L3: a Linear Language with Locations 1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

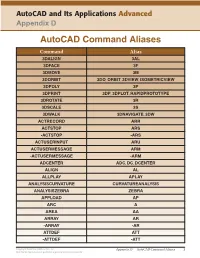

Autocad Command Aliases

AutoCAD and Its Applications Advanced Appendix D AutoCAD Command Aliases Command Alias 3DALIGN 3AL 3DFACE 3F 3DMOVE 3M 3DORBIT 3DO, ORBIT, 3DVIEW, ISOMETRICVIEW 3DPOLY 3P 3DPRINT 3DP, 3DPLOT, RAPIDPROTOTYPE 3DROTATE 3R 3DSCALE 3S 3DWALK 3DNAVIGATE, 3DW ACTRECORD ARR ACTSTOP ARS -ACTSTOP -ARS ACTUSERINPUT ARU ACTUSERMESSAGE ARM -ACTUSERMESSAGE -ARM ADCENTER ADC, DC, DCENTER ALIGN AL ALLPLAY APLAY ANALYSISCURVATURE CURVATUREANALYSIS ANALYSISZEBRA ZEBRA APPLOAD AP ARC A AREA AA ARRAY AR -ARRAY -AR ATTDEF ATT -ATTDEF -ATT Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. Appendix D — AutoCAD Command Aliases 1 May not be reproduced or posted to a publicly accessible website. Command Alias ATTEDIT ATE -ATTEDIT -ATE, ATTE ATTIPEDIT ATI BACTION AC BCLOSE BC BCPARAMETER CPARAM BEDIT BE BLOCK B -BLOCK -B BOUNDARY BO -BOUNDARY -BO BPARAMETER PARAM BREAK BR BSAVE BS BVSTATE BVS CAMERA CAM CHAMFER CHA CHANGE -CH CHECKSTANDARDS CHK CIRCLE C COLOR COL, COLOUR COMMANDLINE CLI CONSTRAINTBAR CBAR CONSTRAINTSETTINGS CSETTINGS COPY CO, CP CTABLESTYLE CT CVADD INSERTCONTROLPOINT CVHIDE POINTOFF CVREBUILD REBUILD CVREMOVE REMOVECONTROLPOINT CVSHOW POINTON Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. Appendix D — AutoCAD Command Aliases 2 May not be reproduced or posted to a publicly accessible website. Command Alias CYLINDER CYL DATAEXTRACTION DX DATALINK DL DATALINKUPDATE DLU DBCONNECT DBC, DATABASE, DATASOURCE DDGRIPS GR DELCONSTRAINT DELCON DIMALIGNED DAL, DIMALI DIMANGULAR DAN, DIMANG DIMARC DAR DIMBASELINE DBA, DIMBASE DIMCENTER DCE DIMCONSTRAINT DCON DIMCONTINUE DCO, DIMCONT DIMDIAMETER DDI, DIMDIA DIMDISASSOCIATE DDA DIMEDIT DED, DIMED DIMJOGGED DJO, JOG DIMJOGLINE DJL DIMLINEAR DIMLIN, DLI DIMORDINATE DOR, DIMORD DIMOVERRIDE DOV, DIMOVER DIMRADIUS DIMRAD, DRA DIMREASSOCIATE DRE DIMSTYLE D, DIMSTY, DST DIMTEDIT DIMTED DIST DI, LENGTH DIVIDE DIV DONUT DO DRAWINGRECOVERY DRM DRAWORDER DR Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. -

CS101 Lecture 9

How do you copy/move/rename/remove files? How do you create a directory ? What is redirection and piping? Readings: See CCSO’s Unix pages and 9-2 cp option file1 file2 First Version cp file1 file2 file3 … dirname Second Version This is one version of the cp command. file2 is created and the contents of file1 are copied into file2. If file2 already exits, it This version copies the files file1, file2, file3,… into the directory will be replaced with a new one. dirname. where option is -i Protects you from overwriting an existing file by asking you for a yes or no before it copies a file with an existing name. -r Can be used to copy directories and all their contents into a new directory 9-3 9-4 cs101 jsmith cs101 jsmith pwd data data mp1 pwd mp1 {FILES: mp1_data.m, mp1.m } {FILES: mp1_data.m, mp1.m } Copy the file named mp1_data.m from the cs101/data Copy the file named mp1_data.m from the cs101/data directory into the pwd. directory into the mp1 directory. > cp ~cs101/data/mp1_data.m . > cp ~cs101/data/mp1_data.m mp1 The (.) dot means “here”, that is, your pwd. 9-5 The (.) dot means “here”, that is, your pwd. 9-6 Example: To create a new directory named “temp” and to copy mv option file1 file2 First Version the contents of an existing directory named mp1 into temp, This is one version of the mv command. file1 is renamed file2. where option is -i Protects you from overwriting an existing file by asking you > cp -r mp1 temp for a yes or no before it copies a file with an existing name. -

Shell Variables

Shell Using the command line Orna Agmon ladypine at vipe.technion.ac.il Haifux Shell – p. 1/55 TOC Various shells Customizing the shell getting help and information Combining simple and useful commands output redirection lists of commands job control environment variables Remote shell textual editors textual clients references Shell – p. 2/55 What is the shell? The shell is the wrapper around the system: a communication means between the user and the system The shell is the manner in which the user can interact with the system through the terminal. The shell is also a script interpreter. The simplest script is a bunch of shell commands. Shell scripts are used in order to boot the system. The user can also write and execute shell scripts. Shell – p. 3/55 Shell - which shell? There are several kinds of shells. For example, bash (Bourne Again Shell), csh, tcsh, zsh, ksh (Korn Shell). The most important shell is bash, since it is available on almost every free Unix system. The Linux system scripts use bash. The default shell for the user is set in the /etc/passwd file. Here is a line out of this file for example: dana:x:500:500:Dana,,,:/home/dana:/bin/bash This line means that user dana uses bash (located on the system at /bin/bash) as her default shell. Shell – p. 4/55 Starting to work in another shell If Dana wishes to temporarily use another shell, she can simply call this shell from the command line: [dana@granada ˜]$ bash dana@granada:˜$ #In bash now dana@granada:˜$ exit [dana@granada ˜]$ bash dana@granada:˜$ #In bash now, going to hit ctrl D dana@granada:˜$ exit [dana@granada ˜]$ #In original shell now Shell – p. -

Linux Cheat Sheet

1 of 4 ########################################### # 1.1. File Commands. # Name: Bash CheatSheet # # # # A little overlook of the Bash basics # ls # lists your files # # ls -l # lists your files in 'long format' # Usage: A Helpful Guide # ls -a # lists all files, including hidden files # # ln -s <filename> <link> # creates symbolic link to file # Author: J. Le Coupanec # touch <filename> # creates or updates your file # Date: 2014/11/04 # cat > <filename> # places standard input into file # Edited: 2015/8/18 – Michael Stobb # more <filename> # shows the first part of a file (q to quit) ########################################### head <filename> # outputs the first 10 lines of file tail <filename> # outputs the last 10 lines of file (-f too) # 0. Shortcuts. emacs <filename> # lets you create and edit a file mv <filename1> <filename2> # moves a file cp <filename1> <filename2> # copies a file CTRL+A # move to beginning of line rm <filename> # removes a file CTRL+B # moves backward one character diff <filename1> <filename2> # compares files, and shows where differ CTRL+C # halts the current command wc <filename> # tells you how many lines, words there are CTRL+D # deletes one character backward or logs out of current session chmod -options <filename> # lets you change the permissions on files CTRL+E # moves to end of line gzip <filename> # compresses files CTRL+F # moves forward one character gunzip <filename> # uncompresses files compressed by gzip CTRL+G # aborts the current editing command and ring the terminal bell gzcat <filename> # -

Configuring Your Login Session

SSCC Pub.# 7-9 Last revised: 5/18/99 Configuring Your Login Session When you log into UNIX, you are running a program called a shell. The shell is the program that provides you with the prompt and that submits to the computer commands that you type on the command line. This shell is highly configurable. It has already been partially configured for you, but it is possible to change the way that the shell runs. Many shells run under UNIX. The shell that SSCC users use by default is called the tcsh, pronounced "Tee-Cee-shell", or more simply, the C shell. The C shell can be configured using three files called .login, .cshrc, and .logout, which reside in your home directory. Also, many other programs can be configured using the C shell's configuration files. Below are sample configuration files for the C shell and explanations of the commands contained within these files. As you find commands that you would like to include in your configuration files, use an editor (such as EMACS or nuTPU) to add the lines to your own configuration files. Since the first character of configuration files is a dot ("."), the files are called "dot files". They are also called "hidden files" because you cannot see them when you type the ls command. They can only be listed when using the -a option with the ls command. Other commands may have their own setup files. These files almost always begin with a dot and often end with the letters "rc", which stands for "run commands". -

Configuration and Administration of Networking for Fedora 23

Fedora 23 Networking Guide Configuration and Administration of Networking for Fedora 23 Stephen Wadeley Networking Guide Draft Fedora 23 Networking Guide Configuration and Administration of Networking for Fedora 23 Edition 1.0 Author Stephen Wadeley [email protected] Copyright © 2015 Red Hat, Inc. and others. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https://fedoraproject.org/wiki/ Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. -

System Analysis and Tuning Guide System Analysis and Tuning Guide SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 15 SP1

SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 15 SP1 System Analysis and Tuning Guide System Analysis and Tuning Guide SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 15 SP1 An administrator's guide for problem detection, resolution and optimization. Find how to inspect and optimize your system by means of monitoring tools and how to eciently manage resources. Also contains an overview of common problems and solutions and of additional help and documentation resources. Publication Date: September 24, 2021 SUSE LLC 1800 South Novell Place Provo, UT 84606 USA https://documentation.suse.com Copyright © 2006– 2021 SUSE LLC and contributors. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or (at your option) version 1.3; with the Invariant Section being this copyright notice and license. A copy of the license version 1.2 is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. For SUSE trademarks, see https://www.suse.com/company/legal/ . All other third-party trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Trademark symbols (®, ™ etc.) denote trademarks of SUSE and its aliates. Asterisks (*) denote third-party trademarks. All information found in this book has been compiled with utmost attention to detail. However, this does not guarantee complete accuracy. Neither SUSE LLC, its aliates, the authors nor the translators shall be held liable for possible errors or the consequences thereof. Contents About This Guide xii 1 Available Documentation xiii -

Linux Command Line: Aliases, Prompts and Scripting

Linux Command Line: Aliases, Prompts and Scri... 1 Linux Command Line: Aliases, Prompts and Scripting By Steven Gordon on Wed, 23/07/2014 - 7:46am Here are a few notes on using the Bash shell that I have used as a demo to students. It covers man pages, aliases, shell prompts, paths and basics of shell scripting. For details, see the many free manuals of Bash shell scripting. 1. Man Pages Man pages are the reference manuals for commands. Reading the man pages is best when you know the command to use, but cannot remember the syntax or options. Simply type man cmd and then read the manual. E.g.: student@netlab01:~$ man ls If you don't know which command to use to perform some task, then there is a basic search feature called apropos which will do a keyword search through an index of man page names and short descriptions. You can run it using either the command apropos or using man -k. E.g.: student@netlab01:~$ man superuser No manual entry for superuser student@netlab01:~$ apropos superuser su (1) - change user ID or become superuser student@netlab01:~$ man -k "new user" newusers (8) - update and create new users in batch useradd (8) - create a new user or update default new user information Some common used commands are actually not standalone program, but commands built-in to the shell. For example, below demonstrates the creation of aliases using alias. But there is no man page for alias. Instead, alias is described as part of the bash shell man page. -

Uulity Programs and Scripts

U"lity programs and scripts Thomas Herring [email protected] U"lity Overview • In this lecture we look at a number of u"lity scripts and programs used in the gamit/globk suite of programs. • We examine and will show examples in the areas of – Organizaon/Pre-processing – Scripts used by sh_gamit but useful stand-alone – Evaluang results • Also examine some basic unix, csh, bash programs and method. 11/19/12 Uli"es Lec 08 2 Guide to scripts • There are many scripts in the ~/gg/com directory and you should with "me looks at all these scripts because they oSen contain useful guides as to how to do certain tasks. – Look the programs used in the scripts because these show you the sequences and inputs needed for different tasks – Scrip"ng methods are useful when you want to automate tasks or allow easy re-generaon of results. – Look for templates that show how different tasks can be accomplished. • ~/gg/kf/uls and ~/gg/gamit/uls contain many programs for u"lity tasks and these should be looked at to see what is available. 11/19/12 Uli"es Lec 08 3 GAMIT/GLOBK Utilities" 1.! Organization/Pre-processing" sh_get_times: List start/stop times for all RINEX files" sh_upd_stnfo: Add entries to station.info from RINEX headers" convertc: Transform coodinates (cartesian/geodetic/spherical)" glist: List sites for h-files in gdl; check coordinates, models " corcom: Rotate an apr file to a different plate frame" unify_apr: Set equal velocities/coordinates for glorg equates" sh_dos2unix: Remove the extra CR from each line of a file" doy: Convert to/from DOY, YYMMDD, JD, MJD, GPSW" " " " GAMIT/GLOBK Utilities (cont)" 2. -

Unix Login Profile

Unix login Profile A general discussion of shell processes, shell scripts, shell functions and aliases is a natural lead in for examining the characteristics of the login profile. The term “shell” is used to describe the command interpreter that a user runs to interact with the Unix operating system. When you login, a shell process is initiated for you, called your login shell. There are a number of "standard" command interpreters available on most Unix systems. On the UNF system, the default command interpreter is the Korn shell which is determined by the user’s entry in the /etc/passwd file. From within the login environment, the user can run Unix commands, which are just predefined processes, most of which are within the system directory named /usr/bin. A shell script is just a file of commands, normally executed at startup for a shell process that was spawned to run the script. The contents of this file can just be ordinary commands as would be entered at the command prompt, but all standard command interpreters also support a scripting language to provide control flow and other capabilities analogous to those of high level languages. A shell function is like a shell script in its use of commands and the scripting language, but it is maintained in the active shell, rather than in a file. The typically used definition syntax is: <function-name> () { <commands> } It is important to remember that a shell function only applies within the shell in which it is defined (not its children). Functions are usually defined within a shell script, but may also be entered directly at the command prompt. -

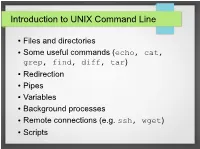

Introduction to UNIX Command Line

Introduction to UNIX Command Line ● Files and directories ● Some useful commands (echo, cat, grep, find, diff, tar) ● Redirection ● Pipes ● Variables ● Background processes ● Remote connections (e.g. ssh, wget) ● Scripts The Command Line ● What is it? ● An interface to UNIX ● You type commands, things happen ● Also referred to as a “shell” ● We'll use the bash shell – check you're using it by typing (you'll see what this means later): ● echo $SHELL ● If it doesn't say “bash”, then type bash to get into the bash shell Files and Directories / home var usr mcuser abenson drmentor science catvideos stuff data code report M51.fits simulate.c analyze.py report.tex Files and Directories ● Get a pre-made set of directories and files to work with ● We'll talk about what these commands do later ● The “$” is the command prompt (yours might differ). Type what's listed after hit, then press enter. $$ wgetwget http://bit.ly/1TXIZSJhttp://bit.ly/1TXIZSJ -O-O playground.tarplayground.tar $$ tartar xvfxvf playground.tarplayground.tar Files and directories $$ pwdpwd /home/abenson/home/abenson $$ cdcd playgroundplayground $$ pwdpwd /home/abenson/playground/home/abenson/playground $$ lsls animalsanimals documentsdocuments sciencescience $$ mkdirmkdir mystuffmystuff $$ lsls animalsanimals documentsdocuments mystuffmystuff sciencescience $$ cdcd animals/mammalsanimals/mammals $$ lsls badger.txtbadger.txt porcupine.txtporcupine.txt $$ lsls -l-l totaltotal 88 -rw-r--r--.-rw-r--r--. 11 abensonabenson abensonabenson 19441944 MayMay 3131 18:0318:03 badger.txtbadger.txt -rw-r--r--.-rw-r--r--. 11 abensonabenson abensonabenson 13471347 MayMay 3131 18:0518:05 porcupine.txtporcupine.txt Files and directories “Present Working Directory” $$ pwdpwd Shows the full path of your current /home/abenson/home/abenson location in the filesystem. -

Linux/Unix: the Command Line

Linux/Unix: The Command Line Adapted from materials by Dan Hood Essentials of Linux • Kernel ú Allocates time and memory, handles file operations and system calls. • Shell ú An interface between the user and the kernel. • File System ú Groups all files together in a hierarchical tree structure. 2 Format of UNIX Commands • UNIX commands can be very simple one word commands, or they can take a number of additional arguments (parameters) as part of the command. In general, a UNIX command has the following form: command options(s) filename(s) • The command is the name of the utility or program that we are going to execute. • The options modify the way the command works. It is typical for these options to have be a hyphen followed by a single character, such as -a. It is also a common convention under Linux to have options that are in the form of 2 hyphens followed by a word or hyphenated words, such as --color or --pretty-print. • The filename is the last argument for a lot of UNIX commands. It is simply the file or files that you want the command to work on. Not all commands work on files, such as ssh, which takes the name of a host as its argument. Common UNIX Conventions • In UNIX, the command is almost always entered in all lowercase characters. • Typically any options come before filenames. • Many times, individual options may need a word after them to designate some additional meaning to the command. Familiar Commands: scp (Secure CoPy) • The scp command is a way to copy files back and forth between multiple computers.