarah Thomas 84 Prospect Street, #301 [email protected] Tel.: (401) 863-2915 Office hours: Thursdays, 11am-1pm Course description: Spain’s is one of the most dynamic and at the same time overlooked of European cinemas. In recent years, Spain has become more internationally visible on screen, especially thanks to filmmakers like Guillermo del Toro, Pedro Almodóvar, and Juan Antonio Bayona. But where does Spanish cinema come from? What themes arise time and again over the course of decades? And what – if anything – can Spain’s cinema tell us about the nation? Does cinema reflect a culture or serve to shape it? This course traces major historical and thematic developments in Spanish cinema from silent films of the 1930s to globalized commercial cinema of the 21st century. Focusing on issues such as landscape, history, memory, violence, sexuality, gender, and the politics of representation, this course will give students a solid training in film analysis and also provide a wide-ranging introduction to Spanish culture. By the end of the semester, students will have gained the skills to write and speak critically about film (in Spanish!), as well as a deeper understanding and appreciation of Spain’s culture, history, and cinema. Prerequisite: HISP 0730, 0740, or equivalent. Films, all written work and many readings are in Spanish. This is a writing-designated course (WRIT) so students should be prepared to craft essays through multiple drafts in workshops with their peers and consultation with the professor. -

Seville Film

SEVILLE IS CINEMA Seville is a city for recording films. Seville has been and continues to be the setting for many national and international television productions and series. We are very pleased to show you the tourist interest places of that have been the setting for these films, as well as information regarding them. How many times have you seen the Plaza de España in “Lawrence of Arabia” or in “Star Wars: Episode II”, and the Casa de Pilatos in “1492: Conquest of Paradise”? Come and visit these prominent landmarks in situ! The Real Alcázar The Real Alcázar is a monumental complex that date back to the Early Middle Ages, constituting the most important civil building in Seville. The surrounding walls, which can be admired from the Plaza del Triunfo, date from the early 10th century. The Patio del Yeso (Courtyard of the Plaster) belongs to the Almohad period between 1147 and 1237. Its ornamentation inspired later Nasrid architecture, but it was the Christian constructions that gave the complex its current appearance. The Gothic Palace, built during the reign of Alfonso X, has been modified due to the work carried out in the 16th century by the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. The most outstanding features in its rooms are the tiled plinths, the work of Cristóbal Augusta between 1577 and 1583, the set of 18th century tapestries depicting the Conquest of Tunis and the reproduction of the Virgin de La Antigua. The Courtroom, built in the middle of the 14th century during the reign of Alfonso XI, is the first example of the Mudejar style in this area, representing a perfect combination of the Islamic and Christian styles. -

Final Appendices

Bibliography ADORNO, THEODOR W (1941). ‘On Popular Music’. On Record: Rock, Pop and the Written Word (ed. S Frith & A Goodwin, 1990): 301-314. London: Routledge (1publ. in Philosophy of Social Sci- ence, 9. 1941, New York: Institute of Social Research: 17-48). —— (1970). Om musikens fetischkaraktär och lyssnandets regression. Göteborg: Musikvetenskapliga in- stitutionen [On the fetish character of music and the regression of listening]. —— (1971). Sociologie de la musique. Musique en jeu, 02: 5-13. —— (1976a). Introduction to the Sociology of Music. New York: Seabury. —— (1976b) Musiksociologi – 12 teoretiska föreläsningar (tr. H Apitzsch). Kristianstad: Cavefors [The Sociology of Music – 12 theoretical lectures]. —— (1977). Letters to Walter Benjamin: ‘Reconciliation under Duress’ and ‘Commitment’. Aesthetics and Politics (ed. E Bloch et al.): 110-133. London: New Left Books. ADVIS, LUIS; GONZÁLEZ, JUAN PABLO (eds., 1994). Clásicos de la Música Popular Chilena 1900-1960. Santiago: Sociedad Chilena del Derecho de Autor. ADVIS, LUIS; CÁCERES, EDUARDO; GARCÍA, FERNANDO; GONZÁLEZ, JUAN PABLO (eds., 1997). Clásicos de la música popular chilena, volumen II, 1960-1973: raíz folclórica - segunda edición. Santia- go: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile. AHARONIÁN, CORIúN (1969a). Boom-Tac, Boom-Tac. Marcha, 1969-05-30. —— (1969b) Mesomúsica y educación musical. Educación artística para niños y adolescentes (ed. Tomeo). 1969, Montevideo: Tauro (pp. 81-89). —— (1985) ‘A Latin-American Approach in a Pioneering Essay’. Popular Music Perspectives (ed. D Horn). Göteborg & Exeter: IASPM (pp. 52-65). —— (1992a) ‘Music, Revolution and Dependency in Latin America’. 1789-1989. Musique, Histoire, Dé- mocratie. Colloque international organisé par Vibrations et l’IASPM, Paris 17-20 juillet (ed. A Hennion. -

Reading for Fictional Worlds in Literature and Film

Reading for Fictional Worlds in Literature and Film Danielle Simard Doctor of Philosophy University of York English and Related Literature March, 2020 2 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to establish a critical methodology which reads for fictional worlds in literature and film. Close readings of literary and cinematic texts are presented in support of the proposition that the fictional world is, and arguably should be, central to the critical process. These readings demonstrate how fictional world-centric readings challenge the conclusions generated by approaches which prioritise the author, the reader and the viewer. I establish a definition of independent fictional worlds, and show how characters rather than narrative are the means by which readers access the fictional world in order to analyse it. This interdisciplinary project engages predominantly with theoretical and critical work on literature and film to consider four distinct groups of contemporary novels and films. These texts demand readings that pose potential problems for my approach, and therefore test the scope and viability of my thesis. I evaluate character and narrative through Fight Club (novel, Chuck Palahniuk [1996] film, David Fincher [1999]); genre, context, and intertextuality in Solaris (novel, Stanisław Lem [1961] film, Andrei Tarkovsky [1974] film, Steven Soderbergh [2002]); mythic thinking and character’s authority with American Gods (novel, Neil Gaiman [2001]) and Anansi Boys (novel, Neil Gaiman [2005]); and temporality and nationality in Cronos (film, Guillermo