The Scots in Sweden Part Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

Euriskodata Rare Book Series

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE HI S T KY o F SCANDINAVIA. HISTOEY OF SCANDINAVIA. gxm tilt €mI% f iiius NORSEMEN AND YIKINGS TO THE PRESENT DAY. BY THE EEV. PAUL C. SINDOG, OF COPENHAGEN. professor of t^e Scanlimafaian fLanguagts anD iLifnaturr, IN THE UNIVERSITY OF THE CITY OF NEW-YORK. Nonforte ac temere humana negotia aguntur atque volvuntur.—Curtius. SECOND EDITION. NEW-YORK: PUDNEY & RUSSELL, PUBLISHERS. 1859. Entered aceordinfj to Act of Congress, in the year 1858, By the rev. PAUL C. SIN DING, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States, for the Southern Distriftt of New-York. TO JAMES LENOX, ESQ., OF THE CUT OF NEW-TOBK, ^ht "^nu of "^ttttxs, THE CHIIISTIAN- GENTLEMAN, AND THE STRANGER'S FRIEND, THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED, BY THE AUTHOR PREFACE. Although soon after my arrival in the city of New-York, about two years ago, learning by experience, what already long had been known to me, the great attention the enlightened popu- lation of the United States pay to science and the arts, and that they admit that unquestion- able truth, that the very best blessings are the intellectual, I was, however, soon . aware, that Scandinavian affairs were too little known in this country. Induced by that ardent patriotism peculiar to the Norsemen, I immediately re- solved, as far as it lay in my power, to throw some light upon this, here, almost terra incog- nita, and compose a brief History of Scandinavia, which once was the arbiter of the European sycjtem, and by which America, in reality, had been discovered as much as upwards of five Vlll PREFACE centuries before Columbus reached St. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Anglo-Saxon Coins Found in Finland, and to This End He Compiled a List of the Same

U I LLINOI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Brittle Books Project, 2012. COPYRIGHT NOTIFICATION In Public Domain. Published prior to 1923. This digital copy was made from the printed version held by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It was made in compliance with copyright law. Prepared for the Brittle Books Project, Main Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign by Northern Micrographics Brookhaven Bindery La Crosse, Wisconsin 2012 ANGLO-SAXON COINS FOUND IN FINLAND. ANGLO-SAXON COINS FOUND IN FINLAND BY C. A. NORDMAN HELSINGFORS 1921 HELSINOFORS 1921. PRINTED BY HOLGER SCHILDT . PREFACE. The late Mr. O. Alcenius had designs on a publication treating of the Anglo-Saxon coins found in Finland, and to this end he compiled a list of the same. One part of this list containing most of the coins of Aethelred, along with a short introduction, was printed already, but owing to some cause or other the issue of the essay was discontinued some time before the death of the author. Although the original list has not now been found fit for use, 'the investigations of Mr. Alcenius have anyhow been of good service for the composition of this paper. The list now appears in a revised and also completed form. Further on in this essay short descriptions of the coin types have been inserted before the list of the coins of each king, and there has been an attempt made to a chronological arrangement of the types. Mr. Alcenius also tried to fix the relative and absolute chronology of the coins of Aethelred, but I regret to say that I could not take the same point of view as he as to the sequence of the types. -

2020-21 Faculty Book

Gustavus Adolphus College Saint Peter, Minnesota 2020-21 Faculty Book CONTENTS All-College Policies (Gray Pages) Faculty Committees (Green Pages) Faculty Handbook (Yellow Pages) Faculty Manual (Blue Pages) Governing Documents (Purple Pages) Shared Governance Principles (White Pages) All-College Policies, 2020-21 All-College Policies, 2020-21 ............................................................................................................................................ 1 To the Gustavus Community ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Access to Student Records ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Alcohol Serving Policy ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Bereavement Policy ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Cancellation/Delay/Closure Policy ................................................................................................................................. 3 Compensation Certification Policy .................................................................................................................................. 5 Conflict of Interest Policy for Committee Participation -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free

Issue 63: How the Vikings Took up the Faith Conversion of the Vikings: Did You Know? Fascinating and little-known facts about the Vikings and their times. What's a Viking? To the Franks, they were Northmen or Danes (no matter if they were from Denmark or not). The English called them Danes and heathens. To the Irish, they were pagans. Eastern Europe called them the Rus. But the Norse term is the one that stuck: Vikings. The name probably came from the Norse word vik, meaning "bay" or "creek," or from the Vik area, the body of water now called Skagerrak, which sits between Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. In any case, it probably first referred only to the raiders (víkingr means pirate) and was later applied to Scandinavians as a whole between the time of the Lindesfarne raid (793) and the Battle of Hastings (1066). Thank the gods it's Frigg's day. Though Vikings have a reputation for hit-and-run raiding, Vikings actually settled down and influenced European culture long after the fires of invasion burned out. For example, many English words have roots in Scandinavian speech: take, window, husband, sky, anger, low, scant, loose, ugly, wrong, happy, thrive, ill, die, beer, anchor. … The most acute example is our days of the week. Originally the Romans named days for the seven most important celestial bodies (sun, moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn). The Anglo-Saxons inserted the names of some Norse deities, by which we now name Tuesday through Friday: the war god Tiw (Old English for Tyr), Wodin (Odin), Thor, and fertility goddess Frigg. -

The English-Language Military Historiography of Gustavus Adolphus in the Thirty Years’ War, 1900-Present Jeremy Murray

Western Illinois Historical Review © 2013 Vol. V, Spring 2013 ISSN 2153-1714 The English-Language Military Historiography of Gustavus Adolphus in the Thirty Years’ War, 1900-Present Jeremy Murray With his ascension to the throne in 1611, following the death of his father Charles IX, Gustavus Adolphus began one of the greatest reigns of any Swedish sovereign. The military exploits of Gustavus helped to ensure the establishment of a Swedish empire and Swedish prominence as a great European power. During his reign of twenty-one years Gustavus instituted significant reforms of the Swedish military. He defeated, in separate wars, Denmark, Poland, and Russia, gaining from the latter two the provinces of Ingria and Livonia. He embarked upon his greatest campaign through Germany, from 1630 to his death at the Battle of Lützen in 1632, during the Thirty Years’ War. Though Gustavus’ achievements against Denmark, Russia, and Poland did much in establishing a Swedish Baltic empire, it was his exploits during the Thirty Years’ War that has drawn the most attention among historians. It was in the Thirty Years’ War that Sweden came to be directly involved in the dealings of the rest of Europe, breaking from its usual preference for staying in the periphery. It was through this involved action that Sweden gained its place among the great powers of Europe. There is much to be said by historians on the military endeavors of Gustavus Adolphus and his role in the Thirty Years’ War. An overwhelming majority of the studies on Gustavus Adolphus in the Thirty Years’ War have been written in German, Swedish, Danish, Russian, Polish, or numerous other European languages. -

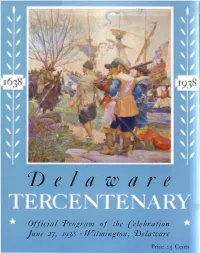

Delaware Tercentenary Program

Vela ware Official Program., of the Celebration June 27, I9J8 ·Wilmington, 'Delaware Price 25 Cents FORT CHRISTINA H.M. CHRISTINA, Queen of Sweden (r6J'l-l 654) during H.M. GusTAvus A oo LPH U s , King of Sweden (161 '· whose reign New Sweden was founded. I 632) through whose support New Sweden becan1e a possibility. l DEcEMBER 1637, the Swedish Expedi tion, under Peter Minuit, sailed from Sweden in the ship, "Kalmar Nyckel" and the yacht,"Fogel Grip," and finally reached the "Rocks" in March r6J8. Here Minui t made a treaty with the Indians and, with a salute of two cannons, claimed for Sweden all that land from the Christina River down to Bombay Hook. Wt�forl(g� ?t�dfantt� �fnur }llttttbetaCONTRACTET gnga(n�cat�ct S�bre �mpagnict �tbf J(onuugart;rctj ewcrfg�c. 6rdlc iam·om �it�dm &\jffdin�. £)�uu 4/ft6tt 9?tl)trfdnb(rc �prdfct �fau p.S6�Mnfl.al 2ft' ~ £ BEGINNINGS of the establishment of New }:RICO SCHRODERO. L S~eden rnay be traced back to the efforts of one William Usselinx, a native of Antwerp, who interested King Gustavus Adolphus in the enter prise. At the right is reproduced the cover of the contract and prospectus which was used to interest The Cover investors in the venture. Here is reproduced the famous painting by Stanley M. Arthurs, Esq., ofthe landing ofthe .firstSwedish expedi tion at the "Roclcs." The painting is owned by Joseph S. Wilson, Esq. GusTAF V ' K.lng • of S weden , d u r .1 n g . w h ose reign, In I9J8 , t h e ter- centenary of · the found·lng of N ew Sweden IS celebrated. -

Petersburg Aug 3 Or July 22D for We Are Very Lazy Between Our Own + the Russian Calendar

Petersburg Aug 3 or July 22d for we are very lazy between our own + the Russian calendar. My dear Dora. We arrived here in the middle of the day today + found Larry’s letter of July 18th. We can’t imagine why you have not heard regularly, particularly as Mrs. Suydam has done so, + the letters were posted together. At any rate, we have written “in a concatenation accordingly.” So glad you are all well + happy. I trust dear little [Hip’s?]’s hair won’t come out darker + that he is well again. L’s typewritten letters don’t say anything but “All well” but we are glad enough to get them all the same. I am scratching “entre chien et loup,” for there is some night here, to save the mail. We have been to [illegible] (only the untraveled say Saint to Church or City) + were amazed at its size + magnificence + the music was sublime! But to go back to where Papa left you. We had to stay four nights in Stockholm, before we cld get a passage in the steamer + then we had to take the Captain’s Cabin + all turn in together. Happily Mary, like Fanny Dorrit, has “no nonsense about her” + so we had a prosperous + smooth voyage. We stopped four hours at Helsingfors + landed to see what Finland was like. It was a handsome city + very civilized. Tomorrow we begin to sightsee in earnest. We shall deliver our letter to Mr. Wurts, + Dr. Wurts sent us another for the Hermitage is closed this month + we hope his interest may get us a sight. -

Campus History

‘SONGS OF THY TRIUMPH’ A SHORT HISTORY OF GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS COLLEGE by Steve Waldhauser ’70 PART ONE: BEGINNINGS (1862–1890) In May of 1862, the congregation of Swedish Lutheran immigrants in Red Wing, Minn., appropriated 20 dollars so that their pastor, Eric Norelius, could equip their church for parochial school purposes. The other dozen congregations of the Minnesota Conference, part of the new Augustana Synod organized in 1860, were crying for trained pastors and teachers and, as Norelius was already influential among Swedish Lutherans in Minnesota, the conference now looked to him to instruct not only the children of his own congregation but also “older” students that other congregations might send to him. From that unlikely education experiment came Gustavus Adolphus College. The first “older” student at Norelius’s school was Jonas Magny (formerly Magnuson), a 20-year-old from the Chisago Lake Swedish community who arrived in Red Wing in late September 1862, joined the Norelius household, and was in fact the only student throughout the fall. Five students from the Carver congregation arrived in December after Norelius sent word to fellow pastors that “a school for Swedes” would open in the winter, and by the middle of January 1863, enrollment had reached 11 (not counting his own congregation’s children). The school was coeducational from the beginning, some 20 years before any other Augustana institution could be called the same. The school was a short-term project for Norelius, but it was successful enough that the Minnesota Conference was willing to adopt it. The conference voted to relocate the school in East Union, a rural settlement in Carver County, and referred the matter to the Augustana Synod, which already was supporting Augustana College and Theological Seminary in Chicago. -

Local Adaptation, Consensus, and Military Conscription in Karl XI's Sweden

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2020 Negotiating for Efficiency: Local Adaptation, Consensus, and Military Conscription in Karl XI's Sweden Zachariah L. Jett Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Jett, Zachariah L., "Negotiating for Efficiency: Local Adaptation, Consensus, and Military Conscription in Karl XI's Sweden" (2020). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 2372. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/2372 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEGOTIATING FOR EFFICIENCY: LOCAL ADAPTATION, CONSENSUS, AND MILITARY CONSCRIPTION IN KARL XI’S SWEDEN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By ZACHARIAH L. JETT B.A., University Of Washington, 2015 2020 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL October 20, 2020 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Zachariah L. Jett ENTITLED Negotiating for Efficiency: Local Adaptation, Consensus, and Military Conscription in Karl XI’s Sweden BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. __________________________ Paul D. Lockhart, Ph.D. Thesis Director __________________________ Jonathan R. Winkler, Ph.D. Chair, Department of History Committee on Final Examination: ________________________________ Paul D. Lockhart, Ph.D. ________________________________ Kathryn B. Meyer, Ph.D. -

Life and Cult of Cnut the Holy the First Royal Saint of Denmark

Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Edited by: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Report from an interdisciplinary research seminar in Odense. November 6th to 7th 2017 Edited by: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Kulturhistoriske studier i centralitet – Archaeological and Historical Studies in Centrality, vol. 4, 2019 Forskningscenter Centrum – Odense Bys Museer Syddansk Univeristetsforlag/University Press of Southern Denmark Report from an interdisciplinary research seminar in Odense. November 6th to 7th 2017 Published by Forskningscenter Centrum – Odense City Museums – University Press of Southern Denmark ISBN: 9788790267353 © The editors and the respective authors Editors: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Graphic design: Bjørn Koch Klausen Frontcover: Detail from a St Oswald reliquary in the Hildesheim Cathedral Museum, c. 1185-89. © Dommuseum Hildesheim. Photo: Florian Monheim, 2016. Backcover: Reliquary containing the reamains of St Cnut in the crypt of St Cnut’s Church. Photo: Peter Helles Eriksen, 2017. Distribution: Odense City Museums Overgade 48 DK-5000 Odense C [email protected] www.museum.odense.dk University Press of Southern Denmark Campusvej 55 DK-5230 Odense M [email protected] www.universitypress.dk 4 Content Contributors ...........................................................................................................................................6