Supplementary Information Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Annual Report

Mattel Annual Report 2011 Click to play! Please visit: www.Mattel.com/AnnualReport The imagination of children inspires our innovation. Annual Report 2011 80706_MTL_AR11_Cover.indd 1 3/7/12 5:34 PM Each and every year, Mattel’s product line-up encompasses some of the most original and creative toy ideas in the world. These ideas have been winning the hearts of children, the trust of parents and the recognition of peers for more than 65 years. 80706_MTL_AR11_Text.indd 2 3/7/12 8:44 PPMM To Our Shareholders: am excited to be Mattel’s sixth environment. The year proved Chief Executive Offi cer in 67 to be a transition period for years, and honored to continue Fisher-Price with the expiration the legacy of such visionaries of the Sesame Street license as Mattel founders Ruth and and our strategic re-positioning Elliot Handler; Herman Fisher of the brand. and Irving Price, the name- sakes of Fisher-Price; Pleasant We managed our business Rowland, founder of American accordingly as these challenges Girl; and Reverend W. V. Awdry, played out during the year. We creator of Thomas & Friends®. maintained momentum in our core brands, such as Barbie®, First and foremost, I would like Hot Wheels®, American Girl® to acknowledge and thank and our new brand franchise, Bob Eckert for his tremendous Monster High®, as well as with contributions to the company key entertainment properties, during the last decade. Bob is such as Disney Princess® and a great business partner, friend CARS 2®. As a result, 2011 and mentor, and I am fortunate marks our third consecutive to still be working closely with year of solid performance: him as he remains Chairman revenues and operating of the Board. -

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Luka Doncic 1112 0 145 630 337 Joe Dumars 1101 0 460 441 200 Grant Hill 1030 0 560 220 250 Nikola Jokic 998 154 420 236 188 Elie Okobo 982 0 140 630 212 Karl-Anthony Towns 980 154 0 752 74 Marvin Bagley III 977 0 10 630 337 Kevin Knox 977 0 10 630 337 Deandre Ayton 977 0 10 630 337 Trae Young 977 0 10 630 337 Collin Sexton 967 0 0 630 337 Anthony Davis 892 154 112 626 0 Damian Lillard 885 154 186 471 74 Dominique Wilkins 856 0 230 550 76 Jaren Jackson Jr. 847 0 5 630 212 Toni Kukoc 847 0 420 235 192 Kyrie Irving 846 154 146 472 74 Jalen Brunson 842 0 0 630 212 Landry Shamet 842 0 0 630 212 Shai Gilgeous- 842 0 0 630 212 Alexander Mikal Bridges 842 0 0 630 212 Wendell Carter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Hamidou Diallo 842 0 0 630 212 Kevin Huerter 842 0 0 630 212 Omari Spellman 842 0 0 630 212 Donte DiVincenzo 842 0 0 630 212 Lonnie Walker IV 842 0 0 630 212 Josh Okogie 842 0 0 630 212 Mo Bamba 842 0 0 630 212 Chandler Hutchison 842 0 0 630 212 Jerome Robinson 842 0 0 630 212 Michael Porter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Troy Brown Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Joel Embiid 826 154 0 596 76 Grayson Allen 826 0 0 614 212 LaMarcus Aldridge 825 154 0 471 200 LeBron James 816 154 0 662 0 Andrew Wiggins 795 154 140 376 125 Giannis 789 154 90 472 73 Antetokounmpo Kevin Durant 784 154 122 478 30 Ben Simmons 781 154 0 627 0 Jason Kidd 776 0 370 330 76 Robert Parish 767 0 140 552 75 Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos -

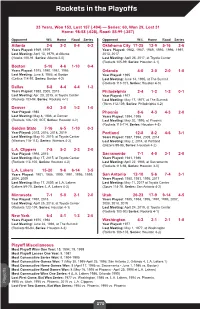

Rockets in the Playoffs

Rockets in the Playoffs 33 Years, Won 153, Lost 157 (.494) — Series: 60, Won 29, Lost 31 Home: 98-58 (.628), Road: 55-99 (.357) Opponent W-L Home Road Series Opponent W-L Home Road Series Atlanta 2-6 2-2 0-4 0-2 Oklahoma City 17-25 12-9 5-16 2-6 Years Played: 1969, 1979 Years Played: 1982, 1987, 1989, 1993, 1996, 1997, Last Meeting: April 13, 1979, at Atlanta 2013, 2017 (Hawks 100-91, Series: Atlanta 2-0) Last Meeting: April 25, 2017, at Toyota Center (Rockets 105-99, Series: Houston 4-1) Boston 5-16 4-6 1-10 0-4 Years Played: 1975, 1980, 1981, 1986 Orlando 4-0 2-0 2-0 1-0 Last Meeting: June 8, 1986, at Boston Year Played: 1995 (Celtics 114-97, Series: Boston 4-2) Last Meeting: June 14, 1995, at The Summit (Rockets 113-101, Series: Houston 4-0) Dallas 8-8 4-4 4-4 1-2 Years Played: 1988, 2005, 2015 Philadelphia 2-4 1-2 1-2 0-1 Last Meeting: Apr. 28, 2015, at Toyota Center Year Played: 1977 (Rockets 103-94, Series: Rockets 4-1) Last Meeting: May 17, 1977, at The Summit (76ers 112-109, Series: Philadelphia 4-2) Denver 4-2 3-0 1-2 1-0 Year Played: 1986 Phoenix 8-6 4-3 4-3 2-0 Last Meeting: May 8, 1986, at Denver Years Played: 1994, 1995 (Rockets 126-122, 2OT, Series: Houston 4-2) Last Meeting: May 20, 1995, at Phoenix (Rockets 115-114, Series: Houston 4-3) Golden State 7-16 6-5 1-10 0-3 Year Played: 2015, 2016, 2018, 2019 Portland 12-8 8-2 4-6 3-1 Last Meeting: May 10, 2019, at Toyota Center Years Played: 1987, 1994, 2009, 2014 (Warriors 118-113), Series: Warriors 4-2) Last Meeting: May 2, 2014, at Portland (Blazers 99-98, Series: Houston 4-2) L.A. -

Conducteur Chic

CCCHHHIIICCC ––– 444000 xxx 222666’’’ This image-packed feature program deciphers trends in fashion, architecture, gastronomy and design, presenting a world of creativity and wellbeing. Chic ! goes in search of those who aspire to a different way of life, and discovers surprising initiatives, off-beat life-styles, and unusual creations… “Chic ! meets” A creative talent welcomes us for four days to his or her world, interior, and town or city, sharing their favourite addresses, and revealing a personality of their choice: The designer Martino Gamper, pastry chef Cristian Escriba, interior designer Paola Navone, designer Zandra Rhodes… “Rising Trends” Deciphering new trends, discovering new practices: Temporary shops, cooking with candy, luxury for hire, the new bathrooms, fashion illustrators “A potted history” Exploring familiar every-day living though the history and etymology of cult objects, designer furniture, food, and inventions: Converse, table football, the fan, Monopoly, Chupa Chups, the Polaroïd… “Insights” Viewers invite us to visit an outstanding or unusual place and to discover their original or offbeat life styles: Puerta American Madrid, a restaurant in a church, living in a water tower, working under a tree… CCCOOONNNDDDUUUCCCTTTEEEUUURRR CCCHHHIIICCC Site web : http://www.arte.tv/fr/1905558.html PROGRAM N°1 “Chic ! meets” : Zandra Rhodes, Glam Rock fantasy Broadcast on 24 November 2005 We went to London to meet Zandra Rhodes. The designer, who was the height of fashion in the 60s, invites us to her London apartment on the roof of the Fashion and Textile Museum. A South American-style interior fuses with glam rock fantasy at her brightly coloured home. "A potted history" of the Mont Blanc pen Broadcast on 4 April 2006 This little gem of a writing implement was born in 1906 out of a meeting with three German businessmen. -

Barbie® Presents Unique Angela Merkel Barbie® Doll

Barbie® Presents Unique Angela Merkel Barbie® Doll The German chancellor honoured by Mattel at International Toy Fair in Nuremberg On Thursday 5th of February, Barbie will unveil a one of a kind Angela Merkel Barbie doll in honour and recognition of Germany's first female chancellor at the 60th International Toy Fair in Nuremberg, Germany. Barbie has chosen to honour and recognise the Chancellor Merkel as a very modern role model for girls. Chancellor Merkel has successfully led her country while also having major impact with her work in Europe, where she recently received the Charlemagne Prize in recognition of her relentless work to reform the European Union. "Angela Merkel is an incredible role model and with this unique Angela Merkel Barbie Doll we want to honour and recognize her impact and influence on women all over the world to whom she has been a tremendous inspiration." said Richard Dickson, GM and Senior Vice President of Barbie. "For 50 years Barbie has inspired girls to believe they can be anything, and Chancellor Merkel certainly brings that message to life for girls worldwide." With Forbes Magazine naming her "the most powerful woman in the world at present time" for three years in a row, Angela Merkel represents what lies at the core of the Barbie brand. As Ruth Handler, Barbie's creator, explained; "My whole philosophy of Barbie was that through the doll, the little girl could be anything she wanted to be. Barbie always represented the fact that a woman has choices." The Angela Merkel Barbie doll will be exhibited at the International Toy Fair in Mattel's showroom from the 5th-10th February, beginning a year of celebrations to mark Barbie's five decades as a Fashion Icon and Princess of Pop culture. -

Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of Us-C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 From "Ping-Pong Diplomacy" to "Hoop Diplomacy": Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of U.S.-China Relations Pu Haozhou Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION FROM “PING-PONG DIPLOMACY” TO “HOOP DIPLOMACY”: YAO MING, GLOBALIZATION, AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS By PU HAOZHOU A Thesis submitted to the Department of Sport Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Pu Haozhou defended this thesis on June 19, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Giardina Professor Directing Thesis Joshua Newman Committee Member Jeffrey James Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I’m deeply grateful to Dr. Michael Giardina, my thesis committee chair and advisor, for his advice, encouragement and insights throughout my work on the thesis. I particularly appreciate his endless inspiration on expanding my vision and understanding on the globalization of sports. Dr. Giardina is one of the most knowledgeable individuals I’ve ever seen and a passionate teacher, a prominent scholar and a true mentor. I also would like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Joshua Newman, for his incisive feedback and suggestions, and Dr. Jeffrey James, who brought me into our program and set the role model to me as a preeminent scholar. -

H Oya B Asketball G Eorgetow N Staff Team R Eview Tradition R Ecords O Pponents G U Athletics M Edia

9 2 2006-07 GEORGETOWN MEN’S BASKETBALL HoyaHoya BasketballBasketball GGeorgetowneorgetown StaffStaff TeamTeam ReviewReview Tradition Records Opponents GU Athletics Media Tradition Staff Staff Georgetown Basketball Hoya Team Team Review Tradition Media Athletics GU Opponents Records 2006-072 0 0 6 - 0 7 GEORGETOWNG E O R G E T O W N MEN’SM E N ’ S BASKETBALLB A S K E T B A L L 9 3 Basketball Hoya Georgetown Staff Hoya Tradition In its fi rst 100 years, the Georgetown Basketball program has been highlighted by rich tradition... Historical records show us the accomplishments of future Congressman Henry Hyde and his team in the 1940s. Professional achievement tells us of the academic rigor and athletic pursuits of the 1960s that helped shape Paul Tagliabue, former Commissioner of the NFL. Trophies, awards and championships are evidence of the success John Thompson Jr. compiled in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. It is the total combination: academic and athletic excellence, focus, dedication and hard work instilled in Hoya teams throughout the last century that built men who would not only conquer the basketball court, but serve their communities. This is the tradition of Georgetown University and its basketball program. Team Team Review Review Tradition 1942 Buddy O’Grady, Al Lujack and Don Records Opponents Athletics GU Media 1907 1919 Bill Martin graduate and are selected by the Bornheimer Georgetown beats Virginia, 22-11, in the Led by Fred Fees and Andrew Zazzali, National Basketball Association. They are fi rst intercollegiate basketball game in the Hilltop basketball team compiles the fi rst of 51 Hoyas to play in the NBA. -

Roveri Fernandatheodoro M.Pdf

© by Fernanda Theodoro Roveri, 2008. Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca da Faculdade de Educação/UNICAMP Roveri, Fernanda Theodoro. R769b Barbie : tudo o que você quer ser... : ou considerações sobre a educação de meninas / Fernanda Theodoro Roveri. -- Campinas, SP: [s.n.], 2008. Orientadora : Carmen Lúcia Soares. Dissertação (mestrado) œ Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Faculdade de Educação. 1. Corpo. 2. Brinquedo. 3. Infância. 4. Gênero. 5. Educação. I. Soares, Carmen Lúcia. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Faculdade de Educação. III. Título. 08-113/BFE Título em inglês : Barbie : everything you want to be... : or considerations about girl‘s education Keywords: Barbie; Body; Toy; Childhood; Gender; Education Êrea de concentração: Educação, Conhecimento, Linguagem e Arte Titulação: Mestre em Educação Banca examinadora: Profª. Drª. Carmen Lúcia Soares (Orientadora) Profª. Drª. Roseli Aparecida Cação Fontana Profª. Drª. Helena Altmann Profª. Drª. Kátia Danailof Profª. Drª. Eliana Ayoub Data da defesa: 13/08/2008 Programa de pós-graduação : Educação e-mail : [email protected] Aos meus pais, Sergio e Eleusa, pela vida e pelos ensinamentos... a semente, a casca, o sumo À minha irmã Michelle, com quem vivi a imaginação da infância... o sumo espremido, o mosto À querida professora Carmen Soares, pelo acolhimento nos desafios vividos no transcorrer da pesquisa... a madeira, o tempo, a textura aveludada . Ao meu marido Rodrigo, pela intensa colaboração no cultivo deste trabalho que agora degustamos juntos... o bouquet e as lágrimas. iii Agradecimentos À Mariana Guimarães, querida amiga, que com disposição me ajudou nas leituras em inglês. Aos amigos “efhistória” : André, Evelise, Felipe, Kátia, Leonardo, Rodrigo, Rogério, Sandra e Sílvia, pelo companheirismo e valiosas sugestões. -

A Closer Look at How One Asian Is a Representative for an Entire Race

Linplexity: A Closer Look at How One Asian is a Representative for an Entire Race Ryan Kitaro Kwai-ming Hata, San Francisco State University, USA The Asian Conference on Media & Mass Communication 2014 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract Asians specifically in America, negotiate with the depictions of microaggressions rooted in racism in everyday life. According to Derald W. Sue et al. (2007), “racial microaggressions are brief and commonplace daily, verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communication hostile, derogatory; or negative racial slights and insults towards people of color” (p. 271). Common microaggressions imposed on Asian Americans in the media are their portrayal as perpetual foreigners, “Yellow Perils,” or the model minority. The image of Jeremy Lin as the “model minority,” low-keyed, passive athlete is seldom problematized and often encouraged by mainstream media. However, Asian scholars, sports commentators, filmmakers and journalists have noticed mainstream media unconsciously or uncritically directs microaggressions at Jeremy Lin through the model minority myth. Hence, the tension in these portrayals of Asians through Lin on an individual level as the model minority constitutes and extends the microaggression. Using Critical Race Theory and “symbolic microaggressions,” my research will apply content and critical discourse analysis to provide a clearer picture of Lin to deconstruct Asian stereotypes, microaggressions, and colorblindness. I will be comparing and contrasting non-Asian media perceptions of Jeremy Lin with the Linsanity documentary (directed and produced by Asian Americans). Can Jeremy Lin’s portrayal in mainstream media as a model minority be oppressive and empowering at the same time? Finally, I will seek to address the larger impact of this work on Jeremy Lin in terms of how the media represents Asians both in United States and globally. -

« Am I Black Enough for You? » Basket-Ball, Médias Et Culture Afro-Américaine Aux États-Unis (1950-2015)

UNIVERSITÉ SORBONNE NOUVELLE – PARIS 3 ED 514 – EDEAGE ÉTUDES ANGLOPHONES, GERMANOPHONES ET EUROPÉENNES EA 4399 – CREW CENTER FOR RESEARCH ON THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING WORLD Thèse de doctorat Anglais (civilisation américaine) Yann DESCAMPS « Am I Black Enough for You? » Basket-ball, médias et culture afro-américaine aux États-Unis (1950-2015) VOLUME 2 : Annexes Thèse dirigée par Mme la Professeure Divina FRAU-MEIGS Soutenue publiquement le 4 décembre 2015 Jury : - M. Daniel DURBIN, Professeur, University of Southern California - Mme Divina FRAU-MEIGS, Professeur, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3 - M. Jean-Paul GABILLIET, Université Bordeaux Montaigne - M. Olivier PÉGARD, Maître de Conférence, Université Paris-Est Créteil Val-de-Marne - M. Georges VIGARELLO, Professeur émérite, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales 2 Annexe n°1 : Entretiens Entretien avec Tariq Abdul-Wahad Ancien joueur universitaire (Michigan State) et NBA (Sacramento, Orlando, Denver, Dallas). Entraîneur d’une équipe de lycée à San José. Propos recueillis le 24 février 2014 en marge d’une conférence à USC. « It was like you had black kids from New York in the 1960s being coached by white men from Mississippi. The cultural disconnect was that drastic. France, because of its colonies, half the team is black. There was a serious disconnect between the players and the staff. When I was a rookie, we had 3 meetings: one to manage your money, one for security matters, one to handle lovers. All this was meant to protect the NBA brand, the corporate brand. We’re athletes, but we’re more than athletes. I would love to see these corporations consider athletes as individuals, just as they consider themselves. -

Barbie As Cultural Compass

College of the Holy Cross CrossWorks Sociology Student Scholarship Sociology & Anthropology Department 5-2017 Barbie As Cultural Compass: Embodiment, Representation, and Resistance Surrounding the World’s Most Iconized Doll Hannah Tulinski College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://crossworks.holycross.edu/soc_student_scholarship Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Tulinski, Hannah, "Barbie As Cultural Compass: Embodiment, Representation, and Resistance Surrounding the World’s Most Iconized Doll" (2017). Sociology Student Scholarship. 1. http://crossworks.holycross.edu/soc_student_scholarship/1 This Department Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology & Anthropology Department at CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of CrossWorks. “Barbie As Cultural Compass: Embodiment, Representation, and Resistance Surrounding the World’s Most Iconized Doll” Hannah Rose Tulinski Department of Sociology & Anthropology College of the Holy Cross May 2017 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Chapter 1: Barbie™ 5 Chapter 2: Cultural Objects and the Meaning of Representation 30 Chapter 3: Locating Culture in Discourse 45 Chapter 4: Barbie’s World is Our World 51 Chapter 5: Competing Directions of Cultural Production 74 Chapter 6: Role Threat 89 Role Transformation 104 Discussion 113 References 116 Appendix I: Popular Discourse 122 Appendix II: Scholarly Discourse 129 2 Acknowledgements First, thank you to Professor Selina Gallo-Cruz, who not only advised this thesis project but also who has mentored me throughout my development at College of the Holy Cross. -

Chen Gao | [email protected] Sport and Recreation Studies | George Mason University

Alley-opp between NBA and CBA:learning successful marketing strategies to improve the development of CBA. Chen Gao | [email protected] Sport and Recreation Studies | George Mason University Introduction Components of NBA’s expanding in China National Basketball Association (NBA) is the largest professional basketball After landing in Chinese basketball market, NBA took many effective measures to expand tournament in the United States, represents the highest level of basketball in the its popularity in China. Sun et al (2010) illustrated that the establishment of NBA China is world, which produced Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson, Kobe Bryant, Yao one of the most significant symbol of NBA’s expanding in China, which is important to both Ming, Lebron James, and other superstars in the world. Chinese Basketball NBA and CBA. They also found that NBA is attracting millions of fans in China, especially Association (CBA) is China's local league, representing the Chinese basketball. young professional basketball fans, which shows that NBA is expanding its popularity in Since David Stern took over the commissioner’s chair in 1980s, NBA has Chinese basketball fans. Actually, the role of NBA China in basketball fans, especially young implemented global strategies in order to expand its popularity around the basketball fans in China is like a base camp. When they want to get the lastest information, world. As the most populous country in the world, China has the biggest such as a NBA superstar’s schedule in China, NBA China is the first choice for them to get basketball market, which has a great attraction to NBA.