Constructing Identities Structure and Practice in the Early Bronze Age – Southwest Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gnr. 28 Dyrland

Gnr. 28 Dyrland. Oppdatert: mars2012. Oppdatering av noen av de familiene som har, eller har hatt, bosted på Dyrland. Ansvarlig: Leif Olsen . Oppdatert: Henry Oskar Forssell Rettelser og oppdateringer kan sendes til Slektsforum Karmøy. Bruksnr 1: Bygdebok for Skudenes og Skudeneshavn side 198. 2. 1673-1683: Jarle Torsteinsen født ca 1631, død før 1706 Sønn til Torstein Knutsen og Rannveig Mjølhus " Vea-bruk B *Ukjent ektefelle Barn: a) Svein født: ca 1665 " Vik-bnr 47 b) Jon født: ca 1670 " Langåker-bnr 1 c) Rasmus født: ca 1682 *** Bygdebok for Skudenes og Skudeneshavn side 198. 4. 1710-1732: Sjur Didriksen født ca 1663 , død ca 1732?, Sønn til Didrik Ivarsen og Malene Heinesdatter ” Jondal Gift i 1689 med Bol (Bothild) Sjursdatter født ca 1665, Datter til Sjur Andersen Haukanes og Susanne Andersdatter " Haukanes, Varaldsøy Barn: a) Didrik født: ca 1693 Gift 1.gang med Malene Andersdatter " Dale-bnr 1 b) Sjur født: ca 1698 Gift med enke Eli Nilsdatter " Grønnestad i Bokn c) Susanne født: ca 1700 Gift med Anders Hansen " Kirkeleite-bnr 1 d) Anders født: ca 1702 Gift med Anna Olsdatter " Hovdastad-bnr 2 *** Sjur kommer hit fra Åkra bnr 21, men hadde før det bodd på Espeland i Jondal, Hardanger Sjur er skoleholder og prestens medhjelper, men da den nye skoleordning skulle gjennomføres følte han seg så gammel at han foretrakk å slutte. Bygdebok for Skudenes og Skudeneshavn side 200. 8. 1793-1834: Rasmus Eriksen født ca 1771, død før 1842 Sønn til Erik Govertsen og Brita Olsdatter " Dyrland-bnr 4 Gift i 1796 Anna Larsdatter født 2 juli 1775, død 1860 Datter til Lars Sjursen og Berta Bårdsdatter " Søndre Vaage-bnr 1 Barn: a) Brita født: ca 1797 b) Erik født: ca 1800 Gift med Brita Olsdatter " Neste bruker c) Brita født: 1804 Døde ugift den 1 febr. -

'321 Du I.A.P

I.A.P. Rapporten 2 .'321 DU I.A.P. Rapporten uitgegeven door I edited by Prof Dr. Guy De Boe VIOE bibliotheek 5347 11111111 ~ • 1 l~ a " a l • 1 ' W.T A l V ediled :'-, ppori\-:n 2 Ze11il< 1997 Een uitgave van het Published by the Instituul voor het Archeologisch Patrimonium Institute for the Archaeological Heritage Wetenschappelijke instelling van de Scientific Institution of the Vlaamse Gemeenschap Flemish Community Departement Leefmilieu en Infrastructuur Department of the Environment and Infrastructure Administratie Ruimtelijke Ordening, Huisvesting Administration of Town Planning, Housing en Monumenten en Landschappen and Monuments and Landscapes Doornvcld Industrie Asse 3 nr. 1 1, Bus 30 B -1731 Zcllik- Asse Tcl: (02) 463. LU3 1- 32 2 -163 13 33) fax: (02) 463.19.'1 1-.12 2-163 19 511 DTP: Arpuco. Seer.: !Vi. Lauwaert & S. Van de Voorde. ISSN 13 72-0007 ISBN 90-75230-03-6 D/1997/6024/2 02 DEATH AND BURIAL- DE WERELD VAN DE DOOD-LE MONDE DE LA MORT- TOD UND BEGRA!!NIS was organized by Gisela Grupe werd georganiseerd door Willy Dezuttere fut organisee par wurde veranstaltet von PREFACE Death and some fonn of burial are common to all milians-Universitiit, Munchcn) and Willy Dezuttere humankind and the very nature of the disposal of (City of Bruges). Unfortunately, quite a few contri human remains as well as the behavioural patterns - butors to this section did submit a text in time for social, economic, political and even environmental - inclusion in the present volume. In addition, ceme linked with this important passage in human life teries played an important part in the development and makes it a subject of direct interest to archaeology. -

Prospectus in Connection with the Listing of Norwegian

*ÀëiVÌÕÃÊÊViVÌÊÜÌ ÊÌ iÊÃÌ}ÊvÊ ÀÜi}>Ê*À«iÀÌÞÊ-½ÃÊà >ÀiÃÊÊ"ÃÊ ©Àà - >ÀiÊÃÃÕiÊvÊLiÌÜiiÊ£x]äää]äääÊ>`ÊÓx]äää]äääÊ iÜÊ- >ÀiÃÊÊ >ÃÃÕ}ÊvÕÊiÝiÀVÃiÊvÊÌ iÊÀiià iÊ"«Ì® -iV`>ÀÞÊ->iÊvÊÕ«ÊÌÊÓÊäääÊäääÊ iÜÊ- >Àià `V>ÌÛiÊ*ÀViÊ,>}i\Ê "ÊxäÊqÊ "ÊxxÊ«iÀÊà >Ài LÕ`}Ê*iÀ`ÊvÀÊÌ iÊÃÌÌÕÌ>Ê"vviÀ}\ £Ê ÛiLiÀÊÓääÈÊÌÊ£ÎÊ ÛiLiÀÊÓääÈÊ>ÌÊ£x\ääÊ ÕÀÃÊ /® ««V>ÌÊ*iÀ`ÊvÀÊÌ iÊ,iÌ>Ê"vviÀ}\ £Ê ÛiLiÀÊÓääÈÊÌÊ£ÎÊ ÛiLiÀÊÓääÈÊ>ÌÊ£Ó\ääÊ ÕÀÃÊ /® / iÊ"vviÀÊ- >ÀiÃÊ >ÛiÊÌÊLiiÊ>`ÊÜÊÌÊLiÊÀi}ÃÌiÀi`ÊÕ`iÀÊÌ iÊ1°-°Ê-iVÕÀÌiÃÊVÌÊvÊ£ÎÎ]Ê>ÃÊ>i`i`ÊÌ iʺ1°-°Ê-iVÕÀÌiÃÊVÌ»®]Ê>`Ê>ÀiÊLi}ÊvviÀi` >`ÊÃ`Ê®ÊÊÌ iÊ1Ìi`Ê-Ì>ÌiÃÊÞÊÌʺµÕ>wi`ÊÃÌÌÕÌ>ÊLÕÞiÀû]Ê>ÃÊ`iwi`ÊÊ>`ÊÊÀi>ViÊÕ«Ê,ÕiÊ£{{ÊÕ`iÀÊÌ iÊ1°-°Ê-iVÕÀÌiÃÊVÌÆÊ>`Ê® ÕÌÃ`iÊÌ iÊ1Ìi`Ê-Ì>ÌiÃ]ÊÊÀi>ViÊÊ,i}Õ>ÌÊ-ÊÕ`iÀÊÌ iÊ1°-°Ê-iVÕÀÌiÃÊVÌ°Ê*ÀëiVÌÛiÊ«ÕÀV >ÃiÀÃÊ>ÀiÊ iÀiLÞÊÌwi`ÊÌ >ÌÊÃiiÀÃÊvÊ"vviÀÊ- >ÀiÃÊ>Þ LiÊÀiÞ}ÊÊÌ iÊiÝi«ÌÊvÀÊÌ iÊ«ÀÛÃÃÊvÊÃiVÌÊxÊvÊÌ iÊ1°-°Ê-iVÕÀÌiÃÊVÌÊ«ÀÛ`i`ÊLÞÊ,ÕiÊ£{{°Ê"vviÀÊ- >ÀiÃÊ>ÀiÊÌÊÌÀ>ÃviÀ>LiÊiÝVi«ÌÊ >VVÀ`>ViÊÜÌ ÊÌ iÊÀiÃÌÀVÌÃÊ`iÃVÀLi`Ê iÀiÊÕ`iÀÊ-iVÌÊÎ]ʺ-Ì>ÌiiÌÃÊ>`Ê«ÀÌ>ÌÊvÀ>ÌÊqÊ«ÀÌ>ÌÊvÀ>Ì»Ê>`Ê>Ê>««V>LiÊ>Üð ÌÊi>`Ê>>}iÀÃÊ>`ÊLÀÕiÀà i>`Ê>>}iÀ ÓÇÊ"VÌLiÀÊÓääÈ Prospectus – Norwegian Property ASA Table of Contents 1 SUMMARY........................................................................................................5 1.1 Introduction to Norwegian Property ......................................................................................... 5 1.2 Directors, senior management and employees.......................................................................... 8 1.3 Financial information............................................................................................................... -

Fjn 2007 SPA 01 038:Fjn 2007-SPA 01-038

Explore Fjord Norway 39 Páginas amarillas – contenido Transporte 41 Mapa ______________________ 40 Barcos rápidos ________________ 42 Ferrocarriles __________________ 44 Comunicaciones aéreas __________ 41 La Línea Costera Hurtigruten ______ 42 Carreteras de peaje ____________ 44 Transbordadores del Continente Transbordadores________________ 42 y de Gran Bretaña ______________ 41 Autobuses expresos ____________ 44 Información de viajes 45 Algunas ideas para la Noruega Lugares para vaciar caravanas Cámpings ____________________46 de los Fiordos ________________ 45 y autocaravanas ________________45 Información práctica ____________46 En coche por la Noruega Carreteras cerrados en invierno ____46 Temperaturas __________________47 de los Fiordos __________________45 Rutas donde se pueden dar tramos Impuesto del pescador __________47 El estándar de las carreteras ______ 45 de carretera estrecha y sinuosa ____46 Albergues juveniles Leyes y reglas ________________ 45 Alojamiento __________________46 en la Noruega de los Fiordos ______48 Límites de velocidad ____________45 Tarjeta de cliente de hoteles ______46 Casas de vacaciones ____________48 Vacaciones en cabañas __________46 Møre & Romsdal 49 Información general de la provincia 49 Kristiansund - Nordmøre ________ 51 Geirangerfjord - Trollstigen ______ 53 Molde & Romsdal - Trollstigen - La Ålesund - Sunnmøre ____________ 52 Carretera del Atlántico __________ 50 Sogn & Fjordane 55 Información general de la provincia 55 Balestrand ____________________ 62 Fjærland ______________________64 Stryn -

Western Karmøy, an Integral Part of the Precambrian Basement of South Norway

WESTERN KARMØY, AN INTEGRAL PART OF THE PRECAMBRIAN BASEMENT OF SOUTH NORWAY TOR BIRKELAND Birkeland, T.: Western Karmøy, an integral part of the Precambrian basement of south Norway. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 55, pp. 213-241. Oslo 1975. Geologically, the western side of Karmøy differs greatly from the eastern one, but has until recently been considered to be contemporaneous with the latter, i.e. of Caledonian age and origin. The rocks of western Karmøy often have a distinctly granitoid appearance, but both field geological studies and labora tory work indicate that most of them are in fact metamorphosed arenaceous rudites which have been subjected to strong regional metamorphism under PT conditions that correspond to the upper stability field of the amphibolite facies, whereas the Cambro-Ordovician rocks of the Haugesund-Bokn area to the east have been metamorphosed under the physical conditions of the green schist facies. From the general impression of lithology, structure, and meta morphic grade, the author advances the hypothesis that the rocks of western Karmøy should be related to a Precambrian event rather than to rock-forming processes that took place during the Caledonian orogeny. T. Birkeland, Liang 6, Auklend, 4000 Stavanger, Norway. Previous investigations The first detailed description of the rocks of western Karmøy was given by Reusch in his pioneer work from 1888. Discussing the mode of development of these rocks, he seems to have inclined to the opinion that the so-called 'quartz augen gneiss' and the other closely related rocks represent regionally metamorphosed clastic sediments. Additional information of the rocks con cerned is found in his paper from 1913. -

Annual Report 2004 Page 6

Annual Report IN 2004 WE DID IT WITH PURPOSE WILLP OWER What separates one bank from another? Interest rates, fees and products are often the same. But have you ever asked your bank what they want? Or what role they want to play? Our answer is simple. The objective of SpareBank 1 SR-Bank is to help create values for the region we are part of. Building a society is a everybody’s responsibility. In our region there are plenty of people that want to shoulder their share of work. The community spirit is more than a grand word. It is our philosophy. Everything we build, we build with a purpose. In January the moulds were ready page 12 In February they were picked as the country’s best youth-run business page 14 In March, RPT Production started bending page 16 In April, the network grew page 70 In May, Stavanger got a new stadium page 72 I J h t t d th ti hi Table of contents Page Page The SpareBank 1 SR-Bank Group 6 Primary capital certificates 63 Highlights 8 Key figures from the past five years 66 Principal figures 9 Value added statement 68 Key figures 9 Corporate governance 76 The Managing Director’s article 10 Risk and funds management The Annual Report 2004 18 in SpareBank 1 SR-Bank 81 Annual Accounts, table of contents 29 Overview of our offices 85 Profit and loss account 30 The business market division 90 Balance sheet 31 The private market division 93 Cash flow analysis 32 Our subsidiaries 100 Accounting principles 33 Human capital 102 Notes to the accounts 36 Organisational chart 108 The Auditor’s Report for 2004 62 Governing bodies -

Iconic Hikes in Fjord Norway Photo: Helge Sunde Helge Photo

HIMAKÅNÅ PREIKESTOLEN LANGFOSS PHOTO: TERJE RAKKE TERJE PHOTO: DIFFERENT SPECTACULAR UNIQUE TROLLTUNGA ICONIC HIKES IN FJORD NORWAY PHOTO: HELGE SUNDE HELGE PHOTO: KJERAG TROLLPIKKEN Strandvik TROLLTUNGA Sundal Tyssedal Storebø Ænes 49 Gjerdmundshamn Odda TROLLTUNGA E39 Våge Ølve Bekkjarvik - A TOUGH CHALLENGE Tysnesøy Våge Rosendal 13 10-12 HOURS RETURN Onarheim 48 Skare 28 KILOMETERS (14 KM ONE WAY) / 1,200 METER ASCENT 49 E134 PHOTO: OUTDOORLIFENORWAY.COM PHOTO: DIFFICULTY LEVEL BLACK (EXPERT) Fitjar E134 Husnes Fjæra Trolltunga is one of the most spectacular scenic cliffs in Norway. It is situated in the high mountains, hovering 700 metres above lake Ringe- ICONIC Sunde LANGFOSS Håra dalsvatnet. The hike and the views are breathtaking. The hike is usually Rubbestadneset Åkrafjorden possible to do from mid-June until mid-September. It is a long and Leirvik demanding hike. Consider carefully whether you are in good enough shape Åkra HIKES Bremnes E39 and have the right equipment before setting out. Prepare well and be a LANGFOSS responsible and safe hiker. If you are inexperienced with challenging IN FJORD Skånevik mountain hikes, you should consider to join a guided tour to Trolltunga. Moster Hellandsbygd - A THRILLING WARNING – do not try to hike to Trolltunga in wintertime by your own. NORWAY Etne Sauda 520 WATERFALL Svandal E134 3 HOURS RETURN PHOTO: ESPEN MILLS Ølen Langevåg E39 3,5 KILOMETERS / ALTITUDE 640 METERS Vikebygd DIFFICULTY LEVEL RED (DEMANDING) 520 Sveio The sheer force of the 612-metre-high Langfossen waterfall in Vikedal Åkrafjorden is spellbinding. No wonder that the CNN has listed this 46 Suldalsosen E134 Nedre Vats Sand quintessential Norwegian waterfall as one of the ten most beautiful in the world. -

Impulses of Agro-Pastoralism in the 4Th and 3Rd Millennia BC on The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Impulses of agro-pastoralism in the 4th and 3rd millennia BC on the south-western coastal rim of Norway Mari Høgestøl and Lisbeth Prøsch-Danielsen A review of the available archaeological and palaeoecological evidence from the coastal heathlands of south-western Norway was compiled to reveal the processes of neolithisation proceeding from the Early Neolithic towards the generally accepted breakthrough in the Late Neolithic, 2500/2350 cal. BC. South-western Norway then became part of the Scandinavian, and thus the European, agricultural complex. Three phases of forest clearance are recorded — from 4000–3600 cal. BC, 2500–2200 cal. BC and 1900–1400 cal. BC. Deforestation was intentional and followed a regional pattern linked to the geology and topography of the land. In the first period (4000–2500 cal. BC), forage from broad-leaved trees was important, while cereal cultivation was scarcely recorded. Agro-Neolithic (here referring to agriculturally-related Neolithic) artefacts and eco-facts belonging to the Funnel Beaker and Battle Axe culture are rare, but pervasive. They must primarily be considered to be status indicators with a ritual function; the hunter-gatherer economy still dominated. The breakthrough in agro-pastoral production in the Late Neolithic was complex and the result of interactions between several variables, i.e. a) deforestation resulting from agriculture being practised for nearly 1500 years b) experience with small-scale agriculture through generations and c) intensified exchange systems with other South Scandinavian regions. From 2500/2350 cal. -

Barnehagebruksplan 2021-2024

Barnehagebruksplan 2021-2024 1 Innhald Samandrag ............................................................................................. 5 Nasjonal barnehagepolitikk ..................................................................... 7 Full barnehagedekning ............................................................................................ 7 Maksimalpris ........................................................................................................... 7 Nasjonal kontantstøtte ............................................................................................. 7 Bemanning- og pedagognorm ................................................................................. 8 Likeverdig behandling ............................................................................................. 8 Kommuneplan 2014-2028 ..................................................................................... 10 Plassar og dekningsgrad ....................................................................... 12 Hå kommune samanlikna med andre kommunar .................................................. 12 Barnehagebygg og uteområde .............................................................. 15 Barnehagen i nærmiljøet ....................................................................................... 15 Barnehagebygga ................................................................................................... 15 Arbeidsplass for tilsette ........................................................................................ -

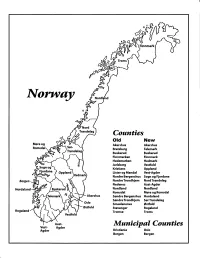

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

E39 ROGFAST Laupland - Knarholmen PLANBESKRIVELSE MED KONSEKVENSUTREDNING

Region vest Prosjektavdelingen 15. januar 2015 E39 ROGFAST Laupland - Knarholmen PLANBESKRIVELSE MED KONSEKVENSUTREDNING E39 ROGFAST, REGULERINGSPLAN FOR LAUPLAND – KNARHOLMEN, INKLUDERT TUNNEL OG VENTILASJONSTÅRN PÅ KRÅGA 2 E39 ROGFAST, REGULERINGSPLAN FOR LAUPLAND – KNARHOLMEN, INKLUDERT TUNNEL OG VENTILASJONSTÅRN PÅ KRÅGA 3 Forord E39 Rogfast innebærer fergefri kryssing av Boknafjorden og utbygging av E39 kyststamvegen. Utbyggingen vil gi en samlet reduksjon i reisetid på ca. 40 min i forhold til dagens situasjon. Statens vegvesen Region vest har satt i gang arbeidet med å utarbeide en ny reguleringsplan for E39 Rogfast i Bokn kommune, som gjelder tunnel og veg i dagen mellom Laupland og Knarholmen. Dette har sin bakgrunn i Statens vegvesen Vegdirektoratets beslutning om at tunnelen må bygges med slakere stigning enn tidligere forutsatt. Planarbeidet omfattes av "Forskrift om konsekvensutredninger", og det ble ved oppstart av reguleringsplanarbeidet utarbeidet planprogram. Planprogrammet la føringer for planprosessen, for hvilket alternativ som skal reguleres og for hvilke temaer som skulle utredes nærmere i konsekvensutredningen. Statens vegvesen er tiltakshaver og Bokn kommune er planmyndighet. COWI AS har vært engasjert av Statens vegvesen for å bistå i utarbeidelse av reguleringsplan og konsekvensutredning. E39 ROGFAST, REGULERINGSPLAN FOR LAUPLAND – KNARHOLMEN, INKLUDERT TUNNEL OG VENTILASJONSTÅRN PÅ KRÅGA 4 INNHOLD Forord 3 1 Innledning 6 1.1 Bakgrunn 6 1.2 Formålet med planen 8 2 Planprosess 9 2.1 Varsel om oppstart 10 2.2 Planprogram -

56163 Årsrapp RG 2017.Indd

Årsrapport 2017 Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal og Sirdal Innhold Reiselivsdirektøren har ordet 4 Ansatte og styret 6–11 Styrets årsberetning 2017 10 Tiltakene i 2017 12 Generell markedsutvikling i 2017 14 Kommunikasjon 18 Kongress- og arrangementsturisme 30 Ferie og fritid 44 Vertskap 54 Årsregnskap 2017 58 Resultatregnskap 2017 60 Balanse 2017 61 Noter 62 Revisjonsberetning 64 Medlemmer i 2017 66 Foto forside: Fjøløy Fyr. © Monica Larsen. Bakgrunnsfoto: MS Rapp kid dog dad. Foto © Gunhild Vevik. Reiselivsdirektøren har ordet 4 Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal og Sirdal Finnøy, Rennesøy, Randaberg, Stavanger, Sandnes, Sola, Gjesdal, Klepp, Time, Hå, Bjerkreim, Eigersund, Lund, Sokndal og Sirdal 5 Reiselivs direktøren har ordet Foto: © Monica Larsen Adventure tourism er i sterk vekst og det forventes at dette segmentet vil ha hele 50% av markedet i 2020. Det er derfor meget gledelig å se hvordan regionen er i ferd med å ta posisjon med stadig nye / Region Stavanger opplevelsesaktører som etablerer seg med nye spennende opplevelsesprodukter. Ikke minst er det også en styrke at allerede etablerte aktører vokser og går fra sesong til helårsbedrift, og har en rekke nye produkter tilpasset høst, vinter og vår. Denne utviklingen er helt avgjørende for at vi skal lykkes i vårt mål med å bli en bærekraftig helårsdestinasjon. Gode sammensatte reiselivsopplevelser på tvers av kommunegrensene styrker vår posisjon og fokus på å kommersialisere nye produktpakker for salg, er avgjørende for verdiskapningen. Region Stavanger har bistått som rådgivere i sentrale utviklingsprosjekter som Jærmalerprosjektet, Dalane Kyststi og Trollpikken.