Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:10:37AM Via Free Access 2 Pires, Strange and Mello Several Afro- and Indo-Guianese Populations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorandum of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on The

Memorandum of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on the Application filed before the International Court of Justice by the Cooperative of Guyana on March 29th, 2018 ANNEX Table of Contents I. Venezuela’s territorial claim and process of decolonization of the British Guyana, 1961-1965 ................................................................... 3 II. London Conference, December 9th-10th, 1965………………………15 III. Geneva Conference, February 16th-17th, 1966………………………20 IV. Intervention of Minister Iribarren Borges on the Geneva Agreement at the National Congress, March 17th, 1966……………………………25 V. The recognition of Guyana by Venezuela, May 1966 ........................ 37 VI. Mixed Commission, 1966-1970 .......................................................... 41 VII. The Protocol of Port of Spain, 1970-1982 .......................................... 49 VIII. Reactivation of the Geneva Agreement: election of means of settlement by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, 1982-198371 IX. The choice of Good Offices, 1983-1989 ............................................. 83 X. The process of Good Offices, 1989-2014 ........................................... 87 XI. Work Plan Proposal: Process of good offices in the border dispute between Guyana and Venezuela, 2013 ............................................. 116 XII. Events leading to the communiqué of the UN Secretary-General of January 30th, 2018 (2014-2018) ....................................................... 118 2 I. Venezuela’s territorial claim and Process of decolonization -

DIANA PATON & MAARIT FORDE, Editors

diana paton & maarit forde, editors ObeahThe Politics of Caribbean and Religion and Healing Other Powers Obeah and Other Powers The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing diana paton & maarit forde, editors duke university press durham & london 2012 ∫ 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Katy Clove Typeset in Arno Pro by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Newcastle University, which provided funds toward the production of this book. Foreword erna brodber One afternoon when I was six and in standard 2, sitting quietly while the teacher, Mr. Grant, wrote our assignment on the blackboard, I heard a girl scream as if she were frightened. Mr. Grant must have heard it, too, for he turned as if to see whether that frightened scream had come from one of us, his charges. My classmates looked at me. Which wasn’t strange: I had a reputation for knowing the answer. They must have thought I would know about the scream. As it happened, all I could think about was how strange, just at the time when I needed it, the girl had screamed. I had been swimming through the clouds, unwillingly connected to a small party of adults who were purposefully going somewhere, a destination I sud- denly sensed meant danger for me. Naturally I didn’t want to go any further with them, but I didn’t know how to communicate this to adults and ones intent on doing me harm. -

Scholarship 2004–2005

SCHOLARSHIP 2004–2005 The 2004–2005 edition of the Duquesne University Scholarship bibliography was produced at the Gumberg Library, under the direction of Laverna Saunders, University Librarian. The bibliography was compiled by Matthew Boyer, Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Coordinator. Editorial assistance was provided by Leslie Lewis, Barbara Adams, and Allison Brungard. Duquesne University 600 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15282 http://www.duq.edu © 2006 CONTENTS Letter from the President....................................................................................................................v Publications...........................................................................................................................................1 McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts ........................................................3 Bayer School of Natural and Environmental Sciences..........................................................16 School of Law..............................................................................................................................23 A. J. Palumbo School of Business Administration and John F. Donahue Graduate School of Business ......................................................................................................................25 Mylan School of Pharmacy........................................................................................................29 Mary Pappert School of Music..................................................................................................32 -

Statement by Honorable Pauline Sukhai M.P Minister of Amerindian

Statement by Honorable Pauline Sukhai M.P Minister of Amerindian Government of Guyana To the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of indigenous People Fifth Session, July 11, 2012 Good Morning Madam Chairperson Guyana strongly believe that the rights to land provides recognition, respect and the support for the of resting and revival of indigenous culture and languages. One conditions for consideration in the titling of lands to Amerindians in Guyana is that of the relationship with the land for sacred, ceremonial and heritage site. In sharing the experiences and efforts that are advanced currently by the Guyana Government: Guyana declared in 1995 the month of September as Amerindian Heritage month, in recognition of the indigenous people as being equal, to ensure the recognition of indigenous peoples as part of our diverse ethnic nation. Annually Amerindians promotes the cultural heritage, achievements and contributions of the people. Highlighted are Amerindians music and arts; Indigenous culinary art; literature and languages. Special recognition are afforded to renowned Amerindians both past and present. Importantly, the Walter Roth museum displays and provides a good perspective on the Amerindian ways of life and displays an array of exhibits and artifacts on Amerindians. In Georgetown our capital city, the Umana Yana (the Benab-the traditional meeting place) and the Amerindian village are constructed strategically and are used for international and local conferences, cultural shows and various diverse events of Guyanese people. Both buildings displays the unique Amerindian architecture style. The Ministry of Amerindian Affairs operates a craft shop and continues to support the sale of indigenous craft, arts, thereby providing a marketing opportunity and promotion of Amerindians craftsmanship. -

By Obianuju Ugwu-Oju CLINOTHEMS of the CRETACEOUS BERBICE

CLINOTHEMS OF THE CRETACEOUS BERBICE CANYON, OFFSHORE GUYANA by Obianuju Ugwu-Oju A thesis submitted to the Faculty and the Board of Trustees of the Colorado School of Mines in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geology). Golden, Colorado Date ____________________________ Signed ____________________________ Obianuju Ugwu-Oju Signed ____________________________ Dr. Lesli Wood Thesis Advisor Golden, Colorado Date ____________________________ Signed ____________________________ Dr. M. Stephen Enders Head Department of Geology and Geological Engineering ii ABSTRACT The Berbice Canyon of offshore Guyana evolved in the late Cretaceous in proximity to a margin that was separating from the African margin in response to the opening of the northern South Atlantic Ocean. The Berbice would be considered a shelf-incised canyon in the nomenclature of Harris and Whiteway, 2011. This study examines the nature of the canyon morphology, fill phases and fill architecture within the Berbice Canyon using ~7000 km2 of 3D seismic time and depth data, as well as chronostratigraphic data from Horseshoe-01 well drilled adjacent to the canyon fill. The Berbice displays composite canyon development with multiple phases of cut and fill. There are six primary incisional surfaces exhibiting a maximum width of 33km, a maximum relief of 1250 m and a composite maximum relief of 2650 m when decompaction is factored. The western side of the canyon system is primarily modified through destructional activities such as scalloping and side wall failures while the eastern side is primarily modified through constructional progradational activities. There are clinothems deposited within the canyon between incisional surfaces I3 and I4, primarily on the eastern side. -

PHD DISSERTATION Shanti Zaid Edit

“A DOG HAS FOUR LEGS BUT WALKS IN ONE DIRECTION:” MULTIPLE RELIGIOUS BELONGING AND ORGANIC AFRICA-INSPIRED RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS IN ORIENTE CUBA By Shanti Ali Zaid A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of African American and African Studies—Doctor of Philosophy Anthropology—Dual Major 2019 ABSTRACT “A DOG HAS FOUR LEGS BUT WALKS IN ONE DIRECTION:” MULTIPLE RELIGIOUS BELONGING AND ORGANIC AFRICA-INSPIRED RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS IN ORIENTE CUBA By Shanti Ali Zaid If religion is about social cohesion and the coordination of meaning, values, and motivations of a community or society, hoW do communities meaningfully navigate the religious domain in an environment of multiple religious possibilities? Within the range of socio-cultural responses to such conditions, this dissertation empirically explores “multiple religious belonging,” a concept referring to individuals or groups Whose religious identity, commitments, or activities may extend beyond a single coherent religious tradition. The project evaluates expressions of this phenomenon in the eastern Cuban city of Santiago de Cuba With focused attention on practitioners of Regla Ocha/Ifá, Palo Monte, Espiritismo Cruzado, and Muertería, four organic religious traditions historically evolved from the efforts of African descendants on the island. With concern for identifying patterns, limits, and variety of expression of multiple religious belonging, I employed qualitative research methods to explore hoW distinctions and relationships between religious traditions are articulated, navigated, and practiced. These methods included directed formal and informal personal intervieWs and participant observations of ritual spaces, events, and community gatherings in the four traditions. I demonstrate that religious practitioners in Santiago manage diverse religious options through multiple religious belonging and that practitioners have strategies for expressing their multiple religious belonging. -

A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 7 Issue 3 Papers from NWAV 29 Article 20 2001 A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos Peter Snow Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Snow, Peter (2001) "A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 7 : Iss. 3 , Article 20. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss3/20 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss3/20 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos This working paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss3/20 A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos 1 Peter Snow 1 Introduction In its ideal form, the phenomenon of the creole continuum as originally described by DeCamp (1971) and Bickerton (1973) may be understood as a result of the process of decreolization that occurs wherever a creole is in direct contact with its lexifier. This contact between creole languages and the languages that provide the majority of their lexicons leads to synchronic variation in the form of a continuum that reflects the unidirectional process of decreolization. The resulting continuum of varieties ranges from the "basilect" (most markedly creole), through intermediate "mesolectal" varie ties (less markedly creole), to the "acrolect" (least markedly creole or the lexifier language itself). -

THE CULTURE FACTOR: the Effects on Healthcare Decisions Among Guyanese Men Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice

THE CULTURE FACTOR: The Effects on Healthcare Decisions Among Guyanese Men Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 7 © Center for Health Disparities Research, School of Public Health, University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2021 THE CULTURE FACTOR: The Effects on Healthcare Decisions Among Guyanese Men Harrynauth Persaud , CUNY York College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp Part of the Community Health and Preventive Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Harrynauth (2021) "THE CULTURE FACTOR: The Effects on Healthcare Decisions Among Guyanese Men," Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp/vol14/iss1/7 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Article in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CULTURE FACTOR: The Effects on Healthcare Decisions Among Guyanese Men Abstract Culture, religious beliefs, and ethnic customs, all play a role in how patients make healthcare decisions. -

Slave Trading and Slavery in the Dutch Colonial Empire: a Global Comparison

rik Van WELie Slave Trading and Slavery in the Dutch Colonial Empire: A Global Comparison INTRODUCTION From the early seventeenth to the mid-nineteenth century, slavery played a fundamental role in the Dutch colonial empire.1 All overseas possessions of the Dutch depended in varying degrees on the labor of slaves who were imported from diverse and often remote areas. Over the past decades numer- ous academic publications have shed light on the history of the Dutch Atlantic slave trade and of slavery in the Dutch Americas.2 These scholarly contribu- tions, in combination with the social and political activism of the descen- dants of Caribbean slaves, have helped to bring the subject of slavery into the national public debate. The ongoing discussions about an official apology for the Dutch role in slavery, the erection of monuments to commemorate that history, and the inclusion of some of these topics in the first national history canon are all testimony to this increased attention for a troubled past.3 To some this recent focus on the negative aspects of Dutch colonial history has already gone too far, as they summon the country’s glorious past to instill a 1. I would like to thank David Eltis, Pieter Emmer, Henk den Heijer, Han Jordaan, Gerrit Knaap, Gert Oostindie, Alex van Stipriaan, Jelmer Vos, and the anonymous reviewers of the New West Indian Guide for their many insightful comments. As usual, the author remains entirely responsible for any errors. This article is an abbreviated version of a chapter writ- ten for the “Migration and Culture in the Dutch Colonial World” project at KITLV. -

Algeria Ancestors Angola Animals in African Folklore Arabic Folk Literature of North Africa Architecture Archives of Traditional Music Ashanti Astronomy

A Algeria Ancestors Angola Animals in African Folklore Arabic Folk Literature of North Africa Architecture Archives of Traditional Music Ashanti Astronomy back to top B Bamana Banjo: African Roots Bao Bascom, William Basketry, Africa Basketry, African American Beadwork Benin Birth and Death Rituals among the Gikuyu Blacksmiths: Dar Zaghawa of the Sudan Blacksmiths: Mande of Western Africa Body Arts: African American Arts of the Body Body Arts: Body Decoration in Africa Body Arts: Hair Sculpture Botswana Burkina Faso Burundi back to top C Callaway, Bishop Henry Cameroon Cape Verde Cardinal Directions Caribbean Verbal Arts Carnivals and African American Cultures Cartoons Central African Folklore Central African Republic Ceramics Ceramics and Gender Chad Chief Children's folklore: Iteso Songs of War Time Children's folklore: Kunda Songs Children's Folklore: Ndeble Classiques Africaines Color Symbolism: The Akan of Ghana Comoros Concert Parties Congo (Republic of the Congo) Contemporary Bards: Hausa Verbal Artists Cosmology Cote d'Ivoire Cote d'Ivoire, Folklore Crowley, Daniel back to top D Dance: Overview with a Focus on Namibia Decorated Vehicles (Focus on Western Nigeria) Democratic Republic of Congo Dialogic Performances: Call and Response in African Narrating Diaspora: African Communities in the United Kingdom Diaspora: African Communities in the United States Diaspora: African Traditions in Brazil Diaspora: Sea Islands of the USA Dilemma Tales Divination: Household Divination Among the Kongo Divination: Ifá Divination in Cuba Divination: Overview Djibouti Dolls and Toys Drama: Anang Ibibio Traditional Drama Draughts Dreams Dress Drumming: Ewe Dyula back to top E East African Folklore: Overview Education: Folklore in Schools Egypt Electronic Media and Oral Traditions Epics: Liongo Epic of the Swahili Epics: Overview Epics: West African Epics Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Eshu, the Yoruba Trickster Esthetics: Baule Visual Arts Ethiopia Evans-Pritchard, E. -

British Strategic Interests in the Straits of Malacca, 1786-1819

BRITISH STRATEGIC INTERESTS IN THE STRAITS OF MALACCA 1786-1819 Samuel Wee Tien Wang B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1991 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History O Samuel Wee Tien Wang 1992 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY December 1992 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Samuel Wee DEGREE: TITLE OF THESIS: British Strategic Interests in the Straits of Malacca, 1786-1819 EXAMINING COMMITTEE: CHAIR: J. I. Little ~dhardIngram, Professor Ian Dyck, Associate ~hfessor Chdrles Fedorak - (Examiner) DATE: 15 December 1992 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE 1 hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay British Strategic Interests in the Straits of Malacca Author: (signature) Samuel Wee (name) (date) ABSTRACT It has almost become a common-place assumption that the 1819 founding of Singapore at the southern tip of the strategically located Straits of Malacca represented for the English East India Company a desire to strengthen trade with China; that it was part of an optimistic and confident swing to the east which had as its goal, the lucrative tea trade. -

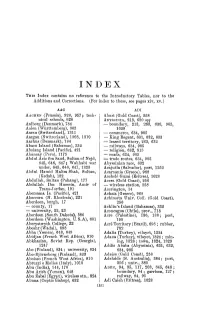

For Index to These, See Pages Xiv, Xv.)

INDEX THis Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables, nor to the Additions and Corrections. (For index to these, see pages xiv, xv.) AAC ADI AAcHEN (Prussia), 926, 957; tech- Aburi (Gold Coast), 258 nical schools, 928 ABYSSINIA, 213, 630 sqq Aalborg (Denmark), 784 - boundary, 213, 263, 630, 905, Aalen (Wiirttemberg), 965 1029 Aarau (Switzerland), 1311 - commerce, 634, 905 Aargau (Switzerland), 1308, 1310 - King Regent, 631, 632, 633 Aarhus (Denmark), 784 - leased territory, 263, 632 Abaco Island (Bahamas), 332 - railways, 634, 905 Abaiaug !Rland (Pacific), 421 - religion, 632, 815 Abancay (Peru), 1175 - roads, 634, 905 Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, Sultan of N ejd, -trade routes, 634, 905 645, 646, 647; Wahhabi war Abyssinian race, 632 under, 645, 646, 647, 1323 Acajutla (Salvador), port, 1252 Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, Sultan, Acarnania (Greece), 968 (Kedah), 182 Acchele Guzai (Eritrea), 1028 Abdullah, Sultan (Pahang), 177 Accra (Gold Coast), 256 Abdullah Ibn Hussein, Amir of - wireless station, 258 Trans-J orrlan, 191 Accrington, 14 Abemama Is. (Pacific), 421 Acha!a (Greece), 968 Abercorn (N. Rhodesia), 221 Achirnota Univ. Col!. (Gold Coast), Aberdeen, burgh, 17 256 - county, 17 Acklin's Island (Bahamas), 332 -university, 22, 23 Aconcagua (Chile), prov., 718 Aberdeen (South Dakota), 586 Acre (Palestine), 186, 188; port, Aberdeen (Washington, U.S.A), 601 190 Aberystwyth College, 22 Acre Territory (Brazil), 698 ; rubber, Abeshr (Wadai), 898 702 Abba (Yemen), 648, 649 Adalia (Turkey), vilayet, 1324 Abidjan (French West Africa), 910 Adana (Turkey), vilayet, 1324; min Abkhasian, Soviet Rep. (Georgia), ing, 1328; town, 1324, 1329 1247 Addis Ababa (Abyssinia), 631, 632, Abo (Finland), 834; university, 834 634, 905 Abo-Bjorneborg (Finland), 833 Adeiso (Gold Coast), 258 Aboisso (French West Africa), 910 Adelaide (S.