Using Bus Boarding Data to Identify Roles for Transport Providers Within Contextual Safeguarding Systems - Accepted for Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traveling Airport Mascot

A CORPORATE PUBLIcaTION BY THE AUGUSTA REGIONAL AIRPORT Mascot • Boarding Pass goes MoBile • Parking shuttle WINTER 2014 AGS Introduces a Traveling Airport Mascot Augusta Regional Airport (AGS) has initiated a new Airport Mascot Program. This program has been established to honor AGS’s former canine employee, Mayday. Mayday was AGS’s longtime employee who spent ten years keeping airport passengers safe by chasing birds and other wildlife off and away from the runways. She will be represented by two traveling plush border collie rides with pilots and/or passengers The two mascots will be posting companions, Mayday and Little Miss transiting through general aviation pictures, videos and comments from Mayday. Together these two travelers terminals located in airports around their travels on their social media will promote the love of aviation in the world. channels so anyone who is interested may follow their adventures. the hearts of the young and old alike! Little Miss Mayday will temporarily Mayday will hitchhike with the goal be adopted out to select youngsters of visiting all 50 states in the U.S. and within the CSRA to accompany For details on the 10 different countries. She will hitch them on their family vacation. Mayday Mascot Students first through eighth grade Program with interest in participating in the please visit program must submit a one page www.FlyAGS.com/Mayday essay stating why they believe Little or call Lauren Smith, AGS’s Miss Mayday should accompany Communications Manager them on their family’s next vacation. at (706) 798-3236. Holiday Spirit • Holiday ExoduS • Military HoSpitality facElift WintEr 2014 Mobile Boarding Passes Make Travel Easy at AGS! Due to the influx of requests for digital boarding passes electronic boarding pass upon arrival. -

Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual (Part B)

7UDQVLW&DSDFLW\DQG4XDOLW\RI6HUYLFH0DQXDO PART 2 BUS TRANSIT CAPACITY CONTENTS 1. BUS CAPACITY BASICS ....................................................................................... 2-1 Overview..................................................................................................................... 2-1 Definitions............................................................................................................... 2-1 Types of Bus Facilities and Service ............................................................................ 2-3 Factors Influencing Bus Capacity ............................................................................... 2-5 Vehicle Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-5 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-13 Fundamental Capacity Calculations .......................................................................... 2-15 Vehicle Capacity................................................................................................... 2-15 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-22 Planning Applications ............................................................................................... 2-23 2. OPERATING ISSUES............................................................................................ 2-25 Introduction.............................................................................................................. -

Why Some Airport-Rail Links Get Built and Others Do Not: the Role of Institutions, Equity and Financing

Why some airport-rail links get built and others do not: the role of institutions, equity and financing by Julia Nickel S.M. in Engineering Systems- Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2010 Vordiplom in Wirtschaftsingenieurwesen- Universität Karlsruhe, 2007 Submitted to the Department of Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Political Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2011 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2011. All rights reserved. Author . Department of Political Science October 12, 2010 Certified by . Kenneth Oye Associate Professor of Political Science Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Roger Peterson Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science Chair, Graduate Program Committee 1 Why some airport-rail links get built and others do not: the role of institutions, equity and financing by Julia Nickel Submitted to the Department of Political Science On October 12, 2010, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Political Science Abstract The thesis seeks to provide an understanding of reasons for different outcomes of airport ground access projects. Five in-depth case studies (Hongkong, Tokyo-Narita, London- Heathrow, Chicago- O’Hare and Paris-Charles de Gaulle) and eight smaller case studies (Kuala Lumpur, Seoul, Shanghai-Pudong, Bangkok, Beijing, Rome- Fiumicino, Istanbul-Atatürk and Munich- Franz Josef Strauss) are conducted. The thesis builds on existing literature that compares airport-rail links by explicitly considering the influence of the institutional environment of an airport on its ground access situation and by paying special attention to recently opened dedicated airport expresses in Asia. -

Medical Priority Ferry Loading Request Send This Completed Form to the Following Address at Least Two Weeks Before the Requested Date(S): Pierce County Ferry, 2702 S

Medical Priority Ferry Loading Request Send this completed form to the following address at least two weeks before the requested date(s): Pierce County Ferry, 2702 S. 42nd St., Ste. 201, Tacoma, WA 98409. When a vehicle occupant indicates through a physician that an extended wait to board the Pierce County ferry would cause detrimental health risks, that vehicle, with the occupants, may be allowed priority loading onto the ferry. This may be allowed when the affected person has provided this medical form signed by a physician indicating that such priority loading is advised. Note: 1. Medical appointments do NOT qualify. 2. Pierce County Ferry does not have medical facilities or trained medical practitioners on board any of its vessels. 3. Vehicle occupant must arrive at the ferry landing at least 20 minutes prior to the scheduled sailing time. For Physician Patient Name: Mailing Address: Phone: Email: Date(s) requested for priority loading: Make, color, and license number of vehicle: Priority loading requested: To Anderson Island From Anderson Island To Ketron Island From Ketron Island By signing below, physician attests that patient has a bona fide medical need for priority boarding on the date(s) indicated. Physician signature and title Date Name & location of practice Physician’s phone # For Ferry Administration Approved subject to: Authorized signature Date Instructions for Use 1. If you know the date of your scheduled surgery or procedure that would make extended waiting in ferry lines detrimental to your health, have your physician fill out and sign this form. Return the original form to our office at least 2 weeks prior to your procedure. -

Boarding-The-Ferry.Pdf

Welcome Please read this important information before boarding the ferry. For the Driver • You may park your vehicle in any of the four vehicle loading lanes (1 to 4). • After parking your vehicle, proceed to the Ferry Terminal to check-in and collect your boarding passes. • Following the vehicle loading announcement you should return to your vehicle and wait for our crew members’ loading instructions. You will need to present your boarding pass to the crew member. • Only the driver is to be present in the vehicle during loading. • Follow our crew member instructions when loading your vehicle. You may be required to drive on forward or reverse. Please pay particular attention to the crew on-board who will direct you to your parking spot. • If you think you may have difficulty boarding your vehicle, please ask a crew member to assist you. • Once you have your vehicle in position, you must ensure your car is in gear or in park and engage your parking brake. For Passengers • Please remain in or near the Ferry Terminal until the passenger boarding announcement is made. • Board the ferry as directed either via the passenger gate and ramp or via the air-bridge adjacent to the Terminal building. • Present your boarding pass to the crew member at the top of the gangway. • If you are taking a pet (dog) please board via the vehicle ramp and then proceed via the external stairs to the upstairs lounge area. An electric wheelchair is available. Please alert our team as early as possible if required. Cold drinks, snacks, light meals and great coffee are available to purchase inside the Ferry Terminals and also on board the ferries. -

The Role of Private-For-Hire Vehicles in Transit in Texas

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA/TX-07/0-5545-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date THE ROLE OF PRIVATE-FOR-HIRE VEHICLES IN TRANSIT IN October 2006 TEXAS Published: July 2007 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Jeffrey C. Arndt and Linda K. Cherrington Report 0-5545-1 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Texas Transportation Institute The Texas A&M University System 11. Contract or Grant No. College Station, Texas 77843-3135 Project 0-5545 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Texas Department of Transportation Technical Report: Research and Technology Implementation Office September 2005-August 2006 P. O. Box 5080 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Austin, Texas 78763-5080 15. Supplementary Notes Project performed in cooperation with the Texas Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration. Project Title: The Role of Private-for-Hire Vehicles in Texas Public Transit URL:http//tti.tamu.edu/documents/0-5545-1.pdf 16. Abstract This report updates prior national research related to the private-for-hire vehicle (PHV) industry. The first section of the report provides an overview of the PHV industry in Texas and the perspectives of transit providers, both within Texas and nationally, on the use of these businesses in operating transit services. The second section of the report contains five Texas case studies where PHV companies are providing demand - responsive, circulator, fixed-route replacement, and medical transportation services in support of public transit operators. -

A Two-Door Airplane Boarding Approach When Using Apron Buses

sustainability Article A Two-Door Airplane Boarding Approach When Using Apron Buses Camelia Delcea * , Liviu-Adrian Cotfas , Nora Chirit,ă and Ionut, Nica Department of Economic Informatics and Cybernetics, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, 010522 Bucharest, Romania; [email protected] (L.-A.C.); [email protected] (N.C.); [email protected] (I.N.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +40-769-652-813 Received: 3 September 2018; Accepted: 8 October 2018; Published: 10 October 2018 Abstract: Boarding is one of the major processes of airplane turnaround time, with a direct influence on the airline companies’ costs. From a sustainable point of view, a faster completion of the boarding process has impact not only on the airline company’s long-term performance, but also on customers’ satisfaction and on the airport’s possibility of offering more services without additional investments in new infrastructure. Considering the airplane boarding strategies literature, it can be observed that the latest papers are dealing with developing faster boarding strategies, most of them considering boarding using just one-door of the aircraft. Even though boarding on one-door might be feasible for the airports having the needed infrastructure and sufficient jet-bridges, the situation is different in European airports, as the use of apron buses is fairly common. Moreover, some of the airline companies have adapted their boarding pass in order to reflect which door one should board once they get down from the bus. While using these buses, the boarding strategies developed in the literature are hard to find their applicability. Thus, a new method for boarding on two-door airplanes when apron buses are used is proposed and tested against the actual boarding method. -

Fall Reopening K-12 Transportation Guidance

School Year 2020-21 Reopening Transportation Guidance July 22, 2020; updated February 11, 2021 Introduction and overview of guidance This transportation guidance supplements DESE’s Initial Fall School Reopening Memo. The initial memo put forth the goal of the safe return of as many students as possible to in-person school settings – as in-person school is the best way to ensure student learning and continued social and emotional growth. The safe transportation of students to and from school is a critical part of achieving this goal. In developing this transportation guidance, the health and safety of students and transportation staff remain our top priorities. This guidance focuses on supporting districts to develop a transportation strategy that provides safe conditions for all students and staff traveling by bus, while also maximizing in-person learning: 1. Follow the medically-advised health and safety requirements for school bus transportation summarized below and further described starting on page 7. 2. Address bus capacity challenges created by the physical distancing requirements on the school bus by considering strategies such as adding bus routes and staggering schedules if needed. 3. Take proactive steps to promote safe alternative transportation options for students, including family-provided transportation, walking, and biking, as appropriate. The Department developed the fall transportation guidance issued in July through collaboration with infectious disease physicians, pediatricians, and public health experts from Massachusetts General Brigham Health System and the Massachusetts Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics. We also consulted with the Massachusetts COVID-19 Command Center’s Medical Advisory Board, comprised of physicians and other health experts, which carefully reviewed the health and safety requirements for bus transportation outlined in this document. -

Final Report

Improving the Quality of Life by Enhancing Mobility University Transportation Center for Mobility DOT Grant No. DTRT06-G-0044 Intercity Passenger Rail: Implications for Urban, Regional, and National Mobility Final Report Benjamin R. Sperry and Curtis A. Morgan Performing Organization University Transportation Center for Mobility™ Texas Transportation Institute The Texas A&M University System College Station, TX Sponsoring Agency Department of Transportation Research and Innovative Technology Administration Washington, DC UTCM Project #11-10-75 December 2011 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. UTCM 11-10-75 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date December 2011 Intercity Passenger Rail: Implications for Urban, Regional, and National Mobility 6. Performing Organization Code Texas Transportation Institute 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Benjamin R. Sperry and Curtis A. Morgan UTCM 11-10-75 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) University Transportation Center for Mobility™ Texas Transportation Institute 11. Contract or Grant No. The Texas A&M University System 3135 TAMU DTRT06-G-0044 College Station, Texas 77843-3135 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Department of Transportation Final Report Research and Innovative Technology Administration January 2011-October 2011 th 400 7 Street, SW 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, D.C. 20590 15. Supplementary Notes Supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation, University Transportation Centers Program 16. Abstract Recent policy and regulatory actions by the U.S. government have revived interest in intercity passenger rail among transportation planners, policymakers, and the general public. -

One-Way Carsharing As a First and Last Mile Solution For

ONE-WAY CARSHARING AS A FIRST AND LAST MILE SOLUTION FOR TRANSIT Lessons from BCAA Evo Carshare in Vancouver Prepared by: Neha Sharma | UBC Sustainability Scholar | 2019 Prepared for: Mirtha Gamiz | Planner, New Mobility | TransLink Lindsay Wyant | Business Insights Analyst | BCAA Evo June 2020 This report was produced as part of the UBC Sustainability Scholars Program, a partnership between the University of British Columbia and various local governments and organisations in support of providing graduate students with opportunities to do applied research on projects that advance sustainability across the region. This project was conducted under the mentorship of TransLink and BCAA Evo staff. The opinions and recommendations in this report and any errors are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of TransLink, BCAA Evo or the University of British Columbia. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank the following individuals for their feedback and support throughout this project: Lindsay Wyant | Business Insights Analyst | BCAA Evo Mirtha Gamiz | Planner, New Mobility, Strategic Planning and Policy | TransLink Eve Hou | Manager, Policy Development, Strategic Planning and Policy | TransLink ii T ABLE OF C ONTENTS List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................. v Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. -

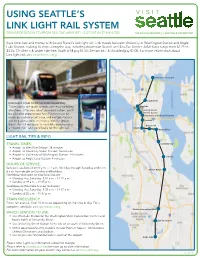

Using Seattle's Link Light Rail System

USING SEATTLE’S LINK LIGHT RAIL SYSTEM TRANSPORTATION TO/FROM SEA-TAC AIRPORT | 12 STOPS IN 37 MINUTES Save time, fuel and money with Sound Transit’s Link light rail! Link travels between University of Washington Station and Angle Lake Station, making 14 stops along the way, including downtown Seattle and Sea-Tac Airport. Adult fares range from $2.25 to $3.25; Children 5 & under ride free; Youth 6-18 pay $1.50; Seniors 65+ & Disabled pay $1.00. For more information about Link light rail, visit soundtransit.org. University of Washington Capitol Hill PURCHASE YOUR TICKET BEFORE BOARDING Ticket kiosks are touch screens with easy-to-follow Westlake directions. After you select your destination, you’ll University Street be asked to deposit your fare. Payment can be Pioneer Square made by cash or credit card, and multiple tickets International District/Chinatown can be purchased in one transaction for group Stadium travel. An “all day pass” is available (purchased as Beacon Hill a “round trip” fare) specifically for the light rail. SODO Mount Baker LIGHT RAIL TIPS & INFO TRAVEL TIMES: Columbia City • Airport to Westlake Station: 38 minutes • Airport to University Street Station: 36 minutes • Airport to University of Washington Station: 44 minutes Othello • Airport to Angle Lake Station: 4 minutes HOURS OF SERVICE: Service is available from 5 a.m. to 1 a.m. Monday through Saturday and from 6 a.m. to midnight on Sunday and holidays. Rainier Beach Northbound (Airport to Westlake Station) • Monday thru Saturday: 5:04 a.m. - 12:10 a.m. • Sunday: 6:19 a.m. -

A. Boarding Platform Height the Level-Boarding Platform, Which Is 14

A. Boarding Platform Height The level-boarding platform, which is 14 inches high, is considered the most desirable system in terms of passenger loading and unloading dwell times. This platform system is not feasible due to the configuration of Muni buses, as demonstrated by field tests which concluded a conflict between a 14-inch high platform and bus vehicle wheel lugs. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Capital Programs and Construction Division Other systems are unable to close the gap to the required 3 inches. In one study by the National Bus Rapid Transit Institute the Health Line in Cleveland achieved a minimum gap of 4 inches with average gaps of 8.11 and 5.92 inches depending on the station. The same study reported that the EmX BRT in Eugene Oregon achieved a minimum gap of 6.5 inches, with average gaps of 8.55 to 9.73 inches. EmX overcomes this gap by using bridge plates that deploy from the middle door. AC Transit plans a similar approach with bridge plates that deploy from doors other than the front doors. This prevents the use of all doors for boarding at the platforms since the front doors are blocked by railing to prevent confusion as to where wheelchairs should board. Considering the volume of passengers that the Van Ness BRT is expected to carry this approach is impractical. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Capital Programs and Construction Division Because the boarding islands are only available in the BRT corridor it would mean that wheelchair bound passengers boarding outside the BRT corridor would board at the front door.