1.2 Textile Fibres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Term Loading and Additional Material Properties of Vectran Fabric for Inflatable Structure Applications

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2010 Long Term Loading and Additional Material Properties of Vectran Fabric for Inflatable Structure Applications Timothy L. Weadon Jr. West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Weadon, Timothy L. Jr., "Long Term Loading and Additional Material Properties of Vectran Fabric for Inflatable Structure Applications" (2010). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4669. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4669 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Term Loading and Additional Material Properties of Vectran Fabric for Inflatable Structure Applications Timothy L Weadon, Jr Thesis submitted to the College of Engineering and Mineral Resources at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements -

Optimisation of the Warp Yarn Tension on a Warp Knitting Machine

AUTEX Research Journal, Vol. 12, No2, June 2012 © AUTEX OPTIMISATION OF THE WARP YARN TENSION ON A WARP KNITTING MACHINE Vivienne Pohlen, Andreas Schnabel, Florian Neumann, Thomas Gries Institut für Textiltechnik der RWTH Aachen University, Germany Otto-Blumenthal-Str. 1, D-52074 Aachen, Phone: +49 (0)241 80 23462, Fax: +49 (0)241 80 22422, E-Mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Investigations (calculations) based on a warp yarn tension analysis on a warp knitting machine with multiaxial weft yarn insertion allow prospective reduced yarn tension differences in technical warp knits. From this a future opportunity is provided to substitute the subjective warp let-off adjustment by a model of tension control. The outcome of this is a higher reproducibility with associated increasing process reliability and rising product quality. Key words: Multiaxial fabric, non-crimp fabric (NCF), warp knitting machine, warp yarn tension, yarn tension control. Initial situation warp knitted glass or carbon fibre layers. These are made on warp knitting machines with multiaxial weft insertion. These Increasing political pressure is demanding that industry now enable the production of NCFs for different applications by always produces environmentally sound products. The adjusting several parameters. automobile sector is developing more powerful, lighter electric vehicles (e.g. Megacity Vehicle, MCV). The MCV of BMW in A detailed study regarding various adjustable parameters on cooperation with SGL Automotive Carbon Fibers is based upon such a machine has not occurred in previous works. A basis a composite construction of steel, aluminium, and CFRP for this is provided by warp tension studies on conventional (carbon fibre reinforced plastic) of 40% [1]. -

A Perspective on High-Performance CNT Fibres for Structural Composites

A Perspective on High-performance CNT fibres for Structural Composites Anastasiia Mikhalchan, Juan José Vilatela IMDEA Materials Institute, C/Eric Kandel 2, Getafe, Madrid, Spain, 28906 This review summarizes progress on structural composites with carbon nanotube (CNT) fibres. It starts by analyzing their development towards a macroscopic ensemble of elongated and aligned crystalline domains alongside the evolution of the structure of traditional high- performance fibres. Literature on tensile properties suggests that there are two emerging grades: highly aligned fibres spun from liquid crystalline solutions, with high modulus (160 GPa/SG) and strength (1.6 GPa/SG), and spun from aerogels of ultra-long nanotubes, combining high strength and fracture energy (up to 100J/g). The fabrication of large unidirectional fabrics with similar properties as the fibres is presently a challenge, which CNT alignment remaining a key factor. A promising approach is to produce fabrics directly from aerogel filaments without having to densify and handle individual CNT fibres. Structural composites of CNT fibres have reached longitudinal properties of about 1 GPa strength and 140 GPa modulus, however, on relatively small samples. In general, there is need to demonstrate fabrication of large CNT fibre laminate composites using standard fabrication routes and to study longitudinal and transverse mechanical properties in tension and compression. Complementary areas of development are interlaminar reinforcement Corresponding Author. E-mail: [email protected] (Anastasiia Mikhalchan) Corresponding Author. E-mail: [email protected] (Juan José Vilatela) 1 with CNT fabric interleaves, and multifunctional structural composites with energy storage or harvesting functions. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1. State-of-the-art of CNT fibres 5 1.1 Synthesis and hierarchical structure of CNT fibres 5 1.2 Mechanical properties of CNT fibres 8 1.3 Historical retrospective on R&D of commercial high-performance fibres and CNT 11 fibres PART 2. -

Formulating Equations for Warp Knitted Structures (Fabrics) Notations Design Area

Published by : International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) http://www.ijert.org ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 5 Issue 03, March-2016 Formulating Equations for Warp Knitted Structures (Fabrics) Notations Design Area Dereje Berihun Sitotaw Textile Engineering Ethiopian institute of Textile and Fashion Technology, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia Abstract— this formula is developed to solve the problems In warp knitting the fabric is produced by the developments of repeated mistakes during the notations of warp knitted of lap instead of loop in weft knitting for it is formed by structures. Notation of warp knitted fabrics is not easy lapping movement of warp yarn guide. The lappings are two like that of weft knitted fabrics. The degree of shifting, types depending of the movement of guide bar with yarn design areas, numbers of overlaps are the main things relative to needle surface and termed as overlap and considered during warp knitted fabrics designing. The underlap. Overlap is the lateral movement of the guide bars formula was developed by considering degree of wale on the beard or hook side of the needle. This movement is shift and number of overlaps in one line in the knitted normally restricted to one needle space. Underlap is the fabrics/structure. The formula will help warp knit lateral movement of the guide bars on the side of the needle designers particularly for those designing without remote from the hook or beard. This movement is limited software. The formulation was done by analyzing only by the mechanical considerations. It is the connection different types of warp knit structures. -

KNITTING Definition Statement Relationship Between Large Subject

D04B KNITTING Definition statement This subclass/group covers: weft knitting machines are covered by D04B 7/00 to D04B 13/00, details of, or auxiliary devices incorporated in such machines are covered by D04B 15/00 and articles made by such machines are covered by D04B 1/00 warp knitting machines are covered by D04B 23/00 to D04B 25/00, details of, or auxiliary devices incorporated in such machines are covered by D04B 27/00 and articles made by such machines are covered by D04B 21/00 details of, or auxiliary devices incorporated in knitting machines not limited to a specific kind of knitting machine are covered by D04B 35/00 miscellaneous knitting machines and articles made by such machines are covered by D04B 39/00 hand knitting equipment is covered by D04B 3/00, D04B 5/00 and D04B 33/00 auxiliary apparatuses or devices for use with knitting machines are covered by D04B 37/00 or for hand knitting equipment are covered by D04B 17/00, D04B 19/00 and D04B 31/00 Relationship between large subject matter areas The difference between the subclass D04B and B32B5 is as follows:layered products including knitted products as such should be classified in B32B5 only; layered products formed by a knitting process featuring specified patterns or information on the composition of the knit article should be classified in D04B. Note that such products may comprise additional coated faces. References relevant to classification in this subclass This subclass/group does not cover: Layered products (i.e. laminates) B32B 5/00 including knitted articles 1 Knitted products of unspecified A41A61F structure or composition, e.g. -

Textile Design: a Suggested Program Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME CI 003 141 ED 102 409 95 Program Guide.Fashion TITLE Textile Design: A Suggested Industry Series No. 3. Fashion Inst. of Tech.,New York, N.T. INSTITUTION Education SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Adult,Vocational, and Technictl (DREW /OE), Washington,D.C. PUB DATE 73 in Fashion Industry NOTE 121p.; For other documents Series, see CB 003139-142 and CB 003 621 Printing AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents,U.S. Government Office, Washington, D.C.20402 EDRS PRICE NP -$0.76 HC-$5.70 PLUS POSTAGE Behavioral Objectives; DESCRIPTORS Adult, Vocational Education; Career Ladders; *CurriculumGuides; *Design; Design Crafts; EducationalEquipment; Employment Opportunities; InstructionalMaterials; *Job Training; Needle Trades;*Occupational Rome Economics; OccupationalInformation; Program Development; ResourceGuides; Resource Units; Secondary Education;Skill Development;*Textiles Instruction IDENTIFIERS *Fashion Industry ABSTRACT The textile designguide is the third of aseries of resource guidesencompassing the various five interrelated program guide is disensions of the fashionindustry. The job-preparatory conceived to provide youthand adults withintensive preparation for and also with careeradvancement initial entry esploysent jobs within the textile opportunities withinspecific categories of provides an overviewof the textiledesign field, industry. The guide required of workers. It occupational opportunities,and cospetencies contains outlines of areasof instruction whichinclude objectives to suggestions for learning be achieved,teaching -

Industrial Fabric Yarn Fibers Processes Products

MOVING HIGH PERFORMANCE FIBERS FORWARD INDUSTRIAL FABRIC YARN FIBERS PROCESSES PRODUCTS WHY FIBER-LINE®FIBER INDUSTRIAL OPTICAL FABRIC CABLES YARN? Key Features Overview • Available Flat or Twisted • FIBER-LINE®’s offering of Industrial Fabric Yarn are utilized in a wide • Material can be “Rolled flat” to remove range of applications. FIBER-LINE®’s marriage of high-performance false or producers’ twist fibers and additional processing create unique products that extend • Metered lengths and various spool sizes the life of our customer’s end use product. available • Our yarn have been processed in a variety of different ways utilizing: Knitting, weaving, braiding. FIBER-LINE® FIBERS FOR INDUSTRIAL FABRIC YARN Packaging • Kevlar® Para-Aramid FIBER-LINE® Industrial Fabric Yarn are supplied on a variety of card- • Nomex® Meta-Aramid board tubes to meet your equipment needs. Contact us today • Vectran® Liquid Crystal Polymer (LCP) with tube dimensions you require. Packages can be supplied on colored, • Carbon Fiber embossed and/or slit tubes. Plastic or metal reels are also available. • Fiberglass • Technora® FIBER-LINE® PERFORMANCE ADDING COATINGS • FIBER-LINE® Colorcoat™: Vibrant Colors for Aesthetic Applications • FIBER-LINE® Wearcoat™: Abrasion & High-Temperature Resistance • FIBER-LINE® Bondcoat™: Adhesion Promotion • FIBER-LINE® Repelcoat™: Water Repellancy • FIBER-LINE® Protexcoat™: UV Degradation Prevention MOVING HIGH PERFORMANCE FIBERS FORWARD POPULAR INDUSTRIAL FABRIC YARN PRODUCTS FIBER-LINE® Nominal Product ID Base Fiber Nominal -

Mary Walker Phillips: “Creative Knitting” and the Cranbrook Experience

Mary Walker Phillips: “Creative Knitting” and the Cranbrook Experience Jennifer L. Lindsay Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2010 ©2010 Jennifer Laurel Lindsay All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.............................................................................................iii PREFACE........................................................................................................................... x ACKNOWLDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... xiv INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 1. CRANBROOK: “[A] RESEARCH INSTITUTION OF CREATIVE ART”............................................................................................................ 11 Part 1. Founding the Cranbrook Academy of Art............................................................. 11 Section 1. Origins of the Academy....................................................................... 11 Section 2. A Curriculum for Modern Artists in Modern Times ........................... 16 Section 3. Cranbrook’s Landscape and Architecture: “A Total Work of Art”.... 20 Part 2. History of Weaving and Textiles at Cranbrook..................................................... 23 -

High Performance Fibers

High Performance Fibers One step ahead High Performance Fibers are engineered for extreme uses; whether the requirement is exceptional strength, stiffness, heat resistance and/or chemical resistance. EuroFibers is proud distribution partner of the leading brands in this industry with the ability to tailor these tough fibers to the need of our customers, whether it be coating, twisting, assembling, plying or cutting. HMPE Fiber Para-Aramid Fiber Ultra high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMwPE), high modulus Para-aramid fibers are a class of heat-resistant and extremely strong polyethylene (HMPE) or high performance polyethylene fibers (HPPE) synthetic fibers. The ultimate strength of some aramid fibers can are extremely strong and are the lightest of all ultra-strong fibers. exceed 3500 MPa. Aramid has an outstanding strength-to-weight The ultimate strength can exceed 3000 MPa. However, due to its low ratio, even better than carbon, and excellent dimensional stability melting point of about 150°C (295°F) they are not suitable for elevated due to the high young’s modulus. Para-aramid has a decomposition temperature applications. The fiber is mainly used in protective temperature of ± 500 ºC. Technora® is a para-aramid fiber made clothing like ballistic vests, helmets, cut-resistant glove and tension from copolymers and is produced in the different process from PPTA members like ropes, slings and fishing lines. (poly-paraphenylene terephthalamide). EuroFibers is the premium distributor of DSM offering the extensive EuroFibers is the premium distributor of Teijin® offering their Dyneema® and Trevo® portfolio to our customer base. exceptional aramid fibers Twaron® and Technora® to a wide variety of customers. -

19. Principles of Yarn Requirements for Knitting

19. Principles of Yarn Requirements for Knitting Errol Wood Learning objectives On completion of this lecture you should be able to: • Describe the general methods of forming textile fabrics; • Outline the fibre and yarn requirements for machine knitwear • Describe the steps in manufacturing and preparing yarn for knitting Key terms and concepts Weft knitting, warp knitting, fibres, fibre diameter, worsted system, yarn count, steaming, clearing, winding, lubrication, needle loop, sinker loop, courses, wales, latch needle, bearded needle Introduction Knitting as a method of converting yarn into fabric begins with the bending of the yarn into either weft or warp loops. These loops are then intermeshed with other loops of the same open or closed configuration in either a horizontal or vertical direction. These directions correspond respectively to the two basic forms of knitting technology – weft and warp knitting. In recent decades few sectors of the textile industry have grown as rapidly as the machine knitting industry. Advances in knitting technologies and fibres have led to a diverse range of products on the market, from high quality apparel to industrial textiles. The knitting industry can be divided into four groups – fully fashioned, flat knitting, circular knitting and warp knitting. Within the wool industry both fully fashioned and flat knitting are widely used. Circular knitting is limited to certain markets and warp knitting is seldom used for wool. This lecture covers the fibre and yarn requirements for knitting, and explains the formation of knitted structures. A number of texts are useful as general references for this lecture; (Wignall, 1964), (Gohl and Vilensky, 1985) and (Spencer, 1986). -

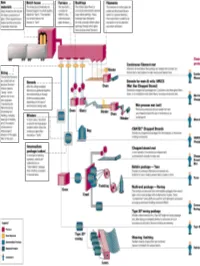

All About Fibers

RawRaw MaterialsMaterials ¾ More than half the mix is silica sand, the basic building block of any glass. ¾ Other ingredients are borates and trace amounts of specialty chemicals. Return © 2003, P. Joyce BatchBatch HouseHouse && FurnaceFurnace ¾ The materials are blended together in a bulk quantity, called the "batch." ¾ The blended mix is then fed into the furnace or "tank." ¾ The temperature is so high that the sand and other ingredients dissolve into molten glass. Return © 2003, P. Joyce BushingsBushings ¾The molten glass flows to numerous high heat-resistant platinum trays which have thousands of small, precisely drilled tubular openings, called "bushings." Return © 2003, P. Joyce FilamentsFilaments ¾This thin stream of molten glass is pulled and attenuated (drawn down) to a precise diameter, then quenched or cooled by air and water to fix this diameter and create a filament. Return © 2003, P. Joyce SizingSizing ¾The hair-like filaments are coated with an aqueous chemical mixture called a "sizing," which serves two main purposes: 1) protecting the filaments from each other during processing and handling, and 2) ensuring good adhesion of the glass fiber to the resin. Return © 2003, P. Joyce WindersWinders ¾ In most cases, the strand is wound onto high-speed winders which collect the continuous fiber glass into balls or "doffs.“ Single end roving ¾ Most of these packages are shipped directly to customers for such processes as pultrusion and filament winding. ¾ Doffs are heated in an oven to dry the chemical sizing. Return © 2003, P. Joyce IntermediateIntermediate PackagePackage ¾ In one type of winding operation, strands are collected into an "intermediate" package that is further processed in one of several ways. -

United States Patent 19 (11) 4,395,889 Schnegg 45) Aug

United States Patent 19 (11) 4,395,889 Schnegg 45) Aug. 2, 1983 54 WOVEN-LIKE WARP KNIT FABRC WITH TENSON CONTROL FOR TOP EFFECT OTHER PUBLICATIONS YARN Paling, “Warp Knitting Technology', 1952, London, p. 75 Inventor: Julius R. Schnegg, Burlington, N.C. 152. (73) Assignee: Burlington Industries, Inc., Primary Examiner-Ronald Feldbaum Greensboro, N.C. Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Cushman, Darby & Cushman 21 Appl. No.: 97,972 22 Filed: Nov. 28, 1979 57 ABSTRACT 51 Int. Cl’.............................................. D04B 23/08 An improved warp knit fabric that can serve as a base 52) U.S.C. ........................................ 66/193; 66/190; fabric for producing full weight, self-lined drapery ma 661202 terial as well as sheer drapery material and the process 58) Field of Search .................................. 66/190-195, and apparatus therefor. The base fabric is primarily 66/202 comprised of three groups of yarns knit together to 56 References Cited form a sheer fabric that creates the visual effect of being woven. The full weight is formed by incorporating one U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS or more additional groups of yarns into the base fabric. 3,036,448 5/1962 Cundiff............................... 66/195X One group is added to produce a self-lining on the rear 3,084,529 4/1963 Scheibe ... ... 66/193 side of the material while another group can include a 4,197,725 4f 1980 Kohl ...................................... 66,213 “laid-in' top effect yarn. This top effect yarn can be fed FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS with varying tension control so that a relatively wide 430022 8, 1967 Switzerland .......................... 66, 193 variety of effects can be created.