Continuity and Change in Canadian Conservative Campaign Rhetoric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Stephen Harper

HARPER Edited by Teresa Healy www.policyalternatives.ca Photo: Hanson/THE Tom CANADIAN PRESS Understanding Stephen Harper The long view Steve Patten CANAdIANs Need to understand the political and ideological tem- perament of politicians like Stephen Harper — men and women who aspire to political leadership. While we can gain important insights by reviewing the Harper gov- ernment’s policies and record since the 2006 election, it is also essential that we step back and take a longer view, considering Stephen Harper’s two decades of political involvement prior to winning the country’s highest political office. What does Harper’s long record of engagement in conservative politics tell us about his political character? This chapter is organized around a series of questions about Stephen Harper’s political and ideological character. Is he really, as his support- ers claim, “the smartest guy in the room”? To what extent is he a con- servative ideologue versus being a political pragmatist? What type of conservatism does he embrace? What does the company he keeps tell us about his political character? I will argue that Stephen Harper is an economic conservative whose early political motivations were deeply ideological. While his keen sense of strategic pragmatism has allowed him to make peace with both conservative populism and the tradition- alism of social conservatism, he continues to marginalize red toryism within the Canadian conservative family. He surrounds himself with Governance 25 like-minded conservatives and retains a long-held desire to transform Canada in his conservative image. The smartest guy in the room, or the most strategic? When Stephen Harper first came to the attention of political observers, it was as one of the leading “thinkers” behind the fledgling Reform Party of Canada. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation

Global Media Journal German Edition From the field An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation Andrej Školkay1 Abstract: This is a study of suggested approaches to social media regulation based on an explora- tory methodological approach. Its first aim is to provide an overview of the global and local debates and the main arguments and concerns, and second, to systematise this in order to construct taxon- omies. Despite its methodological limitations, the study provides new insights into this very rele- vant global and local policy debate. We found that there are trends in regulatory policymaking to- wards both innovative and radical approaches but also towards approaches of copying broadcast media regulation to the sphere of social media. In contrast, traditional self- and co-regulatory ap- proaches seem to have been, by and large, abandoned as the preferred regulatory approaches. The study discusses these regulatory approaches as presented in global and selected local, mostly Euro- pean and US discourses in three analytical groups based on the intensity of suggested regulatory intervention. Keywords: social media, regulation, hate speech, fake news, EU, USA, media policy, platforms Author information: Dr. Andrej Školkay is director of research at the School of Communication and Media, Bratislava, Slovakia. He has published widely on media and politics, especially on political communication, but also on ethics, media regulation, populism, and media law in Slovakia and abroad. His most recent book is Media Law in Slovakia (Kluwer Publishers, 2016). Dr. Školkay has been a leader of national research teams in the H2020 Projects COMPACT (CSA - 2017-2020), DEMOS (RIA - 2018-2021), FP7 Projects MEDIADEM (2010-2013) and ANTICORRP (2013-2017), as well as Media Plurality Monitor (2015). -

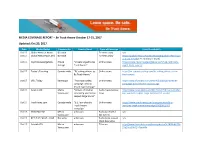

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017 Date Media Outlet Community Header/Lead Type of Coverage Link (if available) Oct 17 Global News at Noon BC-wide TV news story n/a Oct 17 Global News Hours at 6 BC-wide TV news story https://globalnews.ca/video/3810220/global-news-hour- at-6-oct-17-4 (at 21:14 minute mark) Oct 17 MyPrinceGeorgeNow Prince “Drivers Urged to Be Online news https://www.myprincegeorgenow.com/59471/drivers- George Truck Aware” urged-truck-aware/ Oct 17 Today’s Trucking Canada-wide “BC asking drivers to Online news https://m.todaystrucking.com/bc-asking-drivers-to-be- Be Truck Aware” truck-aware Oct 17 CFJC Today Kamloops “Provincial safety Online news http://www.cfjctoday.com/article/592118/provincial- campaign aims to campaign-aims-lessen-road-carnage lessen road carnage” Oct 17 News 1130 Metro “Drivers of smaller Radio News/online http://www.news1130.com/2017/10/17/drivers-smaller- Vancouver cars being warned to news cars-warned-respect-large-commercial-trucks/ respect large trucks” Oct 17 TruckNews.com Canada-wide “B.C. launches Be Online news https://www.trucknews.com/transportation/b-c- Truck Aware launches-truck-aware-campaign/1003081520/ campaign” Oct 17 CKYE RED FM Metro unknown Radio (attended n/a Vancouver the event) Oct 17 97.3 THE EAGLE - CKLR Nanaimo unknown Radio (interviewed n/a Mark Donnelly) Oct 17 Fairchild TV Metro unknown TV news http://www.fairchildtv.com/news.php?n=5c2868adb73b Vancouver 23a26ca29b7244babfdb Oct 17 Kamloopscity.com Kamloops “Drivers urged to -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

Insight Trudeau Without Cheers Assessing 10 Years of Intergovernmental Relations

IRPP Harper without Jeers, Insight Trudeau without Cheers Assessing 10 Years of Intergovernmental Relations September 2016 | No. 8 Christopher Dunn Summary ■■ Stephen Harper’s approach to intergovernmental relations shifted somewhat from the “open federalism” that informed his initial years as prime minister toward greater multilateral engagement with provincial governments and certain unilateral moves. ■■ Harper left a legacy of smaller government and greater provincial self-reliance. ■■ Justin Trudeau focuses on collaboration and partnership, including with Indigenous peoples, but it is too early to assess results. Sommaire ■■ En matière de relations intergouvernementales, l’approche de Stephen Harper s’est progressivement éloignée du « fédéralisme ouvert » de ses premières années au pouvoir au profit d’un plus fort engagement multilatéral auprès des provinces, ponctué ici et là de poussées d’unilatéralisme. ■■ Gouvernement réduit et autonomie provinciale accrue sont deux éléments clés de l’héritage de Stephen Harper. ■■ Justin Trudeau privilégie la collaboration et les partenariats, y compris avec les peuples autochtones, mais il est encore trop tôt pour mesurer les résultats de sa démarche. WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS IN CANADA? Surprises. In October 2015, we had an election with a surprise ending. The Liberal Party, which had been third in the polls for months, won a clear majority. The new prime minister, Justin Trudeau, provided more surprises, engaging in a whirl- wind of talks with first ministers as a group and with social partners that the previous government, led by Stephen Harper, had largely ignored. He promised a new covenant with Indigenous peoples, the extent of which surprised even them. Change was in the air. -

Hebi Sani: Mental Well Being Among the Working Class Afro-Surinamese in Paramaribo, Suriname

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME Aminata Cairo University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cairo, Aminata, "HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME" (2007). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 490. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/490 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aminata Cairo The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME ____________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aminata Cairo Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Deborah L. Crooks, Professor of Anthropology Lexington, Kentucky 2007 Copyright © Aminata Cairo 2007 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE -

Optik TV Channel Listing Guide 2020

Optik TV ® Channel Guide Essentials Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver/ Kelowna/ Prince Dawson Victoria/ Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel Cranbrook McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 Alberta Assembly TV ABLEG 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● AMI-audio* AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé* AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv* AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West)* ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 — APTN HD* APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 — BC Legislative TV* BCLEG — — — — — — — — 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 CBC Calgary* CBRTDT ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC Edmonton* CBXTDT 100 100 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC News Network CBNEWHD 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 CBC Vancouver* CBUTDT ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 CBS Seattle KIRODT 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 CHEK* CHEKDT — — — — — — — — 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 Citytv Calgary* CKALDT ● ● ● ● ● 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Edmonton* CKEMDT 106 106 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Vancouver* -

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends

Quarterly Report to Members, Subscribers and Friends First Quarter, 2015 Q1 highlights: effective and efficient policy research & outreach Q1 research 14 research papers 3 Verbatims 2 Monetary Policy Council releases Q1 policy events 11 policy events and special meetings, including: Montreal Roundtable – Sophie Brochu, President and CEO, Gaz Métro Ottawa Roundtable - Lt. Gen. Charles Bouchard, Country Leader, Lockheed Martin Canada Toronto Roundtable – Mitzie Hunter, Associate Minister of Finance, Ontario Calgary Roundtable – Ian Telfer, Chairman of the Board, Goldcorp Policy Outreach in Q1 109,032 website pageviews 12 policy outreach presentations 34 National Post and Globe and Mail citations Citations in more than 80 media outlets 36 media interviews 20 opinion and editorial pieces 2 Q1 select policy influence Health papers receive national recognition including acknowledgements by senior government officials Nova Scotia’s Health Minister acknowledged the province’s looming fiscal burden while responding to an Institute paper and the Federal Leader of Liberal Party cited the Institute’s recent vaccination study. Reports: Delivering Healthcare to an Aging Population: Nova Scotia’s Fiscal Glacier and A Shot in the Arm: How to Improve Vaccination Policy in Canada Op-Eds: New Brunswick’s demographic challenge: Telegraph- Journal Op-Ed and Booster shot for Ontario’s vaccination policies: Toronto Star Op-Ed Alberta budget is presented on a fully consolidated basis in a format supported by the Auditor General Alberta Finance Minister acknowledged that more clarity is needed in budget presentation after the Institute gave the province a C grade. Report: Credibility on the (Bottom) Line: The Fiscal Accountability of Canada’s Senior Governments, 2013 Op-Eds: A decade of government overspending has left us over-taxed and deeper in debt: Globe and Mail Op- Ed, Saskatchewan budget – Adding up the numbers: Leader-Post Op-Ed Canada and U.S. -

Was Stephen Harper Really Tough on Crime? a Systems and Symbolic Action Analysis

Was Stephen Harper Really Tough on Crime? A Systems and Symbolic Action Analysis A thesis submitted to The College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Sociology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Mark Jacob Stobbe ©Mark Jacob Stobbe, September 2018. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirement for a postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or part, for scholarly purposes, may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis was done. It is understood that any copying, publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Request for permission to copy or use of whole or part of this thesis may be addressed to: Department of Sociology University of Saskatchewan 1019 - 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, SK Canada S7N 5A5 OR College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan Room 116 Thorvaldson Building, 110 Science Place Saskatoon SK Canada S7N 5C9 i ABSTRACT In 2006, the Hon. -

Prime Ministers and Government Spending: a Retrospective by Jason Clemens and Milagros Palacios

FRASER RESEARCH BULLETIN May 2017 Prime Ministers and Government Spending: A Retrospective by Jason Clemens and Milagros Palacios Summary however, is largely explained by the rapid drop in expenditures following World War I. This essay measures the level of per-person Among post-World War II prime ministers, program spending undertaken annually by each Louis St. Laurent oversaw the largest annual prime minister, adjusting for inflation, since average increase in per-person spending (7.0%), 1870. 1867 to 1869 were excluded due to a lack though this spending was partly influenced by of inflation data. the Korean War. Per-person spending spiked during World Our current prime minister, Justin Trudeau, War I (under Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden) has the third-highest average annual per-per- but essentially returned to pre-war levels once son spending increases (5.2%). This is almost the war ended. The same is not true of World a full percentage point higher than his father, War II (William Lyon Mackenzie King). Per- Pierre E. Trudeau, who recorded average an- person spending stabilized at a permanently nual increases of 4.5%. higher level after the end of that war. Prime Minister Joe Clark holds the record The highest single year of per-person spend- for the largest average annual post-World ing ($8,375) between 1870 and 2017 was in the War II decline in per-person spending (4.8%), 2009 recession under Prime Minister Harper. though his tenure was less than a year. Prime Minister Arthur Meighen (1920 – 1921) Both Prime Ministers Brian Mulroney and recorded the largest average annual decline Jean Chretien recorded average annual per- in per-person spending (-23.1%). -

In the National Interest: Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909–2009

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2011 In the National Interest: Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909–2009 University of Calgary Press Donaghy, G., & Carroll, M. (Eds.). (2011). In the National Interest: Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909-2009. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48549 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com IN THE NATIONAL INTEREST Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909–2009 Greg Donaghy and Michael K. Carroll, Editors ISBN 978-1-55238-561-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright.