Teachers' Survey 2017-2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Peter Q3 2020.Pdf

The Jersey Boys’ lastSee Page 16 march Autumn2020 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Featured What’s new in St Peter? Very little - things have gone Welcomereally quiet it seems, so far as my in-box is concerned anyway. Although ARTICLES the Island has moved to Level 1 of the Safe Exit Framework and many businesses are returning to some kind of normal, the same cannot be said of the various associations within the Parish, as you will see from 6 Helping Wings hope to fly again the rather short contributions from a few of the groups who were able to send me something. Hopefully this will change in the not too distant future, when social distancing returns to normal. There will be a lot of 8 Please don’t feed the Seagulls catching up to do and, I am sure, much news to share in Les Clefs. Closed shops So in this autumn edition, a pretty full 44 pages, there are some 10 offerings from the past which I hope will provide some interesting reading and visual delight. With no Battle of Flowers parades this year, 12 Cash for Trash – Money back on Bottles? there’s a look back at the 28 exhibits the Parish has entered since 1986. Former Constable Mac Pollard shares his knowledge and experiences about St Peter’s Barracks and ‘The Jersey Boys’, and we learn how the 16 The Jersey Boys last march retail sector in the Parish has changed over the years with an article by Neville Renouf on closed shops – no, not the kind reserved for union members only! We also learn a little about the ‘green menace’ in St 20 Hey Mr Bass Man Aubin’s Bay and how to refer to and pronounce it in Jersey French, and after several complaints have been received at the Parish Hall, some 22 Floating through time information on what we should be doing about seagulls. -

The Linguistic Context 34

Variation and Change in Mainland and Insular Norman Empirical Approaches to Linguistic Theory Series Editor Brian D. Joseph (The Ohio State University, USA) Editorial Board Artemis Alexiadou (University of Stuttgart, Germany) Harald Baayen (University of Alberta, Canada) Pier Marco Bertinetto (Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, Italy) Kirk Hazen (West Virginia University, Morgantown, USA) Maria Polinsky (Harvard University, Cambridge, USA) Volume 7 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ealt Variation and Change in Mainland and Insular Norman A Study of Superstrate Influence By Mari C. Jones LEIDEN | BOSTON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Mari C. Variation and Change in Mainland and Insular Norman : a study of superstrate influence / By Mari C. Jones. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25712-2 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-25713-9 (e-book) 1. French language— Variation. 2. French language—Dialects—Channel Islands. 3. Norman dialect—Variation. 4. French language—Dialects—France—Normandy. 5. Norman dialect—Channel Islands. 6. Channel Islands— Languages. 7. Normandy—Languages. I. Title. PC2074.7.J66 2014 447’.01—dc23 2014032281 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 2210-6243 ISBN 978-90-04-25712-2 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25713-9 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. -

Biodiversity Strategy for Jersey

Bio Diversity a strategy for Jersey Forward by Senator Nigel Quérée President, Planning and Environment Committee This document succeeds in bringing together all the facets of Jersey’s uniquely diverse environmental landscape. It describes the contrasting habitats which exist in this small Island and explains what should be done to preserve them, so that we can truly hand Jersey on to future generations with minimal environmental damage. It is a document which should be read by anyone who wants to know more about the different species which exist in Jersey and what should be done to protect them. I hope that it will help to foster a much greater understanding of the delicate balance that should be struck when development in the Island is considered and for that reason this is a valuable supporting tool for the Jersey Island Plan. Introduction Section 4 Loss of biodiversity and other issues Section 1 Causes of Loss of Biodiversity 33 The structure of the strategy Conservation Issues 34 Biodiversity 1 In Situ/Ex Situ Conservation 34 Biodiversity and Jersey 2 EIA Procedures in Jersey 36 Methodology 2 Role of Environmental Adviser 36 Approach 3 International Relations 38 Process 3 Contingency Planning 38 Key International Obligations 3 Current Legislation 5 Section 5 Evaluation of Natural History Sites 5 In situ conservation Introduction 42 Section 2 Habitats 42 Sustainable use Species 46 Introduction 9 The Identification of Key Species 47 General Principles 9 Limitations 48 Scope of Concern 11 Species Action Plans 49 Sample Action Plan 51 -

48 St Saviour Q3 2020.Pdf

Autumn2020 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition 48 farewellA fond Rectorto our wonderful Page 30 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Autumn 2020 St Saviour Parish Magazine p3 From the Editor Featured Back on Track! articles La Cloche is back on track and we have a full magazine. There are some poems by local From the Constable poets to celebrate Liberation and some stories from St Saviour residents who were in Jersey when the Liberation forces arrived on that memorable day, 9th May 1945. It is always enlightening to read and hear of others’ stories from the Occupation and Liberation p4 of Jersey during the 1940s. Life was so very different then, from now, and it is difficult for us to imagine what life was really like for the children and adults living at that time. Giles Bois has submitted a most interesting article when St Saviour had to build a guardhouse on the south coast. The Parish was asked to help Grouville with patrolling Liberation Stories the coast looking for marauders and in 1690 both parishes were ordered to build a guardhouse at La Rocque. This article is a very good read and the historians among you will want to rush off to look for our Guardhouse! Photographs accompany the article to p11 illustrate the building in the early years and then later development. St Saviour Battle of Flowers Association is managing to keep itself alive with a picnic in St Paul’s Football Club playing field. They are also making their own paper flowers in different styles and designs; so please get in touch with the Association Secretary to help with Forever St Saviour making flowers for next year’s Battle. -

Jersey's Spiritual Landscape

Unlock the Island with Jersey Heritage audio tours La Pouquelaye de Faldouët P 04 Built around 6,000 years ago, the dolmen at La Pouquelaye de Faldouët consists of a 5 metre long passage leading into an unusual double chamber. At the entrance you will notice the remains of two dry stone walls and a ring of upright stones that were constructed around the dolmen. Walk along the entrance passage and enter the spacious circular main Jersey’s maritime Jersey’s military chamber. It is unlikely that this was ever landscape landscape roofed because of its size and it is easy Immerse Download the FREE audio tour Immerse Download the FREE audio tour to imagine prehistoric people gathering yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org the history the history here to worship and perform rituals. and stories and stories of Jersey of Jersey La Hougue Bie N 04 The 6,000-year-old burial site at Supported by Supported by La Hougue Bie is considered one of Tourism Development Fund Tourism Development Fund the largest and best preserved Neolithic passage graves in Europe. It stands under an impressive mound that is 12 metres high and 54 metres in diameter. The chapel of Notre Dame de la Clarté Jersey’s Maritime Landscape on the summit of the mound was Listen to fishy tales and delve into Jersey’s maritime built in the 12th century, possibly Jersey’s spiritual replacing an older wooden structure. past. Audio tour and map In the 1990s, the original entrance Jersey’s Military Landscape to the passage was exposed during landscape new excavations of the mound. -

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name Sorted by Proposed for Then Sorted by Site Name Site Use Class Tenure Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Vingtaine Name Address Parish Postcode Controlling Department Parish Disposal Grouville 2 La Croix Crescent Residential Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DA COMMUNITY & CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS Grouville B22 Gorey Village Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EB INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B37 La Hougue Bie - La Rocque Highway Freehold Vingtaine de la Rue Grouville JE3 9UR INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B70 Rue a Don - Mont Gabard Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 6ET INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B71 Rue des Pres Highway Freehold La Croix - Rue de la Ville es Renauds Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DJ INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C109 Rue de la Parade Highway Freehold La Croix Catelain - Princes Tower Road Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE3 9UP INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C111 Rue du Puits Mahaut Highway Freehold Grande Route des Sablons - Rue du Pont Vingtaine de la Rocque Grouville JE3 9BU INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville Field G724 Le Pre de la Reine Agricultural Freehold La Route de Longueville Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE2 7SA ENVIRONMENT Grouville Fields G34 and G37 Queen`s Valley Agricultural Freehold La Route de la Hougue Bie Queen`s Valley Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EW HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES Grouville Fort William Beach Kiosk Sites 1 & 2 Land Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DY JERSEY PROPERTY HOLDINGS -

R Infrastructure Capacity Study Report 2020 ARUP.Pdf

Infrastructure Capacity Study December 2020 Photo credit: BAM Perspectives Government of Jersey Infrastructure Capacity Study Final Report Final | 2020 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 270796-00 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd 13 Fitzroy Street London W1T 4BQ United Kingdom www.arup.com Document verification Job title Infrastructure Capacity Study Job number 270796-00 Document title Final Report File reference Document ref Revision Date Filename Draft 1 07 Jul Description First draft 20 Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name AB / EHW / DE DE KH Signature FinalDraft Issue Oct Filename 2020 Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name AB / EHW / DE DE KH Signature Final March Filename 2021 Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name DE DE KH Signature Final 09 April Filename 2021 Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name EHW EHW KH Signature Issue Document verification with document ✓ | Final | 2020 Government of Jersey Infrastructure Capacity Study Final Report Contents Page Document verification 1 Contents 1 Appendices 3 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Overview of the Bridging Island Plan 4 1.2 Overview of the Infrastructure Capacity Study 4 1.3 Structure 7 2 Context 8 2.1 Infrastructure and its Importance Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.2 Planning for Infrastructure 12 3 Methodology 14 3.1 Scope 14 3.2 Overview of Methodology 15 4 Summary -

Jersey's Military Landscape

Unlock the Island with Jersey Heritage audio tours that if the French fleet was to leave 1765 with a stone vaulted roof, to St Malo, the news could be flashed replace the original structure (which from lookout ships to Mont Orgueil (via was blown up). It is the oldest defensive Grosnez), to Sark and then Guernsey, fortification in St Ouen’s Bay and, as where the British fleet was stationed. with others, is painted white as a Tests showed that the news could navigation marker. arrive in Guernsey within 15 minutes of the French fleet’s departure! La Rocco Tower F 04 Standing half a mile offshore at St Ouen’s Bay F 02, 03, 04 and 05 the southern end of St Ouen’s Bay In 1779, the Prince of Nassau attempted is La Rocco Tower, the largest of to land with his troops in St Ouen’s Conway’s towers and the last to be Jersey’s spiritual Jersey’s maritime bay but found the Lieutenant built. Like the tower at Archirondel landscape Governor and the Militia waiting for it was built on a tidal islet and has a landscape Immerse Download the FREE audio tour Immerse Download the FREE audio tour him and was easily beaten back. surrounding battery, which helps yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org the history the history However, the attack highlighted the give it a distinctive silhouette. and stories and stories need for more fortifications in the area of Jersey of Jersey and a chain of five towers was built in Portelet H 06 the bay in the 1780s as part of General The tower on the rock in the middle Supported by Supported by Henry Seymour Conway’s plan to of the bay is commonly known as Tourism Development Fund Tourism Development Fund fortify the entire coastline of Jersey. -

In the Circle

ALL THETHE TALK TALK OF THE OF THE IN TERRAIN TERRAIN THE CIRCLE Follow us on This newsletter is also Edition No 3 available on our website September 2016 @ JsyPetanque www.thejpa.co.uk Inter Insular to go ahead in October th The inter-insular match standing fixtures. However applications is September 5 between Jersey and JPA chairman Derek Hart Names should be forwarded Guernsey is now scheduled and the Guernsey Club to … for the weekend of 22nd-23rd captain, John Cuthbertson, [email protected]). October. The annual fixture have agreed to try and play The team of 26 players will was under threat because the event over a weekend. It be selected soon afterwards. Condor’s ferry schedules will of course mean the The JPA has indicated that a made it impossible for the extra expense of an over- small subsidy may be made Jersey squad to travel to night stay and the risk that to support travel and Guernsey and return on the some players won’t be accommodation. The same day. It’s a problem available to take part. The Guernsey Club de Pétanque that other clubs and JPA is now asking members has several indoor terrains, associations have had to who are willing to play to so if the weather is poor the grapple with and in some put their names for ward. Inter Insular could still be cases forced to cancel long- The closing date for played under cover. standing fixtures. However JPA chairman Derek Hart and Home Nations to be INSIDE THE CIRCLE held in Jersey in 2018? THIS QUARTER A great year for the sport in Jersey has surely been capped by the island’s first appearance in the Home Nations Championship. -

Appendices Maupertuis

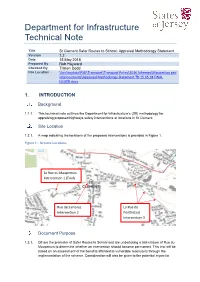

Department for Infrastructure Technical Note Title St Clement Safer Routes to School: Appraisal Methodology Statement Version 1.2 Date 15 May 2018 Prepared By Rob Hayward Checked By Tristen Dodd File Location \\ois\sojdata\PSD\Transport\Transport Policy\2016 Schemes\Maupertuis ped improvements\Appraisal Methodology Statement TD 15.05.18 FINAL ISSUED.docx 1. INTRODUCTION Background 1.1.1. This technical note outlines the Department for Infrastructure’s (DfI) methodology for appraising proposed highways safety interventions at locations in St Clement. Site Location 1.2.1. A map indicating the locations of the proposed interventions is provided in Figure 1. Figure 1 – Scheme Locations La Rue du Maupertuis Intervention 1 (Trial) Rue de Samares La Rue de Intervention 2 Pontlietaut Intervention 3 Document Purpose 1.3.1. DfI are the promoter of Safer Routes to School and are undertaking a trial closure of Rue du Maupertuis to determine whether an intervention should become permanent. This trial will be based on an assessment of the benefits afforded to vulnerable road users through the implementation of the scheme. Consideration will also be given to the potential impact in St Clement Safer Routes to School: Appraisal Methodology Statement neighbouring areas. This includes an assessment for the likelihood for potential increases in accidents brought about by displaced traffic. 1.3.2. There are three interventions detailed in Figure 1 above, however the focus of this note is aligned towards appraising the effect of a trial of Intervention 1. 1.3.3. The locations of the proposed interventions are on Parish Roads, which fall under the administration of the Parish of St Clement. -

Nigel Helps St. Brelade Youth Project Branch Out!

www.labaguette.org.je www.labaguette.org.je THE OFFICIAL PARISH OF ST. BRELADE NEWSLETTER Edition 24 • Summer 2013. Published by the Parish of St. Brelade, Jersey Proposed improvements to St. Aubin revealed Champions!was St Peter/Saint-Hilaire-du-Harcouët. The Twinning Games; The Games proved that the friendship between were off competing with passion and the Parishes and their French Towns is as strong St. Brelade/Granville determination. as ever and there is no doubt that the next event Ten Parishes with their French counterparts in 2 years time will be fun to participate in. The take the trophy from Normandy set out to fight for the “Coupe Twinning Committee of St Brelade would like to by Martha Bernstein Perpetuelle”. Six team members from each of the thank everyone who was involved with the event. Parishes and their french twin did battle in a FINALLY, after almost 3 years of preparation and In the evening there was a Vin D’Honneur planning the Twinning Games were opened at variety of games including a modern twist on the sponsored by the Twinning Association of St Les Quennevais Sports Grounds on Saturday 8th old favourite egg and spoon race where the June by the Bailiff Sir Michael Birt. competitors had a large spoon and a tennis ball Brelade for all the competitors and invited to run with. supporters and dignitaries from each Parish. The Official Games started with a procession of Members of the Association had worked hard to all the competitors lead by a Scots Piper and Miss On what was otherwise a sunny day there was a Battle of Flowers 2013. -

No.3 Les Landes De L'est SSI.Pdf

Les Landes de L’Est Site of Special (Ecological) Interest Introduction Les Landes de L’Est, otherwise known as Les Landes, is one of the Island’s largest Sites of Special Interest (SSI), covering 102 hectares and forming the north-west corner of the Jersey National Park. It is the largest single block of maritime heathland anywhere in the Channel Islands and offers visitors a feeling of wildness and remoteness. The site’s location provides an important ecological link between St Ouen’s Bay and the north coast, supporting a range of habitats and species, some of which are unique to the area. Large parts of the site are in public ownership, but the SSI incorporates other areas of private and common land. The site is an open plateau lying 80m above mean sea level and Spotted Cat's-ear the underlying rock is primarily granite, resulting in thin and acidic soils, which in turn heavily influences the vegetation which favours these conditions. The hardness of the bedrock has led to the creation of the dramatic, steep cliffs which we see today. The openness and feeling of wildness on offer are fantastic with wonderful views across the mauves and yellows of the gorse and heather towards the other Channel Islands to the north. Jersey’s climate is oceanic, and the north-west coast of Jersey is wide-open to the full force of Atlantic gales making Les Landes one of the most exposed areas of the Island. The wind is usually wet and salty, which has an effect particularly on the vegetation in the area.