Techniques & Culture, 35-36 | 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of ENVIRONMENT Volume-10, Issue-1, 2020/21 ISSN 2091-2854 Received:3 Dec 2020 Revised:24 Feb 2021 Accepted:26 Feb 2021

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENT Volume-10, Issue-1, 2020/21 ISSN 2091-2854 Received:3 Dec 2020 Revised:24 Feb 2021 Accepted:26 Feb 2021 EVALUATION OF CONTAMINATION AND ACCUMULATION OF HEAVY METALS IN THE DHALESWARI RIVER SEDIMENTS, BANGLADESH Abdullah Al Mamun1, †, Protima Sarker 1, 2,*, †, Md. Shiblur Rahaman1, 3, Mohammad Mahbub Kabir1, 4 and Masahiro Maruo2 1Department of Environmental Science and Disaster Management, Noakhali Science and Technology University, Noakhali-3814, Bangladesh. 2School of Environmental Science, University of Shiga Prefecture, 2500 Hassakacho, Hikone, Shiga 522-8533, Japan. 3Department of Environmental and Preventive Medicine, Jichi Medical University School of Medicine, 3311-1 Yakushiji, Shimotsuke, Tochigi-329-0498, Japan. 4Research Cell, Noakhali Science and Technology University, Noakhali-3814, Bangladesh. *Corresponding author: [email protected] †Authors contributed equally to the manuscript Abstract The Dhaleswari river is considered as one of the most important rivers of Bangladesh due to its geographical location and ecological services. The present study attempts to evaluate the degree of heavy metal pollution, contamination, and accumulative behavior in the sediment of the Dhaleswari river. The sediment samples were collected from fifteen different locations of the Dhaleswari river. Heavy metals were analyzed using the Flame Atomic Spectrophotometer (FAAS). The mean concentrations of Zn, Cu, Cr, Pb and Cd were 131.9, 48.89, 43.16, 33.23 and 0.37 mgkg-1, respectively. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Sediment Quality Guideline, the sediment of most of the locations were not polluted for Pb and Cd. But S-11 location for Cd (0.8 mg kg-1) was highly polluted. -

![[-] Subarnarekha Basin](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0370/subarnarekha-basin-660370.webp)

[-] Subarnarekha Basin

GOVT OF ODISHA DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES SUBARNAREKHA IRRIGATION PROJECT ODISHA GENERAL HEALTH REPORT ON SUBARNAREKHA BASIN Laxmiposi. Chief Engineer & Basin Manager, March’2017. Subarnarekha & Budhabalanga Basin . 1 STATUS OF SUBARNAREKHA BASIN Subarnarekha River originates near Nagri village of the Chhotnagpur plateau of Jharkhand. Total length of the river from its origin to its outfall into Bay of Bengal is 446.12 km, including 79 km inside Odisha. The prominent tributaries of the Subarnarekha are; 1. Raru river. 2. Kanchi river 3. Damra river 4. Karru river 5. Kharkhai river 6. Chinguru river 7. Karakari river 8. Gurma river 9. Garra river 10. Singaduba river 11. Kodia river 12. Dulunga river 13. Khaijori river The Co-Basin States of Subarnarekha River are Bihar (Now Jharkhand), West Bengal and Odisha. The list of Projects coming under Subarnarekha Basin are as under. Details of On-going & Proposed Irrigation Schemes in Subarnarekha Basin in Jharkhand :- Sl No. Name of the River Name of the Scheme On-Going Scheme 1 Subarnarekha River Chandil reservoir scheme (completed) 2 Subarnarekha River Galudih Barrage Scheme(completed) 3 Kanchi River Kanchi reservoir scheme(completed) 4 Surangi Nala Surangi reservoir scheme 5 Raru River Raru reservoir scheme 6 Raisa Nadi Raisa reservoir scheme 7 Taina River Taina reservoir scheme Proposed Schemes 1 Bamini Nala Bamini reservoir scheme 2 Bara Nala Bara Nala reservoir scheme 3 Kanchi Nadi Silda reservoir scheme 4 Gara Nala Bhagbandi reservoir scheme 5 Kankuram Nala Purunapani reservoir scheme 6 Dudh Nala Turukdih reservoir scheme 7 Kharsoti Nala Jambad Barrage Scheme 8 Jamur River Jamur reservoir scheme 9 Sanka River Sudurpur weir 10 Sobha Nadi Sobha weir 2 Details of On-going & Proposed Irrigation Schemes in Kharkai Sub-Basin in Jharkhand Sl No. -

Study of Water Quality of Swarnrekha River, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 Study of water quality of Swarnrekha River, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India Suresh Kumar 1, Sujata kumari 2 1. Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee University, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India 2. Ranchi University, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract The name of river “Swarnrekha” is given after in the ancient period due to the occurrence of “gold streaks” in the river water or river sediments. The river originated from a “seepage cum underground well”, locally called “Ranichuan” at the Nagari village of the Ranchi district. It is the first river which originates from seepage well locally called “Chuan” basically a great seepage well having a catchment area. According to Hindu Mythology, it is said that this Ranichuan was carved by the lord Rama by his arrow while Sita, his wife, was feeling thirsty during the period of Ramayana. In this way, we say that the river is basically originated from the seepage water or ground water. It travels towards the south east of Ranchi to East Singhbhum to Sarikhela and finally confluence with Damodar River at cretina mouth of the river. Previously, it was very pure form of drinkable water and day by day its quality deteriorated due to the anthropogenic activities and ultimately whole stretches of the river turned into garbage field and most polluted water streams. So, now we can say the river turned from gold streak to garbage streak and not suitable for the human beings without treatment. Physical, Chemical and microbial properties of the river water from point of origin to the lower chutia is deterioted such as water is very clean at the site of origin and became gradually hazy and dirt as it crosses through the habitants or settlements. -

Assessment of Water Quality Index in Subarnarekha River Basin in and Around Jharkhand Area

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 8, Issue 11 Ver. I (Nov. 2014), PP 39-45 www.iosrjournals.org Assessment of Water Quality Index in Subarnarekha River Basin in and around Jharkhand Area Nirmal Kumar Bhuyan1, Baidhar Sahu2, Swoyam P.Rout3 1Water Quality Laboratory,Central Water Commission, Bhubaneswar,751022 2Fmr.Reader Department of Chemistry, Ravenshaw University, Cuttack,753003 3Fmr.Professor Dept. of Chemistry, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar,751007 Email of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: The present investigation is aimed at assessing the current water quality standard along the Subarnarekha river in Jharkhand .Eight samples were collected along the stretches of Subarnarekha basin during the period (Water Year) June-2012 to May-2013 on the first working day of every month.Various physico-chemical parameters like pH,TDS, EC,DO, BOD, Total Hardness, Total alkalinity sodium,potassium,calcium,magnesium etc. were analysed. Eight parameters namely pH,Dissolved Oxygen, Biochemical Oxygen Demand ,Nitrate,Phosphate,Total Dissolved Solids and Faecal Colliform were considered to compute Water Quality Index (WQI) based on National Sanitation Foundation studies.Our findings highlighted the deterioration of water quality in the rivers due to industrialization and human activities. Key Words: NSF Water Quality Index, TDS, EC, DO, BOD, Total Hardness,Faecal Colliform I. Introduction The study is carried out in Subarnarekha river which flows through the East Singhbhum district,which is one of the India’s important industrialized areas known for ore mining, steel production, power generation, cement production and other related activities.The Subarnarekha river is the eighth river in India by its flow(12.37 billion m3/year) and length. -

Central Water Commission Compiled the Siltation Data of 07 Reservoirs in the State

Media Release Central Water Commission Compiled the Siltation Data of 07 Reservoirs in the State MoS Water Resources Replied to RS MP Shri Parimal Nathwani November 28, 2016: The Central Water Commission (CWC) has complied the siltation data of 07 reservoirs in the State of Jharkhand. CWC has complied siltation data of selected 243 reservoirs in the country. Jharkhand is one of the seven states where Dam Rehabilitation and Improvement Programme (DRIP) is implemented. The Minister of State for Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan informed Rajya Sabha on November 28, 2016 in a reply to the question raised by Rajya Sabha member Shri Parimal Nathwani. According to the statement of the minister, the CWC has compiled siltation data of seven reservoirs in Jharkhand namely Getalsud on Subarnarekha river, Konar on Konar river, Maithon on Barakar river, Mayurakshi on Mayurakshi river, Panchet and Tenughat on Damodar river and Tilaiya on Barakar river. There are three dams of Jharkhand included under DRIP for improvement of safety level, said the statement. The statement also said that DRIP envisages the enhancement of safety and operational performance of existing 225 dams, in addition to building the institutional capacity of the Dam Safety Organisations of the participating states and Central Dam Safety Organisation in CWC. The project is being implemented with financial assistance from World Bank at an estimated cost of Rs. 2100 Crore, in seven states of India, namely, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Jharkhand (DVC) and Uttarakhand (UJVNL). The project started with effect from 18th April, 2012 for over a period of six years, said the statement. -

District Survey Report, Purulia District, West Bengal 85

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (For mining of minor minerals) As per Notification No. S.O.3611 (E) New Delhi dated 25TH Of July 2018 Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) PREPARED BY: RSP GREEN DEVELOPMENT AND LABORATORIES PVT. LTD. ISO 9001:2015 & ISO 14001:2015 Certified Company QCI-NABET ACCREDITED CONSULTANT JANUARY, 2021 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT DISTRICT SURVEY DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT, JHARGRAM DISTRICT, WEST BENGAL CONTENTS SL. TOPIC DETAILS PAGE NO. NO CONTENT I - II ABBREVIATIONS USED III - IV LIST OF TABLES V - VI LIST OF MAPS VII LIST OF ANNEXURES VIII CONFIDENTIALITY CLAUSE IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENT X FIELD PHOTOGRAPHS XXX 1 PREFACE 1 2 INTRODUCTION 2 3 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE DISTRICT 4 - 16 a. General information 3 b. Demography 3 - 7 c. Climate condition 7 d. Rain fall (month wise) and humidity 8 e. Topography and terrain 8 - 9 f. Water course and hydrology 9 - 10 g. Ground water development 10 - 13 h. Drainage system (general) 13 i. Cropping pattern 13 - 15 j. Landform and seismicity 15 k. Flora 15 - 16 l. Fauna 16 4 PHYSIOGRAPHY OF THE DISTRICT 17 - 22 o General landform 17 o Soil 17 - 19 o Rock pattern 19 - 20 o Different geomorphological units 20 o Drainage basins 21 - 22 5 LAND USE PATTERN OF THE DISTRICT 23 - 30 . Introduction 23 - 26 a. Forest 26 - 27 b. Agriculture & Irrigation 27 - 29 c. Horticulture 29 d. Mining 30 6 GEOLOGY 31 - 34 Regional geology 31 - 33 Local geology 33 - 34 7 MINERAL WEALTH 35 - 37 Overview of the mineral 35 - 37 resources (covering all minerals) I PREPARED BY: RSP GREEN DEVELOPMENT AND LABORATORIES PVT. -

ANJU KUMARI, RAVINDER SINGH and N

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eprints@NML Journal of Metallurgy and Materials Science, Vol. 58, No. 3, July-September 2016, pp. 159-166 Printed in India, © NML, ISSN 0972-4257 Seasonal variation of heavy metals in Subarnarekha River at Jamshedpur, East Singhbhum, Jharkhand ANJU KUMARI, RAVINDER SINGH and N. G. GOSWAMI1 PG Deptt., Kolhan University, Chaibasa, Jharkhand, India-833202 1CSIR-National Metallurgical Laboratory, Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India-831007 Abstract : The present investigation is aimed at assessing the amount of heavy metals and current water quality standard along the Subarnarekha river in Jharkhand. Three samples were collected along the stretches of Subarnarekha basin during the period : Jan-Dec, 2015, on the first week of every month. The concentrations Cu, Pb, Ni, Zn, Cr, Co, Sr, Cd and Fe were determined using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry for seasonal fluctuation, source apportionment and heavy metal pollution indexing. The results demonstrated that concentrations of the metals showed significant seasonality. To assess the composite influence of all the considered metals on the overall quality of the water, heavy metal pollution indices were calculated. The deterioration of water quality and enhanced concentrations of certain metals in the Subarnarekha River near industrial and mining establishments may be attributed to anthropogenic contribution from the industrial and mining activities of the area. Various physicochemical parameters like pH, TDS, EC, DO, BOD, Total Hardness, Total alkalinity sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium etc. were also analysed. Eight parameters namely pH, Dissolved Oxygen, Biochemical Oxygen Demand, Nitrate, Phosphate, Total Dissolved Solids and Faecal Colliform were considered to compute Water Quality Index (WQI) based on National Sanitation Foundation studies and discussed. -

Assessment of Water Quality of Subarnarekha River in Balasore Region, Odisha, India

Current World Environment Vol. 9(2), 437-446 (2014) Assessment of Water Quality of Subarnarekha River In Balasore Region, Odisha, India A.A. KARIM*1 and R.B. PANDA2 1Department of Environment and Sustainability, CSIR-Institute of Minerals and Materials Technology, Bhubaneswar - 751013, Odisha, India. 2P.G Department of Environmental Science, F.M University, Balasore-756020, Odisha, India. http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.9.2.27 (Received: Feburary 07, 2014; Accepted: May 21, 2014) ABSTRACT The present study was carried out to determine the water quality status of Subarnarekha River at Balasore region during pre-project period as Kirtania Port is proposed in this area. River water samples were analysed for physico-chemical parameters by following standard methods (APHA 1985) and the results showed their variations as follows: pH 7.3-7.8,Temperature 26.7-28.20C, Electrical Conductivity 392-514 µ mho ,Total suspended solids 118-148 mg/l, Total dissolved solids 241-285 mg/l, Alkalinity 27.3-42 mg/l, Total Hardness 64.63-114.06 mg/l, Calcium 24.6-32 mg/l, Magnesium 9.72-13.8 mg/l, Dissolved Oxygen 4.6-5.3 mg/l, Biochemical oxygen demand 1.1-3.39 mg/l, Chemical oxygen demand 53-147 mg/l, Nitrates 0.4-1.06 mg/l, Phosphates 0.86-2.4 mg/l, Sulphates 113-143 mg/l, Chlorides 26.32-36.63 mg/l, Iron 0.224-0.464 mg/l, Chromium 0.008-0.016 mg/l. The analysed physico-chemical parameters were almost not exceeded the maximum permissible limit of Indian standards (IS: 10500). -

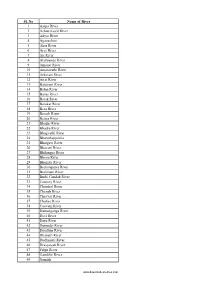

List of Rivers in India

Sl. No Name of River 1 Aarpa River 2 Achan Kovil River 3 Adyar River 4 Aganashini 5 Ahar River 6 Ajay River 7 Aji River 8 Alaknanda River 9 Amanat River 10 Amaravathi River 11 Arkavati River 12 Atrai River 13 Baitarani River 14 Balan River 15 Banas River 16 Barak River 17 Barakar River 18 Beas River 19 Berach River 20 Betwa River 21 Bhadar River 22 Bhadra River 23 Bhagirathi River 24 Bharathappuzha 25 Bhargavi River 26 Bhavani River 27 Bhilangna River 28 Bhima River 29 Bhugdoi River 30 Brahmaputra River 31 Brahmani River 32 Burhi Gandak River 33 Cauvery River 34 Chambal River 35 Chenab River 36 Cheyyar River 37 Chaliya River 38 Coovum River 39 Damanganga River 40 Devi River 41 Daya River 42 Damodar River 43 Doodhna River 44 Dhansiri River 45 Dudhimati River 46 Dravyavati River 47 Falgu River 48 Gambhir River 49 Gandak www.downloadexcelfiles.com 50 Ganges River 51 Ganges River 52 Gayathripuzha 53 Ghaggar River 54 Ghaghara River 55 Ghataprabha 56 Girija River 57 Girna River 58 Godavari River 59 Gomti River 60 Gunjavni River 61 Halali River 62 Hoogli River 63 Hindon River 64 gursuti river 65 IB River 66 Indus River 67 Indravati River 68 Indrayani River 69 Jaldhaka 70 Jhelum River 71 Jayamangali River 72 Jambhira River 73 Kabini River 74 Kadalundi River 75 Kaagini River 76 Kali River- Gujarat 77 Kali River- Karnataka 78 Kali River- Uttarakhand 79 Kali River- Uttar Pradesh 80 Kali Sindh River 81 Kaliasote River 82 Karmanasha 83 Karban River 84 Kallada River 85 Kallayi River 86 Kalpathipuzha 87 Kameng River 88 Kanhan River 89 Kamla River 90 -

Iiilll~111111!1 IMJI~TII 1'(111111111 T

. -~JIA"lll~IIIIIIGl J'I'~~ -IIilll~111111!1 IMJI~TII 1'(111111111 t , + I. [ . _. _ _ . I . l . I / / / . / . / -- ~ r : f I I / / / / ". Health of Inland Aquatic Resources and its Impact on Fisheries A. P. Sharma M. K. Das S. Samanta Policy Paper - 4 February - 2014 Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) Barrackpore, Kolkata-700 120, West Bengal Health 0 Inland Aquatic Resources and its Impa t on Fisheries 1Ul!I' UlIIIIIC IIlIIICIS III m.,. IISIIIIES A. P. Sharma M. K. Das S. Samanta © 2014 Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute, Barrackpore ISSN : .970-616X Material c1ntained in this Policy Paper may not be reproduced, in any form, without th1 permission of the publisher Published by Prof. A. P Sharma Director Central I land Fisheries Research Institute Barrackp re. Kolkata - 700120, West Bengal Photographs by : S.Bhow ick Printed at : Eastern rinting Processor 93, Dakshindari Road Kolkata 700048 CONTENTS SI. No. li pic Page No. 1. IOdUCliO' 1 2. H bitat status of inland water bodies for fish 1 2.1 1 2.2 R servoirs 17 2.3 l~FI odplain wetlands 20 3. I pact on fisheries 23 3.1 J ter quality alteration 23 3.1.1 23 3.1.2 p 23 3.1.3 24 3.1.4 24 3.1.5 25 3.1.5.1 Se age 25 3.1.5.2 25 3.1.5.3 TSJ+spended""" solids 25 3.1.5.4 H avy metals 25 3.2 HJdrolOgiCal alteration 26 3.2.1 Dams and fish passes 26 3.2.2 27 3.3 La d use pattern alteration 27 3.4 Cli ate change 29 3.5 In asion of exotic fish species in Indian rivers 29 4. -

Golden Jubilee of Independence Issue

Golden Jubilee of Independence Issue MIJST MIST International Journal of Science and Technology EDITORIAL BOARD CHIEF PATRON Major General Md Wahid-Uz-Zaman, ndc, aowc, psc, te Commandant Military Institute of Science and Technology (MIST) Dhaka, Bangladesh EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Dr. Firoz Alam Professor School of Engineering, RMIT University Melbourne, Australia EXECUTIVE EDITOR Dr. A.K.M. Nurul Amin Professor, Industrial and Production Engineering, Military Institute of Science and Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lt Col Md Altab Hossain, PhD, EME Assoc. Professor, Nuclear Science and Engineering, Military Institute of Science and Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh Lt Col Muhammad Nazrul Islam, PhD, Sigs Assoc. Professor, Computer Science and Engineering, Military Institute of Science and Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh COPY EDITOR Dr. Md Enamul Hoque Professor, Biomedical Engineering, Military Institute of Science and Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh EDITORIAL ADVISOR Col Molla Md. Zubaer, te Military Institute of Science and Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh SECTION EDITORS Dr G. M. Jahid Hasan Dr. M. A. Taher Ali Dr. Muammer Din Arif Professor (CE), MIST, Professor (AE), MIST, Assistant Professor (IPE), MIST, Dhaka, Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Lt Col Khondaker Sakil Ahmed, PhD Maj Osman Md Amin, PhD, Engrs Dr. AKM Badrul Alam Associate Professor (CE), MIST, Associate Professor (NAME), MIST, Associate Professor (PME), MIST, Dhaka, Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Dr. Md. Mahbubur Rahman Maj Kazi Shamima Akter, PhD, Engrs Lt Col Brajalal Sinha, PhD, AEC Professor (CSE), MIST, Associate Professor (EWCE), MIST, Associate Professor (Sc & Hum), MIST, Dhaka, Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Brig Gen A K M Nazrul Islam, PhD Md. Sazzad Hossain Lt Col Palash Kumar Sarker, PhD, Sigs Professor (EECE), MIST, Associate Professor (Arch), MIST, Associate Professor (Sc & Hum), MIST, Dhaka, Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Mr. -

Hkkjr Ljdkj Dsunzh; Ty Vk;Ksx Tyo"Kz Iqflrdk

[kaM&3 Volume-III dsoy dk;kZy; mi;ksx gsrq ( ) (FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY) Hkkjr ljdkj GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI t y ’fDr ea=ky; ty lalk/ku unh fodkl vkSj xaxk laj{k.k foÒkx , DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENTdsUnzh; & GANGAty vk;ksx REJUVENATION CENTRAL WATER COMMISSION tyo"kZ iqfLrdk WATER YEAR BOOK twu 2018 ebZ 2019 ( - ) (June 2018 - May 2019) cSrj.kh] lqcZ.kjs[kk ,oa cw<kcyax csflu BAITARANI, SUBARNAREKHA & BURHABALANG BASIN Tky foKkuh; izs{k.k ifjeaMy HYDROLOGICALHkqous j OBSERVATION CIRCLE ’o (BHUBANESWAR) September: 2019 [kaM&3 Volume-III tyo"kZ iqfLrdk WATER YEAR BOOK twu 2018 ls ebZ 2019 ( ) (June,2018 – May,2019) cSrj.kh] lqcZ.kjs[kk ,oa cw<kcyax csflu BAITARANI, SUBARNAREKHA & BURHABALANG BASIN FOREWORD Proper assessment, analysis and compilation of hydro -meteorological data are essential for planning and management of precious water resources, which is vital not only for economic development but also for providing basic needs for such a large population of our country. Water reaches the land -mass through precipitation, a part of which evaporates, a portion of it percolates into ground as natural ground water and the excess runoff flows through rivulets and rivers and drain into the sea. Central Water Commission (CWC), an apex technical Organisation of Government of India for surface water resources, carries out systematic collection of hydro -meteorological data and assessment of surface water as one of its prime functions. Hydro-meteorological observation stations have been established by CWC in almost all the river basins of India in a phased manner.