Notes Introductory to a Conference On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timothy Ferris Or James Oberg on 1 David Thomas on Eries

The Bible Code II • The James Ossuary Controversy • Jack the Ripper: Case Closed? The Importance of Missing Information Acupuncture, Magic, i and Make-Believe Walt Whitman: When Science and Mysticism Collide Timothy Ferris or eries 'Taken' James Oberg on 1 fight' Myth David Thomas on oking Gun' Published by the Comm >f Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION off Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAl (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts and Loren Pankratz, psychologist Oregon Health Toronto Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University of Miami Sciences Univ. Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Oregon Al Hibbs. scientist Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist, MIT Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, execu England Journal of Medicine understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky Indiana Univ Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Chicago consumer advocate. Allentown, Pa. and professor of history of science. Harvard Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor of Barry Beyerstein.* biopsychologist. -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

Historical Perspective

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 717–754, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Early Psychical Research Reference Works: Remarks on Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science Carlos S. Alvarado [email protected] Submitted March 11, 2020; Accepted July 5, 2020; Published December 15, 2020 DOI: 10.31275/20201785 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—Some early reference works about psychic phenomena have included bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and general over- view books. A particularly useful one, and the focus of the present article, is Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934). The encyclopedia has more than 900 alphabetically arranged entries. These cover such phenomena as apparitions, auras, automatic writing, clairvoyance, hauntings, materialization, poltergeists, premoni- tions, psychometry, and telepathy, but also mediums and psychics, re- searchers and writers, magazines and journals, organizations, theoretical ideas, and other topics. In addition to the content of this work, and some information about its author, it is argued that the Encyclopaedia is a good reference work for the study of developments from before 1933, even though it has some omissions and bibliographical problems. Keywords: Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science; Nandor Fodor; psychical re- search reference works; history of psychical research INTRODUCTION The work discussed in this article, Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934), is a unique compilation of information about psychical research and related topics up to around 1933. Widely used by writers interested in overviews of the literature, Fodor’s work is part of a reference literature developed over the years to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the early publications of the field by students of psychic phenomena. -

Apport from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Apport From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia An apport is the paranormal transference of an article from one place to another, or an appearance of an article from an unknown source.[1] Apports are often associated with poltergeist activity, and on rare occasions are said to be witnessed landing on the floor, in a person's lap or dropping from the ceiling. Flowers are a well known form of apport at spiritualistic séances, but tar and mud have also been reported.[2] Conversely, an asport is the transference of a small object from a known location to an unknown location via paranormal means.[3] As with all paranormal phenomena, apports are highly controversial, with critics such as Robert Todd Carroll saying that they are the result of magic tricks.[4] [edit] References 1. ^ http://parapsych.org/historical_terms.html Historical Terms Glossary of the Parapsychological Association, entry on Apport, Retrieved Sept 6, 2007 2. ^ Fontana, David (2005). Is There an Afterlife: A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence. Hants, UK: O Books, 352-381. ISBN 1903816904. 3. ^ Kentucky Paranormal Research. Retrieved on 2007-09-19. "An asport is any object the spirits or the medium makes disappear or teleports to another location." 4. ^ http://www.skepdic.com/apport.html Apport entry in the Skeptic's Dictionary by Robert Todd Carroll, retrieved June 19, 2008 [edit] See also Teleportation Cosmic Gospel that UFO cults receive by psychic transmission from "Space Brothers Apports are 'gifts' that manifests from non-physical to physical reality. Manifestation may be linked to teleportation or telekinesis by one or more of the people in the room. -

A Discussion of the Evidence That Personal Consciousness Persists After Death with Special Reference to Poltergeist Phenomena

pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Australian Journal of Parapsychology 2006, Volume 6, Number 1, pp. 5-20 A Discussion of the Evidence that Personal Consciousness Persists After Death with Special Reference to Poltergeist Phenomena WILLIAM ROLL Abstract: Humans have a dual mind, the mind of the left hemisphere and the mind of the right hemisphere. The left hemisphere has an organ for language and when awake can be conscious of things with linguistic labels. The right hemisphere is good at operating with mental images as in dreams. The functions of the right hemisphere include extrasensory perception and psychokinesis. However, the findings that have been advanced in favour of the idea that personality survives death have mostly been discussed in terms of the continuation of the left mind. This paper explores the pro and cons of this approach. THE TWO BRAIN HEMISPHERES AND THE IDEA OF SURVIVAL AFTER DEATH Following the lead of Frederic Myers (1903), the possibility of survival has been discussed in terms of the survival of personality, but with little attention to the organ where the idea of personality originates. Studies of the brain reveal that humans possess two very different personalities: the personality of the left-brain hemisphere and the personality of the right- brain hemisphere. Physiologically and psychologically each of us has a split personality. In the healthy individual the two sides of brain work together. In the simple act of walking, now it’s the right hemisphere and the left leg, then the left hemisphere and the right leg. -

Levity with Lifters

PSYCHIC VIBRATIONS ROBERT SHEAFFER IV; Levity with Lifters laims of anti-gravity keep pop- the testing surface." So says the Lifter effect, especially now that NASA and ping up all the time—it seems FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) sec- otJicr well-respected scientific authori- Cthat nothing will keep them tion on American Antigravity's Yahoo ties have experimented with it." (If you down. Robert L. Park exposed certain discussion group. purchase a physics textbook that does large aerospace companies' flirtation Now, lots of devices contain electrical describe this supposed "effect," I recom- with the so-called "Podkletnov gravity capacitors, but nobody expects to see mend that you return it as defective.) shield" (SI November/December 2002, them rising into the air. Ah, but you are However, it is indisputable that the p. 7), which has unfortunately not yet forgetting about the "Biefeld-Brown "lifters" really are rising into the air. The resulted in a gravity-shielded airliner. But according to a growing number of enthusiasts, "lifters" can use electric The lifters do indeed fly, charges to cancel gravity—and they give detailed instructions so that you can using the little-known build one of them in your own home! phenomenon of ion wind. (See http://groups.yahoo.coni/group/ americanantigravity/files/How-To- Documents/.) The leading promoter of "lifter tech- effect," named for its supposed discover- so-called "lifter effect" can be repeated nology" is the appropriately named ers Alfred Biefeld and T Townsend on demand, and does not conceal itself American Antigravity (www.american Brown, who founded the once-influen- from scrutiny by skeptics or hide from antigravity.com). -

010609 New Age Glossary-WEB

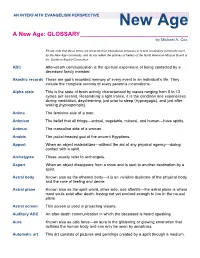

AN INTERFAITH EVANGELISM PERSPECTIVE New Age A New Age: GLOSSARY_________________________________ by Michael A. Cox Please note that these terms are presented for educational purposes to reveal vocabulary commonly used by the New Age community, and do not reflect the policies or beliefs of the North American Mission Board or the Southern Baptist Convention. ADC After-death communication is the spiritual experience of being contacted by a deceased family member. Akashic records These are god’s recorded memory of every event in an individual’s life. They include the complete records of every person’s incarnations. Alpha state This is the state of brain activity characterized by waves ranging from 8 to 13 cycles per second. Resembling a light trance, it is the condition one experiences during meditation, daydreaming, just prior to sleep (hypnagogic), and just after waking (hypnopompic). Anima The feminine side of a man. Animism The belief that all things—animal, vegetable, mineral, and human—have spirits. Animus The masculine side of a woman. Anubis The jackal-headed god of the ancient Egyptians. Apport When an object materializes—without the aid of any physical agency—during contact with a spirit. Archetypes These usually refer to archangels. Asport When an object disappears from a room and is sent to another destination by a spirit. Astral body Known also as the ethereal body—it is an invisible duplicate of the physical body, and the core of feeling and desire. Astral plane Known also as the spirit world, other side, and afterlife—the astral plane is where most souls exist after death, having not yet evolved enough to live in the causal plane. -

ESP Your Sixth Sense by Brad Steiger

ESP Your Sixth Sense By Brad Steiger Contents: Book Cover (Front) (Back) Scan / Edit Notes Inside Cover Blurb 1 - Exploring Inner Space 2 - ESP, Psychiatry, and the Analyst's Couch 3 - Foreseeing the Future 4 - Telepathy, Twins, and Tuning Mental Radios 5 - Clairvoyance, Cops, and Dowsing Rod 6 - Poltergeists, Psychokinesis, and the Telegraph Key in the Soap Bubble 7 - People Who See Without Eyes 8 - Astral Projection and Human Doubles 9 - From the Edge of the Grave 10 - Mediumship and the Survival Question 11 - "PSI" and Psychedelics, and Mind-Expanding Drugs 12 - ESP in the Space Age 13 - "PSI" Research Behind the Iron Curtain 14 - Latest Experiments in ESP 15 - ESP - Test It Yourself ~~~~~~~ Scan / Edit Notes Versions available and duly posted: Format: v1.0 (Text) Format: v1.0 (PDB - open format) Format: v1.5 (HTML) Format: v1.5 (PDF - no security) Genera: ESP / Paranormal / Psychic Extra's: Pictures Included (for all versions) Copyright: 1966 / 1967 First Scanned: August - 11 - 2002 Posted to: alt.binaries.e-book Note: 1. The Html, Text and Pdb versions are bundled together in one zip file. 2. The Pdf files are sent as a single zip (and naturally does not have the file structure below) ~~~~ Structure: (Folder and Sub Folders) Main Folder - HTML Files | |- {Nav} - Navigation Files | |- {PDB} | |- {Pic} - Graphic files | |- {Text} - Text File -Salmun ~~~~~~~ Inside Cover Blurb Have you ever played a "lucky" hunch? Ever had a dream come true? Received a call or letter from someone you "just happened" to think of? Felt that "I've been here before" sensation known as Deja vu? Sensed what was "about to happen" even an instant before it occurred? Known what someone was about to say - or perhaps even spoken the exact words along with him? Then You May Be Using Your Sixth Sense Your Esp Without Even Realizing It! Recent research indicates that almost everyone possesses latent ESP powers. -

Apport (Paranormal)

Apport (paranormal) 2020-07-03 BFOI Limited anser sig ha en vetenskaplig förklaring på det paranormala problemet med apporter. Vi kommer inte att här gå in på hur denna vetenskapliga förklaring ser ut, men om den föreslagna lösningen är korrekt kommer det att få stora konsekvenser för: 1) relationen mellan det paranormala och det vetenskapliga. 2) frågan om apporter är möjliga att automatisera. Bild ovan/Picture above: Lajos Pap (i mitten/middle), bedrägligt apportmedium/fraudulent apport medium. BFOI Limited arbetar för närvarande nästan uteslutande med denna fråga. Vad vi kunnat konstatera är att apporter är möjliga. Vi har likaså kunnat konstatera att även om apporter kan tyckas vara slumpmässiga är detta inte fallet. Den fråga som nu är av intresse är därför om apporterna är möjliga att styra på något sätt. Nedan återfinns på engelska, som bakgrund till problemet med apporter, vad Wikipedia har att säga om dessa paranormala förflyttningar. In English BFOI Limited considers itself to have a scientific explanation for the paranormal problem of apports. Here we will not go into what this scientific explanation looks like, but if the proposed solution is correct it will have major consequences for: 1) the relationship between the paranormal and the scientific. 2) the issue if apports are possible to automate. BFOI Limited is currently working almost exclusively on this issue. What we have been able to conclude is that apports are possible. We have also been able to conclude that, although apports may appear to be random, this is not the case. The question that is now of interest is therefore whether the apports are possible to control in any way. -

Eusapia Palladino, the Queen of the Cabinet Part 1

NOTES ON A STRANGE WORLD MASSIMO POLIDORO Eusapia Palladino, the Queen of the Cabinet Part 1 usapia Palladino is considered to her account, was able to stimulate spon- Genoa, and so on, where she was tested have been one of the most gifted taneous spiritual manifestations. Little by some of the leading figures of psychi- Emediums of all time. Whether or Sapia was only thirteen, but when the cal research of the day. not she really possessed psychic powers, family, enchanted by her gift, told her Although scientists were usually very she is a fascinating study in human psy- that she could stay as long as she contin- impressed by her, not all witnesses were chology. I will devote this and several ued to perform strange phenomena, she satisfied that the possibility of cheating future columns to her case. quickly resolved to please them. had been completely ruled out. When Born on January 21, 1854, in Miner- Her séances soon attracted the atten- sometimes she was caught cheating, vino Murge, a town in the province tion of many learned men, including the she would berate her investigators for of Bari in southern Italy, she was the eminent criminologist Cesare Lombroso failing to control her properly, pleading daughter of peasants and had little or that she could not be held responsible no formal education. Her mother died for what she might do while in a trance! soon after her birth, and her father was apparently killed by thieves when she The Sittings in Naples (1908) was twelve. In 1908 a very special series of sittings Neighbors arranged for her to con- took place in Naples under the auspices tact a native of the village who was of the Society for Psychical Research now living in Naples. -

The History Spiritualism

THE HISTORY of SPIRITUALISM by ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, M.D., LL.D. former President d'Honneur de la Fédération Spirite Internationale, President of the London Spiritualist Alliance, and President of the British College of Psychic Science Volume Two With Eight Plates Sir Arthur Conon Doyle CHAPTER I THE CAREER OF EUSAPIA PALLADINO The mediumship of Eusapia Palladino marks an important stage in the history of psychical research, because she was the first medium for physical phenomena to be examined by a large number of eminent men of science. The chief manifestations that occurred with her were the movement of objects without contact, the levitation of a table and other objects, the levitation of the medium, the appearance of materialized hands and faces, lights, and the playing of musical instruments without human contact. All these phenomena took place, as we have seen, at a much earlier date with the medium D. D. Home, but when Sir William Crookes invited his scientific brethren to come and examine them they declined. Now for the first time these strange facts were the subject of prolonged investigation by men of European reputation. Needless to say, these experimenters were at first sceptical in the highest degree, and so-called ‘tests’ (those often silly precautions which may defeat the very object aimed at) were the order of the day. No medium in the whole world has been more rigidly tested than this one, and since she was able to convince the vast majority of her sitters, it is clear that her mediumship was of no ordinary type. -

A Proj Ective Geometry for Separation Experiences

A Proj ective Geometry for Separation Experiences F. Gordon Greene Sacramento, CA ABSTRACT: I present a projective geometry for out-of-body "separation ex periences," built up out of a series of higher space analogies and resulting diagrams. The model draws upon recent understandings of cosmic symme tries linking relativity theory to quantum physics. This perspective is grounded inside a more general hyperspace theory, supposing that our three dimensional space is embedded within a hierarchy of higher dimensions. Only the next higher space, the fourth dimension, is directly utilized in this exposition. At least two degrees of consciousness expansion are identified as prerequisites to a comprehensive phenomenological taxonomy of ecstatic out of-body, near-death, and mystical/visionary experiences. The first assumes a partial spatiotemporalization of consciousness into a fractional domain lo cated between three and four dimensions. The second assumes a complete spatiotemporalization into four dimensions. Partial expansions are associated with separation experiences and with thematically related activities of a seeming paranormal character. Complete expansions are associated with "timeless" life panoramas and with excursions into hyperphysical realms. The paper concentrates on partial expansions, in analyzing the psychody namics underlying, and ostensive paranormal activities accompanying, sepa ration experiences. Higher space theories for ecstatic other world visions, and for re lated activities of a seeming paranormal character, have long in trigued parapsychologists. Among the ostensive psychic happenings so explained are such things as clairvoyance, remote viewing, telepathy, teleportation, psychokinesis (PK), psychic healing, levitation, and pre cognition (Broad, 1969; Dunne, 1927; Hinton, 1904; Krippner and Vil loldo, 1976; Lombroso, 1909; Luttenberger, 1977; Nash, 1963; F.