Hebi Sani: Mental Well Being Among the Working Class Afro-Surinamese in Paramaribo, Suriname

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Practices and Linguistic Ideologies in Suriname: Results from a School Survey

CHAPTER 2 Language Practices and Linguistic Ideologies in Suriname: Results from a School Survey Isabelle Léglise and Bettina Migge 1 Introduction The population of the Guiana plateau is characterised by multilingualism and the Republic of Suriname is no exception to this. Apart from the country’s official language, Dutch, and the national lingua franca, Sranantongo, more than twenty other languages belonging to several distinct language families are spoken by less than half a million people. Some of these languages such as Saamaka and Sarnámi have quite significant speaker communities while others like Mawayana currently have less than ten speakers.1 While many of the languages currently spoken in Suriname have been part of the Surinamese linguistic landscape for a long time, others came to Suriname as part of more recent patterns of mobility. Languages with a long history in Suriname are the Amerindian languages Lokono (Arawak), Kari’na, Trio, and Wayana, the cre- ole languages Saamaka, Ndyuka, Matawai, Pamaka, Kwinti, and Sranantongo, and the Asian-Surinamese languages Sarnámi, Javanese, and Hakka Chinese. In recent years, languages spoken in other countries in the region such as Brazilian Portuguese, Guyanese English, Guyanese Creole, Spanish, French, Haitian Creole (see Laëthier this volume) and from further afield such as varieties of five Chinese dialect groups (Northern Chinese, Wu, Min, Yue, and Kejia, see Tjon Sie Fat this volume) have been added to Suriname’s linguistic landscape due to their speakers’ increasing involvement in Suriname. Suriname’s linguistic diversity is little appreciated locally. Since indepen- dence in 1975, successive governments have pursued a policy of linguistic assimilation to Dutch with the result that nowadays, “[a] large proportion of the population not only speaks Dutch, but speaks it as their first and best language” (St-Hilaire 2001: 1012). -

4. Remaining Anonymous

VIVIAN WENLI LIN 4. REMAINING ANONYMOUS Using Participatory Arts-Based Methods with Migrant Women Workers in the Age of the Smartphone OBJECTIVES Background: Voices of Women Media Communities of Turkish, Moroccan, Surinamese, Indonesian, and Chinese immigrants who are considered, officially, allochtoon—born in another country or having a parent from another country—have long settled in the Netherlands. Pooja Pant, a Nepalese media activist, and I were curious about their experience of becoming Dutch since we had both just arrived to live and work in Amsterdam so we co-founded Voices of Women (VOW) Media in 2007 and we partnered with various community-based organizations working in the area of migrant women’s rights1 to run participatory media workshops. In 2012, we decided to expand this work to East Asia and South Asia out of a personal desire to establish connections to the countries of our parents. Through these partnerships and over the following nine years we worked closely with women sex workers who see themselves as being invisible in society as a whole but visible to the public. In their lacking opportunity and access to resources, they are often discussed by those in power who make decisions, such as politicians, the media, or policy makers, but are not included in the discussion. To use the words of Srilatha Batliwala, in this work VOW Media explores women’s empowerment as part of “both a process and the result of that process” (1994, p. 130). In a collaborative and non-hierarchical setting we engage with communities of migrant women using participatory arts-based methodologies, including cellphilms, in order to create audiovisual media works that highlight their life stories. -

Key Data on Migrant Presence and Integration in Amsterdam 21 │

KEY DATA ON MIGRANT PRESENCE AND INTEGRATION IN AMSTERDAM 21 │ Key data on migrant presence and integration in Amsterdam Figure 0.1. Amsterdam’s geographic location in the Netherlands according to the OECD regional classification Source: OECD (2018), OECD Regional Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en. Municipality TL3 TL2 State Amsterdam Groot-Amsterdam Noord-Holland Netherlands Greater Amsterdam Note: TL2: Territorial Level 2 consists of the OECD classification of regions within each member country. There are 335 regions classified at this level across 35 member countries TL3: Territorial Level 3 consists of the lower level of classification and is composed of 1681 small regions. In most of the cases they correspond to administrative regions. This section presents key definitions and a selection of indicators about migrants presence and results in Amsterdam. WORKING TOGETHER FOR LOCAL INTEGRATION OF MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES IN AMSTERDAM © OECD 2018 22 KEY DATA ON MIGRANT PRESENCE AND INTEGRATION IN AMSTERDAM │ Definition of migrant and refugee The term ‘migrant’ generally functions as an umbrella term used to describe people that move to another country with the intention of staying for a significant period of time. According to the United Nations (UN), a long-term migrant is “a person who moves to a country other than that of his or her usual residence for a period of at least a year (12 months)”. Yet, not all migrants move for the same reasons, have the same needs or come under the same laws. This report considers migrants as a large group that includes: • those who have emigrated to an EU country from another EU country (‘EU migrants’) • those who have come to an EU country from a non-EU country (‘non-EU born or third-country national’) • native-born children of immigrants (often referred to as the ‘second generation’) • persons who have fled their country of origin and are seeking international protection. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

DIANA PATON & MAARIT FORDE, Editors

diana paton & maarit forde, editors ObeahThe Politics of Caribbean and Religion and Healing Other Powers Obeah and Other Powers The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing diana paton & maarit forde, editors duke university press durham & london 2012 ∫ 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Katy Clove Typeset in Arno Pro by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Newcastle University, which provided funds toward the production of this book. Foreword erna brodber One afternoon when I was six and in standard 2, sitting quietly while the teacher, Mr. Grant, wrote our assignment on the blackboard, I heard a girl scream as if she were frightened. Mr. Grant must have heard it, too, for he turned as if to see whether that frightened scream had come from one of us, his charges. My classmates looked at me. Which wasn’t strange: I had a reputation for knowing the answer. They must have thought I would know about the scream. As it happened, all I could think about was how strange, just at the time when I needed it, the girl had screamed. I had been swimming through the clouds, unwillingly connected to a small party of adults who were purposefully going somewhere, a destination I sud- denly sensed meant danger for me. Naturally I didn’t want to go any further with them, but I didn’t know how to communicate this to adults and ones intent on doing me harm. -

The Netherlands from National Identity to Plural Identifications

The NeTherlaNds From NaTioNal ideNTiTy To Plural ideNTiFicaTioNs By Monique Kremer TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION THE NETHERLANDS From National Identity to Plural Identifications Monique Kremer March 2013 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), for its seventh plenary meeting, held November 2011 in Berlin. The meeting’s theme was “National Identity, Immigration, and Social Cohesion: (Re)building Community in an Ever-Globalizing World” and this paper was one of the reports that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council, an MPI initiative undertaken in cooperation with its policy partner the Bertelsmann Stiftung, is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: Carnegie Corporation of New York, Open Society Foundations, Bertelsmann Stiftung, the Barrow Cadbury Trust (UK Policy Partner), the Luso-American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/transatlantic. © 2013 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: Danielle Tinker, MPI Typesetting: April Siruno and Rebecca Kilberg, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and re- trieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from: www.migrationpolicy.org. Information for reproducing excerpts from this report can be found at www.migrationpolicy.org/about/copy.php. -

An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation

Global Media Journal German Edition From the field An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation Andrej Školkay1 Abstract: This is a study of suggested approaches to social media regulation based on an explora- tory methodological approach. Its first aim is to provide an overview of the global and local debates and the main arguments and concerns, and second, to systematise this in order to construct taxon- omies. Despite its methodological limitations, the study provides new insights into this very rele- vant global and local policy debate. We found that there are trends in regulatory policymaking to- wards both innovative and radical approaches but also towards approaches of copying broadcast media regulation to the sphere of social media. In contrast, traditional self- and co-regulatory ap- proaches seem to have been, by and large, abandoned as the preferred regulatory approaches. The study discusses these regulatory approaches as presented in global and selected local, mostly Euro- pean and US discourses in three analytical groups based on the intensity of suggested regulatory intervention. Keywords: social media, regulation, hate speech, fake news, EU, USA, media policy, platforms Author information: Dr. Andrej Školkay is director of research at the School of Communication and Media, Bratislava, Slovakia. He has published widely on media and politics, especially on political communication, but also on ethics, media regulation, populism, and media law in Slovakia and abroad. His most recent book is Media Law in Slovakia (Kluwer Publishers, 2016). Dr. Školkay has been a leader of national research teams in the H2020 Projects COMPACT (CSA - 2017-2020), DEMOS (RIA - 2018-2021), FP7 Projects MEDIADEM (2010-2013) and ANTICORRP (2013-2017), as well as Media Plurality Monitor (2015). -

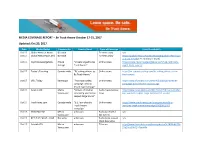

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017 Date Media Outlet Community Header/Lead Type of Coverage Link (if available) Oct 17 Global News at Noon BC-wide TV news story n/a Oct 17 Global News Hours at 6 BC-wide TV news story https://globalnews.ca/video/3810220/global-news-hour- at-6-oct-17-4 (at 21:14 minute mark) Oct 17 MyPrinceGeorgeNow Prince “Drivers Urged to Be Online news https://www.myprincegeorgenow.com/59471/drivers- George Truck Aware” urged-truck-aware/ Oct 17 Today’s Trucking Canada-wide “BC asking drivers to Online news https://m.todaystrucking.com/bc-asking-drivers-to-be- Be Truck Aware” truck-aware Oct 17 CFJC Today Kamloops “Provincial safety Online news http://www.cfjctoday.com/article/592118/provincial- campaign aims to campaign-aims-lessen-road-carnage lessen road carnage” Oct 17 News 1130 Metro “Drivers of smaller Radio News/online http://www.news1130.com/2017/10/17/drivers-smaller- Vancouver cars being warned to news cars-warned-respect-large-commercial-trucks/ respect large trucks” Oct 17 TruckNews.com Canada-wide “B.C. launches Be Online news https://www.trucknews.com/transportation/b-c- Truck Aware launches-truck-aware-campaign/1003081520/ campaign” Oct 17 CKYE RED FM Metro unknown Radio (attended n/a Vancouver the event) Oct 17 97.3 THE EAGLE - CKLR Nanaimo unknown Radio (interviewed n/a Mark Donnelly) Oct 17 Fairchild TV Metro unknown TV news http://www.fairchildtv.com/news.php?n=5c2868adb73b Vancouver 23a26ca29b7244babfdb Oct 17 Kamloopscity.com Kamloops “Drivers urged to -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

Columbia University Press

r Columbia University Press •Publishers Since 1893 BETWEEN MEN - BETWEEN WOMEN New York Chichester, West Sussex Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Studies Copyright © 2006 Columbia University Press Terry Castle and Larry Gross, Editors All rights reserved The publication of this book was made possible by a grant from the Advisory Board of Editors Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). Claudia Card John D'Emilio Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wekker, Gloria. Esther Newton The politics of passion : women's sexual culture in the Afro-Surinamese diaspora Anne Peplau Gloria Wekker. Eugene Rice em. - (Between men-between women) p. Kendal! Thomas Revision of the author's thesis published in 1994 under title: Ik ben een gouden munt, ik ga door vele han den, maar ik verlies mijn waarde niet. Jeffrey Weeks Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN o-231-13162-3 (cloth: alk. paper)- ISBN 0-231-13163-1 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Women-Suriname-Paramaribo-Sexual behavior. 2. Women-Suriname Paramaribo-Identity. 3. Sex customs-Suriname-Paramaribo. 4. Lesbianism-Suriname Paramaribo. 5. Creoles-Suriname-Paramaribo. I. Wekker, Gloria. Ik ben een gouden munt, BETWEEN MEN - BETWEEN WOMEN is a forum for current lesbian and gay ik ga door vele han den, maar ik verlies mijn waarde niet. II. Title. III. Series. scholarship in the humanities and social sciences. The series includes both HQ29.W476 2006 306.76'5o8996o883-dc22 books that rest within specific traditional disciplines and are substantially about 2005054320 gay men, bisexuals, or lesbians and books that are interdisciplinary in ways that Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and reveal new insights into gay, bisexual, or lesbian experience, transform tradi durable acid-free paper. -

Ethnic Diversity and Social Stratification in Suriname in 2012

ETHNIC DIVERSITY AND SOCIAL STRATIFICATION IN SURINAME IN 2012 Tamira Sno, Harry BG Ganzeboom and John Schuster No matter how we came together here, we are pledged to this ground (National Anthem Suriname) Abstract This paper examines the relative socio-economic positions of ethnic groups in Suriname. Our results are based on data from the nationally representative survey Status attainment and Social Mobility in Suriname 2011-2013 (N=3929). The respondents are divided into eight groups on the basis of self-identification: Natives, Maroons, Hindustanis, Javanese, Creoles, Chinese, Mixed and Others (mainly immigrants). We measure the socio-economic positions of the ethnic groups based on education and occupation and assess historical changes using cohort, intergenerational and lifecycle comparisons. The data allow us to create an ethnic hierarchy based on the social-economic criteria that we have used. We show that Hindustanis, Javanese and Creoles are ranked in the middle of the social stratification system of Suriname, but that Creoles have rather more favourable positions than the other two groups. Natives and Maroons are positioned at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder, and together – with almost 20% of the population - they form a sizeable lower class, also, and in increasing numbers in urban areas. At the top of the Surinamese social ladder, we find a large group of Mixed, together with the small groups of Chinese and Others. The rank order in the stratification system is historically stable. Still, there are also clear signs of convergence between the ethnic groups, in particular, when we compare the generations of respondents with their parents. -

African Power West African Mediums Catering to Surinamese Clients in the Netherlands

African Diaspora 9 (2016) 39–60 brill.com/afdi African Power West African Mediums Catering to Surinamese Clients in the Netherlands Amber Gemmeke* University of Bayreuth, Germany [email protected] Abstract This paper explores how West African migrants’ movements impacts their religious imagery and that of those they encounter in the diaspora. It specifically addresses how, through the circulation of objects, rituals, and themselves, West Africans and Black Dutchmen of Surinamese descent link, in a Dutch urban setting, spiritual empower- ing and protection to the African soil. West African ‘mediums’ offer services such as divination and amulet making since about twenty years in the Netherlands. Dutch- Surinamese clients form a large part of their clientele, soliciting a connection to Afri- can, ancestral spiritual power, a power which West African mediums enforce through the use of herbs imported from West Africa and by rituals, such as animal sacrifices and libations, arranged for in West Africa. This paper explores how West Africans and Dutchmen of Surinamese descent, through a remarkable mix of repertoires alluding to notions of Africa, Sufi Islam, Winti, and Western divination, creatively reinvent a shared understanding of ‘African power’. Keywords Black Caribbeans – Sufi Islam – Winti – marabout – diaspora – ritual * I thank Prof. dr. Tinde van Andel, Dr. Karel Arnaut, Dr. Linda van de Kamp and two anony- mous reviewers for their valuable suggestions for this article. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2017 | doi: 10.1163/18725465-00901004 Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 09:33:46PM via free access 40 gemmeke Résumé Cette contribution explore l’impact des mouvements migratoires des Africains occi- dentaux sur leur imagerie religieux et celui de ceux qu’ils rencontrent dans la diaspora.