LOCUS FOCUS Forum of the Sussex Place-Names Net

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN SUSSEX ARTHUR STANLEY COOKE Witti One Hundred and Sixty Illustrations by Sussex Artists

OFF THE BEATEN TRACK IN SUSSEX ARTHUR STANLEY COOKE Witti one Hundred and sixty illustrations by Sussex artists :LO ICNJ :LT> 'CO CD CO OFF THE BEATEN TRACK IN SUSSEX BEEDING LEVEL. (By Fred Davey ) THE GATEWAY, MICHELHAM PRIORY (page 316). (By .4. S. C.) OFF THE BEATEN TRACK IN SUSSEX BY ARTHUR STANLEY COOKE WITH ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY ILLUSTRATIONS BY SUSSEX ARTISTS IN CUCKFIELD PARK (By Walter Puttick.) HERBERT JENKINS LIMITED 3 YORK STREET LONDON S.W. i A HERBERT JENKINS' BOOK Printed in Great Britain by Wyman & Sons Ltd., London, Reading and Fakenham, BOSHAM (page 176). (By Hubert Schroder, A.R.E.) PREFACE this volume tends to make our varied and beautiful county " " better known, it shall do well especially if it gives pleasure to those unable to take such walks. If it has, IF here and there, a thought or an idea not generally obvious, it may perhaps be forgiven the repetitions which are inevitable in describing similar details forgiven the recital of familiar facts, whether historical, archaeological or natural forgiven, where, by the light of later or expert knowledge, errors are apparent. Some of these blemishes are consequent on the passage of time necessary to cover so large an area by frequent personal visitation. Some thirty-seven rambles are described, about equally divided between the east and west divisions of the county. Although indications of route are given, chiefly for the benefit of strangers, it does not claim to be a guide-book. Its size would preclude such a use. Neither does it pretend to be exhaustive. -

The Ballad/Alan Bold Methuen & Co

In the same series Tragedy Clifford Leech Romanticism Lilian R Furst Aestheticism R. V. Johnson The Conceit K. K Ruthven The Ballad/Alan Bold The Absurd Arnold P. Hinchliffe Fancy and Imagination R. L. Brett Satire Arthur Pollard Metre, Rhyme and Free Verse G. S. Fraser Realism Damian Grant The Romance Gillian Beer Drama and the Dramatic S W. Dawson Plot Elizabeth Dipple Irony D. C Muecke Allegory John MacQueen Pastoral P. V. Marinelli Symbolism Charles Chadwick The Epic Paul Merchant Naturalism Lilian R. Furst and Peter N. Skrine Rhetoric Peter Dixon Primitivism Michael Bell Comedy Moelwyn Merchant Burlesque John D- Jump Dada and Surrealism C. W. E. Bigsby The Grotesque Philip Thomson Metaphor Terence Hawkes The Sonnet John Fuller Classicism Dominique Secretan Melodrama James Smith Expressionism R. S. Furness The Ode John D. Jump Myth R K. Ruthven Modernism Peter Faulkner The Picaresque Harry Sieber Biography Alan Shelston Dramatic Monologue Alan Sinfield Modern Verse Drama Arnold P- Hinchliffe The Short Story Ian Reid The Stanza Ernst Haublein Farce Jessica Milner Davis Comedy of Manners David L. Hirst Methuen & Co Ltd 19-+9 xaverslty. Librasü Style of the ballads 21 is the result not of a literary progression of innovators and their acolytes but of the evolution of a form that could be men- 2 tally absorbed by practitioners of an oral idiom made for the memory. To survive, the ballad had to have a repertoire of mnemonic devices. Ballad singers knew not one but a whole Style of the ballads host of ballads (Mrs Brown of Falkland knew thirty-three separate ballads). -

Seaward Sussex - the South Downs from End to End

Seaward Sussex - The South Downs from End to End Edric Holmes The Project Gutenberg EBook of Seaward Sussex, by Edric Holmes This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Seaward Sussex The South Downs from End to End Author: Edric Holmes Release Date: June 11, 2004 [EBook #12585] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SEAWARD SUSSEX *** Produced by Dave Morgan, Beth Trapaga and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. [Illustration: HURSTMONCEUX.] SEAWARD SUSSEX THE SOUTH DOWNS FROM END TO END BY EDRIC HOLMES ONE HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARY M. VIGERS MAPS AND PLANS BY THE AUTHOR LONDON: ROBERT SCOTT ROXBURGHE HOUSE PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. MCMXX "How shall I tell you of the freedom of the Downs-- You who love the dusty life and durance of great towns, And think the only flowers that please embroider ladies' gowns-- How shall I tell you ..." EDWARD WYNDHAM TEMPEST. Every writer on Sussex must be indebted more or less to the researches and to the archaeological knowledge of the first serious historian of the county, M.A. Lower. I tender to his memory and also to his successors, who have been at one time or another the good companions of the way, my grateful thanks for what they have taught me of things beautiful and precious in Seaward Sussex. -

OETZMANN & CO., Ltd F WE

EASTBOURNE, SATURDi|f, JUNE '2 2 , 1918. J^ASTBOURNE C O L L s ;g e H|E LADIES’ COLLEGE MARY H. COOPER, Court Dressmaker. T AND KINDERGARTEN, President t G^tASSINGTON ROAD, EASTBOURNE. BEUFOED& SON, THE DUKE O f DEVONSHIRE COAT DRESSES, SUITS & RESTAURANT GOWNS for Spring Wear. A Day School for the Daughters Watchmakers, 9. B. W TT.LTAM S, M .A . Principal: M ISS HITCHCOCK. Tele. 7«3. 6, IilSMOBE BO AD, EASTBOURNE. P upils prepared, if desired, for the Prelim inary. Junior, JEWELLERS & S] LVERSM1THS Senior and H igher C am bridge Local Exam inations, also -fcrioulatlon London U nlverslt ‘ BEST VM.UK.] SCHOOL for the Bom ation by the A ssociated Boai (P roprietors, dem y of M usic and R oyal Colli QUALITY GUARANTEED. A N D B og prepared CorJbaU nlTenltlM , the A nar. N avy desirous of pursuing th eir studies af tier leaving Bra’ ' Command D e p d t DICKER CO. E. & F. SLOOOMBE), n d CR t B B errlm s, Pnfeeelons and O am m eroial Life. illegal use of petrol Join A dvanced C lasses I d English L iterature Repairs bp Expert Men. ~ T here ere tpeatal A b e t a n d N a v t C l a j w s s . French, Italian. L atin, M att em atlcs. Singing, & e.. ndant alighted from a HIGH-CLASS PROVISION MERCHANTS AND GROCERS, F o r P roepeottu and Inform ation ae to recent Buooeeeee. rive and walked up a , 100, Terminus-rd., Eastbourne appilotW on should be m ade to the H e a d M a b t t o . -

Mcalpine (1995)

ýýesi. s ayoS THE GALLOWS AND THE STAKE: A CONSIDERATION OF FACT AND FICTION IN THE SCOTTISH BALLADS FOR MY PARENTS AND IN MEMORY OF NAN ANDERSON, WHO ALMOST SAW THIS COMPLETED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before embarking on the subject of hanging and burning, I would like to linger for a moment on a much more pleasant topic and to take this opportunity to thank everyone who has helped me in the course of my research. Primarily, thanks goes to all my supervisors, most especially to Emily Lyle of the School of Scottish Studies and to Douglas Mack of Stirling, for their support, their willingness to read through what must have seemed like an interminable catalogue of death and destruction, and most of all for their patience. I also extend thanks to Donald Low and Valerie Allen, who supervised the early stages of this study. Three other people whom I would like to take this opportunity to thank are John Morris, Brian Moffat and Stuart Allan. John Morris provided invaluable insight into Scottish printed balladry and I thank him for showing the Roseberry Collection to me, especially'The Last Words of James Mackpherson Murderer'. Brian Moffat, armourer and ordnancer, was a fount of knowledge on Border raiding tactics and historical matters of the Scottish Middle and West Marches and was happy to explain the smallest points of geographic location - for which I am grateful: anyone who has been on the Border moors in less than clement weather will understand. Stuart Allan of the Historic Search Room, General Register House, also deserves thanks for locating various documents and papers for me and for bringing others to my attention: in being 'one step ahead', he reduced my workload as well as his own. -

Consultation Statement (Regulation 22) Statement of Consultation

Submission City Plan Part One June 2013 Consultation Statement (Regulation 22) Statement of Consultation Statement of Representations Made and Main Issues Raised (Regulation 22(1) (c) (v) and (d) of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................3 1.1 Role of the Document .....................................................................................3 1.2 Compliance with Statement of Community Involvement.................................3 2. Consultation on the City Plan Part 1 ........................................................................4 2.1 Background.....................................................................................................4 2.2 Proposed Submission City Plan Part 1 ...........................................................4 When the Proposed Submission Plan was Published..................................................4 The Proposed Submission Documents........................................................................5 Where the documents were made available ................................................................6 Notification of Publication.............................................................................................6 Media ...........................................................................................................................7 3. The Number of Representations made under Regulation 22...................................8 -

A Book of Old Ballads

ECLECTIC ENGLISH CLASSICS A BOOK OF O LD BALLAD S EDITED BY O R A /l O RTO N M A C {t , . NORWOOD HIGH SCHOOL NOR O W OD, OHIO AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY NEW YO RK PRE FACE £ 9 T h rs a reed o a eac e of English are generally g that the—l gic l t im e t o use ballads is in the early adolescent period in the l n of first years of the high school , or perhaps the last year the { — grammar grades yet the st andard ballad anthologies are t oo f m l o full and too unsifted or such use . Fro these larger col ecti ns not only the best known and the most typical examples have been chosen but also the best version of each . As the ballads were unwritten in the beginning and were m for m o n orally trans itted any generati ns , the spelli g of the fif f early manuscripts is the spelling of the transcriber. The t eent h and sixteenth century ballad lovers knew the sounds Of wo nl o m the rds o y, and the written f r s in which they have been preserved are merely makeshift devices for visualizing m n t he m o . th se sounds The ore u obtrusive akeshift, the less is o m the attenti n distracted fro the sound and the sense, and the nearer are we to receiving the story as the early listeners m r in received it . For this reason fa iliar wo ds the ballads in this book are printed in the familiar spelling of to- day except where rhyme or rhythm demanded the retention of an older m of a for . -

Seaward Sussex

Seaward Sussex By Edric Holmes Seaward Sussex CHAPTER I LEWES "Lewes is the most romantic situation I ever saw"; thus Defoe, and the capital of Sussex shares with Rye and Arundel the distinction of having a continental picturesqueness more in keeping with old France than with one of the home counties of England. This, however, is only the impression made by the town when viewed as a whole; its individual houses, its churches and castle, and above all, its encircling hills are England, and England at her best and dearest to those who call Sussex home. The beauty of the surroundings when viewed from almost any of its old world streets and the charm of the streets themselves make the old town an ever fresh and welcome resort for the tired Londoner who appreciates a quiet holiday. As a centre for the exploration of East Sussex Lewes has no equal; days may be spent before the interest of the immediate neighbourhood is exhausted; for those who are vigorous enough for hill rambling the paths over the Downs are dry and passable in all weathers, and the Downs themselves, even apart from the added interest of ancient church or picturesque farm and manor, are ample recompense for the small toil involved in their exploration. The origin of Lewes goes back to unknown times, the very meaning of the name is lost, its situation in a pass and on the banks of the only navigable river in East Sussex inevitably made it a place of some importance. It is known that Athelstan had two mints here and that the Norman Castle was only a rebuilding by William de Warenne on the site of a far older stronghold. -

Seaward Sussex - the South Downs from End to End

Seaward Sussex - The South Downs from End to End Edric Holmes The Project Gutenberg EBook of Seaward Sussex, by Edric Holmes This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Seaward Sussex The South Downs from End to End Author: Edric Holmes Release Date: June 11, 2004 [EBook #12585] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SEAWARD SUSSEX *** Produced by Dave Morgan, Beth Trapaga and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. [Illustration: HURSTMONCEUX.] SEAWARD SUSSEX THE SOUTH DOWNS FROM END TO END BY EDRIC HOLMES ONE HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARY M. VIGERS MAPS AND PLANS BY THE AUTHOR Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. LONDON: ROBERT SCOTT ROXBURGHE HOUSE PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. MCMXX "How shall I tell you of the freedom of the Downs-- You who love the dusty life and durance of great towns, And think the only flowers that please embroider ladies' gowns-- How shall I tell you ..." EDWARD WYNDHAM TEMPEST. Every writer on Sussex must be indebted more or less to the researches and to the archaeological knowledge of the first serious historian of the county, M.A. Lower. I tender to his memory and also to his successors, who have been at one time or another the good companions of the way, my grateful thanks for what they have taught me of things beautiful and precious in Seaward Sussex. -

Poetic Origins and the Ballad

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications -- Department of English English, Department of January 1921 Poetic Origins and the Ballad Louise Pound University of Nebraska Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Pound, Louise, "Poetic Origins and the Ballad" (1921). Faculty Publications -- Department of English. 43. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs/43 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications -- Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. POETIC ORIGINS AND THE BALLAD BY LOUISE POUND, Ph.D. Professor of English in the University of Nebraska )Sew ~Otft THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1921 aU riuhta reserved COPYRIGHT, 1921, By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up and electrotyped. Published, January, 1921. TO HARTLEY AND NELLIE ALEXANDER PREFACE The leading theses of the present volume are that the following assumptions which have long dominated our thought upon the subject of poetic origins and the ballads should be given up, or at least should be seriously quali fied; namely, belief in the "communal" authorship and ownership of primitive poetry; disbelief in the primitive artist; reference to the ballad as the earliest and most universal poetic form; belief in the origin of narrative -

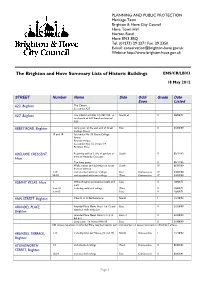

The Brighton and Hove Summary Lists of Historic Buildings ENS/CR/LB/03

PLANNING AND PUBLIC PROTECTION Heritage Team Brighton & Hove City Council Hove Town Hall Norton Road Hove BN3 3BQ Tel: (01273) 29 2271 Fax: 29 2350 E-mail: [email protected] Website http://www.brighton-hove.gov.uk The Brighton and Hove Summary Lists of Historic Buildings ENS/CR/LB/03 18 May 2012 STREET Number Name Side Odd/ Grade Date Even Listed The Chattri, A23, Brighton See under A27 A27, Brighton The Chattri at NGR TQ 304 103, on North of II 20/08/71 land north of A27 Road and east of A23 Lamp post at the east end of Great East II 26/08/99 ABBEY ROAD, Brighton College Street 17 and 19 See under No. 53 Great College Street Pearson House See under Nos 12, 13 and 14 Portland Place Retaining wall to S side of gardens in South II 02/11/92 ADELAIDE CRESCENT, front of Adelaide Crescent Hove Ten lamp posts II 02/11/92 Walls, ramps and stairways on South South II* 05/05/69 front of terrace 1-19 and attached walls and railings East Consecutive II* 24/03/50 20-38 and attached walls and railings West Consecutive II* 24/03/50 1 White Knights and attached walls and East II 10/09/71 ALBANY VILLAS, Hove piers 2 and 4 including walls and railings West II 10/09/71 3 and 5 East II 10/09/71 Church of St Bartholomew North I 13/10/52 ANN STREET, Brighton Arundel Place Mews Nos.11 & 12 and East II 26/08/99 ARUNDEL PLACE, attached walls and piers Brighton Arundel Place Mews Units 2, 3, 4, 8, East of II 26/08/99 8A & 9 Lamp post - in front of No.10 East II 26/08/99 NB some properties on Arundel Place may be listed as part of properties on Lewes Crescent or Arundel Terrace. -

Mattins and Mutton's

00097541 Digitized with financial assistance from the Government of Maharashtra on 02 July, 2018 MATIINB AND MUTTON’S: OE, I THE OE .HIHGHTON. ^ % i ’obe ^ o r n . S 7541^ jiy Ct'j'ITBEirr BEDE. ^ muoK 01 ■ r«w’,.r : ■ » .■. lmi am > jitAunn . • •T.. KJ{, »rc. A" 0 L . 1 1 . K?55y ' • ■ ■ » ■ - R ^ ■■f p 'f \ L ( * N D O > : : f t ^A-'D»80N i;0\V', s o x , \.x d marston. MIi.T'iX IK jI M;, l i '. '. I I . 11I,L IK.,1, 0''V t <■’' rr ■» 1 ^ON’TH):^: I’RrHTKD UY WOOnrALL A'.D KIN * 1, U IU O & U L iL 'ir, ATICAND, WM. 00097541 00097541 « ♦ CONTENTS OF TOL. 11. »•> CHAP. PA(JK 1 I. E v en so n AI . II. T h e E n d BATniNG-M.vciiiNE . o . I S III. A D u iv e a n d a L e t t e r . :iti IV. ^ t i s s P e t t u ' e h ’s G r i n o u n f , . 5 2 V. T h e G h o s t o f C l i f f P l a c e Ci7 VI. A t t h e P a v il io n . ? 2 VII. U n d e r t h e E l m s .... im VIII. A G a l l o f o n t h e D o w n s . ,/ 1 1 5 IX. M r s . G r im s b y G r o u t ' s E n t e r t .a t n m e n i .