An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

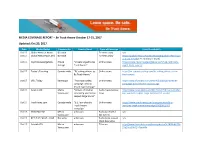

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017 Date Media Outlet Community Header/Lead Type of Coverage Link (if available) Oct 17 Global News at Noon BC-wide TV news story n/a Oct 17 Global News Hours at 6 BC-wide TV news story https://globalnews.ca/video/3810220/global-news-hour- at-6-oct-17-4 (at 21:14 minute mark) Oct 17 MyPrinceGeorgeNow Prince “Drivers Urged to Be Online news https://www.myprincegeorgenow.com/59471/drivers- George Truck Aware” urged-truck-aware/ Oct 17 Today’s Trucking Canada-wide “BC asking drivers to Online news https://m.todaystrucking.com/bc-asking-drivers-to-be- Be Truck Aware” truck-aware Oct 17 CFJC Today Kamloops “Provincial safety Online news http://www.cfjctoday.com/article/592118/provincial- campaign aims to campaign-aims-lessen-road-carnage lessen road carnage” Oct 17 News 1130 Metro “Drivers of smaller Radio News/online http://www.news1130.com/2017/10/17/drivers-smaller- Vancouver cars being warned to news cars-warned-respect-large-commercial-trucks/ respect large trucks” Oct 17 TruckNews.com Canada-wide “B.C. launches Be Online news https://www.trucknews.com/transportation/b-c- Truck Aware launches-truck-aware-campaign/1003081520/ campaign” Oct 17 CKYE RED FM Metro unknown Radio (attended n/a Vancouver the event) Oct 17 97.3 THE EAGLE - CKLR Nanaimo unknown Radio (interviewed n/a Mark Donnelly) Oct 17 Fairchild TV Metro unknown TV news http://www.fairchildtv.com/news.php?n=5c2868adb73b Vancouver 23a26ca29b7244babfdb Oct 17 Kamloopscity.com Kamloops “Drivers urged to -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

Hebi Sani: Mental Well Being Among the Working Class Afro-Surinamese in Paramaribo, Suriname

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME Aminata Cairo University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cairo, Aminata, "HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME" (2007). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 490. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/490 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aminata Cairo The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME ____________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aminata Cairo Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Deborah L. Crooks, Professor of Anthropology Lexington, Kentucky 2007 Copyright © Aminata Cairo 2007 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE -

Optik TV Channel Listing Guide 2020

Optik TV ® Channel Guide Essentials Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver/ Kelowna/ Prince Dawson Victoria/ Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel Cranbrook McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 Alberta Assembly TV ABLEG 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● AMI-audio* AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé* AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv* AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West)* ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 — APTN HD* APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 — BC Legislative TV* BCLEG — — — — — — — — 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 CBC Calgary* CBRTDT ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC Edmonton* CBXTDT 100 100 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC News Network CBNEWHD 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 CBC Vancouver* CBUTDT ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 CBS Seattle KIRODT 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 CHEK* CHEKDT — — — — — — — — 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 Citytv Calgary* CKALDT ● ● ● ● ● 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Edmonton* CKEMDT 106 106 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Vancouver* -

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends First Quarter, 2015 Q1 highlights: effective and efficient policy research & outreach Q1 research 14 research papers 3 Verbatims 2 Monetary Policy Council releases Q1 policy events 11 policy events and special meetings, including: Montreal Roundtable – Sophie Brochu, President and CEO, Gaz Métro Ottawa Roundtable - Lt. Gen. Charles Bouchard, Country Leader, Lockheed Martin Canada Toronto Roundtable – Mitzie Hunter, Associate Minister of Finance, Ontario Calgary Roundtable – Ian Telfer, Chairman of the Board, Goldcorp Policy Outreach in Q1 109,032 website pageviews 12 policy outreach presentations 34 National Post and Globe and Mail citations Citations in more than 80 media outlets 36 media interviews 20 opinion and editorial pieces 2 Q1 select policy influence Health papers receive national recognition including acknowledgements by senior government officials Nova Scotia’s Health Minister acknowledged the province’s looming fiscal burden while responding to an Institute paper and the Federal Leader of Liberal Party cited the Institute’s recent vaccination study. Reports: Delivering Healthcare to an Aging Population: Nova Scotia’s Fiscal Glacier and A Shot in the Arm: How to Improve Vaccination Policy in Canada Op-Eds: New Brunswick’s demographic challenge: Telegraph- Journal Op-Ed and Booster shot for Ontario’s vaccination policies: Toronto Star Op-Ed Alberta budget is presented on a fully consolidated basis in a format supported by the Auditor General Alberta Finance Minister acknowledged that more clarity is needed in budget presentation after the Institute gave the province a C grade. Report: Credibility on the (Bottom) Line: The Fiscal Accountability of Canada’s Senior Governments, 2013 Op-Eds: A decade of government overspending has left us over-taxed and deeper in debt: Globe and Mail Op- Ed, Saskatchewan budget – Adding up the numbers: Leader-Post Op-Ed Canada and U.S. -

Minutes from City Commission Minutes From

DUNEDIN, FLORIDA MINUTES OF THE CITY COMMISSION WORK SESSION MARCH 17, 2020 9:00A.M. -12:30 P.M. Present: City Commission: Mayor Julie Ward Bujalsk1, V1ce-Mayor Heather Gracy, Commissioners, Deborah Kynes and Jeff Gow Commissioner Maureen "Moe" Freaney (Via Conference Call) Also Present. City Manager Jennifer K Bramley, Deputy C1ty Manager Doug Hutchens, City Attorney Thomas J. Trask, City Clerk Rebecca Schlichter, Finance Director Les Tyler, Commumty Development Planner II Frances Sharp, Economic & Housing Development!CRA Director Robert lronsm1th, Assistant D1rector of Public Works & Utilities Paul Stanek, Community Relations .TV Production Specialist Just1n Catacchio, Information Technology Services Division D1rector Michael Nagy, Parks and Recreation Director Vince Gizzi, Parks & Recreation Administration Supenntendent Lame Sheets, Community Center Program Coordinator Jorie Peterson, Fire Chief Jeffrey Parks, Deputy Fire Chief Erich Thiemann, Fire Marshal M1ke Handoga, Library Director Phyllis Gorshe and approximately five people. CALL TO ORDER 1 Mayor Bujalski called the Work Session to order at 9:00 a.m. City Attorney Trask explained for any action to take place at the Commission level 1t requ1res all meetings to be held in the Sunshine. It is his understanding Commissioner Freaney has recently been on a cruise and has self-quarantined as a d1rect result of the Coronavirus pandemic and the emergency it creates, she is attending this Commission Meeting by way of aud1o. The Attorney General has opmed on th1s m 1992 that so long as there is a quorum physically present at the meeting and so long as an emergency exists a Commissioner can attend the meeting and part1c1pate m the meeting by phone. -

Image and Self-Representation

Veszelszki, Ágnes (ELTE) Image and Self-representation Giving people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.1 1. Introduction The involvement of image information is commonly said to be an accessory of digital change (see: Schlobinski 2009: 6). Visuality has a much more important role in our days than it had in the earlier periods of communication history. Just have a look at the graphical user interface of computer programmes, the layout of web pages, texts full of smileys and the torrent of pictures shared on social networking pages. This paradigm shift in the wake of the Gutenberg Galaxy is termed by Gottfried Boehm as the “Iconic Turn” (Boehm 1994). With the spread of visual communication technologies, visual communication itself is getting more and more common, too (Nyíri 2003: 273). In fact, some speak about the omnipresence of pictures (“Omnipräsenz der Bilder”; Maar 2006). Images are not under the control of consciousness, they bypass our minds and influence our thinking and emotions through their suggestive power (Giulani 2006: 185). Profile pictures on social networking websites fall into a peculiar category. It’s an open secret that our photos uploaded to such websites are not only viewed by our friends and family members but also by our present or future employer. A British survey, which was carried out by the People Search website, polled almost one thousand HR managers asking them if they inspected their employee-to-be’s photos shared on the internet before contracting them. One third of the British managers said that they regularly viewed their colleagues’ photos and internet posts, and they found this method of gathering information quite important before hiring a new employee. -

BOARD of GOVERNORS Monday, March 30, 2015 Jorgenson Hall – JOR 1410 380 Victoria Street 5:00 P.M

BOARD OF GOVERNORS Monday, March 30, 2015 Jorgenson Hall – JOR 1410 380 Victoria Street 5:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. AGENDA TIME ITEM PRESENTER ACTION Page 5:00 1. IN-CAMERA DISCUSSION (Board Members Only) 5:05 2. IN-CAMERA DISCUSSION (Senior Management Invited) END OF IN-CAMERA SESSION 5:35 6. INTRODUCTION 6.1 Chair’s Remarks Janice Fukakusa Information 6.2 Approval of the March 30, 2015 Agenda Janice Fukakusa Approval 5:40 7. PRESIDENT’S REPORT Sheldon Levy Information 48-54 7.1 Enactus Presentation Stefany Nieto and Information 55-80 Benjamin Canning, Enactus 7.2 Toronto is Basketball Information i. Canadian Intramural Sports (CIS) Heather Lane Vetere ii. Pan Am Games Erin McGinn 5:55 8. SECRETARY’S REPORT 8.1 Board Election Report Update Julia Shin Doi Information 81-87 6:00 9. REPORT FROM THE PROVOST AND VICE Mohamed Lachemi Information 88-94 PRESIDENT ACADEMIC 9.1 Academic Administrative Appointment Mohamed Lachemi Information 95 9.2 Referendum Request from the Ryerson Science Mohamed Lachemi Approval 96-108 Society Heather Lane Vetere Ana Sofia Vargas- Garza Adrian Popescu 6:20 10. REPORT FROM THE CHAIR OF THE FINANCE Mitch Frazer Information COMMITTEE 10.1 Ryerson Student Union Fees Presentation Jesse Root, Vice Information 109-116 President, Education RSU 6:35 10.2 Budget 2015-16: Part One – Environmental Scan Mohamed Lachemi Information 117-134 Paul Stenton 10.3 Budget 2015-16: Part Two - Fees Context Paul Stenton Information 135-170 11. CONSENT AGENDA 11.1 Approval of the Minutes of January 26, 2015 and Janice Fukakusa Approval 171-174 the Minutes of the March 5, 2015 Special Meeting of the Board 11.2 Third Quarter Financial Results Janice Winton Approval 175-182 11.3 Review of Revenue and Expenditures for New Paul Stenton Approval 183-189 Bachelor of Arts in Language and Intercultural Relations 11.4 Review of revenue and expenditures for new Paul Stenton Approval 190 Professional Masters Diploma in Energy and Innovation 11.5 Fiera Capital Report December 31, 2014 Janice Winton Information 191-211 12. -

Geographies of an Online Social Network

Geographies of an online social network Balázs Lengyel a,b, 1, Attila Varga c, Bence Ságvári a,d, Ákos Jakobi e, János Kertész f,g a International Business School Budapest, OSON Research Lab, Záhony utca 7, 1031 Budapest, Hungary b Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Budaörsi út 45, 1112 Budapest, Hungary c The University of Arizona, School of Sociology, Tucson, AZ 85721-0027, USA d Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Centre for Social Sciences, Országház utca 30, 1014 Budapest, Hungary e Eötvös Loránd University, Department of Regional Science; Pázmány Péter sétány 1/C, 1117 Budapest, Hungary f Central European University, Centre for Network Science, Nádor utca 9, 1051 Budapest, Hungary g Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Institute of Physics, Budafoki út 8, 1111 Budapest, Hungary 1 Corresponding author: [email protected]. 1 Geographies of an online social network Abstract How is online social media activity structured in the geographical space? Recent studies have shown that in spite of earlier visions about the “death of distance”, physical proximity is still a major factor in social tie formation and maintenance in virtual social networks. Yet, it is unclear, what are the characteristics of the distance dependence in online social networks. In order to explore this issue the complete network of the former major Hungarian online social network is analyzed. We find that the distance dependence is weaker for the online social network ties than what was found earlier for phone communication networks. For a further analysis we introduced a coarser granularity: We identified the settlements with the nodes of a network and assigned two kinds of weights to the links between them. -

Ethnology of the Blackfeet. INSTITUTION Browning School District 9, Mont

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 060 971 RC 005 944 AUTHOR McLaughlin, G. R., Comp. TITLE Ethnology of the Blackfeet. INSTITUTION Browning School DiStrict 9, Mont. PUB DATE [7 NOTE 341p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$13-16 DESCRIPTORS *American Indians; Anthologies; Anthropology; *Cultural Background; *Ethnic Studies; Ethnolcg ; *High School Students; History; *Instructional Materials; Mythology; Religion; Reservations (Indian); Sociology; Values IDENTIFIERS *Blackfeet ABSTRACT Compiled for use in Indian history courses at the high-school level, this document contains sections on thehistory, culture, religion, and myths and legends of theBlackfeet. A guide to the spoken Blackfeftt Indian language andexamples of the language with English translations are also provided, asis information on sign language and picture writing. The constitutionand by-laws for the Blackfeet Tribe, a glossary of terms, and abibliography of books, films, tapes, and maps are also included. (IS) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EOU CATION POSITION OR POLICY le TABLE OF CONTBTTS Introductio Acknowledgement-- Cover Page -- Pronunciation of Indian Names Chapter I - History A Generalized View The Early Hunters 7 8 The Foragers The Late Hunters - -------- ----- Culture of the Late Hunters - - - - ---------- --- ---- ---9 The plains Tribes -- ---- - ---- ------11 The BlaLkfeet -

Social Networking Service History

Social Networking Service A social networking service is an online service, platform, or site that focuses on building and reflecting of social networks or social relations among people, who, for example, share interests and/or activities. A social network service essentially consists of a representation of each user (often a profile), his/her social links, and a variety of additional services. Most social network services are web based and provide means for users to interact over the Internet, such as e-mail and instant messaging. Online community services are sometimes considered as a social network service, though in a broader sense, social network service usually means an individual-centered service whereas online community services are group-centered. Social networking sites allow users to share ideas, activities, events, and interests within their individual networks. The main types of social networking services are those which contain category places (such as former school year or classmates), means to connect with friends (usually with self- description pages) and a recommendation system linked to trust. Popular methods now combine many of these, with Facebook and Twitter widely used worldwide, Nexopia (mostly in Canada); Bebo, VKontakte, Hi5, Hyves (mostly in The Netherlands), Draugiem.lv (mostly in Latvia), StudiVZ (mostly in Germany), iWiW (mostly in Hungary), Tuenti (mostly in Spain), Nasza-Klasa (mostly in Poland), Decayenne, Tagged, XING, Badoo and Skyrock in parts of Europe; Orkut and Hi5 in South America and Central America; and Mixi, Multiply, Orkut, Wretch, renren and Cyworld in Asia and the Pacific Islands and LinkedIn and Orkut are very popular in India.