Melianthus Major L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa Cape Wildflowers, Birding & Big Game II 21St August to 3Rd September 2022 (14 Days)

South Africa Cape Wildflowers, Birding & Big Game II 21st August to 3rd September 2022 (14 days) Cape Mountain Zebras & wildflowers in West Coast NP by Adam Riley This comprehensive tour covers the most exciting regions of the Cape in our quest to experience both breathtaking displays of wildflowers and to track down some of the country’s endemic birds. We begin in the vibrant city of Cape Town, where Table Mountain provides a spectacular backdrop to the immensely diverse fynbos that cloaks the cities periphery. This fynbos constitutes the Cape Floral Kingdom – the smallest and richest of the world’s 6 floral kingdoms. It is also the only floral kingdom to be confined to the boundaries of a single country. Thereafter we venture to the West Coast and Namaqualand, which boast an outrageous and world famous floral display in years of good rains, before travelling through the heart of the country’s semi-desert region, focusing on the special bird’s endemic to this ancient landscape. We conclude the journey heading out of wildflower country to Augrabies Falls, an area offering unparalleled raptor viewing and a wide range of dry region birds. We invite you on this celebration of some of the finest wildflower and endemic birding that the African continent has to offer! RBT South Africa - Cape Wildflowers, Birding & Big Game 2 THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Upington Day 2 Upington to Augrabies Falls National Park Day 3 Augrabies Falls National Park Day 4 Augrabies Falls National Park to Springbok Day 5 Springbok to Nieuwoudtville -

Arthur Monrad Johnson Colletion of Botanical Drawings

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7489r5rb No online items Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Processed by Pat L. Walter. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division History and Special Collections Division UCLA 12-077 Center for Health Sciences Box 951798 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1798 Phone: 310/825-6940 Fax: 310/825-0465 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/biomed/his/ ©2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion 48 1 of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Descriptive Summary Title: Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings, Date (inclusive): 1914-1941 Collection number: 48 Creator: Johnson, Arthur Monrad 1878-1943 Extent: 3 boxes (2.5 linear feet) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: Approximately 1000 botanical drawings, most in pen and black ink on paper, of the structural parts of angiosperms and some gymnosperms, by Arthur Monrad Johnson. Many of the illustrations have been published in the author's scientific publications, such as his "Taxonomy of the Flowering Plants" and articles on the genus Saxifraga. Dr. Johnson was both a respected botanist and an accomplished artist beyond his botanical subjects. Physical location: Collection stored off-site (Southern Regional Library Facility): Advance notice required for access. Language of Material: Collection materials in English Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings (Manuscript collection 48). Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division, University of California, Los Angeles. -

Alphabetical Lists of the Vascular Plant Families with Their Phylogenetic

Colligo 2 (1) : 3-10 BOTANIQUE Alphabetical lists of the vascular plant families with their phylogenetic classification numbers Listes alphabétiques des familles de plantes vasculaires avec leurs numéros de classement phylogénétique FRÉDÉRIC DANET* *Mairie de Lyon, Espaces verts, Jardin botanique, Herbier, 69205 Lyon cedex 01, France - [email protected] Citation : Danet F., 2019. Alphabetical lists of the vascular plant families with their phylogenetic classification numbers. Colligo, 2(1) : 3- 10. https://perma.cc/2WFD-A2A7 KEY-WORDS Angiosperms family arrangement Summary: This paper provides, for herbarium cura- Gymnosperms Classification tors, the alphabetical lists of the recognized families Pteridophytes APG system in pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms Ferns PPG system with their phylogenetic classification numbers. Lycophytes phylogeny Herbarium MOTS-CLÉS Angiospermes rangement des familles Résumé : Cet article produit, pour les conservateurs Gymnospermes Classification d’herbier, les listes alphabétiques des familles recon- Ptéridophytes système APG nues pour les ptéridophytes, les gymnospermes et Fougères système PPG les angiospermes avec leurs numéros de classement Lycophytes phylogénie phylogénétique. Herbier Introduction These alphabetical lists have been established for the systems of A.-L de Jussieu, A.-P. de Can- The organization of herbarium collections con- dolle, Bentham & Hooker, etc. that are still used sists in arranging the specimens logically to in the management of historical herbaria find and reclassify them easily in the appro- whose original classification is voluntarily pre- priate storage units. In the vascular plant col- served. lections, commonly used methods are systema- Recent classification systems based on molecu- tic classification, alphabetical classification, or lar phylogenies have developed, and herbaria combinations of both. -

Nhs Fall Plant Sale Friday, September 18, Noon to 6:30 Pm Saturday, September 19, 9:00 Am to 3:00 Pm

ardennotes northwestG horticultural society fall 2009 nhs fall plant sale friday, september 18, noon to 6:30 pm saturday, september 19, 9:00 am to 3:00 pm L ISA IRWIN CLEAR THE DE C KS ! CLEAR THE BEDS ! Throw out those under-performers (your plants, not your spouses) and join us for the Fall Plant Sale on September 18 and 19 at Magnuson Park in Seattle. Even if you don’t think you have room for another plant, come see what’s new that you can’t do without. This year we will have more than 30 outstanding specialty growers from around the Puget Sound area to dazzle you with their wide variety of plants. Fall is a great time for planting. As the temperatures lessen and the rains begin, plants have a much easier time developing root growth. When spring finally comes the plants will be well on their way. We expect a good selection Oh la la! Ciscoe Morris is all ready for the NHS fall plant sale. of plants that will not only benefit from See related articles on pages 1-4. (Nita-Jo Rountree) fall planting, but many that will provide an awesome fall display. Far Reaches include Melianthus villosa, of my favorite vendors for fabulous Kelly and Sue of Far Reaches and Bergenia ‘Eric Smith’. epimedium, cyclamen, hosta, and Farm will be bringing some exotic Laine McLauglin of Steamboat polygonatum are Naylor Creek plants from Yunnan. Salvia bulleyana Island Nursery has recently stopped Nursery, Bouquet Banque Nursery, has large broadly deltoid two-tone her retail sales at the nursery to Botanica, and Overland Enterprises. -

Biodiversity and Ecology of Critically Endangered, Rûens Silcrete Renosterveld in the Buffeljagsrivier Area, Swellendam

Biodiversity and Ecology of Critically Endangered, Rûens Silcrete Renosterveld in the Buffeljagsrivier area, Swellendam by Johannes Philippus Groenewald Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Science in Conservation Ecology in the Faculty of AgriSciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Michael J. Samways Co-supervisor: Dr. Ruan Veldtman December 2014 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration I hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis, for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Ecology, is my own work that have not been previously published in full or in part at any other University. All work that are not my own, are acknowledge in the thesis. ___________________ Date: ____________ Groenewald J.P. Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Acknowledgements Firstly I want to thank my supervisor Prof. M. J. Samways for his guidance and patience through the years and my co-supervisor Dr. R. Veldtman for his help the past few years. This project would not have been possible without the help of Prof. H. Geertsema, who helped me with the identification of the Lepidoptera and other insect caught in the study area. Also want to thank Dr. K. Oberlander for the help with the identification of the Oxalis species found in the study area and Flora Cameron from CREW with the identification of some of the special plants growing in the area. I further express my gratitude to Dr. Odette Curtis from the Overberg Renosterveld Project, who helped with the identification of the rare species found in the study area as well as information about grazing and burning of Renosterveld. -

SIGCHI Conference Paper Format

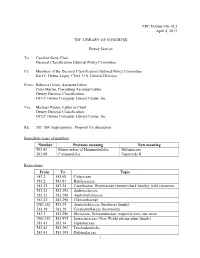

EPC Exhibit 136-19.2 April 4, 2013 THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Dewey Section To: Caroline Kent, Chair Decimal Classification Editorial Policy Committee Cc: Members of the Decimal Classification Editorial Policy Committee Karl E. Debus-López, Chief, U.S. General Division From: Rebecca Green, Assistant Editor Giles Martin, Consulting Assistant Editor Dewey Decimal Classification OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. Via: Michael Panzer, Editor in Chief Dewey Decimal Classification OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc Re: 583–584 Angiosperms: Proposal for discussion Immediate reuse of numbers Number Previous meaning New meaning 583.43 Minor orders of Hamamelididae Dilleniaceae 583.98 Campanulales Euasterids II Relocations From To Topic 583.2 583.68 Cytinaceae 583.2 583.83 Rafflesiaceae 583.22 583.24 Canellaceae, Winteraceae (winter's bark family), wild cinnamon 583.23 583.292 Amborellaceae 583.23 583.296 Austrobaileyaceae 583.23 583.298 Chloranthaceae [583.26] 583.25 Aristolochiaceae (birthwort family) 583.29 583.28 Ceratophyllaceae (hornworts) 583.3 583.296 Illiciaceae, Schisandraceae, magnolia vine, star anise [583.36] 583.975 Sarraceniaceae (New World pitcher plant family) 583.43 583.34 Eupteleaceae 583.43 583.393 Trochodendrales 583.43 583.395 Didymelaceae 1 583.43 583.44 Cercidiphyllaceae (katsura trees) 583.43 583.46 Casuarinaceae (beefwoods), Myricaceae (wax myrtles), bayberries, candleberry, sweet gale (bog myrtle) 583.43 583.73 Barbeyaceae 583.43 583.786 Leitneria 583.43 583.83 Balanopaceae 583.43 583.942 Eucommiaceae 583.44 -

Calibrated Chronograms, Fossils, Outgroup Relationships, and Root Priors: Re-Examining the Historical Biogeography of Geraniales

bs_bs_banner Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2014, 113, 29–49. With 4 figures Calibrated chronograms, fossils, outgroup relationships, and root priors: re-examining the historical biogeography of Geraniales KENNETH J. SYTSMA1,*, DANIEL SPALINK1 and BRENT BERGER2 1Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA 2Department of Biological Sciences, St. John’s University, Queens, NY 11439, USA Received 26 November 2013; revised 23 February 2014; accepted for publication 24 February 2014 We re-examined the recent study by Palazzesi et al., (2012) published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society (107: 67–85), that presented the historical diversification of Geraniales using BEAST analysis of the plastid spacer trnL–F and of the non-coding nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacers (ITS). Their study presented a set of new fossils within the order, generated a chronogram for Geraniales and other rosid orders using fossil-based priors on five nodes, demonstrated an Eocene radiation of Geraniales (and other rosid orders), and argued for more recent (Pliocene–Pleistocene) and climate-linked diversification of genera in the five recognized families relative to previous studies. As a result of very young ages for the crown of Geraniales and other rosid orders, unusual relationships of Geraniales to other rosids, and apparent nucleotide substitution saturation of the two gene regions, we conducted a broad series of BEAST analyses that incorporated additional rosid fossil priors, used more accepted rosid ordinal -

Crocosmia X Crocosmiiflora Montbretia Crocosmia Aurea X Crocosmia Pottsii – Naturally Occurring Hybrid

Top 40 Far Flung Flora A selection of the best plants for pollinators from the Southern Hemisphere List Curated by Thomas McBride From research data collected and collated at the National Botanic Garden of Wales NB: Butterflies and Moths are not studied at the NBGW so any data on nectar plants beneficial for them is taken from Butterfly Conservation The Southern Hemisphere Verbena bonariensis The Southern Hemisphere includes all countries below the equator. As such, those countries are the furthest from the UK and tend to have more exotic and unusual native species. Many of these species cannot be grown in the UK, but in slightly more temperate regions, some species will thrive here and be of great benefit to our native pollinators. One such example is Verbena bonariensis, native to South America, which is a big hit with our native butterfly and bumblebee species. The Southern Hemisphere contains a lower percentage of land than the northern Hemisphere so the areas included are most of South America (particularly Chile, Argentina, Ecuador and Peru), Southern Africa (particularly South Africa) and Oceania (Particularly Australia and New Zealand). A large proportion of the plants in this list are fully hardy in the UK but some are only half-hardy. Half-hardy annuals may be planted out in the spring and will flourish. Half-hardy perennials or shrubs may need to be grown in pots and moved indoors during the winter months or grown in a very sheltered location. The plants are grouped by Tropaeolum majus Continent rather than a full alphabetical -

Updated Angiosperm Family Tree for Analyzing Phylogenetic Diversity and Community Structure

Acta Botanica Brasilica - 31(2): 191-198. April-June 2017. doi: 10.1590/0102-33062016abb0306 Updated angiosperm family tree for analyzing phylogenetic diversity and community structure Markus Gastauer1,2* and João Augusto Alves Meira-Neto2 Received: August 19, 2016 Accepted: March 3, 2017 . ABSTRACT Th e computation of phylogenetic diversity and phylogenetic community structure demands an accurately calibrated, high-resolution phylogeny, which refl ects current knowledge regarding diversifi cation within the group of interest. Herein we present the angiosperm phylogeny R20160415.new, which is based on the topology proposed by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV, a recently released compilation of angiosperm diversifi cation. R20160415.new is calibratable by diff erent sets of recently published estimates of mean node ages. Its application for the computation of phylogenetic diversity and/or phylogenetic community structure is straightforward and ensures the inclusion of up-to-date information in user specifi c applications, as long as users are familiar with the pitfalls of such hand- made supertrees. Keywords: angiosperm diversifi cation, APG IV, community tree calibration, megatrees, phylogenetic topology phylogeny comprising the entire taxonomic group under Introduction study (Gastauer & Meira-Neto 2013). Th e constant increase in knowledge about the phylogenetic The phylogenetic structure of a biological community relationships among taxa (e.g., Cox et al. 2014) requires regular determines whether species that coexist within a given revision of applied phylogenies in order to incorporate novel data community are more closely related than expected by chance, and is essential information for investigating and avoid out-dated information in analyses of phylogenetic community assembly rules (Kembel & Hubbell 2006; diversity and community structure. -

Honeybush, Melianthus Major

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 26 Feb 2016 Honeybush, Melianthus major One of six species in the genus, Melianthus major is an evergreen shrub in the family Melianthaceae native to drier areas of the southwestern Cape in South Africa. It is easy to grow, so has been used as a garden plant worldwide for its attractive foliage. With large blue, deeply incised leaves, honeybush makes a dramatic addition to containers or seasonal plantings. Although it is only hardy to zone 8, it is fast-growing so can be used as seasonal ornamental in colder areas. In the wild it is a winter grower, going dormant in the summer, but will grow Melianthus major is a tender shrub grown well in the relatively cool for its attractive foliage. summers of the Midwest. Honeybush received the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit in 1993. Honeybush is used as a seasonal ornamental in cool climates. In its native habitat or other mild climates honeybush grows up to 10 feet tall and spreads by suckering roots (and has become an invasive plant in some areas, such as parts of New Zealand). It is naturally a sparsely branched shrub with a sprawling habit. But it looks best when pruned hard and is often treated more like a perennial than a Melianthus major in habitat in the Cedarberg Mountains shrub when near Clanwilliam, South Africa. used as an ornamental. When grown as an annual seasonally in cold climates it remains much shorter, but the leaves are still as large. -

RHS Seed Exchange 2020

RHS Seed Exchange rhs.org.uk/seedlist Introduction to RHS Seed Exchange 2121 The Royal Horticultural Society is the UK’s Dispatch of Orders leading gardening charity, which aims to enrich We will start to send out orders from January everyone’s life through plants, and make the UK a 2020 and dispatch is usually completed by the greener and more beautiful place. This vision end of April. If you have not received your seed underpins all that we do, from inspirational by 1st May please contact us by email: gardens and shows, through our scientific [email protected] research, to our education and community programmes. We’re committed to inspiring Convention on Biological Diversity everyone to grow. 3Nagoya Protocol4 In accordance with the Convention on Biological Most of the seed offered is collected in RHS Diversity (CBD), the Royal Horticultural Society Gardens. Other seed is donated and is offered supplies seed from its garden collections on the under the name provided by the donor. In many conditions that: cases only limited quantities of seed are available. ⅷ The plant material is used for the common However, we feel that even small quantities good in areas of research, education, should be distributed if at all possible. conservation and the development of horticultural institutions or gardens. Our seed is collected from open-pollinated If the recipient seeks to commercialise the plants, therefore may not come true. ⅷ genetic material, its products or resources derived from it, then written permission must Please note we are only able to send seed to be sought from the Royal Horticultural addresses in the UK and EU6 including Society. -

Koenabib Mine Near Aggeneys, Northern Cape Province

KOENABIB MINE NEAR AGGENEYS, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE BOTANICAL STUDY AND ASSESSMENT Version: 1.0 Date: 30th January 2020 Authors: Gerhard Botha & Dr. Jan -Hendrik Keet PROPOSED MINING OF SILLIMANITE, AGGREGATE AND GRAVEL ON THE FARM KOENABIB 43 NORTH OF AGGENEYS, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Report Title: Botanical Study and Assessment Authors: Mr. Gerhard Botha & Dr. Jan-Hendrik Keet Project Name: Proposed Mining of Sillimanite, Aggregate and Gravel on the Farm Koenabib 43, North of Aggeneys, Northern Cape Province Status of report: Version 1.0 Date: 30th January 2020 Prepared for: Greenmined Environmental Postnet Suite 62, Private Bag X15 Somerset West 7129 Cell: 082 734 5113 Email: [email protected] Prepared by Nkurenkuru Ecology and Biodiversity 3 Jock Meiring Street Park West Bloemfontein 9301 Cell: 083 412 1705 Email: gabotha11@gmail com Suggested report citation Nkurenkuru Ecology and Biodiversity, 2019. Mining Permit, Final Basic Assessment & Environmental Management Plan for the proposed mining of Sillimanite, Aggregate and Stone Gravel on the Farm Koenabib 43, Northern Cape Province. Botanical Study and Assessment Report. Unpublished report prepared by Nkurenkuru Ecology and Biodiversity for GreenMined Environmental. Version 1.0, 30 January 2020. Proposed koenabib sillimanite mine, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE January 2020 botanical STUDY AND ASSESSMENT I. DECLARATION OF CONSULTANTS INDEPENDENCE » act/ed as the independent specialist in this application; » regard the information contained in this report as it relates to my specialist