REORGANIZATION of the PUBLIC Sea00 L SYSTEM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b B No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) Expires Jan. 2005) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several 'n ow *° Comp/ete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requestedirrforTiaTi dditional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing HISTORIC PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF KANSAS B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each. THE AMERICAN EDUCATION SYSTEM (1700 - 1955) THE EVOLUTION OF THE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM IN KANSAS (1854 - 1955) THE PUBLIC SCHOOL BUILDINGS OF KANSAS (1854 - 1955) C. Form Prepared by name/title- Brenda R. Spencer, Preservation Planning and Design street & number- 10150 Onaga Road telephone- 785-456-9857 city or town- Wamego state- KS zip code-66547 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. (__ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) C n Signature ana title of certifying official Date State or Federal Agency or Tribal government I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

2019-2020 Boston Public Schools Exam School Application Guide

2019-2020 Boston Public Schools Exam School Application Guide Boston Latin Academy Entrance to Grades 7 and 9 Boston Latin School Entrance to Grades 7 and 9 John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science Entrance to Grades 7, 9, and 10 REGISTRATION DEADLINE: SEPTEMBER 20, 2019 IN-SCHOOL TESTING (Grade 6 BPS only): THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2019 WEEKEND TEST DATE: SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2019 Register online at bostonpublicschools.org/exam Exam administered by the Educational Records Bureau under the supervision of the Boston Public Schools Language Assistance Families who need interpretation and/or translation assistance during the application process may call a BPS Welcome Center at 617-635-9010, 617-635-8015, or 617-635-8040. 2 Table of Contents 2019 – 2020 Exam School Application Checklist .......4 Exam School Admissions Process ...............................5 Step 1: Register for the Independent School Entrance Exam .....................................................6 Sunday Test .....................................................6 National Test Option ......................................6 Step 2: Request Test Accommodations for Students with Disabilities and English Language Learners ................................................7 Step 3: Residency Verification Process ................11 Step 4: Take the ISEE .........................................13 The Make-up Test .........................................15 Step 5: Rank Exam School Choices & Submit Grades ....................................................15 Step 6: -

School Architecture;

SCHOOL ARCHITKTllii: CONTRIBUTIONS ! . ' '. J' OF MllU'-i -1J... .' :. :: '' i ; !• --T \. n>. M • I J *» " l .VI. \ . I >'*. SCHOOL ARCHITECTURE; OB CONTRIBUTIONS IMPROVEMENT OF SCHOOL-HOUSES IB J . THE UNITED STATES. BY HENUYj-BARMRD, COMMISSIONER OF PU.fl ,1C . HOHOOUI IN. RliODI ISLAND. SECOND EDITION. NEW YORK: PUBLISHED BY A. S. BARNES & CO. CINCINNATI :— H. W. DERBY & CO. 1848. PREFACE. The following contribution to the improvement of school-houses, was originally prepared by the author in 1838, as one of a series of addresses designed for popular and miscellaneous audiences, and as such, was delivered in various towns in Connecticut during the four years he acted as Secretary of the Board of Commissioners of Common Schools for that State. It was printed for the first time in the Connecticut Common School Journal in the winter of 1841; and again, in 1842, as one of the documents appended to his Annual Report to the Board for that year. Since that date it has been repeatedly published, each time with addi tional plans anc descriptions of new and convenient school-houses, until upwards of twenty thousand copies have been gratuitously circulated in the States whcr.; tiie author has been called upon to labor in the cause of common-school improvement, or among the friends of popular educa tion in other parts of the country. At the suggestion of many of these friends, the work has been put into the hands of a publishing house, to be brought before the public, in the hope . that it, miy still continue to help those who are looking round for* approved pLins of school-houses, by introducing them to the ies,ulta of much'study, observation and experi ence on the part of many laborers in.t^is department of public education. -

A Souvenir of Massachusetts Legislators

&sm&& mS^mm^^mmMS^Smss^m 3s A •i. SsSSfs^^MBSSSSSswiMr., JL SGJUyENIR%*> > OF • i M m 5 Sft C H U S ET-T'§ LEGIBM.T-eRS; 189a. ^ lj BY AT M. BRIDGMAN. M SfM^ LIBRA W OF ASSMHISBII OCT 9 1947 6TA»£ HUUbt, BOSTON ' A<f. BRID The half-tone engravings in this printed by book were made on copper by the Wright & Potter Printing Co. Art Publishing Company, 18 Post Office Square, 132 Boylston Street. Boston. Mass 3s ?2 PREFACE. ~¥"N this souvenir volume an entirely new method lias been followed. The legislators who -*- have worked together are here grouped together. The chairman has been iriven the place of honor in the centre, with the House chairman on his right and the clerk on his left. The other members are then placed as in the committee arrangement. Fur evident reasons, how- ever, there is an occasional departure from this rule. The councillors and members of Congress are arranged in order by their districts. The aim of the editor has been to produce a book that should contain such matters of special interest as could not be found in any official publication. Therefore, whatever appears in the regular journals of either branch has been excluded, because this would be only a duplication. But here is given the personality of our legislators, as well as of other state officers. Here are their counterfeit presentment, their biography, and the fac-simile of their auto- graphs. All these make up the -man ; and here are the men who made laws for their state and helped make them for the nation in 1892. -

Ocm08580879-1910.Pdf (12.88Mb)

A SOUVENIR OF Massachusetts Legislators 1910 VOLUME XIX (Issued Annually) ./ A. M, BRIDGMAN STOUGHTON, MASS. OCT 21 1910 a.vvA, - STATE HOUSE, BOSTON. PREFACE The Legislature of igio passed more bills than any other on rec- ord. And that was not its only claim to distinction. It had a genuine "investigation." that of the Lyman School; a couple of "near investi- gations"—the milk question and the Southbridge Savings bank irregu- larities; also it authorized the investigation by special commissions of "The High Cost of Living" and of the securities of the N. Y., N. H. & H. R. R. Company. The results of these investigations must be sought in the daily papers. They served the usual and chief end of all investigations— that of a safety-valve and a scapegoat, to use a mixed metaphor. The tax payers foot the bills; and if they are sat- isfied certainly the investigators ought to be. Taken altogether it was a very "strenuous" session. Corporation questions were again prominent; the farmers came into "the limelight" more than ever; labor issues were tangled up with liquor issues; Columbus got a state holiday in his honor, which was refused Lincoln; the widow of the Confederate General Pickett was received with applause in the House, to which she made a brief address; the Legislative dinner at the Quincy House was something not to be forgotten: the mock session of the afternoon of prorogation was orderly and decorous to an un- known degree, but was marred by the disorder of the subsequent evening, the Republicans wcr- alleged to be directed by a prominent Democrat; an unus;ua.i iuiinher o ( 'booms" wtrli bunched: the Repub- licans had their "insurgents" and f hc Democrats their Riley; the House was adjourned out of respec to the funeral of King Edward, an act without precedent but most commendable and honored as such 1 for by the English vbe-corsu iji Hon".-]: .mllio-is vfrerc appropriated East and South iloston 'harbor' improvements; it passed "sane and safe" fireworks legislation. -

Partnerships for Student Success

PARTNERSHIPS FOR STUDENT SUCCESS Providing Youth with Quality Programs Through the FY2013 Quality Enhancements in After School and Out of School Grant LINE ITEM 7061-9611 A REPORT TO THE MASSACHUSETTS LEGISLATURE 7061-9611: THE AFTER SCHOOL AND OUT OF SCHOOL TIME QUALITY ENHANCEMENT GRANT HERE I’VE LEARNED THAT “EDUCATION IS THE KEY. AND WHEN YOU HAVE THE KEY, THEY CAN’T LOCK YOU OUT. – Oscar, age 18, Participant in ASOST Funded Program” ASOST LINE ITEM 7061-9611 AT A GLANCE The After School and Out of School Time (ASOST) Quality Enhancement Grant line item 7061-9611 is an innovative and effective grant program that provides high quality expanded learning opportunities (ELOs) before school, after school and during the summer months to students across the state of Massachusetts. Public school districts, non-public schools, or community based organizations (CBOs) with existing out of school time programs are eligible to apply for up to $25,000 in funding to implement quality enhancements, reduce barriers to participation, and expand programming into the summer months. This report details the opportunities in ASOST around the Commonwealth and what the legislature can do to help close the achievement gap and provide healthy, quality, academic afterschool environments for our youth. ASOST-Q HELPS MASSACHUSETTS YOUTH MOST IN NEED 11,222 CHILDREN The ASOST Quality Grant is the only state-funded program dedicated to increasing high quality learning opportunities for children and youth before school, afterschool, and during the summer. AND YOUTH The ASOST Quality Grant program represents an essential component of the Commonwealth’s DIRECTLY innovative education agenda and complements the tools and strategies of the Achievement Gap Act BENEFIT FROM of 2010 that support student success and have made Massachusetts a national leader in education. -

19 April 2021 File No. 133860-003 US Environmental Protection Agency

HALEY & ALDRICH, INC. 465 Medford St. Suite 2200 Boston, MA 02129 617.886.7400 19 April 2021 File No. 133860-003 US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Ecosystem Protection 5 Post Office Square – Suite 100 (OEP06-01) Boston, MA 02109-3912 Attention: EPA/OEP RGP Applications Coordinator Subject: Notice of Intent (NOI) Temporary Construction Dewatering 15 Necco Street Boston, Massachusetts Ladies and Gentlemen, On behalf of our client, ARE-MA Region No. 74 LLC, and in accordance with the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Remediation General Permit (RGP) in Massachusetts, MAG910000, this letter submits a Notice of Intent (NOI) in Appendix A and the applicable documentation as required by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for temporary construction site dewatering under the RGP. Haley & Aldrich, Inc. (Haley & Aldrich) has prepared this submission to facilitate off-site discharge of temporary dewatering during construction activities at the 15 Necco Street site in Boston, Massachusetts (the “site”). SITE LOCATION AND HISTORICAL SITE USAGE The approximately 45,000 square foot (sq ft) site is located at 15 Necco Street in Boston, Massachusetts, as shown in Figure 1. The site is currently a vacant paved lot. The site was most recently used as a laydown area for the adjacent development at 5 and 6 Necco Court. The site is bordered by 6-story brick office building at 5 and 6 Necco Court to the north; paved parking lots (planned for future redevelopment) to the south; Necco Street to the east, beyond which is a parking garage; and the Boston Harbor Walk and Fort Point Channel to the west. -

Re: Notice of Intent for the Remediation General Permit Temporary Construction Dewatering for Demolition 776 Summer Street, South Boston, Massachusetts

1 Technology Park Drive 1 TechnologyWestford, Park MA 01886Drive Westford, MA 01886 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency March 23, 2021 Office of Ecosystem Protection File No. 4867.00 EPA/OEP RGP Applications Coordinator 5 Post Office Square, Suite 100 (OEP06-01) Boston, MA 02109-3912 Re: Notice of Intent for the Remediation General Permit Temporary Construction Dewatering for Demolition 776 Summer Street, South Boston, Massachusetts Dear Sir/Madam: On behalf of HRP 776 Summer Street, LLC (HRP), Sanborn, Head & Associates, Inc. (Sanborn Head) is submitting this Notice of Intent (NOI) to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) for coverage under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Remediation General Permit (RGP) MAG910000 for 776 Summer Street in South Boston, Massachusetts (the Site). This letter and supporting documentation were prepared in accordance with the USEPA guidance for construction dewatering under the RGP program. HRP is the owner of the Site and will have responsibility for the contractors/subcontractors performing the dewatering activities at the Site. Contractors and subcontractors working for HRP on the project will be required to meet the requirements of this NOI and the RGP. The location of the Site and the discharge locations into the Reserved Channel via private on- Site storm water catch basins are shown on Figure 1 and Figure 2. The Site is approximately 15 acres and was previously operated as the New Boston Generating Station. The first phase of redevelopment activities at the Site include removal of various structures and foundations on the Site, selective demolition of structures that are anticipated to remain and be redeveloped, removal of various infrastructure elements including but not limited to, below grade piping systems, storm water systems, electrical distribution components, and various equipment bases and pads throughout the Site. -

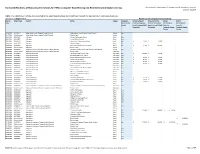

DESE Tech Readiness Spreadsheet

Estimated Readiness of Massachusetts Schools for PARCC Computer-Based Testing and Next-Generation Digital Learning Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education October 10, 2014 NOTE: This information reflects data reported to the Department by local district officials through the online PARCC Technology Readiness Survey as of August 2014. Readiness for Computer-Based Testing District School Code District School Region Computer- School Computer School Computer School District Code Based Testing Costs for Computer- Costs for Computer- Infrastructure Infrastructure Ready? Based Testing ($250/ Based Testing ($1000/ Costs for Costs for Computer) Computer) Computer-Based Computer-Based Testing Testing 04450000 04450105 Abby Kelley Foster Charter Public (District) Abby Kelley Foster Charter Public School Urban Yes 04450000 District-Level Abby Kelley Foster Charter Public (District) District-Level Urban 00010000 00010002 Abington Center Elementary School Rural Yes 00010000 00010405 Abington Frolio Middle School Rural Yes 00010000 00010015 Abington Woodsdale Elementary School Rural No $ 1,500 $ 6,000 00010000 00010505 Abington Abington High Rural Yes 00010000 00010003 Abington Beaver Brook Elementary School Rural No $ 2,750 $ 11,000 00010000 District-Level Abington District-Level Urban 04120000 04120530 Academy Of the Pacific Rim Charter Public (District) Academy Of the Pacific Rim Charter Public School Urban Yes 04120000 District-Level Academy Of the Pacific Rim Charter Public (District) District-Level Suburban 06000000 06000405 Acton-Boxborough Raymond J Grey Junior High Suburban No $ 19,000 $ 76,000 06000000 06000005 Acton-Boxborough Blanchard Memorial School Suburban Yes 06000000 06000025 Acton-Boxborough Paul P Gates Elementary School Suburban No $ 8,250 $ 33,000 06000000 06000030 Acton-Boxborough Luther Conant School Suburban No $ 8,500 $ 34,000 06000000 06000015 Acton-Boxborough McCarthy-Towne School Suburban No $ 8,250 $ 33,000 06000000 06000020 Acton-Boxborough C.T. -

M E M O R a N D U M

Office of the Superintendent Tommy Chang, Ed.D., Superintendent th 2300 Washington Street, 5 Floor [email protected] Roxbury, Massachusetts 02119 617-635-9050 bostonpublicschools.org M E M O R A N D U M TO: Chairperson and Members Boston School Committee FROM: Tommy Chang Superintendent SUBJECT: Grants for Approval DATE: July 11, 2017 Attached please find the grants that will be put forth for School Committee approval on July 19, 2017. Should you wish to review the proposals in more detail, the complete grant proposals have been filed with the Office of the Secretary to the School Committee. If you have any questions, staff is available to respond. Attachment cc: Inez Foster, Assistant Director, Resource Development Mayor's Office of Intergovernmental Relations Boston Public Schools Boston School Committee City of Boston Tommy Chang, Superintendent Michael D. O’Neill, Chair Martin J. Walsh, Mayor Finance Department Eleanor Laurans, Chief Financial Officer 2300 Washington Street [email protected] Roxbury, Massachusetts 02119 617-635-8306 bostonpublicschools.org M E M O R A N D U M TO: Tommy Chang Superintendent FROM: Eleanor Laurans Chief Financial Officer SUBJECT: Grants for Approval DATE: July 11, 2017 Attached please find the grants for approval by the School Committee on July 19, 2017. Full copies of the grant proposals are available for your review and have been filed with the Office of the Secretary to the School Committee. Boston Public Schools Boston School Committee City of Boston Tommy Chang,