The Covenanters in Moray and Ross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

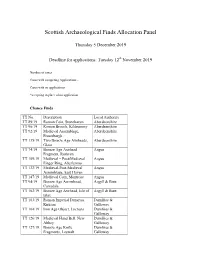

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel Thursday 5 December 2019 Deadline for applications: Tuesday 12th November 2019 Number of cases – Cases with competing Applications - Cases with no applications – *accepting in place of no application Chance Finds TT No. Description Local Authority TT 89/19 Roman Coin, Stonehaven Aberdeenshire TT 90/19 Roman Brooch, Kildrummy Aberdeenshire TT 92/19 Medieval Assemblage, Aberdeenshire Fraserburgh TT 135/19 Two Bronze Age Axeheads, Aberdeenshire Glass TT 74/19 Bronze Age Axehead Angus Fragment, Ruthven TT 109/19 Medieval – Post-Medieval Angus Finger Ring, Aberlemno TT 132/19 Medieval-Post-Medieval Angus Assemblage, East Haven TT 147/19 Medieval Coin, Montrose Angus TT 94/19 Bronze Age Arrowhead, Argyll & Bute Carradale TT 102/19 Bronze Age Axehead, Isle of Argyll & Bute Islay TT 103/19 Roman Imperial Denarius, Dumfries & Kirkton Galloway TT 104/19 Iron Age Object, Lochans Dumfries & Galloway TT 126/19 Medieval Hand Bell, New Dumfries & Abbey Galloway TT 127/19 Bronze Age Knife Dumfries & Fragments, Leswalt Galloway TT 146/19 Iron Age/Roman Brooch, Falkirk Stenhousemuir TT 79/19 Medieval Mount, Newburgh Fife TT 81/19 Late Bronze Age Socketed Fife Gouge, Aberdour TT 99/19 Early Medieval Coin, Fife Lindores TT 100/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Fife St Andrews TT 101/19 Late Medieval/Post-Medieval Fife Seal Matrix, St Andrews TT 111/19 Iron Age Button and Loop Fife Fastener, Kingsbarns TT 128/19 Bronze Age Spearhead Fife Fragment, Lindores TT 112/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Highland Muir of Ord TT -

St John the Evangelist Scottish Episcopal Church

St John the Evangelist Scottish Episcopal Church Forres General Data Protection Compliance Statement St John’s Forres is an incumbency within the Scottish Episcopal Church. It is established exclusively for charitable purposes, primarily for the advancement of religion and to provide public benefit. (The expression “charitable purposes” shall mean a charitable purpose as defined in section 7 of the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005 as amended from time to time (“the 2005 Act”) which is also regarded as a charitable purpose in relation to the application of the Taxes Acts from time to time in force.) In order to progress its charitable purposes, the Clergy and Vestry of St John’s Forres collects and processes information from congregation members on the legal basis of informed consent. This information supports the following activities: 1. Pastoral care for the congregation 2. Financial security for the incumbency, its employees and its assets 3. Charitable giving 4. Communication with congregation members about the worship pattern and other activities of the church. 5. Enabling St John’s to provide a voluntary service for the benefit of the wider community. Vestry is responsible for the privacy, security, retention of this information within legal limits, and destruction/deletion of the same when appropriate. It undertakes to audit this information and to assess for risk on an annual basis, to enable subject access appropriately if so requested, and to ensure that congregation members are made aware of exactly what use is intended from the information which is requested and processed. Sharing of your data Your personal data is confidential and will be shared only as set out here. -

Karen Helm (March 4, 2006) Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar June Hanley (March 29, 2008)

Tunes Played at Piobaireachd Society of Central Pennsylvania Meetings The Battle of Auldearn (Setting #1) Karen Helm (March 4, 2006) Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar June Hanley (March 29, 2008) The Battle of the Pass of Crieff Dan Lyden (April 14, 2018) Beloved Scotland Adam Green (June 18, 2006) Karen Helm (November 3, 2007) – Urlar The Big Spree Thompson McConnell (January 13, 2018) Cabar Feidh Gu Brath Michael Philbin (March 29, 2008) Thompson McConnell (April 14, 2018) Catherine’s Lament Rory McConnell (December 2, 2018) The Cave of Gold Thompson McConnell (November 3, 2007) Thompson McConnell (March 29, 2008) Thompson McConnell (November 30, 2008) Thompson McConnell (March 6, 2010) Thompson McConnell (February 24, 2018) Chisholm’s Salute Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar Ceol Na Mara (Song of the Sea) Laura Neville (March 4, 2018) Clan Campbell’s Gathering Daniel Emery (December 2, 2006) Karen Helm (November 3, 2007) Karen Helm (December 1, 2007) Karen Helm (February 23, 2008) Ken Campbell (March 4, 2018) Daniel Emery (April 8, 2018) The Clan MacNab’s Salute David Bailiff (December 1, 2007) Colin MacRae of Invereenat’s Lament Ken Campbell (January 21, 2006) – Urlar & Variations I & II Marty McKeon (November 3, 2007) Tom Miller (November 30, 2008) Gustav Person (January 13, 2018) Gustav Person (March 4, 2018) The Company’s Lament Patrick Regan (December 2, 2006) Corrienessan’s Salute Tom Miller (January 3, 2009) – Urlar Matt Davis (April 14, 2018) Rory McConnell (December 2, 2018) Cronan Corrievrechan -

Site Selection Document: Summary of the Scientific Case for Site Selection

West Coast of the Outer Hebrides Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) No. UK9020319 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Scotland Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed in preparation for possible formal Scotland consultation. 30/06/15 Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Updated with minor amendments to address Marine comments from Marine Scotland Science in Scotland preparation for the SPA stakeholder workshop. 23/02/16 Emma Philip Version 4 Revised format, using West Coast of Outer MPA Hebrides as a template, to address comments Project received at the SPA stakeholder workshop. Steering Emma Philip Group 07/04/16 Version 5 Text updated to reflect proposed level of detail for Marine final versions. Scotland Emma Philip 18/04/16 Version 6 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Glen Tyler & Emma Philip 19/06/16 Version 7 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 20/6/16 Version 8 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 9 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 2. Site summary ..................................................................................................... 2 3. Bird survey information .................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines ................................. 7 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................ 13 6. Information on qualifying species ................................................................. -

Hunter Bailey Phd Thesis 08.Pdf (1.357Mb)

VIA MEDIA ALIA: RECONSIDERING THE CONTROVERSIAL DOCTRINE OF UNIVERSAL REDEMPTION IN THE THEOLOGY OF JAMES FRASER OF BREA (1639-1699) A thesis submitted to New College, the School of Divinity of the University of Edinburgh in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2008 By Hunter M. Bailey M.Th. (2003) University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK M.Div. (2002) Reformed Theological Seminary, Jackson, MS, USA B.A. (1998) University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA I hereby declare that this thesis has been composed by myself and is the result of my own independent research. It has not, in any form, been submitted or accepted for any other degree or professional qualification, as specified in the regulations of the University of Edinburgh. All quotations in this thesis have been distinguished by quotation marks, and all sources of outside information have received proper acknowledgment. _________________________________ Hunter M. Bailey 16 June 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents....................................................................................................... i Acknowledgements.................................................................................................... v Abstract..................................................................................................................... vii Abbreviations............................................................................................................ ix Section A Chapter 1: An Introduction.......................................................................... -

The Register of Marriages for the Parish Of

6c 941.0004 Sco87s Ga M.L 941.0004 Scq87s 1403849 GENEALOGY COLLECTION ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBBARY 3 1833 00676 3558 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/registerofmarria32edin yf/ky PART XXXII. 1403849 I595-I 700.] Edinburgh Marriage Register. 401 /' >JLawson (Lasone, Lasoun, Lausone, Lawsoun), John, smith Isobel Bruce 7 July 1670 John, stabler ; Elizabeth Nicoll, married be Mr John M 'Queen I Feb. 679 Peacock 2 668 John, tailor ; Janet July tailor Cook June 670 John, ; Jean 24 John ; Margaret Nicolson, married by Mr. Alexander Malcome 10 Aug. 682 John ; Isobel Tasker, by Mr. Burgess in the S. K. 24 Dec. 689 Katherine ; Patrick M'Nacht, skinner 8 Dec. 602 Katharine ; Mr. Archibald Borthwick 29 Dec. 700 Foster, merchant Margaret ; John 13 June 599 Margaret ; Thomas Wylie, bonnet-maker 5 Sept. 601 Margaret; John Rantoun 13 Nov. 605 Symsoun, gentleman t. 18 Sept. 610 Margaret ; Job Margaret ; Andrew Lasone, chopman 29 Aug. 616 Margaret ; Walter Scotte, tailor 5 Sept. 628 Margaret ; Andrew Hepburne, tailor 14 Feb. 640 Margaret Andersone, steward to Craigmillar 10 May 642 ; John Margaret ; Robert Crombie, bookseller 22 Sept. 642 Margaret ; William Johnstoun, porter at Heriot's Hospital 6 May 651 Margaret ; Thomas Noble, skinner 23 Apr 672 I Margaret ; George Broun, baker 28 Mar. 679 Margaret ; Robert Wilson, glover 1 1 Jan. 692 Grive 8 May Margaret ; John 698 Marion ; Baillie Matthew 30 May 604 Marion ; Alexander Pringle, cordiner 13 Aug. 612 Marion ; William Liddale, wright 27 Jan. 665 Marion Angus, flesher 16 Sept. -

Exteacts from the Peesbytbry Eecords of Dalkeith, Relating to the Parish of Newbattle, During the In- Cumbency of Mr Robert Leig

IV. EXTEACTS FROM THE PEESBYTBRY EECORDS OF DALKEITH, RELATING TO THE PARISH OF NEWBATTLE, DURING THE IN- CUMBENC ROBERR M F YO T LEIGHTON, 1641-1663. COMMUNICATED BY THE REV. THOMAS GORDON, MINISTEE OF NEWBATTLE. WITH SOME INTRODUCTORY REMARKS BY DAVID LAING, ESQ., V.P. y attempAn o discovet t factw ne rs regardin a persoe liff th o ge n o wels l o justlknows d ynan admire s ARCHBISHOa d P LEIOHTON, might seem to be hopeless. Yet the earlier part of his history remains very obscure, and, in particular, his connexion with the Presbyterian Church durin e Covenane timegth th f o s almoss ha t t been wholly overlookeds a , perhaps s admirersomhi f eo s could wish t shouli . Anythingdbe , how- ever, tendin illustrato gt e characteeth cannon f suco ma r ha e t b fai o t l interesting. For this purpose I had intended to form a small collection of Leighton's unpublished letters, writte t variouna s period lifes t finhi bu d, f sthao I t have been forestalled, partly by some communications which have lately appeared in " Notes and Queries," from the Eev. C. F. Secretan, Besborough Gardens, Westminster, who has brought together fifteen such unpublished letters, chiefly from the Lauderdale Correspondence, now Britise inth h Museum. The extracts from the presbytery books of Dalkeith, which I have now befory t ola e Society th e , were obligingly communicate e Eevth .y b d THOMAS GORDON, minister of Newbattle. They furnish a number of minute notices regarding the period of Leighton's career, not much knowEngliss hi o t nh biographers e ministeth s , whef thawa o r e th n paris thed h an ;y server GordoM s remarkes a , nha s lettehi n dri accom- panying the extracts, to correct various mistakes into which Bishop Burnet falles misleha d nan d later writers followine Th . -

Old West Kirk of Greenock 15911591----18981898

The Story of The Old West Kirk Of Greenock 15911591----18981898 by Ninian Hill Greenock James McKelvie & Sons 1898 TO THE MEMORY OF CAPTAIN CHARLES M'BRIDE AND 22 OFFICERS AND MEN OF MY SHIP THE "ATALANTA” OF GREENOCK, 1,693 TONS REGISTER , WHO PERISHED OFF ALSEYA BAY , OREGON , ON THE 17TH NOVEMBER , 1898, WHILE THESE PAGES ARE GOING THROUGH THE PRESS , I DEDICATE THIS VOLUME IN MUCH SORROW , ADMIRATION , AND RESPECT . NINIAN HILL. PREFACE. My object in issuing this volume is to present in a handy form the various matters of interest clustering around the only historic building in our midst, and thereby to endeavour to supply the want, which has sometimes been expressed, of a guide book to the Old West Kirk. In doing so I have not thought it necessary to burden my story with continual references to authorities, but I desire to acknowledge here my indebtedness to the histories of Crawfurd, Weir, and Mr. George Williamson. My heartiest thanks are due to many friends for the assistance and information they have so readily given me, and specially to the Rev. William Wilson, Bailie John Black, Councillor A. J. Black, Captain William Orr, Messrs. James Black, John P. Fyfe, John Jamieson, and Allan Park Paton. NINIAN HILL. 57 Union Street, November, 1898. The Story of The Old West Kirk The Church In a quiet corner at the foot of Nicholson Street, out of sight and mind of the busy throng that passes along the main street of our town, hidden amidst high tenements and warehouses, and overshadowed at times by a great steamship building in the adjoining yard, is to be found the Old West Kirk. -

Traditions of the Macaulays of Lewis. 367

.TRADITION THF SO E MACAULAY3 36 LEWISF SO . VII. TRADITION E MACAULAYTH F SO . LEWISF L SO . CAPTY W B . .F . THOMAS, R.N., F.S.A. SCOT. INTRODUCTION. Clae Th n Aulay phonetia , c spellin e Gaelith f go c Claim Amhlaeibli, takes its name from Amhlaebh, which is the Gaelic form of the Scandinavian 6ldfr; in Anglo-Saxon written Auluf, and in English Olave, Olay, Ola.1 There are thirty Olafar registered in the Icelandic Land-book, and, the name having been introduce e Northmeth e y Irishdb th o t n, there ear thirty-five noticed in the " Annals of the Four Masters."2 11te 12td th han hn I centuries, when surnames originatet no thef i , d ydi , were at least becoming more general, the original source of a name is, in the west of Scotland, no proof of race ; or rather, between the purely Norse colony in Shetland and the Orkneys, and the Gael in Scotland and Ireland, there had arisen a mixture of the two peoples who were appropriately called Gall-Gael, equivalen o sayint t g they were Norse-Celt r Celtio s c Northmen. Thus, Gille-Brighde (Gaelic) is succeeded by Somerled (Norse); of the five sons of the latter, two, Malcolm and Angus, have Gaelic names havo tw ;e Norse, Reginal fifte th Olafd h d an bear an ; sa Gaelic name, Dubhgall,3 which implies that the bearer is a Dane. Even in sone th Orknef Havar sf o o o Hakoe ydtw ar Thorsteind n an e thirth t d bu , is Dufniall, i.e., Donald.4 Of the Icelandic settlers, Becan (Gaelic) may 1 " Olafr," m. -

The Scottish Book of Common Prayer, 1637

The Scottish Book of Common Prayer, 1637 5 The Scottish Book of Common Prayer, 1637. " THE Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and other parts of Divine Service for the use of the Church of Scotland " owes its origin to Charles I., who wished to see one form of worship used throughout his dominions. Uniformity of worship was one of the desires of the earlier Covenanters, so that in this at least the monarch and his opponents were at one. When Charles came to Scotland for his coronation in 1633, he was accompanied by Archbishop Laud, and it is on record that the Anglican Book of Common Prayer was then publicly read in all the churches where the royal party worshipped. No scruple was made regarding its use in churches frequented by the Scots in England, and these things may explain why both the King and the Archbishop thought that there would be little difficulty in getting their wishes carried into effect here. The first idea was simply to have the English book, as it stood, substituted for the Book of Common Order then in general use. The Scots Bishops were against this, thinking that, if new forms were to be introduced, these should be different from the English ones, lest it should be thought that the church of the smaller nation was being subordinated to that of the larger. The majority, both of Bishops and Ministers, would probably have preferred that any alterations of the Book of Common Prayer should be in a Puritan direction. Such a book had been drawn up some twenty years earlier by William Cowper, Bishop of Galloway, assisted by some of the " most learned and grave ministers " of the Church of Scotland. -

History of the Mathesons, with Genealogies of the Various Branches

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/historyofmathesOOmack HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS. This Edition is limited to— Small Paper JfiO Copies. Large „ 50 PRINTED BY WILLIAM MACKAY, 27 HIGH STREET, INVERNESS. : HISTOKT OF THE MATHESONS WITH Genealogies of the Various Faailies BY ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A. (Scot.) THE CLAN HISTORIAN. SECOND EDITION. EDITED, LARGELY RE-WRITTEN, AND ADDED TO BY ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., AUTHOR OF " AN ETYMOLOGICAL DICTIONARY OF THE GAELIC LANGUAGE." Stirling : ENEAS MACKAY, 43 Murray Place. Xonoon GIBBINGS & COY., LTD., 18 Bury Street, w.c. 190 0. TO Sir KENNETH MATHESON, Bart. OF LOCHALSH, A WORTHY REPRESENTATIVE OF ONE OF THE MOST CAPABLE, BRAVE, AND STALWART OF HIGHLAND FAMILIES. PREFACE. The first edition of the late Mr Mackenzie's "History of the Mathesons" appeared in 1882, and the book has now been long out of print. Mr Mackenzie had a difficult task in writing this work, for though the Clan in the 14th century undoubtedly rivalled in position and power the neighbouring Mackenzies, yet through the action of the Macdonalds in the following century its unity was broken, and it became a " minor clan," with no charters, and with no references thereto in public documents. The individual history of the Northern Clans at best begins with the 15th century, but here Mr Mackenzie had only the clan traditions to avail himself of until the 17th century, when the minor clans all over the North come into the light of history from under the shadow of the larger clans and their chiefs.