Ladies of the Covenant LILIAS DUNBAR, Mrs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marriage Notices from the Forres Gazette 1837-1855

Moray & Nairn Family History Society Marriage Notices from the Forres Gazette 18371837----1818181855555555 Compiled by Douglas G J Stewart No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Moray & Nairn Family History Society . Copyright © 2015 Moray & Nairn Family History Society First published 2015 Published by Moray & Nairn Family History Society 2 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements .................................................................................. 4 Marriage Notices from the Forres Gazette: 1837 ......................................................................................................................... 7 1838 ......................................................................................................................... 7 1839 ....................................................................................................................... 10 1840 ....................................................................................................................... 11 1841 ....................................................................................................................... 14 1842 ....................................................................................................................... 16 1843 ...................................................................................................................... -

Hunter Bailey Phd Thesis 08.Pdf (1.357Mb)

VIA MEDIA ALIA: RECONSIDERING THE CONTROVERSIAL DOCTRINE OF UNIVERSAL REDEMPTION IN THE THEOLOGY OF JAMES FRASER OF BREA (1639-1699) A thesis submitted to New College, the School of Divinity of the University of Edinburgh in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2008 By Hunter M. Bailey M.Th. (2003) University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK M.Div. (2002) Reformed Theological Seminary, Jackson, MS, USA B.A. (1998) University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA I hereby declare that this thesis has been composed by myself and is the result of my own independent research. It has not, in any form, been submitted or accepted for any other degree or professional qualification, as specified in the regulations of the University of Edinburgh. All quotations in this thesis have been distinguished by quotation marks, and all sources of outside information have received proper acknowledgment. _________________________________ Hunter M. Bailey 16 June 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents....................................................................................................... i Acknowledgements.................................................................................................... v Abstract..................................................................................................................... vii Abbreviations............................................................................................................ ix Section A Chapter 1: An Introduction.......................................................................... -

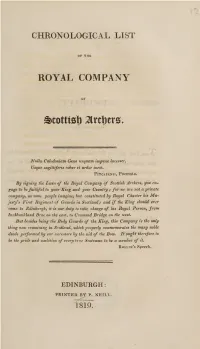

Chronological List of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF THE ROYAL COMPANY OF 2lrrt)er0. Nulla Caledoniam Gens unquarn impune laces set, Usque sagittiferis rohur et ardor inest. Pitcairnii, Poemata. By signing the Laws of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers, you en¬ gage to he faithful to your King and your Country ; for we are not a private company, as some people imagine, but constituted hy Royal Charter his Ma¬ jesty's First Regiment of Guards in Scotland; and if the King should ever come to Edinburgh, it is our duty to take charge of his Royal Person, from Inchbunkland Brae on the east, to Cramond Bridge on the west. But besides being the Body Guards of the King, this Company is the only thing now remaining in Scotland, which properly commemorates the many noble deeds performed by our ancestors by the aid of the Bow. It ought therefore to be the pride and ambition of every true Scotsman to be a member of it. Roslin’s Speech. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY P. NEII.T.. 1819. PREFACE, T he first part of the following List, is not preserved in the handwriting of the Members themselves, and is not accurate with respect to dates; but the names are copied from the oldest Minute-books of the Company which have been preserved. The list from the 13th of May 1714, is copied from the Parchment Roll, which every Member subscribes with his own hand, in presence of the Council of the Company, when he receives his Diploma. Edinburgh, 1 5th July 1819* | f I LIST OF MEMBERS ADMITTED INTO THE ROYAL COMPANY OF SCOTTISH ARCHERS, FROM 1676, Extracted from Minute-books prior to the 13th of May 1714. -

Ayrshire, Its History and Historic Families

suss ^1 HhIh Swam HSmoMBmhR Ksaessaa BMH HUB National Library of Scotland mini "B000052234* AYRSHIRE BY THE SAME AUTHOR The Kings of Carrick. A Historical Romance of the Kennedys of Ayrshire - - - - - - 5/- Historical Tales and Legends of Ayrshire - - 5/- The Lords of Cunningham. A Historical Romance of the Blood Feud of Eglinton and Glencairn - - 5/- Auld Ayr. A Study in Disappearing Men and Manners -------- Net 3/6 The Dule Tree of Cassillis - Net 3/6 Historic Ayrshire. A Collection of Historical Works treating of the County of Ayr. Two Volumes - Net 20/- Old Ayrshire Days - - - - - - Net 4/6 X AYRSHIRE Its History and Historic Families BY WILLIAM ROBERTSON VOLUME I Kilmarnock Dunlop & Drennan, "Standard" Office Ayr Stephen & Pollock 1908 CONTENTS OF VOLUME I PAGE Introduction - - i I. Early Ayrshire 3 II. In the Days of the Monasteries - 29 III. The Norse Vikings and the Battle of Largs - 45 IV. Sir William Wallace - - -57 V. Robert the Bruce ... 78 VI. Centuries on the Anvil - - - 109 VII. The Ayrshire Vendetta - - - 131 VIII. The Ayrshire Vendetta - 159 IX. The First Reformation - - - 196 X. From First Reformation to Restor- ation 218 XI. From Restoration to Highland Host 256 XII. From Highland Host to Revolution 274 XIII. Social March of the Shire—Three Hundred Years Ago - - - 300 XIV. Social March of the Shire—A Century Back 311 XV. Social March of the Shire—The Coming of the Locomotive Engine 352 XVI. The Secession in the County - - 371 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/ayrshireitshisv11908robe INTRODUCTION A work that purports to be historical may well be left to speak for itself. -

Hoofdstuk 7 Tweezijdige Puriteinse Vroomheid

VU Research Portal In God verbonden van Valen, L.J. 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) van Valen, L. J. (2019). In God verbonden: De gereformeerde vroomheidsbetrekkingen tussen Schotland en de Nederlanden in de zeventiende eeuw, met name in de periode na de Restauratie (1660-1700). Labarum Academic. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Hoofdstuk 7 Tweezijdige puriteinse vroomheid Karakter van het Schots Puritanisme en parallellen tussen de Schotse Tweede Reformatie en de Nadere Reformatie Met de publicatie van ‘Christus de Weg, de Waarheid en het Leven’ komt ook naar voren dat deze heldere denker op het gebied van de kerkregering, deze bekwame en voorzichtige theoloog, deze ernstige en heftige polemist, een prediker en devotionele schrijver kon zijn met zulk een kracht en diepe spiritu- aliteit.1 I.B. -

Donald Macleod, "Scottish Calvinism: a Dark, Repressive Force?" Scottish Bulletin of Evangelical Theology 19.2 (Autumn

SCOTTISH CALVINISM: A DARK, REPRESSIVE FORCE? 00NALD MACLEOD, PRINCIPAL, FREE CHURCH COLLEGE, EDINBURGH INTRODUCTION 'Scottish Calvinism has been a dark, repressive force.' The thesis is a common one; almost, indeed, an axiom. Few seem to realise, however, that the thesis cannot be true without its corollary: the Scots are a repressed people, lacking the confidence to express themselves and living in fear of their sixteenth-century Super Ego. The corollary, in turn, immediately faces a paradox. Scotland has never been frightened to criticise Calvinism. This is particularly true of our national literature. John Knox has been the object of relentless opprobrium, the Covenanters have been pilloried as epitomes of bigotry and intolerance, Thomas Boston portrayed as a moron, the Seceders as kill joys and Wee Frees as antinomian Thought Police. The phenomenon is unparalleled in the literature of any other part of the United Kingdom. There has been no comparable English assault on Anglicanism. Nor has there been a similar Irish critique of Catholicism. Scotland has been unique in the ferocity with which its literature has turned on its religion. The Kirk's brood may have been rebellious. They have certainly not been repressed. DETRACTORS The most influential detractor was, of course, Waiter Scott, whose heroic, well-rounded Cavaliers and Jacobites contrast vividly with his narrow, bigoted Presbyterians and Covenanters. But Scott was not the first. Robert Burns had already set the agenda. In Holy Willie 's Prayer, for example, he stereotypes and lampoons the 'typical' Calvinist elder, famed only for his polemical cant, tippling orthodoxy and blind hypocrisy. His God, Sends ane to heaven an' ten to hell A' for thy glory! And no for ony gude or ill they've done afore thee. -

The Bulwark Magazine of the Scottish Reformation Society

The Bulwark Magazine of the Scottish Reformation Society OCT - DEC 2012 // £1 October - December 2012 1 The Bulwark The Gospel in Magazine of the Scottish Reformation Society The Magdalen Chapel 41 Cowgate, Edinburgh, EH1 1JR Tel: 013 1220 1450 Caithness: Part 2 Email: [email protected] www.scottishreformationsociety.org.uk Registered charity: SC007755 John Smith Chairman Committee Members The previous article outlined the progress of the gospel in the Far North from the » Rev Dr S James Millar » Mr Norman Fleming Reformation until the times of revival under the preaching of Rev. Alexander Gunn of Vice-chairman » Watten in the nineteenth century. In this second part we look at the contribution of » Rev Maurice Roberts Rev John J Murray some other prominent Caithness ministers during the nineteenth century. » Rev Kenneth Macdonald Secretary » Rev Douglas Somerset » Mr James Dickson Treasurer » Mr Allan McCulloch I. JOHN MUNRO OF HALKIRK had an unshakeable assurance of faith, » Rev Andrew Coghill (1768-1847) founded upon his view of Christ as “He who had never lost, and never would lose a John Munro was born in the parish of battle”. On one occasion, John Munro was CO-OPERATION OBJECTS OF THE SOCIETY Kiltearn in Ross-shire and was the great discussing the nature of saving faith with Rev In pursuance of its objects, the Society may co- (a) To propagate the evangelical Protestant grandson of John Munro “Caird”, the friend W. R. Taylor, a learned theologian who easily faith and those principles held in common by operate with Churches and with other Societies those Churches and organisations adhering to of Thomas Hog the Covenanter. -

Testimony of James Skene Dec 1680

‘The last testimony to the cause and interest of Christ from Ja[mes]: Skeen, brother to the late Laird of Skeen, being close prisoner in Edinburgh for the same. To all and sundry professors in the South, especially Mr Ro[ber]t. M’Waird, in Holland, Mr Tho[mas]. Hog, Mr Archibald Riddell, Mr Alexander Hasty, preachers, who now have mad defection by loving their quiet so much, and so complying fully with the stated enemys of Jesus, fearing the offending of them who ar pretended magstrats. Dear Freinds,—The Lord, in his holy wisdome for trying and purging of a people for himselfe, is as permited the dovill raise the kingdom of Antichrist to a dreadfull hight, so that in these sad trying times many ar impudently bold to deny their master. Of nonconformists ministers, not only these who have taken leicence from the usurpers of our Lord’s croun and so becom indulged ministers, by which means they acknowled a tirrant on the thron to be head of the Church, which properly belongeth to our Lord Jesus Christ, as Psal. 2. 8, Ephes. 1. 22; but also there ar of minister that say a confedaracy with them, that consult to banishe quite our blesed Lord of Scotland, by sheding the blood of the saints and making armed forces presecute and bear doun the Gospell ordinances in the feilds. For after Bothweell [in June, 1679,] many ar gaping for indulgence, and all the whole ministers are content to be ordered by the enemies of Christ and to keep only house conventicles; and, in short, there is not a feild conventicle in all Scotland. -

Charter Chest of the Earldom of Wigtown

SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY CHARTER CHEST OF THE EARLDOM OF WIGTOWN, EDITED BY FRANCIS J. GRANT, W.S. ROTHESAY HERALD. EDINBURGH: PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY JAMES SKINNER & COMPANY 1910. BDINBORGH ! PRINTED BT JillES SXINNER AND OOKPAKY~ PREF ACE. THE Inventory of the contents of the Charter Chest of the Earldom of ,vigtown, from which the following is now printed, was drawn up in the year 1681 on the succession John, 6th Earl of Wigtown, who succeeded his father, \Yilliam,. 5th Earl, on his death on 8th April 1681. The volume which originally had belonged to Thomas Hill of the Register of Sasines, Glasgow, was latterly in the possession of the late Sir William Fraser, Deputy Keeper of the Records, and was presented to the Library of the Lyon Office by his 'frustees. The writs, many of which are of great historical interest, the family of Fleming having always been closely associated with the Royal Family, date from the year 1214 onwards, and relate to lands in the counties of Aberdeen, Ayr, Dumba~on, Forfar, Haddington, Lanark, Peebles, Perth, Renfrew, Roxburgh, Selkirk, Stirling and Wigtown, as well as to the offices of Great Chamberlain of Scotland, Usher of the King's Household and the Sheriffships of Dun1barton, Peebles and Roxburgh. Some of these documents have been printed in various works, and reference is made to Hunter's Biggar and the House of Fleming, Antiquities of Aberdeen and Banff, Holyrood Charters, Crawfurd's Peerage, Spalding Club Miscellany, &c., where they will be found. CHARTER CHEST OF THE EARLDOM OF WIGT(lWN. I-INVENTORY of the Writs and Evidents of the Lands and Barony of Lenzie, Lands of Cumbernauld and Others. -

The Bass Rock

The Bass Rock. OAviO J l««,oi~, AT lf<<.M fJXA\ ^^ fiSli - t —____ k« . CHAPTER I. GENERAL DESCRIPTION. HE rocky islands that dot the shores of the Forth have been picturesquely described by Sir Walter Scott in " Marmion " as " emeralds chased in gold." They have also been described as " bleak islets." Both these seemingly contradictory descriptions are true according as the sky is bright and sunny or, as so often happens in our northern climate, cloudy and1 overcast. Of these islands those known as the greater *' emeralds " are Inchkeith, Inchcolme, May Island, and the Bass. The lesser " emeralds " being Cramond, Inch- garvie, Fidra, Eyebroughty, and Craig Leith. Over nearly all these islands there clings a halo of romance and legend. With Inchkeith we associate a gallant chieftain, of the name of Keith, who in one of the« invasions of the Danes slew their leader, and received the island as a reward from a grateful King. 4 THE BASS ROCK. Inchcolme takes us back to the time of the Britons when the Druids are said to have here practised the mysteries of their religion. It was here, too, that David I., having sought refuge in a storm, was enter- tained by the hermit, and afterwards in gratitude founded a monastery, the ruins of which form at the present day a picturesque feature of the island. The May Island in early Christian times was dedi- cated to religious uses, and here a colony of monks under the saintly Adrian were massacred by the Danes. The beautifully shaped Fidra has also its historical associations, having had a monastic establishment in con- nection with the Abbey at North Berwick, and also a castle called Tarbert, which at one time belonged to the Lauders of the Bass. -

Download Download

CONTENTS OF APPENDIX. Page I. List of Members of the Society from 1831 to 1851:— I. List of Fellows of the Society,.................................................. 1 II. List of Honorary Members....................................................... 8 III. List of Corresponding Members, ............................................. 9 II. List of Communications read at Meetings of the Society, from 1831 to 1851,............................................................... 13 III. Listofthe Office-Bearers from 1831 to 1851,........................... 51 IV. Index to the Names of Donors............................................... 53 V. Index to the Names of Literary Contributors............................. 59 I. LISTS OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF THE ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. MDCCCXXXL—MDCCCLI. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN, PATRON. No. I.—LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. (Continued from the AppenHix to Vol. III. p. 15.) 1831. Jan. 24. ALEXANDER LOGAN, Esq., London. Feb. 14. JOHN STEWARD WOOD, Esq. 28. JAMES NAIRWE of Claremont, Esq., Writer to the Signet. Mar. 14. ONESEPHORUS TYNDAL BRUCE of Falkland, Esq. WILLIAM SMITH, Esq., late Lord Provost of Glasgow. Rev. JAMES CHAPMAN, Chaplain, Edinburgh Castle. April 11. ALEXANDER WELLESLEY LEITH, Esq., Advocate.1 WILLIAM DAUNEY, Esq., Advocate. JOHN ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL, Esq., Writer to the Signet. May 23. THOMAS HOG, Esq.2 1832. Jan. 9. BINDON BLOOD of Cranachar, Esq., Ireland. JOHN BLACK GRACIE, Esq.. Writer to the Signet. 23. Rev. JOHN REID OMOND, Minister of Monfcie. Feb. 27. THOMAS HAMILTON, Esq., Rydal. Mar. 12. GEORGE RITCHIE KINLOCH, Esq.3 26. ANDREW DUN, Esq., Writer to the Signet. April 9. JAMES USHER, Esq., Writer to the Signet.* May 21. WILLIAM MAULE, Esq. 1 Afterwards Sir Alexander W. Leith, Bart. " 4 Election cancelled. 3 Resigned. VOL. IV.—APP. A 2 LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. -

JAMES FRASER, LAIRD of BREA —Probed Many Hearts, Beginning with His Own

A LEX AN i:)EF< ‘Dr. Whyte has at last written his “Life of Christ.”’— Expository Times. Large Crown 87jo. Price 35. bd. net. THE WALK, CONVERSATION AND CHARACTER OF JESUS CHRIST OUR LORD ‘ Dr. Alexander Whyte’s book commands, like all its writer’s works, the attention of the reader. The author has great dramatic power, and a marked felicity of expression. Dr. Whyte uses the imagery, and even some of the catchwords, of a Calvinism of the past ; but he manages to put new life into them, and to show, sometimes with startling clearness, the lasting truth within the perishable formula.’—Spectator. ‘ It is distinguished by the exegetical and literary qualities that characterise all Dr. Whyte’s writings. His preaching is always intensely earnest, it is thoroughly evangelical, and Dr. Whyte never fails to enforce its lessons by illustrations drawn from his everyday experience, whether in the study or in pastoral visitation.’—Scotsman. ‘ Will rank with every competent judge of Dr. Whyte’s expositions as his very best book. It represents Dr. Whyte at his best. It is practically a life of Christ—and it is that life on its inner side. The titles of the lectures are expressed in a characteristic way, and the treatment of the subject is fresh and original in every case.’—Christian Leader. JAMES FRASER, LAIRD OF BREA —Probed many hearts, beginning with his own. Yea, this man’s brow, like to a title-leaf, Foretells the nature of a tragic volume: Thou tremblest, and the whiteness in thy cheek Is apter than thy tongue to tell thine errand.