Have Native Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus Kisutch) Persisted in the Nooksack and Samish Rivers Despite Continuous Hatchery Production Throughout the Past Century?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records and Thoughts by Evelyn Hopley Clift, 1964

Samish and Vendovia Islands : Records and Thoughts by Evelyn Hopley Clift, 1964 Samish Island Early Settlers It is much too late to learn the story of Samish Islands early history from the lips of the first pioneers. They are gone as are the Indians who once made the Island home, or an important rendezvous. But I have pieced together from the family Bible, old letters, several newspaper clippings of long ago and personal interviews with grandsons what tells a little part of those early days. I pass it on humbly, filled with awe at the courage, fortitude, strength and kindliness of the particular pioneer woman I found. Time and the humid climate have all but erased the signs which tell us that here was a white man's first crude cabin or there an Indian's smoky long-house. The clearings, so laboriously made, remain . greatly extended by tractor and bulldozer. Roads that are wide and smooth today were once native trails, then narrow pathways and wagon roads. Occasionally one comes upon a bit of orchard long forgotten, a portion of rotting rail fence, a wagon wheel, pestles, weights the natives used to anchor their nets, arrow heads, a lonely grave. One of the earliest settlements by white men in what is today Skagit County was on Samish Island. Projecting westward from the Samish River flats into the deep waters of Padilla and Samish Bays, the island is just over 3 miles long and 3/4 mile wide. It was originally separated from the mainland by Siwash Slough, so called for the 2000 or so Siwash who had their long-house there and hunted and fished these waters. -

Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits

PNNL-17161 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits Z Yang TP Khangaonkar December 2007 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor Battelle Memorial Institute, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or Battelle Memorial Institute. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. PACIFIC NORTHWEST NATIONAL LABORATORY operated by BATTELLE for the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Printed in the United States of America Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information, P.O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062; ph: (865) 576-8401 fax: (865) 576-5728 email: [email protected] Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Rd., Springfield, VA 22161 ph: (800) 553-6847 fax: (703) 605-6900 email: [email protected] online ordering: http://www.ntis.gov/ordering.htm This document was printed on recycled paper. -

SAMISH RIVER Geographic Response Plan (SAMR-GRP)

Northwest Area Committee JUNE 2017 SAMISH RIVER Geographic Response Plan (SAMR-GRP) SAMISH RIVER GRP JUNE 2017 SAMISH RIVER Geographic Response Plan (SAMR-GRP) June 2017 2 SAMISH RIVER GRP JUNE 2017 Spill Response Contact Sheet Required Notifications for Oil Spills & Hazardous Substance Releases Federal Notification ‐ National Response Center (800) 424‐8802* State Notification ‐ Washington Emergency Management Division (800) 258‐5990* ‐ Other Contact Numbers ‐ U.S. Coast Guard Washington State Sector Puget Sound (206) 217‐6200 Dept Archaeology & Historic Preservation (360) 586‐3065 ‐ Emergency / Watchstander (206) 217‐6001* Dept of Ecology ‐ Command Center (206) 217‐6002* ‐ Headquarters (Lacey) (360) 407‐6000 ‐ Incident Management (206) 217‐6214 ‐ NW Regional Office (Bellevue) (425) 649‐7000 13th Coast Guard District (800) 982‐8813 ‐ Bellingham Field Office (360) 715‐5200 National Strike Force (252) 331‐6000 Dept of Fish and Wildlife (360) 902‐2200 ‐ Pacific Strike Team (415) 883‐3311 ‐ Emergency HPA Assistance (360) 902‐2537* ‐ Oil Spill Team (360) 534‐8233* U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Dept of Health (800) 525‐0127 Region 10 – Spill Response (206) 553‐1263* ‐ Drinking Water (800) 521‐0323 ‐ Washington Ops Office (360) 753‐9437 Dept of Natural Resources (360) 902‐1064 ‐ RCRA / CERCLA Hotline (800) 424‐9346 ‐ After normal business hours (360) 556‐3921 ‐ Public Affairs (206) 553‐1203 Dept of Transportation (360) 705‐7000 State Parks & Recreation Commission (360) 902‐8613 National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration State Patrol ‐ District 7 (360) 654‐1204* Scientific Support Coordinator (206) 526‐6829 Weather (NWS Seattle) (206) 526‐6087 Tribal Contacts Samish Indian Nation (360) 293‐6404 Other Federal Agencies Upper Skagit Indian Tribe (360) 854‐7090 U.S. -

Final Geospatial Methodology Used in the Psnerp Comprehensive Change Analysis of Puget Sound Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem

FINAL GEOSPATIAL METHODOLOGY USED IN THE PSNERP COMPREHENSIVE CHANGE ANALYSIS OF PUGET SOUND PUGET SOUND NEARSHORE ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION PROJECT Prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District and Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife Prepared In Support of Prepared by Anchor QEA, LLC 1423 Third Avenue, Suite 300 Seattle, Washington 98101 In Association With Additional Anchor Team consultants and Salmon and Steelhead Habitat Inventory and Assessment Program Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission Point‐No‐Point Treaty Council Skagit River System Cooperative University of Washington Wetland Ecosystem Team May 2009 Table of Contents PREFACE BY THE PUGET SOUND NEARSHORE ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION PROJECT NEARSHORE SCIENCE TEAM .............................................................................................................. 1 1 INTRODUCTION AND PROCESS OVERVIEW............................................................................ 1 2 DATA DISCOVERY ............................................................................................................................ 3 3 DATABASE STRUCTURE ............................................................................................................... 10 3.1 Spatial Hierarchy, Scale, and Metrics.................................................................................... 11 3.2 Nested Spatial Components (Geographic Scale Units [GSUs])......................................... 13 3.2.1 Shoreline GSUs.................................................................................................................. -

Section 2. Hazard Summaries

Whatcom County SECTION 2: HAZARD SUMMARIES Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan SECTION 2. HAZARD SUMMARIES The following seven natural hazards were identified to be significant risks to the county, and specifically hazardous to the populated western areas of Whatcom County: 1. Earthquakes 2. Flooding 3. Geologic Hazards 4. Severe Storms 5. Tsunamis 6. Volcanoes 7. Wildland Fires The updated HIVA was received late in the plan update process and will be the basis for the next version of the all hazards plan. The following sections describe the seven significant natural hazards and their potential threats to Whatcom County. Much of the information collected in these hazard summaries came from local experts working in hazard assessment or hazard mitigation for a specific hazard. The summaries describe the hazards, convey the areas at potential risk from each hazard, and describe mitigation measures as implemented in the past or to be implemented in the future to manage the effects of natural disasters in Whatcom County. Each hazard description is organized into the following parts: Hazard Related Definitions Background Information General description of the hazard relevant to Whatcom County and Washington State History Historical background on the presence of the hazard in Whatcom County; much of this information was obtained from agencies such as FEMA, the Washington Department of Natural Resources (WDNR), and the U.S. Geological Society (USGS) Vulnerability Assessment Descriptions of specific areas within the county at risk for each hazard, when this information was available Mitigation Strategies Recommended mitigation strategies to lessen the dangers posed by each hazard Whatcom County Sheriff’s Office Division of Emergency Management Original Submission: June 1, 2015 2 - 1 FEMA Approval: Dec 15, 2016 Whatcom County SECTION 2: HAZARD SUMMARIES Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Whatcom County’s Planning and Development Services provided the entire hazard GIS datasets, except for the Wildland Fire data, which came from WDNR’s North Region. -

1. Skagit Basin Overview

1. Skagit Basin Overview Abstract Since the 1850s, the Skagit River basin has been altered by human activities such as logging, diking, and the construction of dams, roads, levees, and tide gates. Logging and construction of levees and dikes converted coniferous forest and wetlands to farmland, industrial, and urban/suburban residential development. Dams constructed in the Skagit River not only generate hydropower but also provide flood control, recreation opportunities, and diverse ecosystem services. Major highways constructed through Skagit County promoted both economic and population growth in Skagit County. These human developments have dramatically impacted the hydrology and geomorphology of the basin and have impacted or reduced habitat for a wide range of species, including multiple species of native anadromous fish historically reliant on Skagit River Basin tributaries. Low-lying farms, urban development, and other lands in the floodplain are currently vulnerable to river flooding and sea level rise. The economy of the Skagit River basin in the 19th and early 20th centuries was focused primarily on logging, mining, and agriculture, but has diversified through the second half of the 20th century. Rapid increases in population in the 21st century are projected for Skagit Co., which, under the Growth Management Act and the Skagit County Comprehensive Plan, will direct future growth primarily in urban areas. 1.1 Overview of the Skagit River Basin The Skagit River basin is located in southwestern British Columbia in Canada and northwestern Washington in the United States (Figure 1.1) and drains an area of 3,115 square miles (Pacific International Engineering, 2008). Major tributaries in the basin are the Baker River, Cascade River, and Sauk River. -

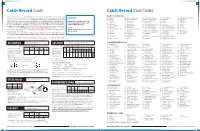

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142. -

Updating the River Mile System in Washington State: Considerations, Ramifications, and Recommended Solutions

GEOG 569 – SUMMER QUARTER, 2013 - CAPSTONE PROJECT UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON Updating the River Mile System in Washington State: Considerations, Ramifications, and Recommended Solutions Grant Novak Jon Walker 8/23/2013 GEOG 569 – CAPSTONE PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Problem Statement ............................................................................................................................. 2 II. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 2 III. The River Mile System ......................................................................................................................... 8 History ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Need for Updates ........................................................................................................................................ 9 IV. Proposed Alternatives .......................................................................................................................11 Alternative 1 – Keep current USGS river miles, and add major tributaries ..............................................11 Alternative 2 – Replace River Mile Dataset with NHD ..............................................................................12 Alternative 3 – Replace River Mile Dataset with NHD and develop online river miles application .........12 Financial Analysis -

Dedicated to Involving Our Community in Restoring Wild Salmon Populations for Future Generations

Dedicated to involving our community in restoring wild salmon populations for future generations. PHOTO: © 2012 JESSICA NEWLEY SKAGIT FISHERIES ENHANCEMENT GROUP 2012 ANNUAL REPORT Our mission is to build partnerships that educate and engage the community in habitat restoration and watershed stewardship in order to enhance salmonid populations. PO Box 2497 Phone: 360.336.0172 | Fax: 360.336.0701 1202 South 2nd Street, Suite C www.skagitfisheries.org Mount Vernon, WA 98273 Tax ID# 94-3165939 TO OUR FRIENDS PHOTO: © 2012 JESSICA NEWLEY Every day, the Skagit Fisheries Enhancement Group works hard with our community to improve habitat in our local watersheds for salmon. Most of our $1 million budget pays for on-the-ground habitat restoration, and in 2012 we had another great year creating new partnerships, working with old friends, and restoring over 50 acres of riparian and aquatic habitat. We are very excited about the new partnerships we established this past year, especially on Whidbey Island with the Northwest Straits Foundation, the Whidbey-Camano Land Trust, and the Island County Marine Resources Committee. We are enthused about the new possibilities these partnerships will help us realize in the island communities. In addition to on-the-ground habitat restoration projects, we continue to provide community outreach and youth education programs year ‘round throughout our local watersheds. Our staff and volunteers partner with an amazing group of educators, organizations and enthusiastic individuals to reach more members of our community every year. This year, we played a key role with other sponsors, partners and funders to put on the first-ever Skagit River Salmon Festival at Edgewater Park in Mount Vernon. -

2 SYSTEM DESCRIPTION 2.1 Introduction

2 SYSTEM DESCRIPTION 2.1 Introduction Skagit County is located in the northwestern part of Washington State, and stretches from Puget Sound to the crest of the Cascade Mountains. Also included are leeward islands of the San Juan Archipelago, together with the Skagit River delta and floodplain. The eastern two-thirds of Skagit County is dominated by the northern Cascade Mountains, which include Mount Baker, portions of North Cascade National Park, and Mount Baker National Forest. Mount Vernon is the largest city in Skagit County and the county seat. Other significant municipalities include Anacortes, Burlington, Concrete, Hamilton, LaConner, Lyman, and Sedro-Woolley. Figure 2-1 is a general vicinity map of Skagit County. As described in this chapter, the District operates the most expansive water system in the county with a total of over 23,000 active service connections. The majority of the District’s services are within the Judy Reservoir System (Judy System), Washington State Department of Health (DOH) Public Water System Identification (PWSID) 79500E, which serves Mount Vernon, Burlington, and Sedro-Woolley and surrounding rural and suburban areas. Appendix B contains the District’s Water Facilities Inventory for the Judy System, and Appendix C includes the most recent sanitary surveys of the Judy System and the water treatment plant. The District also operates remote water systems including the following: • Fidalgo Island (PWSID 00932 Y) • Alger (PWSID 01400 K) • Cedargrove (PWSID 11917 4) • Marblemount (PWSID AA642) • Mountain View (PWSID 03774 Y) • Potlatch Beach (PWSID 69034 L) • Rockport (PWSID 73600 6) • Skagit View Village (PWSID 96879 5) As directed by DOH, this WSP focuses on the District’s Judy Reservoir System because the satellite systems were addressed in the previous WSP update in 2007. -

NOOKSACK RIVER Geographic Response Plan (NOOR-GRP) NOOKSACK RIVER GRP JUNE 2017

Northwest Area Committee JUNE 2017 NOOKSACK RIVER Geographic Response Plan (NOOR-GRP) NOOKSACK RIVER GRP JUNE 2017 NOOKSACK RIVER Geographic Response Plan (NOOR-GRP) June 2017 2 NOOKSACK RIVER GRP JUNE 2017 Spill Response Contact Sheet Required Notifications for Oil Spills & Hazardous Substance Releases Federal Notification - National Response Center (800) 424-8802* State Notification - Washington Emergency Management Division (800) 258-5990* - Other Contact Numbers - U.S. Coast Guard Washington State Sector Puget Sound (206) 217-6200 Dept Archaeology & Historic Preservation (360) 586-3065 - Emergency / Watchstander (206) 217-6001* Dept of Ecology - Command Center (206) 217-6002* - Headquarters (Lacey) (360) 407-6000 - Incident Management (206) 217-6214 - Northwest Regional Office (Bellevue) (425) 649-7000 Station Bellingham (360) 734-1692 - Bellingham Field Office (360) 715-5200 13th Coast Guard District (800) 982-8813 Dept of Fish and Wildlife (360) 902-2200 National Strike Force (252) 331-6000 - Emergency HPA Assistance (360) 902-2537* - Pacific Strike Team (415) 883-3311 - Oil Spill Team (360) 534-8233* Dept of Health (800) 525-0127 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency - Drinking Water (800) 521-0323 Region 10 – Spill Response (206) 553-1263* - Shellfish Growing Areas (360) 789-8962 - Washington Ops Office (360) 753-9437 Dept of Natural Resources (360) 902-1064 - RCRA / CERCLA Hotline (800) 424-9346 - After normal business hours (360) 556-3921 - Public Affairs (206) 553-1203 Dept of Transportation (360) 705-7000 State Parks & Recreation Commission (360) 902-8613 National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration State Patrol - District 7 (360) 654-1204* Scientific Support Coordinator (206) 526-6829 Weather (NWS Seattle) (206) 526-6087 Tribal Contacts Lummi Nation (360) 312-2000 Other Federal Agencies Nooksack Indian Tribe (360) 592-5176 U.S. -

U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3406 Pamphlet

Prepared in cooperation with Whatcom County and the Washington State Department of Natural Resources Geomorphic Map of Western Whatcom County, Washington By Dori J. Kovanen, Ralph A. Haugerud, and Don J. Easterbrook Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3406 View to northeast across western Whatcom County. Lummi peninsula in foreground, Bellingham to right. Map image from Google, TerraMetrics, Landsat/Copernicus 2019. 2020 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2020 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Kovanen, D.J., Haugerud, R.A., and Easterbrook, D.J., 2020, Geomorphic map of western Whatcom County, Washington: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3406, pamphlet 42 p., scale 1:50,000, https://doi.org/10.3133/sim3406.