Deception by Subjects in Psi Research'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressive Cast of Thinkers and Performers

Table of Contents Long Synopsis Short Synopsis Michael Caplan Biography Key Production Personnel Filmography Credit List Magicians & Scholars Cover design by Lara Marsh, Illustration by Michael Pajon A Magical Vision /Long Synopsis ______________________________________________________ A Magical Vision spotlights Eugene Burger, a far-sighted philosopher and magician who is considered one of the great teachers of the magical arts. Eugene has spent twenty-five years speaking to magicians, academics, and the general public about the experience of magic. Advocating a return to magic’s shamanistic, healing traditions, Eugene’s “magic tricks” seek to evoke feelings of awe and transcendence, and surpass the Las Vegas-style entertainment so many of us visualize when we think of magicians. Mentors and colleagues have emerged throughout Eugene’s globe-trotting career. Among them is Jeff McBride, a recognized innovator of contemporary magic, and Max Maven, a one-man-show who performs a unique brand of “mind magic” to audiences worldwide. Lawrence Hass created the world’s first magic program in a liberal arts setting, where his seminar has attracted an impressive cast of thinkers and performers. The film, however, is Eugene’s journey. It began in 1940s Chicago, a city already renowned as the center of classic magic performance. Yale Divinity School followed, leading Eugene to the world of Asian mysticism. From there came the creation of Hauntings, a tribute to the sprit theatre of the 19th century, and the gore of the Bizarre Magick movement. Today Eugene’s performances and lectures draw inspiration from the mythology of India to the Buddhism of magical theory. On this stage, the magicians and thinkers open doors to an astounding world, a world that we rarely take time to see. -

March 6 Special Interest Groups DVR ALERT from DAVE

The SPIRIT | Official Newsletter of I.B.M. Ring 1 Meeting Update: March 6th M Arch 2 01 3 Special Interest Groups Volume 13, Issue 3 Inside this issue: The March 6 meeting program will feature “Special Interest Groups.” Three instructors will each simultaneously present 45 minute “hands on” teach-ins. Each instructor will only present 2 programs. You may select Meeting Update 1 any two of the three programs and when you have participated in your first program, you will then move on to your second program choice. DVR ALERT 1 Choices: Magic Past 2 Randy Kalin will present effective but simple card tricks with most being Ring Report 3-4 based on mathematical principles without difficult sleights. Schedule of Events 3 Mike Hindrichs, our close-up contest winner, will present his rope magic including routines and individual moves. Dues Info 4 Harry Monti will present the “Linking Rings.” He will demonstrate a Lecture Info 5 routine and then break it down and show the various elements. JDRF Info 6 These are “hands on” programs to be sure so bring your own cards, JDRF Photos 7 ropes and rings. Contest Winners 7 Harry Monti This Just In 8 NEW MEETING AGENDA 6:30 Magic 101 Quiet Please if you are not involved with Magic 101. 7:00 Refreshments/ Socialize and Jamming sessions 7:30 Special Interest Groups QUOTE: Following the meeting- Workshop and Fellowship till 10PM “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” DVR ALERT FROM DAVE Arthur C. Clarke, Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the David Copperfield posted this on Facebook- Possible “Breaking news! Excited to announce that I will be hosting magic on the Today Show EVERY Monday in March! It starts this Monday on NBC.” 2 From The Magic Past \ By Don Rataj Here is an update that I have listed in Magicpedia, however I am missing several years. -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

Historical Perspective

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 717–754, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Early Psychical Research Reference Works: Remarks on Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science Carlos S. Alvarado [email protected] Submitted March 11, 2020; Accepted July 5, 2020; Published December 15, 2020 DOI: 10.31275/20201785 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—Some early reference works about psychic phenomena have included bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and general over- view books. A particularly useful one, and the focus of the present article, is Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934). The encyclopedia has more than 900 alphabetically arranged entries. These cover such phenomena as apparitions, auras, automatic writing, clairvoyance, hauntings, materialization, poltergeists, premoni- tions, psychometry, and telepathy, but also mediums and psychics, re- searchers and writers, magazines and journals, organizations, theoretical ideas, and other topics. In addition to the content of this work, and some information about its author, it is argued that the Encyclopaedia is a good reference work for the study of developments from before 1933, even though it has some omissions and bibliographical problems. Keywords: Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science; Nandor Fodor; psychical re- search reference works; history of psychical research INTRODUCTION The work discussed in this article, Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934), is a unique compilation of information about psychical research and related topics up to around 1933. Widely used by writers interested in overviews of the literature, Fodor’s work is part of a reference literature developed over the years to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the early publications of the field by students of psychic phenomena. -

Counter Intelligence Is the Latest of a 36 Page Printed Booklet Which Do and It Is Completely Baffling, Release from the Brilliant Mind of Is Clear and Concise

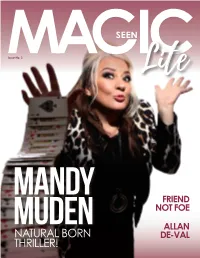

Issue No. 3 Lite MANDY FRIEND MUDEN NOT FOE ALLAN NATURAL BORN DE-VAL THRILLER! THE OPENER A WORD FROM THE EDITOR ow, we are into in Comedy Clubs after giving helps to fill us in on everything our third edition up her attempts to become an that is happening in this niche of Magicseen Lite actress, and although her rise entertainment world. already, yet it only has been steady rather than seems minutes meteoric, her good showing on What else have we extracted from sensible buying decisions. ago that we Britain’s Got Talent has helped the full September Magicseen If you enjoy this free taster edition Wdecided to go ahead with the to firmly established her act. We to include here? Well, there’s of Magicseen, maybe we can project at all! It’s great to see are delighted to provide further Friend Not Foe, which is an article tempt you to sign up for the that lots of readers are taking background on her for you to exploring how we can harness whole thing! We have 1 or 2 year advantage of these special enjoy in this issue. the ‘comedian’ in the audience printed copy or download subs taster issues and we hope to enhance our act rather than available, and subscribers not that you will enjoy this latest Escapology is an allied art to destroy it, we offer a Masterclass only get the full versions of every one too. magic that we rarely get to routine from David Regal’s brand issue 6 times a year, they also feature in Magicseen, so we are new book Interpreting Magic, we get other benefits too. -

Apport from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Apport From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia An apport is the paranormal transference of an article from one place to another, or an appearance of an article from an unknown source.[1] Apports are often associated with poltergeist activity, and on rare occasions are said to be witnessed landing on the floor, in a person's lap or dropping from the ceiling. Flowers are a well known form of apport at spiritualistic séances, but tar and mud have also been reported.[2] Conversely, an asport is the transference of a small object from a known location to an unknown location via paranormal means.[3] As with all paranormal phenomena, apports are highly controversial, with critics such as Robert Todd Carroll saying that they are the result of magic tricks.[4] [edit] References 1. ^ http://parapsych.org/historical_terms.html Historical Terms Glossary of the Parapsychological Association, entry on Apport, Retrieved Sept 6, 2007 2. ^ Fontana, David (2005). Is There an Afterlife: A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence. Hants, UK: O Books, 352-381. ISBN 1903816904. 3. ^ Kentucky Paranormal Research. Retrieved on 2007-09-19. "An asport is any object the spirits or the medium makes disappear or teleports to another location." 4. ^ http://www.skepdic.com/apport.html Apport entry in the Skeptic's Dictionary by Robert Todd Carroll, retrieved June 19, 2008 [edit] See also Teleportation Cosmic Gospel that UFO cults receive by psychic transmission from "Space Brothers Apports are 'gifts' that manifests from non-physical to physical reality. Manifestation may be linked to teleportation or telekinesis by one or more of the people in the room. -

The Salt City Magic Club August 2017

The Salt City Magic Club August 2017 This ’n’ That By B ruce Purdy What have you been up on it. working on this Summer? Whatever you’ve got, bring it Along with Bob Holland’s along to share with the group. “Close-Up” mini-lecture, we will have plenty of time to Are you having prob- “Session” together. Show us lems with a move, are develop- your latest projects. ing ideas for a new routine or Harris Solomon forgot how that old gizmo works Have you bought some or what it does? looking for A monthly newsletter of the new Magic? Been practicing a feedback on a routine? We stand Harris A. Solomon Ring #74 new card trick or sponge ball ready to help. International Brotherhood of Magicians routine? Maybe you pulled (the Salt City Magic Club) something out of your drawer I look forward to seeing President: Theresa Barniak that you haven’t used in a long you at the August meeting on Vice President: David Jackman time and have been brushing the 17th! Secretary: Ken Frehm Treasurer: Bruce Purdy Sgt. At Arms: David Hanselman Oops!! plied to my Facebook post that IBM Ring #74 meets at 7:30pm I realised - There NO meeting the Third Thursday of every month I showed up early for scheduled, as the 4th of July At Timber Tavern (See page 7 ) the meeting on 20th July. I picnic served as our “July meet- couldn’t understand why no one Please submit material for publication in the Wandogram to: ing”! else showed up until 7:30 when [email protected] the meeting was supposed to or by Snail Mail: D’oh! start. -

A Discussion of the Evidence That Personal Consciousness Persists After Death with Special Reference to Poltergeist Phenomena

pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Australian Journal of Parapsychology 2006, Volume 6, Number 1, pp. 5-20 A Discussion of the Evidence that Personal Consciousness Persists After Death with Special Reference to Poltergeist Phenomena WILLIAM ROLL Abstract: Humans have a dual mind, the mind of the left hemisphere and the mind of the right hemisphere. The left hemisphere has an organ for language and when awake can be conscious of things with linguistic labels. The right hemisphere is good at operating with mental images as in dreams. The functions of the right hemisphere include extrasensory perception and psychokinesis. However, the findings that have been advanced in favour of the idea that personality survives death have mostly been discussed in terms of the continuation of the left mind. This paper explores the pro and cons of this approach. THE TWO BRAIN HEMISPHERES AND THE IDEA OF SURVIVAL AFTER DEATH Following the lead of Frederic Myers (1903), the possibility of survival has been discussed in terms of the survival of personality, but with little attention to the organ where the idea of personality originates. Studies of the brain reveal that humans possess two very different personalities: the personality of the left-brain hemisphere and the personality of the right- brain hemisphere. Physiologically and psychologically each of us has a split personality. In the healthy individual the two sides of brain work together. In the simple act of walking, now it’s the right hemisphere and the left leg, then the left hemisphere and the right leg. -

The Underground Sessions Page 36

MAY 2013 TONY CHANG DAN WHITE DAN HAUSS ERIC JONES BEN TRAIN THE UNDERGROUND SESSIONS PAGE 36 CHRIS MAYHEW MAY 2013 - M-U-M Magazine 3 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan Proofreader & Copy Editor Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Publisher Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr. Parker, CO 80134 Copyright © 2012 Subscription is through membership in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues should be addressed to: Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134 [email protected] Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 Fax: 303-362-0424 Send assembly reports to: [email protected] For advertising information, reservations, and placement contact: Mona S. Morrison, M-U-M Advertising Manager 645 Darien Court, Hoffman Estates, IL 60169 Email: [email protected] Telephone/fax: (847) 519-9201 Editorial contributions and correspondence concerning all content and advertising should be addressed to the editor: Michael Close - Email: [email protected] Phone: 317-456-7234 Submissions for the magazine will only be accepted by email or fax. VISIT THE S.A.M. WEB SITE www.magicsam.com To access “Members Only” pages: Enter your Name and Membership number exactly as it appears on your membership card. 4 M-U-M Magazine - MAY 2013 M-U-M MAY 2013 MAGAZINE Volume 102 • Number 12 26 28 36 PAGE STORY 27 COVER S.A.M. NEWS 6 From -

Skeptical Inquirer the Condon UFO Study

the Skeptical Inquirer The Condon UFO Study Remote viewing Unmasked Flew on Parapsychology Sebeok on Animal Language Shneour on Occam's Razor VOL. X NO. 4 / SUMMER 1986 $5.00 Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John Boardman, John R. Cole, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Public Relations Andrea Szalanski (director), Barry Karr. Production Editor Betsy Offermann. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Systems Programmer Richard Seymour, Data-Base Manager Laurel Geise Smith. Typesetting Paul E. Loynes. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Staff Beth Gehrman, Ruthann Page, Alfreda Pidgeon, Laurie Van Amburgh. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher. State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Eduardo Amaldi, physicist. University of Rome, Italy. Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist, SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; John R. Cole, anthropologist. Institute for the Study of Human Issues; F. H. C. Crick, biophysicist, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, Calif; L. Sprague de Camp, author, engineer; Bernard Dixon, science writer, consultant; Paul Edwards, philos opher. -

Warsaw Pact (U)

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com ~--------------------------------------------- - ---------------------- DST-18108·303·78 PARAPHYSICS R&D-WARSAW PACT (U) ~ FEBRUARY 1980 l 1 RF.PAREO BY t:.S. AIR FOHCE AlR FORCE SYSTE MS COMMA:-.iD FOREIG~ TECHNOLOGY DI\'ISIO!'c N8'f RI3LBA8ABL:S 'i'8 F8RJ319~l ~ls'l'FI8l'JMS N6'f ftl3bEASABLJ3 'f8 C8N'i'lh'.z8~9R8 11itft!i llifl ? • 8:Pil'E 1.4 JEL£101" 4(.£ SOCitl!I.. I A .. CO ~ SI~TII~8.J l. fY8Js"WR llllllllllll ll'lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll "'21002 057 CI..Nlfted By. DWDT -~new 011. 1 October lJII DST-18108-202-78-Chg 1 4 February 1980 - PARAPHYSICS R&D-WARSAW PACT (U) ~(b)(3) 50 usc 3024(i);(b)(6) Authors: ~ DST-18108-202-78 DIA TASK NO. PT-1810.18-78 DATE OF PUBLICATION 80 MARCH 1978 Information Cutoff Date 1 October 1979 - This is a Department of Defenee Intelligence Document prepared by the Foreign Technology Diviaion, Air Force Systems Command and approved by Asaiatant Vice Directorate for Science and Technology Intelligence of the Defense Intelligence Agency. This doument has been processed for CIRC l'fJ!IftlfHf8 lt6'f'lel!l l!f'fl!lbt:I81!lfiBI!l S8tiftel!l8 1\ifB Mii'PH8BS Jti'\'81NBD NO I ftZI:f!l\'8dfi!J 'f6 P6Mll8fi ffh'fl8ffllrZ8 NUl KELEAI!KBUJ 'f8 S8PilRI/.zQ'I'9RI!J Clasollled By: DIA/DT (Reverse Blank) Review on 1 October 11191 - llil~iU~'f (This page is Unclassified) UNCLASSIFIED DST-18108-202-78 - 30 March 1978 "I did the best I could, let those who can do better." L. -

The Responsibilities of the Media and Paranormal Claims

The Responsibilities of the Media and Paranormal Claims Because the media are a dominant influence in the growth of belief in the paranormal, there is a need to develop among journalists an appreciation for critical judgment in evaluating claims of truth. Paul Kurtz HE COMMITTEE FOR the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal was founded when a number of scientific skeptics Tand rationalists, increasingly concerned about the rising tide of unchallenged paranormal claims, decided to form a coalition of individuals committed to the use of science and rational methods of inquiry in evalu ating such claims. The word paranormal was being loosely used (we did not invent the term) to include many diverse things under its rubric; everything from psychic prophecies, ESP, clairvoyance, telepathy, psychokinesis, appari tions, hauntings, poltergeists, communication with discarnate spirits, rein carnation, levitation, psychic healings, on the one hand, to astrological charts and horoscopes, UFO sightings and abductions, Bermuda Triangles, and monsters of the deep, on the other. We thought it incredible that so many films, TV and radio programs, news stories, and books were pre senting these paranormal claims as the gospel truth, even maintaining that they had been proven by science, and that there was little or no public awareness of the fact that when these claims were subjected to careful scientific appraisal they were shown to be either unverified or false. We found the paranormal field so rife with wishful and exaggerated claims that we felt the public should have the opportunity to learn about dissenting scientific studies and thus have a more balanced picture.