DIANA PATON & MAARIT FORDE, Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bringing Cultural Practice Into Law: Ritual and Social Norms Jurisprudence Andrew J

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 43 | Number 2 Article 2 1-1-2003 Bringing Cultural Practice Into Law: Ritual and Social Norms Jurisprudence Andrew J. Cappel Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew J. Cappel, Bringing Cultural Practice Into Law: Ritual and Social Norms Jurisprudence, 43 Santa Clara L. Rev. 389 (2003). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol43/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRINGING CULTURAL PRACTICE INTO LAW: RITUAL AND SOCIAL NORMS JURISPRUDENCE Andrew J. Cappel* I. INTRODUCTION The past decade has witnessed an explosive growth in legal scholarship dealing with the problem of informal social norms and their relationship to formal law.1 This article highlights a sa- * Associate Professor of Law, St. Thomas University Law School. J.D., Yale Law School; M.Phil., Yale University; B.A., Yale College. I would like to thank Bruce Ackerman and Stanley Fish, both of whom read prior versions of this paper, for their help and advice. I also wish to thank Robert Ellickson for his encourage- ment in this project. In addition, valuable suggestions were made by participants when a version of this paper was presented at the 2000 Law and Society conference in Miami. Among the many of my present and former colleagues at St. -

“Superstition Is the Offspring of Ignorance,” the Suppression

“SUPERSTITION IS THE OFFSPRING OF IGNORANCE,” THE SUPPRESSION OF AFRICAN SPIRITUALITY IN THE BRITISH CARIBBEAN, 1650-1834 by Carlie H. Manners Bachelor of Arts, Algoma University, 2016 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: Stefanie Hunt-Kennedy, PhD, History Gary K. Waite, PhD, History Examining Board: Lisa M. Todd, PhD, History, Chair Robert Whitney, PhD, History Elizabeth Effinger, PhD, English This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK August 2019 © Carlie H. Manners, 2019 Abstract This thesis interrogates the suppression of the enslaved spiritual practice, Obeah, through African slavery in the British Caribbean from 1650-1834. Obeah is a syncretic spiritual practice derived from West African religious epistemologies. Practitioners of Obeah invoked the spiritual world for healing, divination, and protection. What is more, under the constant threat of colonial violence, they practiced Obeah for insurrectionary purposes. This thesis reveals and contextualizes the many ways in which Obeah faced cultural suppression at the hands of religious, colonial, and imperial authorities as a means to comply with and respond to sociopolitical conflicts occurring within the British Empire. British writers conceived of Obeah as ‘ignorant’ superstition and used this against Africans as justification for their subjugation by the British empire. Furthermore, this project traces the development of the English concern for Obeah alongside their pre- existing conceptions of magic and religion, which influenced the ways in which British colonists confronted African practitioners. ii Dedication For my grandparents, Claus and Linda. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:10:37AM Via Free Access 2 Pires, Strange and Mello Several Afro- and Indo-Guianese Populations

New West Indian Guide 92 (2018) 1–34 nwig brill.com/nwig The Bakru Speaks Money-Making Demons and Racial Stereotypes in Guyana and Suriname* Rogério Brittes W. Pires Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil [email protected] Stuart Earle Strange Yale-NUS College, Singapore [email protected] Marcelo Moura Mello Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Brazil [email protected] Abstract Throughout the Guianas, people of all ethnicities fear one particular kind of demonic spirit. Called baccoo in Guyana, bakru in coastal Suriname, and bakulu or bakuu among Saamaka and Ndyuka Maroons in the interior, these demons offer personal wealth in exchange for human life. Based on multisited ethnography in Guyana and Suriname, this paper analyzes converging and diverging conceptions of the “same” spirit among * Most of the research for this article was carried out by the authors during fieldwork for their Ph.D. dissertation.The research was financed byThe National Science Foundation,The Social Science Research Council, The Wenner Gren Foundation, and the University of Michigan’s Department of Anthropology (Stuart Strange); by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Museu Nacional’s Graduate Program in Social Anthro- pology, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (ufrj) (Marcelo Mello and Rogério Pires); and by a CNPq postdoctoral scholarship in the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Rogério Pires). Previous versions of this article were presented twice in 2015 and once in 2017: in a seminar at Museu Nacional/ufrj, in a panel session at the American Anthropological Asso- ciation (aaa) meeting, and in a lecture at Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (ufjf). -

AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Open Educational Resources Borough of Manhattan Community College 2021 AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture Remi Alapo CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bm_oers/29 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Presented as part of the discussion on West Africa about the instructor’s Heritage in the AFN 121 course History of African Civilizations on April 20, 2021. Yoruba Tradition and Culture Prof. Remi Alapo Department of Ethnic and Race Studies Borough of Manhattan Community College [BMCC]. Questions / Comments: [email protected] AFN 121 - History of African Civilizations (Same as HIS 121) Description This course examines African "civilizations" from early antiquity to the decline of the West African Empire of Songhay. Through readings, lectures, discussions and videos, students will be introduced to the major themes and patterns that characterize the various African settlements, states, and empires of antiquity to the close of the seventeenth century. The course explores the wide range of social and cultural as well as technological and economic change in Africa, and interweaves African agricultural, social, political, cultural, technological, and economic history in relation to developments in the rest of the world, in addition to analyzing factors that influenced daily life such as the lens of ecology, food production, disease, social organization and relationships, culture and spiritual practice. -

The Bogeyman Show Notes Season 1, Episode 6

The Bogeyman Show Notes Season 1, Episode 6 Welcome to episode six of the Time Pieces History Podcast. I can’t believe we’re halfway through the first season already! I decided we’d have some light relief today, and look at the legend of the bogeyman. This creature pops up around the world, not just in Britain, but he’s certainly significant. As part of my Time Pieces History Project I looked at some of my favourite books, so this episode is inspired by that, and in particular Raymond Briggs’ Fungus the Bogeyman, a family man who has questions about his life. If you haven’t read Fungus, I highly recommend getting yourself a copy. Briggs is probably more famous for his books The Snowman and Father Christmas, but I always preferred Fungus, perhaps because of Briggs’ lovingly-drawn illustrations of his underground world. It’s also full of puns and funny inventions, which made me laugh rereading it as an adult. Bogeymen like things damp and mouldy, and keep their clothes in a ‘waterobe.’ In private they’re polite and softly-spoken, and like to go to art galleries, where they get emotional over the paintings. Fungus’ day job though (or should that be night job?) is the more traditional bogeyman role, of scaring children, disturbing people’s sleep and turning milk sour. Over several pages, we see Fungus wondering if there should be more to his existence than traumatising humans, in scenes which are both hilarious and sad. Raymond Briggs put his own spin on the legend of the bogeyman, which is fine, because one good thing about them is that there’s no hard and fast rule on what one looks like, or what they do. -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

Scholarship 2004–2005

SCHOLARSHIP 2004–2005 The 2004–2005 edition of the Duquesne University Scholarship bibliography was produced at the Gumberg Library, under the direction of Laverna Saunders, University Librarian. The bibliography was compiled by Matthew Boyer, Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Coordinator. Editorial assistance was provided by Leslie Lewis, Barbara Adams, and Allison Brungard. Duquesne University 600 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15282 http://www.duq.edu © 2006 CONTENTS Letter from the President....................................................................................................................v Publications...........................................................................................................................................1 McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts ........................................................3 Bayer School of Natural and Environmental Sciences..........................................................16 School of Law..............................................................................................................................23 A. J. Palumbo School of Business Administration and John F. Donahue Graduate School of Business ......................................................................................................................25 Mylan School of Pharmacy........................................................................................................29 Mary Pappert School of Music..................................................................................................32 -

The Spiritual Landscapes of Barbados

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2016 Sacred Grounds and Profane Plantations: The Spiritual Landscapes of Barbados Myles Sullivan College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the African History Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Cultural History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Sullivan, Myles, "Sacred Grounds and Profane Plantations: The Spiritual Landscapes of Barbados" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 945. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/945 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sullivan 1 Sacred Grounds and Profane Plantations: The Spiritual Landscapes of Barbados Myles Sullivan Sullivan 2 Table of Contents Introduction page 3 Background page 4 Research page 6 Spiritual Landscapes page 9 The Archaeology and Anthropology of Spiritual Practices in the Caribbean page 16 Early Spiritual Landscapes page 21 Barbadian Spiritual Landscapes: Liminal Spaces in a “Creole” Slave Society page 33 Spiritual Landscapes of Recent Memory page 47 Works Cited page 52 Figures Fig 1: Map of Barbados page 4 Fig 2: Worker’s Village Site at Saint Nicholas Abbey page 7 Fig 3: Stone pile on ridgeline page 8 Fig 4: Disembarked Africans on Barbados (1625-1850) page 23 Fig 5: Total percentage arrivals of Africans by regions page 23 Fig 6: “Gaming” Pieces from the slave village site page 42 Fig 7: Gully areas at St. -

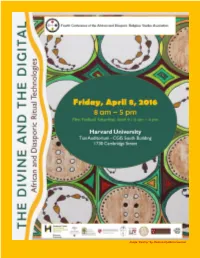

2016 Conference Program

Image “Destiny” by Deanna Oyafemi Lowman MOYO ~ BIENVENIDOS ~ E KAABO ~ AKWABAA BYENVENI ~ BEM VINDOS ~ WELCOME Welcome to the fourth conference of the African and Diasporic Religious Studies Association! ADRSA was conceived during a forum of scholars and scholar- practitioners of African and Diasporic religions held at the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School in October 2011 and the idea was solidified during the highly successful Sacred Healing and Wholeness in Africa and the Americas symposium held at Harvard in April 2012. Those present at the forum and the symposium agreed that, as with the other fields with which many of us are affiliated, the expansion of the discipline would be aided by the formation of an association that allows researchers to come together to forge relationships, share their work, and contribute to the growing body of scholarship on these rich traditions. We are proud to be the first US-based association dedicated exclusively to the study of African and Diasporic Religions and we look forward to continuing to build our network throughout the country and the world. Although there has been definite improvement, Indigenous Religions of all varieties are still sorely underrepresented in the academic realms of Religious and Theological Studies. As a scholar- practitioner of such a tradition, I am eager to see that change. As of 2005, there were at least 400 million people practicing Indigenous Religions worldwide, making them the 5th most commonly practiced class of religions. Taken alone, practitioners of African and African Diasporic religions comprise the 8th largest religious grouping in the world, with approximately 100 million practitioners, and the number continues to grow. -

Hebi Sani: Mental Well Being Among the Working Class Afro-Surinamese in Paramaribo, Suriname

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME Aminata Cairo University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cairo, Aminata, "HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME" (2007). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 490. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/490 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aminata Cairo The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME ____________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aminata Cairo Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Deborah L. Crooks, Professor of Anthropology Lexington, Kentucky 2007 Copyright © Aminata Cairo 2007 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE -

ANTI-AMERICANISMS in FRANCE Sophie Meunier

07-Meunier 5/26/05 3:39 PM Page 125 ANTI-AMERICANISMS IN FRANCE Sophie Meunier Princeton University France is undoubtedly the first response that comes to mind when asked which country in Europe is the most anti-American. Between taking the lead of the anti-globalization movement in the late 1990s and taking the lead of the anti-war in Iraq camp in 2003, France confirmed its image as the “oldest enemy” among America’s friends.1 Even before the days of De Gaulle and Chirac, it seems that France has always been at the forefront of anti-American animosity—whether through eighteenth-century theories about the degener- ation of species in the New World or through 1950s denunciations of the Coca-Colonization of the Old World.2 The American public certainly returns the favor, from pouring French wine onto the street to renaming fries and toast, and France has become the favorite bogeyman of conservative shows and provided material for countless late-night comedians’ jokes.3 Surprisingly, however, polling data reveals that France is not drastically more anti-American than other European countries—even less so on a variety of dimensions. The French do stand out in their criticism of US unilateral leadership in world affairs and in their willingness to build an independent Europe able to compete with the United States if needed.4 But their overall feelings towards the US were not dramatically different from those of other European countries in 2004.5 Neither was their assessment of the primary motives driving American foreign policy, and US Middle East policy in partic- ular.6 Furthermore, despite what seems like growing gaps in their societal val- ues (especially regarding religion), French and American public opinions agree on the big threats facing their societies, and they still share enough values to cooperate on international problems. -

PHD DISSERTATION Shanti Zaid Edit

“A DOG HAS FOUR LEGS BUT WALKS IN ONE DIRECTION:” MULTIPLE RELIGIOUS BELONGING AND ORGANIC AFRICA-INSPIRED RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS IN ORIENTE CUBA By Shanti Ali Zaid A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of African American and African Studies—Doctor of Philosophy Anthropology—Dual Major 2019 ABSTRACT “A DOG HAS FOUR LEGS BUT WALKS IN ONE DIRECTION:” MULTIPLE RELIGIOUS BELONGING AND ORGANIC AFRICA-INSPIRED RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS IN ORIENTE CUBA By Shanti Ali Zaid If religion is about social cohesion and the coordination of meaning, values, and motivations of a community or society, hoW do communities meaningfully navigate the religious domain in an environment of multiple religious possibilities? Within the range of socio-cultural responses to such conditions, this dissertation empirically explores “multiple religious belonging,” a concept referring to individuals or groups Whose religious identity, commitments, or activities may extend beyond a single coherent religious tradition. The project evaluates expressions of this phenomenon in the eastern Cuban city of Santiago de Cuba With focused attention on practitioners of Regla Ocha/Ifá, Palo Monte, Espiritismo Cruzado, and Muertería, four organic religious traditions historically evolved from the efforts of African descendants on the island. With concern for identifying patterns, limits, and variety of expression of multiple religious belonging, I employed qualitative research methods to explore hoW distinctions and relationships between religious traditions are articulated, navigated, and practiced. These methods included directed formal and informal personal intervieWs and participant observations of ritual spaces, events, and community gatherings in the four traditions. I demonstrate that religious practitioners in Santiago manage diverse religious options through multiple religious belonging and that practitioners have strategies for expressing their multiple religious belonging.