Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paleolithic and Mesolithic Occupation of the Isle of Jura, Argyll

John MERCER, Edinburgh THE PALAEOLITHIC AND MESOLITHIC OCCUPATION OF THE ISLE OF JURA, ARGYLL, SCOTLAND The occupation sequence about to be described has been built up from a dozen sites concentrated in N-Jura (Mercer, 1968-79).It is based on local land-sea relationships, site stratification, pollen analysis, drifted-pumice dating and radiocarbon assay.The paper 1 will begin with a discussion of the inter-linked shorelines and climate, then give an impression of the main sites and, finally, describe and compare the stone implement typology. Late Glacial habitat 2017 Jura is a vast island (fig.1) some 80 km (50 m) long.It rises to about 780 m (2500ft) Biblioteca, in the south and 470 m (1500 ft)in the north. Several recent papers have shown that W-Scotland was suitable for human habita ULPGC. tion from 11,000 or 10,500 BC. Kirk and Godwin (1963) described an organic level por at Loch Drama (Ross and Cromarty) which, with a C14 date of 12,810 ± 155 be (Q-457), had not since been overlaid by ice, although in a through valley.Kirk com realizada mented: "In view of its location on the exposed, north-west Atlantic rim of Scotland one would except ...an onset of milder oceanic conditions at an earlier date than localities in the English Lowlands or the North European Plain." He concluded his Digitalización contribution: " ... it would appear that in Northern Scotland the process of degla ciation was not unlike that established for Scandinavia, namely an early and rapid autores. los melt of the ice in western fjords and a longer survival in uplands east of the Atlantic watershed.The significance of such a possibility for plant, animal and human coloni sation needs no stressing." documento, Del Coope (summarised in Pennington, 1974), working on beetle remains, noted that © early in Zone I (12,380-10,000 BC) there was a rapid rise in temperature, from less than 10° C as a July average to almost 17° C, though winters may have remained cold. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

Marine ==- Biology © Springer-Verlag 1988

Marine Biology 98, 39-49 (1988) Marine ==- Biology © Springer-Verlag 1988 Analysis of the structure of decapod crustacean assemblages off the Catalan coast (North-West Mediterranean) P. Abell6, F.J. Valladares and A. Castell6n Institute de Ciencias del Mar, Passeig Nacional s/n, E-08003 Barcelona, Spain Abstract Zariquiey Alvarez 1968, Garcia Raso 1981, 1982, 1984), as well as different biological aspects of the economically We sampled the communities of decapod crustaceans important species (Sarda 1980, Sarda etal. 1981, etc.). inhabiting the depth zone between 3 and 871 m off the More recently, some studies of the species distribution of Catalan coast (North-West Mediterranean) from June the decapod crustacean communities of the North-West 1981 to June 1983. The 185 samples comprised 90 species Mediterranean have been published (Sarda and Palo- differing widely in their depth distributions. Multivariate mera 1981, Castellon and Abello 1983, Carbonell 1984, analysis revealed four distinct faunistic assemblages, (1) Abello 1986). However, the quantitative composition of littoral communities over sandy bottoms, (2) shelf com the decapod crustacean communities of this area remain munities over terrigenous muds, (3) upper-slope com largely unknown, and comparable efforts to those of munities, and (4) lower-slope or bathyal communities. The Arena and Li Greci (1973), Relini (1981), or Tunesi (1986) brachyuran crab Liocarcinus depurator is the most abun are lacking. dant species of the shelf assemblage, although L. vernalis The present -

An Ecosystem Model of the North Sea to Support an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management: Description and Parameterisation

Science Series Technical Report no.142 An ecosystem model of the North Sea to support an ecosystem approach to fisheries management: description and parameterisation S. Mackinson and G. Daskalov Science Series Technical Report no.142 An ecosystem model of the North Sea to support an ecosystem approach to fisheries management: description and parameterisation S. Mackinson and G. Daskalov This report should be cited as: Mackinson, S. and Daskalov, G., 2007. An ecosystem model of the North Sea to support an ecosystem approach to fisheries management: description and parameterisation. Sci. Ser. Tech Rep., Cefas Lowestoft, 142: 196pp. This report represents the views and findings of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders. © Crown copyright, 2008 This publication (excluding the logos) may be re-used free of charge in any format or medium for research for non-commercial purposes, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being re-used accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. This publication is also available at www.Cefas.co.uk For any other use of this material please apply for a Click-Use Licence for core material at www.hmso.gov.uk/copyright/licences/ core/core_licence.htm, or by writing to: HMSO’s Licensing Division St Clements House 2–16 Colegate Norwich NR3 1BQ Fax: 01603 723000 E-mail: [email protected] List of contributors and reviewers Name Affiliation -

The Genetic Landscape of Scotland and the Isles

The genetic landscape of Scotland and the Isles Edmund Gilberta,b, Seamus O’Reillyc, Michael Merriganc, Darren McGettiganc, Veronique Vitartd, Peter K. Joshie, David W. Clarke, Harry Campbelle, Caroline Haywardd, Susan M. Ringf,g, Jean Goldingh, Stephanie Goodfellowi, Pau Navarrod, Shona M. Kerrd, Carmen Amadord, Archie Campbellj, Chris S. Haleyd,k, David J. Porteousj, Gianpiero L. Cavalleria,b,1, and James F. Wilsond,e,1,2 aSchool of Pharmacy and Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin D02 YN77, Ireland; bFutureNeuro Research Centre, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin D02 YN77, Ireland; cGenealogical Society of Ireland, Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin A96 AD76, Ireland; dMedical Research Council Human Genetics Unit, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, Scotland; eCentre for Global Health Research, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9AG, Scotland; fBristol Bioresource Laboratories, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, United Kingdom; gMedical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, United Kingdom; hCentre for Academic Child Health, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1NU, United Kingdom; iPrivate address, Isle of Man IM7 2EA, Isle of Man; jCentre for Genomic and Experimental Medicine, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University -

Earthworms at Papadil, Isle of Rum

The Glasgow Naturalist (2016) Volume 26, Part 2, 13-20 An oasis of fertility on a barren island: Earthworms at Papadil, Isle of Rum 1, 4K. R. Butt*, 1C. N. Lowe, 2 M. A. Callaham Jr. and 3V. Nuutinen 1University of Central Lancashire, Preston, PR1 2HE 2 USDA Forest Service, Center for Forest Disturbance Science, Athens, GA, USA 3 Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke) FIN-31600 Jokioinen, Finland 4North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2520 *Email corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT locations, extensive studies have been undertaken, The Isle of Rum, Inner Hebrides, has an for example, across the Outer Hebrides by Boyd impoverished earthworm fauna as the soils are (1957) and more recently on the Isle of Rum in the generally acidic and nutrient-poor. Species Inner Hebrides (Butt & Lowe 2004; Callaham et al associated with human habitation are found around 2012; Gilbert & Butt 2012). Reasons for the interest deserted crofting settlements subjected to in Rum are twofold. Firstly, Rum is a Natural Nature “clearances” in the mid-19th century and at Kinloch, Reserve (NNR) and has been in the management of where a large volume of fertile soil was imported conservation organisations since 1957 (National from the mainland around 1900. Earthworms, and Conservancy (Council) which became Scottish the dew worm Lumbricus terrestris L. in particular, Natural Heritage (SNH)). As a result, considerable were investigated at Papadil, an abandoned scientific research has been undertaken on many settlement and one of the few locations on Rum aspects of the island’s ecology, including soil where a naturally developed brown earth soil is surveys. -

For Review Only 19 20 21 504 Ampuero D, T

Page 1 of 39 Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 1 2 3 1 DNA identification and larval morphology provide new evidence on the systematic 4 5 2 position of Ergasticus clouei A. Milne-Edwards, 1882 (Decapoda, Brachyura, 6 7 3 Majoidea) 8 9 10 4 11 1 2 1 3 12 5 Marco-Herrero, Elena , Torres, Asvin P. , Cuesta, José A. , Guerao, Guillermo , Palero, 13 14 6 Ferran 4, & Abelló, Pere 5 15 16 7 17 18 8 1Instituto de CienciasFor Marinas Review de Andalucía (ICMAN-C OnlySIC), Avda. República 19 20 21 9 Saharaui, 2, 11519 Puerto Real, Cádiz, Spain. 22 2 23 10 Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Centre Oceanogràfic de les Balears, Moll de Ponent 24 25 11 s/n, 07015 Palma, Spain. 26 27 12 3IRTA, Unitat de Cultius Aqüàtics. Ctra. Poble Nou, Km 5.5, 43540 Sant Carles de la 28 29 30 13 Ràpita, Tarragona, Spain. 31 4 32 14 Unitat Mixta Genòmica i Salut CSISP-UV, Institut Cavanilles Universitat de Valencia, 33 34 15 C/ Catedrático José Beltrán 2, 46980 Paterna, Spain. 35 36 16 5Institut de Ciències del Mar (CSIC), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta 37-49, 08003 37 38 17 Barcelona, Catalonia. Spain. 39 40 41 18 42 43 19 44 45 20 46 47 21 RUN TITLE: Larval evidence and the systematic position of Ergasticus clouei 48 49 50 22 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society Page 2 of 39 1 2 3 23 ABSTRACT: The morphology of the complete larval stage series of the crab Ergasticus 4 5 24 clouei is described and illustrated based on larvae (zoea I, zoea II and megalopa) 6 7 25 captured from plankton samples taken in Mediterranean waters. -

A Composer's Ear-Lead Approach to Exploring Island Culture Past And

Title Listening for the past: A composer's ear-lead approach to exploring island culture past and present in the Outer Hebrides Type Article URL http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/11495/ Date 2011 Citation Lane, Cathy (2011) Listening for the past: A composer's ear-lead approach to exploring island culture past and present in the Outer Hebrides. Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures, 5 (1). pp. 32- 39. ISSN 1834-6057 Creators Lane, Cathy Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Lane – Outer Hebrides LISTENING FOR THE PAST A composer's ear-lead approach to exploring island culture past and present in the Outer Hebrides CATHY LANE University of the Arts, London <[email protected]> Abstract The landscapes of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland are littered with the visual remnants of a turbulent past but can past events be said to leave sonic as well as visual traces? This article discusses three aspects of a practice-based research project. The first is the author's exploration of these islands and their history through sound in order to try to find elusive sonic traces of the past. The second concerns the issues and problems of finding and recording sound in the Outer Hebrides. The third is the artistic challenge of communicating something about history and memory, related to the Outer Hebrides, through the medium of composed sound using a mixture of monologues, field recordings and interviews collected during a number of trips to the islands as well as material from oral history archives. -

Download Trip Notes

Isle of Skye and The Small Isles - Scotland Trip Notes TRIP OVERVIEW Take part in a truly breathtaking expedition through some of the most stunning scenery in the British Isles; Scotland’s world-renowned Inner Hebrides. Basing ourselves around the Isles of Skye, Rum, Eigg and Muck and staying on board the 102-foot tall ship, the ‘Lady of Avenel’, this swimming adventure offers a unique opportunity to explore the dramatic landscapes of this picturesque corner of the world. From craggy mountain tops to spectacular volcanic features, this tour takes some of the most beautiful parts of this collection of islands, including the spectacular Cuillin Hills. Our trip sees us exploring the lochs, sounds, islands, coves and skerries of the Inner Hebrides, while also providing an opportunity to experience an abundance of local wildlife. This trip allows us to get to know the islands of the Inner Hebrides intimately, swimming in stunning lochs and enjoying wild coastal swims. We’ll journey to the islands on a more sustainable form of transport and enjoy freshly cooked meals in our downtime from our own onboard chef. From sunsets on the ships deck, to even trying your hand at crewing the Lady of Avenel, this truly is an epic expedition and an exciting opportunity for adventure swimming and sailing alike. WHO IS THIS TRIP FOR? This trip is made up largely of coastal, freshwater loch swimming, along with some crossings, including the crossing from Canna to Rum. Conditions will be challenging, yet extremely rewarding. Swimmers should have a sound understanding and experience of swimming in strong sea conditions and be capable of completing the average daily swim distance of around 4 km (split over a minimum of two swims) prior to the start of the trip. -

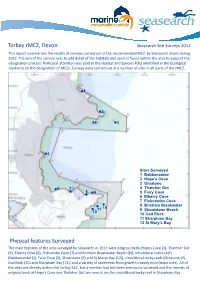

Torbay Rmcz, Devon Physical Features Surveyed

Torbay rMCZ, Devon Seasearch Site Surveys 2012 This report summarises the results of surveys carried out in the recommended MCZ by Seasearch divers during 2012. The aim of the surveys was to add detail of the habitats and species found within the area to support the designation process. Particular attention was paid to the Habitat and Species FOCI identified in the Ecological Guidance on the designation of MCZs. Surveys were carried out at a number of sites in all parts of the rMCZ. 1 2 4 3 5 Sites Surveyed 1 Babbacombe 2 Hope’s Cove CW 3 Orestone 6 7 4 Thatcher Gut 8 9 5 Fairy Cove 6 Elberry Cove 7 Fishcombe Cove 8 Brixham Breakwater 10 11 9 Shoalstone Beach 12 10 Cod Rock 11 Sharpham Bay 12 St Mary’s Bay Physical features Surveyed The main features of the area surveyed by Seasearch in 2012 were eelgrass beds (Hopes Cove (2), Thatcher Gut (4), Elberry Cove (6), Fishcombe Cove (7) and Brixham Breakwater Beach (8)), infralittoral rocky reefs (Babbacombe (1), Fairy Cove (5), Shoalstone (9) and St Marys Bay (12)), circalittoral rocky reefs (Orestone (3), Cod Rock (10) and Sharpham Bay (11)) and a variety of sediments from gravel to sandy mud (most sites). All of the sites are already within the Torbay SAC, but a number had not been previously surveyed and the records of eelgrass beds at Hope’s Cove and Thatcher Gut are new, is arCWe the circalittoral rocky reef in Sharpham Bay. CW Features of the Marine Life and Habitats Eeelgrass Beds (Sites 2,4,6,7,8) Eelgrass, Zostera marina, is one of the very few flowering plants underwater and, unlike seaweeds, has a system of roots which can help to bind soft sediments and create a complex habitat in what would otherwise be a relatively un-diverse environment. -

Decapoda, Brachyura

APLICACIÓN DE TÉCNICAS MORFOLÓGICAS Y MOLECULARES EN LA IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LA MEGALOPA de Decápodos Braquiuros de la Península Ibérica bérica I enínsula P raquiuros de la raquiuros B ecápodos D de APLICACIÓN DE TÉCNICAS MORFOLÓGICAS Y MOLECULARES EN LA IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LA MEGALOPA LA DE IDENTIFICACIÓN EN LA Y MOLECULARES MORFOLÓGICAS TÉCNICAS DE APLICACIÓN Herrero - MEGALOPA “big eyes” Leach 1793 Elena Marco Elena Marco-Herrero Programa de Doctorado en Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva Rd. 99/2011 Tesis Doctoral, Valencia 2015 Programa de Doctorado en Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva Rd. 99/2011 APLICACIÓN DE TÉCNICAS MORFOLÓGICAS Y MOLECULARES EN LA IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LA MEGALOPA DE DECÁPODOS BRAQUIUROS DE LA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA TESIS DOCTORAL Elena Marco-Herrero Valencia, septiembre 2015 Directores José Antonio Cuesta Mariscal / Ferran Palero Pastor Tutor Álvaro Peña Cantero Als naninets AGRADECIMIENTOS-AGRAÏMENTS Colaboración y ayuda prestada por diferentes instituciones: - Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (actual Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad) por la concesión de una Beca de Formación de Personal Investigador FPI (BES-2010- 033297) en el marco del proyecto: Aplicación de técnicas morfológicas y moleculares en la identificación de estados larvarios planctónicos de decápodos braquiuros ibéricos (CGL2009-11225) - Departamento de Ecología y Gestión Costera del Instituto de Ciencias Marinas de Andalucía (ICMAN-CSIC) - Club Náutico del Puerto de Santa María - Centro Andaluz de Ciencias y Tecnologías Marinas (CACYTMAR) - Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO), Centros de Mallorca y Cádiz - Institut de Ciències del Mar (ICM-CSIC) de Barcelona - Institut de Recerca i Tecnología Agroalimentàries (IRTA) de Tarragona - Centre d’Estudis Avançats de Blanes (CEAB) de Girona - Universidad de Málaga - Natural History Museum of London - Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn di Napoli (SZN) - Universitat de Barcelona AGRAÏSC – AGRADEZCO En primer lugar quisiera agradecer a mis directores, el Dr.