Churchill and Britain's 'Financial Dunkirk'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leadership and Change: Prime Ministers in the Post-War World - Alec Douglas-Home Transcript

Leadership and Change: Prime Ministers in the Post-War World - Alec Douglas-Home Transcript Date: Thursday, 24 May 2007 - 12:00AM PRIME MINISTERS IN THE POST-WAR WORLD: ALEC DOUGLAS-HOME D.R. Thorpe After Andrew Bonar Law's funeral in Westminster Abbey in November 1923, Herbert Asquith observed, 'It is fitting that we should have buried the Unknown Prime Minister by the side of the Unknown Soldier'. Asquith owed Bonar Law no posthumous favours, and intended no ironic compliment, but the remark was a serious under-estimate. In post-war politics Alec Douglas-Home is often seen as the Bonar Law of his times, bracketed with his fellow Scot as an interim figure in the history of Downing Street between longer serving Premiers; in Bonar Law's case, Lloyd George and Stanley Baldwin, in Home's, Harold Macmillan and Harold Wilson. Both Law and Home were certainly 'unexpected' Prime Ministers, but both were also 'under-estimated' and they made lasting beneficial changes to the political system, both on a national and a party level. The unexpectedness of their accessions to the top of the greasy pole, and the brevity of their Premierships (they were the two shortest of the 20th century, Bonar Law's one day short of seven months, Alec Douglas-Home's two days short of a year), are not an accurate indication of their respective significance, even if the precise details of their careers were not always accurately recalled, even by their admirers. The Westminster village is often another world to the general public. Stanley Baldwin was once accosted on a train from Chequers to London, at the height of his fame, by a former school friend. -

George Edward) Lord Peter Thorneycroft Oral History Interview –JFK #1, 6/19/1964 Administrative Information

(George Edward) Lord Peter Thorneycroft Oral History Interview –JFK #1, 6/19/1964 Administrative Information Creator: (George Edward) Lord Peter Thorneycroft Interviewer: Robert Kleiman Date of Interview: June 19, 1964 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 23 pp. Biographical Note Thorneycroft, (George Edward) Lord Peter; Minister of Aviation (1960-1962); Minister of Defence (1962-1964); Secretary of State for Defence, United Kingdom (1964). Thorneycroft discusses his interactions with John F. Kennedy [JFK] and JFK’s way of creating organic conversation. He covers the relationships between Britain, Europe, and the United States, joint weapon production, and the discussions that were held in Nassau, among other issues. Access Restrictions No restrictions. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed May 13, 1965, copyright of these materials has passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Notes on Contributors

129 Cercles 37 (2020) Notes on Contributors The Right Honourable Gordon Brown was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. Prior to that he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer for ten years. He was educated at the University of Edinburgh and was Member of Parliament for Kirkaldy and Cowdenbeath for thirty-two years. John Campbell is a freelance historian and political biographer. His first book, Lloyd George : The Goat in the Wilderness, published in 1977, arose out of Paul Addison 's final-year honours course on British politics between the wars and was essentially his Ph.D thesis, supervised by Paul and examined by A.J.P. Taylor. Since then he has written full-scale biographies of F.E. Smith (1983), Aneurin Bevan (Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism, 1987), Edward Heath (Winner of the 1994 NCR Book Award for Non-Fiction), Margaret Thatcher (The Grocer's Daughter, 2000, and The Iron Lady, 2003), and Roy Jenkins (A Well-Rounded Life, 2014), as well as If Love Were All ... The Story of Frances Stevenson and David Lloyd George (2006) and Pistols at Dawn : Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown (2009) and numerous book reviews and other articles and essays in various publications over the years. David Freeman is editor of Finest Hour, the journal of the International Churchill Society. He teaches history at California State University, Fullerton. In addition to having published contributions by Paul Addison in Finest Hour, he once had the privilege of driving Addison across a wide stretch of Texas. -

Winston Churchill's "Crazy Broadcast": Party, Nation, and the 1945 Gestapo Speech

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Winston Churchill's "crazy broadcast": party, nation, and the 1945 Gestapo speech AUTHORS Toye, Richard JOURNAL Journal of British Studies DEPOSITED IN ORE 16 May 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/9424 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication The Journal of British Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/JBR Additional services for The Journal of British Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Winston Churchill's “Crazy Broadcast”: Party, Nation, and the 1945 Gestapo Speech Richard Toye The Journal of British Studies / Volume 49 / Issue 03 / July 2010, pp 655 680 DOI: 10.1086/652014, Published online: 21 December 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0021937100016300 How to cite this article: Richard Toye (2010). Winston Churchill's “Crazy Broadcast”: Party, Nation, and the 1945 Gestapo Speech. The Journal of British Studies, 49, pp 655680 doi:10.1086/652014 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/JBR, IP address: 144.173.176.175 on 16 May 2013 Winston Churchill’s “Crazy Broadcast”: Party, Nation, and the 1945 Gestapo Speech Richard Toye “One Empire; One Leader; One Folk!” Is the Tory campaign master-stroke. As a National jest, It is one of the best, But it’s not an original joke. -

'Why Tories Won: Accounting for Conservative Party Electoral

'Why Tories Won: Accounting for Conservative Party Electoral Success from Baldwin to Cameron' Dr Richard Carr, Churchill College, Cambridge - 15 November 2012 [email protected] Thank you Allen for that kind introduction. Thank you too, of course, to Jamie Balfour and the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust for the support that enabled the research that I will lay out in part today. The research grant was extremely valuable for an early career academic – providing the means to support archival research that still informs my work some two years later, which has borne fruit in three of the articles that will be referred to at the bottom of the slides behind me, and in three monographs on twentieth century British politics I am due to publish in 2013. 6 publications and counting therefore owe part of their genesis to this grant, not withstanding the good work of my two sometime co-authors throughout this period, Dr Bradley Hart (a former PhD student here at Churchill College and current lecturer at California State University Fresno), and Rachel Reeves MP.1 By final way of preamble I must also thank the staff here at the Churchill Archives Centre, and indeed the Master, for various kindnesses over the years – not least in relation to a conference Bradley and I played a small role in coordinating in November 2010, during my By-Fellowship.2 So, today’s lecture is entitled ‘Why Tories Won: Accounting for Conservative Party Electoral Success from Baldwin to Cameron.’ Now, given Stanley Baldwin became Conservative Party leader in 1923, and David Cameron – Boris and the electorate permitting – seems likely to serve until at least 2015, that is quite an expanse of time to cover in 40 minutes, and broad brush strokes – not to say, missed policy areas - are inevitable. -

CONCLUSIONS of a Meeting of the Cabinet Held at Admiralty House, S.W

Declassified: Her Britannic Majesty’s Government SECRET on Southern Cameroons. Retyped in parts from Ambazonian Archives THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HER BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT _________________________________________________________________________________________ Printed for the Cabinet June 1961 _________________________________________________________________________________________ C.C. (61) 01st Conclusion Copy No 48 CABINET CONCLUSIONS of a Meeting of the Cabinet held at Admiralty House, S.W. 1, on Tuesday, 13th June, 1961, at 1030 a.m. Present The Right Hon. HAROLD MACMILLAN, M.P., Prime Minister The Right Hon. R. A. BUTLER, MP., The Right Hon. VISCOUNT KILMUIR, Secretary of State for the Home Lord Chancellor Department (Items 1-7) The Right Hon. SELWYN LLOYD, Q.C., M.P., The Right Hon. VISCOUNT HAILSHAM, Chancellor of the Exchequer Q.C., Lord President of the Council and Minister for Science The Right Hon. JOHN MACLAY, MP., The Right Hon. DUNCAN SANDYS, M.P., Secretary of State for Scotland Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations (Items 1-8) The Right Hon. IAIN MACLEOD, M.P., The Right Hon. HAROLD WATKINSON, M.P., Secretary of State for the Colonies Minister of Defence The Right Hon. Sir DAVID ECCLES, The Right Hon. PETER THORNEYCROFT, M.P., M.P., Minister of Education Minister of Aviation The Right Hon. LORD MILLS, Pay- The Right Hon. REGINALD MAUDLING, M.P., master-General President of the Board of Trade The Right Hon. JOHN HARE, M.P., The Right Hon. EDWARD HEATH, M.P., Minister of Labour Lord Privy Seal Dr. The Right Hon. CHARLES HILL, The Right Hon. ERNEST MARPLES, M.P., M.P., Chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster Minister of Transport The Right Hon. -

The Dilemma of NATO Strategy, 1949-1968 a Dissertation Presented

The Dilemma of NATO Strategy, 1949-1968 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Robert Thomas Davis II August 2008 © 2008 Robert Thomas Davis II All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation titled The Dilemma of NATO Strategy, 1949-1968 by ROBERT THOMAS DAVIS II has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by ______________________________ Peter John Brobst Associate Professor of History ______________________________ Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences iii Abstract DAVIS, ROBERT THOMAS II, Ph.D., August 2008, History The Dilemma of NATO Strategy, 1949-1968 (422 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Peter John Brobst This study is a reappraisal of the strategic dilemma of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in the Cold War. This dilemma revolves around the problem of articulating a strategic concept for a military alliance in the nuclear era. NATO was born of a perceived need to defend Western Europe from a Soviet onslaught. It was an imperative of the early alliance to develop a military strategy and force posture to defend Western Europe should such a war break out. It was not long after the first iteration of strategy took shape than the imperative for a military defense of Europe receded under the looming threat of thermonuclear war. The advent of thermonuclear arsenals in both the United States and Soviet Union brought with it the potential destruction of civilization should war break out. This realization made statesmen on both sides of the Iron Curtain undergo what has been referred to as an ongoing process of nuclear learning. -

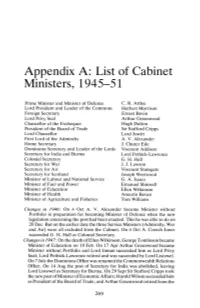

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office. -

'The Fools Have Stumbled on Their Best Man by Accident': an Analysis of the 1957 and 1963 Conservative Party Leadership Selections

University of Huddersfield Repository Miller, Stephen David 'The fools have stumbled on their best man by accident' : an analysis of the 1957 and 1963 Conservative Party leadership selections Original Citation Miller, Stephen David (1999) 'The fools have stumbled on their best man by accident' : an analysis of the 1957 and 1963 Conservative Party leadership selections. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/5962/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ 'TBE FOOLS HAVE STLUvMLED ON TIHEIR BEST MAN BY ACCIDENT': AN ANALYSIS OF THE 1957 AND 1963 CONSERVATIVE PARTY LEADERSHIP SELECTIONS STEPBEN DAVID MILLER A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirementsfor the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy The Universityof Huddersfield June 1999 MHE FOOLS HAVE STUNIBLED ONT]HEIR BEST MAN BY ACCIDENT': AN ANALYSIS OF THE 1957AND 1963CONSERVATIVE PARTY LEADERSHIP SELECTIONS S.D. -

In the Simplistic and Sometimes Pernicious Categorisations Which Have So Often Been Applied to the Political Personalities of Th

a LIberaL witHout a Home The Later Career oF Leslie Hore-belisHa In the simplistic and sometimes pernicious categorisations which have so often been applied to the political personalities of the 1930s – appeasers and anti-appeasers, a majority of dupes and a minority of the far-sighted, the decade’s Guilty Men and its isolated voices in the wilderness – Leslie Hore-Belisha has strong claims to be listed among the virtuous. David Dutton tells the story of Hore-Belisha – a Liberal without a home. 22 Journal of Liberal History 65 Winter 2009–10 a LIberaL witHout a Home The Later Career oF Leslie Hore-belisHa rue, he was a member Belisha ticked most of the right his name. Promoted to be Secre- of the National Gov- boxes. tary of State for War when Nev- ernment for most of its The events of January 1940 ille Chamberlain became Prime existence and a Cabinet represented the abrupt termina- Minister in May 1937, Belisha set minister from Octo- tion of an apparently inexora- about reforming the entrenched Tber 1936 until January 1940. But ble political ascent. Isaac Leslie upper echelons of the army and he was also a vigorous Minister Hore-Belisha was born in 1893, He was also War Office. During nearly three of War, who implemented a suc- the son of Jacob Isaac Belisha, a a vigorous years in this key post, he enhanced cession of much-needed reforms; businessman of Sephardic Jew- his standing with the public but he became disillusioned before ish origins. His father died when minister inevitably trod on many signifi- most of his colleagues with what Leslie was only nine months old cant and sensitive toes. -

2006 PSA Awards Ceremony Poll Ratings of Post-War Chancellors

2006 PSA Awards Ceremony Poll Ratings of post-war Chancellors Q For each of the following Chancellors of the Exchequer, please indicate how successful or unsuccessful you think each were overall while in office? Mean rating Gordon Brown 7.9 Stafford Cripps 6.1 Kenneth Clarke 6.1 Roy Jenkins 6.0 Hugh Dalton 5.7 Rab Butler 5.7 Harold Macmillan 5.4 Hugh Gaitskell 5.4 Denis Healey 5.0 Nigel Lawson 4.9 Base: 283 PSA members (13 Sept – 31 Oct 2006) Source: Ipsos MORI 2 Ratings of post-war Chancellors Q For each of the following Chancellors of the Exchequer, please indicate how successful or unsuccessful you think each were overall while in office? Mean rating Geoffrey Howe 4.5 James Callaghan 4.5 Peter Thorneycroft 4.0 Reginald Maudling 3.9 Ian Macleod 3.9 Derek Heathcoat-Amory 3.8 John Major 3.7 John Selwyn-Lloyd 3.6 Anthony Barber 2.9 Norman Lamont 2.3 Base: 283 PSA members (13 Sept – 31 Oct 2006) Source: Ipsos MORI 3 Providing economic stability Q Which of the two following Chancellors do you think were most successful at providing the country with economic stability? Top answers Gordon Brown 80% Kenneth Clarke 32% Rab Butler 14% Stafford Cripps 10% Hugh Dalton 9% Roy Jenkins 9% Nigel Lawson 9% Geoffrey Howe 6% Harold Macmillan 3% Denis Healey 3% Base: 283 PSA members (13 Sept – 31 Oct 2006) Source: Ipsos MORI 4 Leaving a lasting legacy Q Which of the two following Chancellors do you think were most successful at leaving a lasting legacy on Britain’s economy? Top answers Gordon Brown 42% Nigel Lawson 27% Geoffrey Howe 20% Kenneth Clarke 17% -

Dependence and Independence: Malta and the End of Empire1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM Journal of Maltese History, 2008/1 33 Dependence and independence: Malta and the end of empire 1 Simon C. Smith Professor, Department of History, University of Hull. Abstract The end of empire was rarely a neat or seamless process. Elements of empire often persisted despite the severance of formal constitutional ties. This was particularly so in the case of Malta which maintained strong financial and military links with Britain long after formal independence in 1964. Attempts to effect the decolonisation of Malta through integration with Britain in the 1950s gave way to more conventional constitution-making by the early 1960s. British attempts to retain imperial interests beyond the end of formal empire were answered by Maltese determination to secure financial and other benefits as a quid pro quo for tolerating close ties with the former imperial power. By the early 1970s, however, Britain wearied of the demands placed upon it by the importunate Maltese, preferring instead to try and pass responsibility for supporting Malta onto its NATO allies. Reflecting a widely held view in British governing circles, Sir Herbert Brittain of the Treasury remarked in mid-1955 that Malta could ‘never be given Commonwealth status, because of defence considerations’.2 Indeed, Malta’s perceived strategic importance, underlined during the Second World War, coupled with its economic dependence on Britain, apparently made independence a distant prospect. Despite the significant constitutional advances in the early 1960s, strong ties between Britain and Malta, especially in the military and financial spheres, endured beyond formal Maltese independence in 1964.