Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors Versus Placebo in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Efficacy of Treatments for Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: a Systematic Review

REVIEW Efficacy of treatments for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review Yun-Jung Choi, PhD, RN, PMHNP (Lecturer) Keywords Abstract Systematic review; obsessive-compulsive disorder; efficacy of medication. Purpose: This systematic review examines the efficacy of pharmacological therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), addressing two major issues: Correspondence which treatment is most effective in treating the patient’s symptoms and which Yun-Jung Choi, PhD, RN, PMHNP, Red Cross is beneficial for maintaining remission. College of Nursing, 98 Saemoonan-Gil, Data sources: Seven databases were used to acquire articles. The key words Jongno-Gu, Seoul 110-102, Korea; used to search for the relative topics published from 1996 to 2007 were Tel: +82-2-3700-3676; fax: +82-2-3700-3400; ‘‘obsessive-compulsive disorder’’ and ‘‘Yale-Brown obsession-compulsion E-mail: [email protected] scale.’’ Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 25 studies were selected Received: August 2007; from 57 potentially relevant studies. accepted: March 2008 Conclusions: The effects of treatment with clomipramine and selective sero- tonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs: fluvoxamine, sertraline, fluoxetine, citalo- doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00408.x pram, and escitalopram) proved to be similar, except for the lower adherence rate in case of clomipramine because of its side effects. An adequate drug trial involves administering an effective daily dose for a minimum of 8 weeks. An augmentation strategy proven effective for individuals refractory to monother- apy with SSRI treatment alone is the use of atypical antipsychotics (risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine). Implications for practice: Administration of fluvoxamine or sertraline to patients for an adequate duration is recommended as the first-line prescription for OCD, and augmentation therapy with risperidone, olanzapine, or quetiapine is recommended for refractory OCD. -

Antinociceptive Effects of Monoamine Reuptake Inhibitors in Assays of Pain-Stimulated and Pain-Depressed Behaviors

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Antinociceptive Effects of Monoamine Reuptake Inhibitors in Assays of Pain-Stimulated and Pain-Depressed Behaviors Marisa Rosenberg Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Medical Pharmacology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2715 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANTINOCICEPTIVE EFFECTS OF MONOAMINE REUPTAKE INHIBITORS IN ASSAYS OF PAIN-STIMULATED AND PAIN-DEPRESSED BEHAVIOR A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at Virginia Commonwealth University By Marisa B. Rosenberg Bachelor of Science, Temple University, 2008 Advisor: Sidney Stevens Negus, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Pharmacology/Toxicology Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, VA May, 2012 Acknowledgement First and foremost, I’d like to thank my advisor Dr. Steven Negus, whose unwavering support, guidance and patience throughout my graduate career has helped me become the scientist I am today. His dedication to education, learning and the scientific process has instilled in me a quest for knowledge that I will continue to pursue in life. His thoroughness, attention to detail and understanding of pharmacology has been exemplary to a young person like me just starting out in the field of science. I’d also like to thank all of my committee members (Drs. -

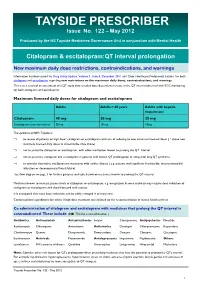

TAYSIDE PRESCRIBER Issue No

TAYSIDE PRESCRIBER Issue No. 122 – May 2012 Produced by the NS Tayside Medicines Governance Unit in conjunction with Mental Health Citalopram & escitalopram:QT interval prolongation New maximum daily dose restrictions, contraindications, and warnings Information has been issued via Drug Safety Update, Volume 5, Issue 5, December 2011 and ‘Dear Healthcare Professional Letters’ for both citalopram and escitalopram regarding new restrictions on the maximum daily doses, contraindications, and warnings. This is as a result of an assessment of a QT study that revealed dose-dependent increase in the QT interval observed with ECG monitoring for both citalopram and escitalopram. Maximum licensed daily doses for citalopram and escitalopram Adults Adults > 65 years Adults with hepatic impairment Citalopram 40 mg 20 mg 20 mg Escitalopram (non-formulary) 20 mg 10 mg 10mg The guidance in NHS Tayside is: ⇒ to review all patients on high dose* citalopram or escitalopram with aim of reducing to new maximum licensed doses ( * above new maximum licensed daily doses as stated in the table above) ⇒ not to prescribe citalopram or escitalopram with other medication known to prolong the QT interval ⇒ not to prescribe citalopram and escitalopram in patients with known QT prolongation or congenital long QT syndrome ⇒ to consider alternative antidepressant in patients with cardiac disease ( e.g. patients with significant bradycardia; recent myocardial infarction or decompensated heart failure) See flow diagram on page 3 for further guidance and table below on medicines known to prolong the QT interval. Medicines known to increase plasma levels of citalopram or escitalopram, e.g. omeprazole & some antivirals may require dose reduction of citalopram or escitalopram and should be used with caution. -

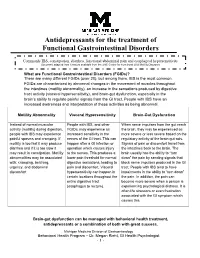

Antidepressants for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

Antidepressants for the treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Commonly IBS, constipation, diarrhea, functional abdominal pain and esophageal hypersensitivity Document adapted from literature available from the UNC Center for Functional GI & Motility Disorders What are Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDs)? There are many different FGIDs (over 20), but among them, IBS is the most common. FGIDs are characterized by abnormal changes in the movement of muscles throughout the intestines (motility abnormality), an increase in the sensations produced by digestive tract activity (visceral hypersensitivity), and brain-gut dysfunction, especially in the brain’s ability to regulate painful signals from the GI tract. People with IBS have an increased awareness and interpretation of these activities as being abnormal. Motility Abnormality Visceral Hypersensitivity Brain-Gut Dysfunction Instead of normal muscular People with IBS, and other When nerve impulses from the gut reach activity (motility) during digestion, FGIDs, may experience an the brain, they may be experienced as people with IBS may experience increased sensitivity in the more severe or less severe based on the painful spasms and cramping. If nerves of the GI tract. This can regulatory activity of the brain-gut axis. motility is too fast it may produce happen after a GI infection or Signals of pain or discomfort travel from diarrhea and if it is too slow it operation which causes injury the intestines back to the brain. The may result in constipation. Motility to the nerves. This produces a brain usually has the ability to “turn abnormalities may be associated lower pain threshold for normal down” the pain by sending signals that with: cramping, belching, digestive sensations, leading to block nerve impulses produced in the GI urgency, and abdominal pain and discomfort. -

Adverse Effects of First-Line Pharmacologic Treatments of Major Depression in Older Adults

Draft Comparative Effectiveness Review Number xx Adverse Effects of First-line Pharmacologic Treatments of Major Depression in Older Adults Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov This information is distributed solely for the purposes of predissemination peer review. It has not been formally disseminated by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The findings are subject to change based on the literature identified in the interim and peer-review/public comments and should not be referenced as definitive. It does not represent and should not be construed to represent an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or Department of Health and Human Services (AHRQ) determination or policy. Contract No. 290-2015-00012I Prepared by: Will be included in the final report Investigators: Will be included in the final report AHRQ Publication No. xx-EHCxxx <Month, Year> ii Purpose of the Review To assess adverse events of first-line antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults 65 years or older. Key Messages • Acute treatment (<12 weeks) with o Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (duloxetine, venlafaxine), but not selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (escitalopram, fluoxetine) led to a greater number of adverse events compared with placebo. o SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram and fluoxetine) and SNRIs (duloxetine and venlafaxine) led to a greater number of patients withdrawing from studies due to adverse events compared with placebo o Details of the contributing adverse events in RCTs were rarely reported to more clearly characterize what adverse events to expect. -

Acute Inhibitory Effects of Antidepressants on Lacrimal Gland Secretion in the Anesthetized Rat

Physiology and Pharmacology Acute Inhibitory Effects of Antidepressants on Lacrimal Gland Secretion in the Anesthetized Rat Martin Dankis, Ozgu Aydogdu, Gunnar Tobin, and Michael Winder Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, the Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Correspondence: Michael Winder, PURPOSE. Patients that medicate with antidepressants commonly report dryness of eyes. Department of Pharmacology, The cause is often attributed to the anticholinergic properties of the drugs. However, regu- Institute of Neuroscience and lation of tear production includes a substantial reflex-evoked component and is regulated Physiology, the Sahlgrenska via distinct centers in the brain. Further, the anticholinergic component varies greatly Academy, University of Gothenburg, among antidepressants with different mechanisms of action. In the current study it was Medicinaregatan 13 413 90, Gothenburg, Sweden; wondered if acute administration of antidepressants can disturb production of tears by [email protected]. affecting the afferent and/or central pathway. Received: November 9, 2020 METHODS. Tear production was examined in vivo in anesthetized rats in the presence Accepted: May 10, 2021 or absence of the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) clomipramine or the selective sero- Published: June 7, 2021 tonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) escitalopram. The reflex-evoked production of tears was Citation: Dankis M, Aydogdu O, measured by challenging the surface of the eye with menthol (0.1 mM) and choliner- Tobin G, Winder M. Acute inhibitory gic regulation was examined by intravenous injection with the nonselective muscarinic effects of antidepressants on agonist methacholine (1–5 μg/kg). lacrimal gland secretion in the RESULTS. Acute administration of clomipramine significantly attenuated both reflex- anesthetized rat. -

Prescribing Guidance for Citalopram and Escitalopram Hull and East Riding Prescribing Committee

Prescribing Guidance for Citalopram and Escitalopram Hull and East Riding Prescribing Committee Summary of Safety Alert (December 2011) – http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/DrugSafetyUpdate/CON137769 Citalopram and escitalopram are associated with dose-dependent QT interval prolongation and should not be used in those with: congenital long QT syndrome; known pre-existing QT interval prolongation; or in combination with other medicines that prolong the QT interval. ECG measurements should be considered for patients with cardiac disease, and electrolyte disturbances should be corrected before starting treatment. For citalopram, new restrictions on the maximum daily doses now apply: 40 mg for adults; 20 mg for patients older than 65 years; and 20 mg for those with hepatic impairment. For escitalopram, the maximum daily dose for patients older than 65 years is now reduced to 10 mg/day; other doses remain unchanged. Recommended actions for prescribers If dose is above maximum recommended dose or patient is taking other medications likely to prolong QTc: Need for more than 1. Discuss with service user/patient. citalopram 40mg daily 2. Consider continued need for citalopram and/or alternative therapies (adults), 20mg daily (elderly and reduced hepatic function) e.g. for OCD, PTSD Adult citalopram Elderly (or other risk factors) Taking ANY other medicines Elderly and escitalopram dose above citalopram dose above likely to cause QTc dose above 10mg daily: prolongation 40mg daily: 20mg daily: Consider risk/benefit with service user. Switch if 1-Consider switching relevant possible medication to alternative with no Monitor If under 18 refer to CAMHS effect on QTc prolongation or Reduce dose stepwise to 40mg citalopram daily for adults (unlicensed use). -

Medication Guide Escitalopram Tablets (ES-Sye-TAL-Oh-Pram)

Medication Guide Escitalopram Tablets (ES-sye-TAL-oh-pram) Read the Medication Guide that comes with escitalopram tablets before you start taking it and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This Medication Guide does not take the place of talking to your healthcare provider about your medical condition or treatment. Talk with your healthcare provider if there is something you do not understand or want to learn more about. What is the most important information I should know about escitalopram tablets? Escitalopram tablets and other antidepressant medicines may cause serious side effects, including: 1. Suicidal thoughts or actions: • Escitalopram tablets and other antidepressant medicines may increase suicidal thoughts or actions in some children, teenagers, or young adults within the first few months of treatment or when the dose is changed. • Depression or other serious mental illnesses are the most important causes of suicidal thoughts or actions. • Watch for these changes and call your healthcare provider right away if you notice: • New or sudden changes in mood, behavior, actions, thoughts, or feelings, especially if severe. • Pay particular attention to such changes when escitalopram tablet is started or when the dose is changed. Keep all follow-up visits with your healthcare provider and call between visits if you are worried about symptoms. Call your healthcare provider right away if you have any of the following symptoms, or call 911 if an emergency, especially if they are new, worse, or worry you: • attempts to commit suicide • acting on dangerous impulses • acting aggressive or violent • thoughts about suicide or dying • new or worse depression • new or worse anxiety or panic attacks • feeling agitated, restless, angry or irritable • trouble sleeping • an increase in activity or talking more than what is normal for you • other unusual changes in behavior or mood 38 Call your healthcare provider right away if you have any of the following symptoms, or call 911 if an emergency. -

Review Article Monoamine Reuptake Inhibitors in Parkinson's Disease

Review Article Monoamine Reuptake Inhibitors in Parkinson’s Disease Philippe Huot,1,2,3 Susan H. Fox,1,2 and Jonathan M. Brotchie1 1 Toronto Western Research Institute, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, 399 Bathurst Street, Toronto, ON, Canada M5T 2S8 2Division of Neurology, Movement Disorder Clinic, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, University of Toronto, 399BathurstStreet,Toronto,ON,CanadaM5T2S8 3Department of Pharmacology and Division of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, UniversitedeMontr´ eal´ and Centre Hospitalier de l’UniversitedeMontr´ eal,´ Montreal,´ QC, Canada Correspondence should be addressed to Jonathan M. Brotchie; [email protected] Received 19 September 2014; Accepted 26 December 2014 Academic Editor: Maral M. Mouradian Copyright © 2015 Philippe Huot et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The motor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease (PD) are secondary to a dopamine deficiency in the striatum. However, the degenerative process in PD is not limited to the dopaminergic system and also affects serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons. Because they can increase monoamine levels throughout the brain, monoamine reuptake inhibitors (MAUIs) represent potential therapeutic agents in PD. However, they are seldom used in clinical practice other than as antidepressants and wake-promoting agents. This review -

Citalopram/Escitalopram (Celexa/Lexapro

Citalopram | Escitalopram (Celexa® | Lexapro®) This sheet is about using citalopram/escitalopram in a pregnancy and while breastfeeding. This information should not take the place of medical care and advice from your healthcare provider. What is citalopram and escitalopram? Citalopram is a medication used to treat depression. Citalopram belongs to the class of antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). A common brand name for citalopram is Celexa®. The drug escitalopram contains the same active medication as citalopram. These two drugs act in the body in a very similar way. Escitalopram is used to treat depression and generalized anxiety disorder. It is also an SSRI and is sold under the brand name Lexapro®. Sometimes when people find out they are pregnant, they think about changing how they take their medication, or stopping their medication altogether. However, it is important to talk with your healthcare providers before making any changes to how you take this medication. Your healthcare providers can talk with you about the benefits of treating your condition and the risks of untreated illness during pregnancy. Should you choose to stop taking this medication, it is important to have other forms of support in place (e.g. counseling or therapy) and a plan to restart the medication after delivery, if needed. I take citalopram/escitalopram. Can it make it harder for me to get pregnant? It is not known if citalopram/escitalopram can make it harder to get pregnant. Studies in animals found that citalopram might cause some reduced fertility (ability to get pregnant). Does taking citalopram/escitalopram increase the chance for miscarriage? Miscarriage can occur in any pregnancy. -

Lexapro (Escitalopram Oxalate) Tablets/Oral Solution NDA 21-323/NDA 21-365 Proposed Labeling Text

Lexapro (escitalopram oxalate) Tablets/Oral Solution NDA 21-323/NDA 21-365 Proposed Labeling Text Lexapro® (escitalopram oxalate) TABLETS/ORAL SOLUTION Rx Only Suicidality and Antidepressant Drugs Antidepressants increased the risk compared to placebo of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term studies of major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Anyone considering the use of Lexapro or any other antidepressant in a child, adolescent, or young adult must balance this risk with the clinical need. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction in risk with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older. Depression and certain other psychiatric disorders are themselves associated with increases in the risk of suicide. Patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber. Lexapro is not approved for use in pediatric patients. (See WARNINGS: Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk, PRECAUTIONS: Information for Patients, and PRECAUTIONS: Pediatric Use) DESCRIPTION Lexapro® (escitalopram oxalate) is an orally administered selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Escitalopram is the pure S-enantiomer (single isomer) of the racemic bicyclic phthalane derivative citalopram. Escitalopram oxalate is designated S-(+)-1-[3-(dimethyl-amino)propyl]-1-(p fluorophenyl)-5-phthalancarbonitrile oxalate with the following structural formula: •C2H2O4 The molecular formula is C20H21FN2O • C2H2O4 and the molecular weight is 414.40. -

Providers | Medications for Depression

Medications for Depression Antidepressants alter the concentrations of one or more key neurotransmitters in the brain, namely norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine. As depression may be a presenting symptom of a mixed manic episode, it is important to adequately screen patients with depressive symptoms to determine if they are at risk of bipolar disorder. All patients should also be monitored with regards to mental status for depression, suicidal ideation, anxiety, social functioning, mania, panic attacks, or other unusual changes in behavior. All antidepressants carry a black box warning of increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children and adolescents, particularly in the first few months of therapy. MAOIs are contraindicated with all other classes of antidepressants and should not be used in combination. Common side effects often improve within the first two weeks of treatment. A low starting dose might help increase tolerance and adherence. DRUG CATEGORY MEDICATION COMMON SIDE EFFECTS MONITORING PARAMETERS ADDITIONAL COMMENTS Selective Serotonin .Citalopram (IR, Liq)* .GI: effects are common (nausea, xerostomia, diarrhea) .Weight and BMI .Comparable to TCAs in efficacy, but are markedly safer and better tolerated Reuptake Inhibitors .Escitalopram (IR, Liq) .Sexual dysfunction: in both men & women .Signs/symptoms of serotonin syndrome .SSRIs differ from each other with respect to their degree of selectivity for the serotonin (SSRIs) .Fluoxetine (IR, Liq ) .Hematologic: Impaired platelet aggregation/bleeding .Electrolytes,