Current and Experimental Therapeutics of Ocd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pindolol of the Activation of Postsynaptic 5-HT1A Receptors

Potentiation by (-)Pindolol of the Activation of Postsynaptic 5-HT1A Receptors Induced by Venlafaxine Jean-Claude Béïque, Ph.D., Pierre Blier, M.D., Ph.D., Claude de Montigny, M.D., Ph.D., and Guy Debonnel, M.D. The increase of extracellular 5-HT in brain terminal regions antagonist WAY 100635 (100 g/kg, i.v.). A short-term produced by the acute administration of 5-HT reuptake treatment with VLX (20 mg/kg/day ϫ 2 days) resulted in a inhibitors (SSRI’s) is hampered by the activation of ca. 90% suppression of the firing activity of 5-HT neurons somatodendritic 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the raphe nuclei. in the dorsal raphe nucleus. This was prevented by the The present in vivo electrophysiological studies were coadministration of (-)pindolol (15 mg/kg/day ϫ 2 days). undertaken, in the rat, to assess the effects of the Taken together, these results indicate that (-)pindolol coadministration of venlafaxine, a dual 5-HT/NE reuptake potentiated the activation of postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors inhibitor, and (-)pindolol on pre- and postsynaptic 5-HT1A resulting from 5-HT reuptake inhibition probably by receptor function. The acute administration of venlafaxine blocking the somatodendritic 5-HT1A autoreceptor, but not and of the SSRI paroxetine (5 mg/kg, i.v.) induced a its postsynaptic congener. These results support and extend suppression of the firing activity of dorsal hippocampus CA3 previous findings providing a biological substratum for the pyramidal neurons. This effect of venlafaxine was markedly efficacy of pindolol as an accelerating strategy in major potentiated by a pretreatment with (-)pindolol (15 mg/kg, depression. -

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. [Revised.) INSTITUTION National Inst

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 408 729 EC 305 600 AUTHOR Strock, Margaret TITLE Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. [Revised.) INSTITUTION National Inst. of Mental Health (DHHS), Rockville, Md. REPORT NO NIH-pub-96-3755 PUB DATE Sep96 NOTE 24p. AVAILABLE FROM National Institute of Mental Health, Information Resources and Inquiries Branch, 5600 Fishers Lane, Room 7C-02, Rockville, MD 20857. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Behavior Disorders; *Behavior Modification; *Disability Identification; *Drug Therapy; Incidence; Intervention; Mental Disorders; *Neurological Impairments; Outcomes of Treatment; *Symptoms (Individual Disorders) IDENTIFIERS *Obsessive Compulsive Behavior ABSTRACT This booklet provides an overview of the causes, symptoms, and incidence of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and addresses the key features of OCD, including obsessions, compulsions, realizations of senselessness, resistance, and shame and secrecy. Research findings into the causes of OCD are reviewed which indicate that the brains of individuals with OCD have different patterns of brain activity than those of people without mental illness or with some other mental illness. Other types of illness that may be linked to OCD are noted, such as Tourette syndrome, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder and hypochondriasis. The use of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy to treat individuals with OCD is evaluated and a screening test for OCD is presented, along with information on how to get help for OCD. Lists of organizations that can be contacted and related books on the subject are also provided. Case histories of people with OCD are included in the margins of the booklet. (Contains 11 references.) (CR) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Schizophrenia Care Guide

August 2015 CCHCS/DHCS Care Guide: Schizophrenia SUMMARY DECISION SUPPORT PATIENT EDUCATION/SELF MANAGEMENT GOALS ALERTS Minimize frequency and severity of psychotic episodes Suicidal ideation or gestures Encourage medication adherence Abnormal movements Manage medication side effects Delusions Monitor as clinically appropriate Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Danger to self or others DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA/EVALUATION (PER DSM V) 1. Rule out delirium or other medical illnesses mimicking schizophrenia (see page 5), medications or drugs of abuse causing psychosis (see page 6), other mental illness causes of psychosis, e.g., Bipolar Mania or Depression, Major Depression, PTSD, borderline personality disorder (see page 4). Ideas in patients (even odd ideas) that we disagree with can be learned and are therefore not necessarily signs of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a world-wide phenomenon that can occur in cultures with widely differing ideas. 2. Diagnosis is made based on the following: (Criteria A and B must be met) A. Two of the following symptoms/signs must be present over much of at least one month (unless treated), with a significant impact on social or occupational functioning, over at least a 6-month period of time: Delusions, Hallucinations, Disorganized Speech, Negative symptoms (social withdrawal, poverty of thought, etc.), severely disorganized or catatonic behavior. B. At least one of the symptoms/signs should be Delusions, Hallucinations, or Disorganized Speech. TREATMENT OPTIONS MEDICATIONS Informed consent for psychotropic -

(Orion) 5 Mg Tablets Buspirone (Orion) 10 Mg Tablets

NEW ZEALAND DATA SHEET 1. PRODUCT NAME Buspirone (Orion) 5 mg tablets Buspirone (Orion) 10 mg tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each tablet contains 5 mg buspirone hydrochloride. Each tablet contains 10 mg buspirone hydrochloride. Excipient with known effect: 5 mg tablet: Each tablet contains 59.5 mg lactose (as monohydrate) 10 mg tablet: Each tablet contains 118.9 mg lactose (as monohydrate). For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Tablet. 5 mg tablet: White or almost white, oval tablets debossed with ‘ORN 30’ on one side and a score on the other side. The tablet can be divided into equal doses. 10 mg tablet: White or almost white, oval tablets debossed with ‘ORN 31’ on one side and a score on the other side. The tablet can be divided into equal doses. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Buspirone hydrochloride is indicated for the management of anxiety with or without accompanying depression in adults. Buspirone hydrochloride is indicated for the management of anxiety disorders or the short- term relief of symptoms of anxiety with or without accompanying depression. 4.2 Posology and method of administration The usual starting dose is 5 mg given three times daily. This may be titrated according to the needs of the patient and the daily dose increased by 5 mg increments every two or three days depending upon the therapeutic response to a maximum daily dose of 60 mg. After dosage titration the usual daily dose will be 20 to 30 mg per day in divided doses. -

MODERN INDICATIONS for the USE of OPIPRAMOL Krzysztof Krysta1, Sławomir Murawiec2, Anna Warchala1, Karolina Zawada3, Wiesław J

Psychiatria Danubina, 2015; Vol. 27, Suppl. 1, pp 435–437 Conference paper © Medicinska naklada - Zagreb, Croatia MODERN INDICATIONS FOR THE USE OF OPIPRAMOL Krzysztof Krysta1, Sławomir Murawiec2, Anna Warchala1, Karolina Zawada3, Wiesław J. Cubała4, Mariusz S. Wiglusz4, Katarzyna Jakuszkowiak-Wojten4, Marek Krzystanek5 & Irena Krupka-Matuszczyk1 1Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland 2“Dialogue” Therapy Centre, Warsaw, Poland 3Department of Pneumonology, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland 4Department of Psychiatry, Medical University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland 5Department of Rehabilitation Psychiatry, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland SUMMARY Opipramol is considered as a pharmacological agent that does not fit the classification taking into account the division of antidepressants, antipsychotics and anxiolytics. It has a structure related to tricyclic antidepressants but it has a different mechanism of action, i.e. binding to sigma1 and to sigma2 sites. It has been regarded as an effective drug in general anxiety disorders together with other agents like SSRI`s, SNRI`s, buspirone and pregabalin for many years. It can however also be indicated in other conditions, e.g. it may be used as a premedication in the evening prior to surgery, positive results are also observed in psychopharmacological treatment with opipramol in somatoform disorders, symptoms of depression can be significantly reduced in the climacteric syndrome. The latest data from literature present also certain dangers and side effects, which may result due to opipramol administration. Mania may be induced not only in bipolar patients treated with opipramol, but it can be an adverse drug reaction in generalized anxiety disorder. This analysis shows however that opipramol is an important drug still very useful in different clinical conditions. -

200750261.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Compulsivity in obsessive-compulsive disorder and addictions Martijn Figeea, Tommy Pattijb, Ingo Willuhna,c, Judy Luigjesa, Wim van den Brinka,d, Anneke Goudriaana,d, Marc N. Potenzae, Trevor W. Robbinsf, Damiaan Denysa,c a Academic Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Amsterdam, the Netherlands b Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam, Department of Anatomy and Neurosciences, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. c The Institute for Neuroscience, an institute of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Amsterdam, The Netherlands d Amsterdam Institute for Addiction Research, Amsterdam, the Netherlands e Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States; Department of Neurobiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States; Child Study Center, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States. f Department of Psychology and Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom Please address all correspondence to: Damiaan Denys, M.D., Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Department of Psychiatry, Postbox 75867, 1070 AW Amsterdam, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Compulsive behaviors are driven by repetitive urges and typically involve the experience of limited voluntary control over these urges, a diminished ability to delay or inhibit these behaviors, and a tendency to perform repetitive acts in a habitual or stereotyped manner. Compulsivity is not only a central characteristic of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) but is also crucial to addiction. Based on this analogy, OCD has been proposed to be part of the concept of behavioral addiction along with other non-drug-related disorders that share compulsivity, such as pathological gambling, skin-picking, trichotillomania and compulsive eating. -

Does Curcumin Or Pindolol Potentiate Fluoxetine's Antidepressant Effect

Research Paper Does Curcumin or Pindolol Potentiate Fluoxetine’s Antidepressant Effect by a Pharmacokinetic or Pharmacodynamic Interaction? H. A. S. MURAD*, M. I. SULIAMAN1, H. ABDALLAH2 AND MAY ABDULSATTAR1 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Rabigh, King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah-21589, Saudi Arabia (SA) and Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo-11541, Egypt. 1Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, KAU, Jeddah-21589, SA. 2Department of Natural Products, Faculty of Pharmacy, KAU, Jeddah-21589, SA and Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, Cairo-11541, Egypt Murad, et al.: Potentiation of Fluoxetine by Curcumin This study was designed to study potentiation of fluoxetine’s antidepressant effect by curcumin or pindolol. Twenty eight groups of mice (n=8) were used in three sets of experiments. In the first set, 9 groups were subjected to the forced swimming test after being treated intraperitoneally with three vehicles, fluoxetine (5 and 20 mg/kg), curcumin (20 mg/kg), pindolol (32 mg/kg), curcumin+fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) and pindolol+fluoxetine (5 mg/kg). One hour after the test, serum and brain fluoxetine and norfluoxetine levels were measured in mice receiving fluoxetine (5 and 20 mg/kg), curcumin+fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) and pindolol+fluoxetine (5 mg/kg). In the second set, the test was done after pretreatment with p-chlorophenylalanine. In the third set, the locomotor activity was measured. The immobility duration was significantly decreased in fluoxetine (20 mg/kg), curcumin (20 mg/kg), curcumin+fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) and pindolol+fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) groups. These decreases were reversed with p-chlorophenylalanine. -

Serotonin and Drug-Induced Therapeutic Responses in Major Depression, Obsessive–Compulsive and Panic Disorders Pierre Blier, M.D., Ph.D

Serotonin and Drug-Induced Therapeutic Responses in Major Depression, Obsessive–Compulsive and Panic Disorders Pierre Blier, M.D., Ph.D. and Claude de Montigny, M.D., Ph.D. The therapeutic effectiveness of antidepressant drugs in major development of treatment strategies producing greater efficacy depression was discovered by pure serendipity. It took over 20 and more rapid onset of antidepressant action; that, is lithium years before the neurobiological modifications that could addition and pindolol combination, respectively. It is expected mediate the antidepressive response were put into evidence. that the better understanding recently obtained of the Indeed, whereas the immediate biochemical effects of these mechanism of action of certain antidepressant drugs in drugs had been well documented, their antidepressant action obsessive– compulsive and panic disorders will also lead to generally does not become apparent before 2 to 3 weeks of more effective treatment strategies for those disorders. treatment. The different classes of antidepressant [Neuropsychopharmacology 21:91S–98S, 1999] treatments were subsequently shown to enhance serotonin © 1999 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. neurotransmission albeit via different pre- and postsynaptic Published by Elsevier Science Inc. mechanisms. Clinical trials based on this hypothesis led to the KEY WORDS: Antidepressant; Electroconvulsive shocks; electroconvulsive shock treatment (ECT), which was Lithium; Pindolol; Hippocampus; Orbito-frontal cortex generally given only to hospitalized patients. It took several years after the demonstration of the In the late 1950s, the therapeutic effect of certain drugs antidepressant effect of iproniazide and imipramine to in major depression was discovered by serendipity. An understand that these drugs could interfere with the ca- antidepressant response was observed in patients with tabolism of monoamines. -

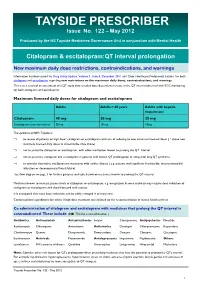

TAYSIDE PRESCRIBER Issue No

TAYSIDE PRESCRIBER Issue No. 122 – May 2012 Produced by the NS Tayside Medicines Governance Unit in conjunction with Mental Health Citalopram & escitalopram:QT interval prolongation New maximum daily dose restrictions, contraindications, and warnings Information has been issued via Drug Safety Update, Volume 5, Issue 5, December 2011 and ‘Dear Healthcare Professional Letters’ for both citalopram and escitalopram regarding new restrictions on the maximum daily doses, contraindications, and warnings. This is as a result of an assessment of a QT study that revealed dose-dependent increase in the QT interval observed with ECG monitoring for both citalopram and escitalopram. Maximum licensed daily doses for citalopram and escitalopram Adults Adults > 65 years Adults with hepatic impairment Citalopram 40 mg 20 mg 20 mg Escitalopram (non-formulary) 20 mg 10 mg 10mg The guidance in NHS Tayside is: ⇒ to review all patients on high dose* citalopram or escitalopram with aim of reducing to new maximum licensed doses ( * above new maximum licensed daily doses as stated in the table above) ⇒ not to prescribe citalopram or escitalopram with other medication known to prolong the QT interval ⇒ not to prescribe citalopram and escitalopram in patients with known QT prolongation or congenital long QT syndrome ⇒ to consider alternative antidepressant in patients with cardiac disease ( e.g. patients with significant bradycardia; recent myocardial infarction or decompensated heart failure) See flow diagram on page 3 for further guidance and table below on medicines known to prolong the QT interval. Medicines known to increase plasma levels of citalopram or escitalopram, e.g. omeprazole & some antivirals may require dose reduction of citalopram or escitalopram and should be used with caution. -

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH ELAVIL® Amitriptyline Hydrochloride Tablets

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH ELAVIL® amitriptyline hydrochloride tablets USP 10, 25, 50 and 75 mg Antidepressant AA PHARMA INC. DATE OF PREPARATION: 1165 Creditstone Road Unit #1 August 29, 2018 Vaughan, ON L4K 4N7 Control No.: 217626 1 PRODUCT MONOGRAPH ELAVIL® amitriptyline hydrochloride tablets USP 10, 25, 50, 75 mg THERAPEUTIC CLASSIFICATION Antidepressant ACTIONS AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Amitriptyline hydrochloride is a tricyclic antidepressant with sedative properties. Its mechanism of action in man is not known. Amitriptyline inhibits the membrane pump mechanism responsible for the re-uptake of transmitter amines, such as norepinephrine and serotonin, thereby increasing their concentration at the synaptic clefts of the brain. Amitriptyline has pronounced anticholinergic properties and produces EKG changes and quinidine-like effects on the heart (See ADVERSE REACTIONS). It also lowers the convulsive threshold and causes alterations in EEG and sleep patterns. Orally administered amitriptyline is readily absorbed and rapidly metabolized. Steady-state plasma concentrations vary widely and this variation may be genetically determined. Amitriptyline is primarily excreted in the urine, mostly in the form of metabolites, with some excretion also occurring in the feces. INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ELAVIL® (amitriptyline hydrochloride) is indicated in the drug management of depressive illness. ELAVIL® may be used in depressive illness of psychotic or endogenous nature and in selected patients with neurotic depression. Endogenous depression is more likely to be alleviated than are other depressive states. ELAVIL® ®, because of its sedative action, is also of value in alleviating the anxiety component of depression. As with other tricyclic antidepressants, ELAVIL® may precipitate hypomanic episodes in patients with bipolar depression. These drugs are not indicated in mild depressive states and depressive reactions. -

COPD Agents Review – October 2020 Page 2 | Proprietary Information

COPD Agents Therapeutic Class Review (TCR) October 1, 2020 No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage or retrieval system without the express written consent of Magellan Rx Management. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Magellan Rx Management Attention: Legal Department 6950 Columbia Gateway Drive Columbia, Maryland 21046 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended to be educational in nature and is intended to be used for informational purposes only. Send comments and suggestions to [email protected]. October 2020 -

Inappropriate Elimination Disorders

INAPPROPRIATE ELIMINATION DISORDERS What is “inappropriate elimination”? This is a term that means that a cat is urinating and/or defecating in the house but not in the litter box. What causes it? After medical causes of these problems have been ruled out, the source of the problem is considered a behavioral disorder. Behavioral causes of inappropriate elimination fall into two general categories: 1) a dislike of the litter box, and 2) stress-related misbehavior. Why would a cat not like its litter box? One of the main reasons for this is because the litter box has become objectionable to the cat. This usually occurs because it is not cleaned frequently enough or because the cat does not like the litter in it. The latter is called substrate aversion; it can occur because the litter was changed to a new, objectionable type or because the cat just got tired of the old litter. What stresses can cause inappropriate elimination? There are probably hundreds of these, but the more common ones are as follows: a) A new person (especially a baby) in the house b) A person that has recently left the house (permanently or temporarily) c) New furniture d) New drapes e) New carpet f) Rearrangement of the furniture g) Moving to a new house h) A new pet in the house i) A pet that has recently left the house j) A new cat in the neighborhood that can be seen by the indoor cat k) A cat in “heat” in the neighborhood l) A new dog in the neighborhood that can be heard by the indoor cat I feel that this is a problem that cannot be tolerated, even if the cat has to leave my house.