Report and the Committee Proceedings Are Available Online At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.1 Passamaquoddy, They Speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (Also Known As Maliseet- Passamaquoddy

1.1 Passamaquoddy, they speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (also known as Maliseet- Passamaquoddy. It is an endangered language from the Algonquian language family (1) 1.2 Pqm (2) 1.3 45.3,-66.656 (3) 1.4 The Passamaquoddy tribe belonged to the loose confederation of eastern American Indians known as the Wabanaki Alliance, together with the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Abenaki, and Penobscot tribes. Today most Passamaquoddy people live in Maine, in two communities along the Passamaquoddy Bay that bears their name. However, there is also a band of a few hundred Passamaquoddy people in New Brunswick. The French referred to both the Passamaquoddy and their Maliseet kinfolk by the same name, "Etchimins." They were closely related peoples who shared a common language, but the two tribes have always considered themselves politically independent. Smallpox and other European diseases took a heavy toll on the Passamaquoddy tribe, which was reduced from at least 20,000 people to no more than 4000. Pressured by European and Iroquois aggression, the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy banded together with their neighbors the Abenakis, Penobscots, and Micmacs into the short-lived but formidable Wabanaki Confederacy. This confederacy was no more than a loose alliance, however, and neither the Maliseet nor the Passamaquoddy nation ever gave up their sovereignty. Today the Passamaquoddy live primarily in the United States and the Maliseet in Canada, but the distinction between the two is not imposed by those governments--the two tribes have always been politically distinct entities. (4) 1.5 After working with the French and joining the Abnaki confederation against the English, many converted to Catholicism. -

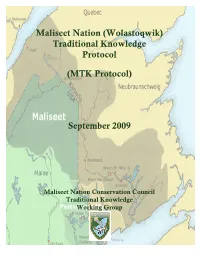

Traditional Knowledge Protocol

Maliseet Nation (Wolastoqwik) Traditional Knowledge Protocol (MTK Protocol) September 2009 Maliseet Nation Conservation Council Traditional Knowledge Working Group Table of Contents Foreword …………………………………………………………………………… i 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 1 2.0 Definitions …………………………………………………………………… 2 3.0 Interpretation ………………………………………………………………… 3 4.0 MTK Methodology …………………………………………………………… 4 I Project Planning ………………………………………………………… 5 II Delivery and Implementation ……………………………………………… 6 III Finalizing Report and Disclosure ………………………………………… 7 5.0 Amendments …………………………………………………………………… 7 Appendices …………………………………………………………………………… 8 Maliseet Leadership Proclamation / Resolution …………………………… 9 Draft Maliseet Ethics Guidelines ……………………………………… 10 Foreword Development of the Maliseet Nation Traditional Knowledge (MTK) Protocol highlights the recognition of the importance of Aboriginal traditional knowledge in relation to the environmental issues facing Maliseet traditional territory, the Saint John River (Wolustok) watershed1. The protection of such knowledge has been identified by the Maliseet Chiefs as a crucial component for future relations with non-Aboriginals, as increasing development activity continues to cause concern for all parties on the best way to proceed, in the spirit of cooperation and with due respect for Maliseet Aboriginal and Treaty rights2. The protocol also addresses past problems with research projects such as lack of consultation of Maliseet people, lack of meaningful community involvement, lack of benefit from research, lack of informed consent, lack of community ownership of data (including analysis, interpretation, recording or access), and lack of respect of our culture and beliefs by outside researchers. Initiated by the Maliseet Nation Conservation Council and produced through the combined efforts of informed Maliseet Elders, leaders, committees and grassroots volunteers, this protocol identifies the methods developed by the Maliseet Nation for the proper and thorough collection and use of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). -

Regular Meeting of the Council of the District of North Saanich Monday, October 20, 2014 at 7:00 P.M

Regular Meeting of the Council of the District of North Saanich Monday, October 20, 2014 at 7:00 p.m. (Please note that all proceedings are recorded) AGENDA PAGE NO. 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. PUBLIC HEARINGS 3. INTRODUCTION OF LATE ITEMS 4. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 5. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION PERIOD Rules of Procedure: 1) Persons wishing to address Council must state their name and address for identification and also the topic involved. 2) Subjects must be on topics which are not normally dealt with by municipal staff as a matter of routine. 3) Subjects must be brief and to the point. 4) Subjects shall be address through the Chair and answers given likewise. Debates with or by individual Council members will not be allowed. 5) No commitments shall be made by the Chair in replying to a question. Matters which may require action of the Council shall be referred to a future meeting of the Council. 6) Twenty minutes will be allotted for the Public Participation Period. 7) Each speaker under this section is limited to speaking for 3 minutes unless authorized by the Chair to speak for a longer period of time. 8) All questions from member of the public must be directed to the Chair. Members of the public are not permitted to direct their questions or comments to members of Staff. 9) Persons speaking during Public Participation period must: (a) use respectful language; (b) not use offensive gestures or signs; and (c) adhere to the rules of procedure established under this Bylaw and to the decisions of the Chair and Council in connection with the rules and points of order. -

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations February 2017 Nicole Friederichs Amy Van Zyl-Chavarro Kate Bertino Commissioned by the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission Contact Information: 120 Tremont Street Nicole Friederichs Boston, MA 02108 Practitioner-in-Residence Tel.: 1-617-305-1682 Indigenous Peoples Rights Clinic Fax: 1-617-573-8100 Suffolk University Law School Email: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission (MITSC) is honored to offer this thorough review of the crafting of the Federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, 25 U.S.C. §§ 1721-1735. In June of 2014, the MITSC completed the Assessment of the Intergovernmental Saltwater Fisheries Conflict between Passamaquoddy and the State of Maine where the MITSC offered the following framework: The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, (MICSA), was passed in October of the same year [1980]. The MICSA gave federal permission for the [state Maine Implementing Act] (MIA) to take effect while retaining intact the federal trust relationship between the federally recognized tribes of Maine and the US Congress; and placed constraints on the implementation of the MIA. Of particular interest to the inquiry into the saltwater fishery conflict between the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the State of Maine are the following provisions of the federal act: 1. MICSA (25 U.S.C. § 1735 (a)) provides that “In the event a conflict of interpretation between the provisions of the Maine Implementing Act and this Act should emerge, the provisions of this Act shall govern.” The provisions of the federal MICSA thus override the MIA provisions when there is a conflict between the two. -

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story Written by Cindy Blackstock Illustrated by Amanda Strong Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N) zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee- chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc -

AVAILABLE from Jamaica Plains, MA 02130

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 226 893 RC 013 868 AUTHOR Braber, Lee; Dean, Jacquelyn M. TITLE A Teacher Training Manual on NativeAmericans: The Wabanakis. INSTITUTION Boston Indian Council, Inc., JamaicaPlain, MA. SPONS AGENCY Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (ED), Washington, D.C. Ethnic Heritage Studies Program. PUB DATE 82 NOTE 74p.; For related document, see RC 013 869. AVAILABLE FROMBoston Indian Council, 105 South Huntington Ave., Jamaica Plains, MA 02130 ($8.00 includes postage and handling, $105.25 for 25 copies). PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indian Education; *Cultural Awareness; Elementary Secondary Education; *Enrichment Activities; Legends; *Life Style; Resource Materials; Teacher Qualifications;Tribes; *Urban American Indians IDENTIFIERS American Indian History; Boston Indian Council MA; Maliseet (Tribe); Micmac (Tribe); Passamaquoddy (Tribe); Penobscot (Tribe); Seasons; *Teacher Awareness; *Wabanaki Confederacy ABSTRACT The illustrated boóklet, developed by theWabanaki Ethnic Heritage Curriculum Development Project,is written for the Indian and non-Indian educator as a basic primer onthe Wabanaki tribal lifestyle. The Wabanaki Confederacy is made upof the following tribes: Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy,and Penobscot. Advocating a positive approach to teaching aboutNative Americans in general and highlighting the Wabanaki wayof life, past and present, the booklet is divided into four parts: anintroduction, Native American awareness, the Wabanakis, and appendices.Within these four parts, the teacher is given a brief look atNative American education, traditional legends, the lifestyleof the Wabanaki, the Confederacy, seasonal activities, and thechanges that occured when the Europeans came. An awareness of theWabanakis in Boston and the role of the Boston Indian Council, Inc., areemphasized. -

Aboriginal Place Names Rimouski: (Quebec) This Is a Word of Mi’Kmaq Or Contribute to a Rich Tapestry

Pamphlet # 24 Ontario: This Huron name, first applied to the lake, the Chipewyan people, and means "pointed skins," a may be a corruption of onitariio, meaning "beautiful Cree reference to the way the Chipewyan prepared lake," or kanadario, which translates as "sparkling" or beaver pelts. Aboriginal Peoples Contributions to "beautiful" water. Place Names in Canada Medicine Hat: (Alberta) This is a translation of the Quebec: Aboriginal peoples first used the name Blackfoot word, saamis, meaning "headdress of a 1 Provinces and Territories "kebek" for the region around Québec City. It refers medicine man." According to one explanation, the to the Algonquin word for "narrow passage" or word describes a fight between the Cree and The map of Canada is a rich tapestry of place names "strait" to indicate the narrowing of the river at Cape Blackfoot, when a Cree medicine man lost his which reflect the diverse history and heritage of our Diamond. plumed hat in the river. nation. Many of the country's earliest place names draw on Aboriginal sources. Before the arrival of Yukon: This name belonged originally to the Yukon Wetaskiwin: (Alberta) This is an adaptation of the Europeans, First Nations and Inuit peoples gave river and is from a Loucheux (Dene) word, LoYu- Cree word wi-ta-ski-oo cha-ka-tin-ow, which can be names to places throughout the country to identify kun-ah, meaning "great river." translated as "place of peace" or "hill of peace." the land they knew so well and with which they had strong spiritual connections. For centuries, these Nunavut: This is the name of Canada's newest Saskatoon: (Saskatchewan) The name comes from names that described the natural features of the land, territory which came into being on April 1, 1999. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Métis Identity in Canada

Métis Identity in Canada by Peter Larivière A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Geography Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2015, Peter Larivière Abstract The understanding and acknowledgement of Aboriginal rights has grown in importance within Canada as a result of the ever changing legal landscape and as Aboriginal groups more forcefully confront decades of colonial rule to assert their historic rights. While this has predominantly come out of First Nations issues, there has been a gradual increase in the rights cases by Métis communities. Primary among these was the 2003 Supreme Court of Canada Powley decision which introduced how Métis identity and community identification are key in a successful litigation claim by Métis. This research considers questions surrounding the contentious nature of Métis identity including how Métis see themselves and how their understandings are prescribed by others including the state, through tools such as the Census of Canada. ii Acknowledgements There is always a fear in acknowledging the support of individuals who assisted over the years that someone may be missed. So let me thank all those whose paths I have crossed and who in their own way set the stage for my being in this very place at this time. Without you I would not have made it here and I thank you. There are specific people who I do wish to highlight. My mother and father and my sister and her family all played a role not only in my formative years but continue to be part of my every day. -

J. Wayne Rowe, Mayor of Gibsons, BC. 474 S. Fletcher Rd., Gibsons, BC, VON WO UNITED CANADIAN Aftris NATION [Formerly Vancouver

ere) UNITED CANADIAN Aftris NATION [Formerly Vancouver Metis Citizens Society] 5619 Curtis Place, Sechelt, BC, VON 3A7, Phone: (604) 741-3813 Email: metisron(aigmail.com October 24, 2017 J. Wayne Rowe, Mayor of Gibsons, BC. 474 S. Fletcher Rd., Gibsons, BC, VON WO Dear Mayor Rowe: Re: Metis Recognition on November 16' "Louis Riel Day" On behalf of the United Canadian Metis Nation (UCMN) [formerly Vancouver Mans Citizens Society] and its many members living on the Sunshine Coast, we wish to request that the Town of Gibsons again recognize the Metis and their contributions to the early development of British Columbia and Canada. The President and several of its directors are residents of the Sunshine Coast. Our purpose is twofold: 1. To again bring to your attention a landmark day in Metis history — November 16th — a commemorative day that is celebrated by Metis people in British Columbia and across Canada. This occasion was formally recognized by Gibsons in 2014, 2015, and 2016 by the issuance of a Metis Cultural Awareness Week Proclamation, and by the flying of the Metis Infinity Flag in 2016. 2. To request that you again this year formally recognize the significance of November 16, 2017 to the Metis of your community by: (a) The issuance of a Proclamation declaring Louis Riel Day or Metis Cultural Awareness Week. The Proclamation would be similar to those issued in the past by Gibsons, the Province of British Columbia and cities such as Victoria, Surrey, Nanaimo, Penticton, and many others. (b) Publicly flying the Metis Infinity Flag as was done in 2015 and 2016 on the grounds of the British Columbia Parliament Buildings. -

“Just Do It!” Self-Determination for Complex Minorities

“Just Do It!” Self-Determination for Complex Minorities By Janique F. Dubois A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Janique F. Dubois, 2013 “Just Do It!” Self-Determination for Complex Minorities Janique F. Dubois Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This thesis explores how Indigenous and linguistic communities achieve self- determination without fixed cultural and territorial boundaries. An examination of the governance practices of Métis, Francophones and First Nations in Saskatchewan reveals that these communities use innovative membership and participation rules in lieu of territorial and cultural criteria to delineate the boundaries within which to exercise political power. These practices have allowed territorially dispersed communities to build institutions, adopt laws and deliver services through province-wide governance structures. In addition to providing an empirical basis to support non-territorial models of self-determination, this study offers a new approach to governance that challenges state- centric theories of minority rights by focusing on the transformative power communities generate through stories and actions. ii Acknowledgements I would not have been able to complete this project without the generosity and kindness of family, friends, mentors and strangers. I am indebted to all of those who welcomed me in their office, invited me into their homes and sat across from me in restaurants to answer my questions. For trusting me with your stories and for the generosity of your time, thank you, marci, merci, hay hay. I am enormously grateful to my committee members for whom I have the utmost respect as scholars and as people. -

The Sioux- Métis Wars

FALL 2007 ÉTIS OYAGEUR M THE PUBLICATION OFV THE MÉTIS NATION OF ONTARIO SINCE 1997 THE SIOUX- MÉTIS WARS NEW BOOK EXPLORES THIS LITTLE KNOWN CHAPTER OF MÉTIS HISTORY PAGE 27 SPECIAL SECTION AGA AT THE MÉTIS RENDEZVOUS 2007 Camden Connor McColl makes quite the Métis Voyageur atop his IT’S BACK TO THUNDER grandfather Vic Brunelle’s shoulders BAY FOR ANOTHER as the Georgian Bay Métis commu- GREAT MÉTIS NATION nity hosts the third annual Métis OF ONTARIO ASSEMBLY Rendezvous at the Lafontaine Parks PAGES 11- 22 and Recreation Centre, on Saturday September 29th, 2007. Check out BRENDA our next issue for more on this year’s POWLEY Rendezvous. INTERVIEW WITH A PROUD FIGHTER FOR MÉTIS RIGHTS. PAGE 9 MÉTIS FAMILIES LEARNING TOGETHER MNO INTRODUCES NEW LITERACY PROGRAM. PAGE 3 1785370 PHOTO: Scott Carpenter 2 MÉTIS VOYAGEUR Captain’s WEDDING BELLS OBITUARY Corner BY KEN SIMARD CAPTAIN OF THE HUNT, REG. 2 ATTENTION MÉTIS HUNTERS! Sahayma Many Métis Citizen harvesters Parker and Isaac Omenye are still have not reported their Marie-Claire Dorion-Dumont proud to announce the arrival of 29 November 1938 - 18 August 2007 harvest for the year 2006. their baby sister, Sahayma Orillia ——————— PLEASE DO SO NOW! This is Sarah, born on July 13, 2007, It is with deep sadness that the very important for our weighing 8 lbs. 1 oz. Proud par- We are happy to join Judi Trott in announcing the marriage of Melissa Dumont family announces the pass- records. Our negotiating ents are Kelly and George Cabezas to Mr Jason Button on March 9th, 2007.